1918 Irish general election

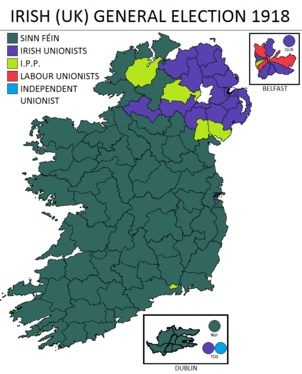

The Irish general election of 1918 was that part of the 1918 United Kingdom general election which took place in Ireland. It is now seen as a key moment in modern Irish history because it saw the overwhelming defeat of the moderate nationalist Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP), which had dominated the Irish political landscape since the 1880s, and a landslide victory for the radical Sinn Féin party. It had never stood in a general election, but had won six seats in by-elections in 1917–18. Sinn Féin had vowed in its manifesto to establish an independent Irish Republic. In Ulster, however, the Unionist Party was the most successful party.

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1918 United Kingdom general election (Ireland) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

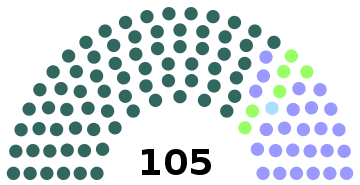

105 of the 707 seats to the House of Commons of the United Kingdom | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1918 Irish general election | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All 105 seats in Dáil Éireann 53 seats were needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Results of the 1918 election in Ireland. Sinn Féin MPs refused to sit in the House of Commons and instead formed Dáil Éireann. The Irish Parliamentary Party, Irish Unionist Alliance, Labour Unionist Party and an Independent Unionist MP remained in Westminster. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The election was held in the aftermath of the First World War, the Easter Rising and the Conscription Crisis. It was the first general election to be held after the Representation of the People Act 1918. It was thus the first election in which women over the age of 30, and all men over the age of 21, could vote. Previously, all women and most working-class men had been excluded from voting.

In the aftermath of the elections, Sinn Féin's elected members refused to attend the British Parliament in Westminster (London), and instead formed a parliament in Dublin, the First Dáil Éireann ("Assembly of Ireland"), which declared Irish independence as a republic. The Irish War of Independence was conducted under this revolutionary government which sought international recognition, and set about the process of state-building.[1][2]

Background

In 1918 the whole of Ireland was a part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and was represented in the British Parliament by 105 MPs. Whereas in Great Britain most elected politicians were members of either the Liberal Party or the Conservative Party, from the early 1880s most Irish MPs were Irish nationalists, who sat together in the British House of Commons as the Irish Parliamentary Party.

The IPP strove for Home Rule, that is, limited self-government for Ireland within the United Kingdom, and had been supported by most Irish people, especially the Catholic majority. Home Rule was opposed by most Protestants in Ireland, who formed a majority of the population in parts of the northern province of Ulster but a minority in the rest of Ireland, and favoured maintenance of the Union with Great Britain (and were therefore called Unionists).

The Unionists were supported by the Conservative Party, whereas from 1885 the Liberal Party was committed to enacting some form of Home Rule. Unionists eventually formed their own representation, first the Irish Unionist Party then the Ulster Unionist Party. Home Rule appeared to have been finally achieved with the passing of the Home Rule Act 1914. However, the implementation of the Act was temporarily postponed with the outbreak of World War I due to determined Ulster Unionists' resistance to the Act. As the war prolonged and with the failure to make any progress on the issue, the more radical Sinn Féin began to grow in strength.

Rise of Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin was founded by Arthur Griffith in 1905. He believed that Irish nationalists should emulate the Ausgleich of Hungarian nationalists who, in the 19th century under Ferenc Deák, had chosen to boycott the imperial parliament in Vienna and unilaterally established their own legislature in Budapest.

Griffith had favoured a peaceful solution based on 'dual monarchy' with Britain, that is two separate states with a single head of state and a limited central government to control matters of common concern only. However, by 1918, under its new leader Éamon de Valera, Sinn Féin had come to favour achieving separation from Britain by means of an armed uprising if necessary and the establishment of an independent republic.

In the aftermath of the 1916 Easter Rising the party's ranks were swelled by participants and supporters of the rebellion as they were freed from British gaols and internment camps, and at its 1917 Ard Fheis (annual conference) de Valera was elected leader and the new, more radical policy adopted.

Prior to 1916, Sinn Féin had been a fringe movement having a limited cooperative alliance with William O'Brien's All-for-Ireland League and enjoyed little electoral success. However, between the Easter Rising of that year and the 1918 general election, the party's popularity increased dramatically. This was due to the failure to have the Home Rule Bill implemented when the IPP resisted the partition of Ireland demanded by Ulster Unionists in 1914, 1916 and 1917, but also popular antagonism towards the British authorities created by the execution of most of the leaders of the 1916 rebels and by their botched attempt to introduce Home Rule on the conclusion of the Irish Convention linked with military conscription in Ireland (see Conscription Crisis of 1918).

Sinn Féin demonstrated its new electoral capability in four by-election successes in 1917 in which Count Plunkett, Joseph McGuinness, de Valera and W. T. Cosgrave were each elected, although it lost three by-elections in early 1918 before winning two more with Patrick McCartan and Arthur Griffith. In one case there were unproven allegations of electoral fraud.[3] The party had benefitted from a number of factors in the 1918 elections, including demographic changes and political factors.

Changes in the electorate

The Irish electorate in 1918, as with the entire electorate throughout the United Kingdom, had changed in two major ways since the preceding general election. Firstly, there was a "generational" change because of the First World War, which meant that the British general election due in 1915 had not taken place. As a result, no election took place between 1910 and 1918, the longest gap in modern British and Irish constitutional history until then (it was superseded in Britain in 1935–45). Thus the 1918 election saw, in particular:

- All voters between the age of 21 and 29 were first time general election voters. They had no history of past voter loyalty to the IPP to fall back on, and had begun their political awareness in the period of 8 years that had seen a bitter world war, the home rule controversy and the Easter Rising and its aftermath.

- A generation of older voters, most of them IPP supporters, had died in that eight-year period.

- Emigration (except to Britain) had been almost impossible during the war because of the dangerous sea lanes, which meant that tens of thousands of young people were in Ireland who in normal times would have been abroad.

- As Ireland had not had conscription, Unionists and moderate Nationalists had predominantly made up the volunteers for the duration of the war. Consequently, there was a large loss in the age range of young Unionists and moderate Nationalists, which did not occur amongst Republicans who had not volunteered.

Secondly, the franchise had been greatly extended by the Representation of the People Act 1918. This granted voting rights to women (albeit only those over 30) for the first time, and gave all men over 21 and military servicemen over 19 a vote in parliamentary elections without property qualifications. The Irish electorate increased from around 700,000 to about two million.[4]

Overall, a new generation of young voters, and the sudden influx of women over thirty, meant that vast numbers of new voters of unknown voter affiliation existed, changing dramatically the make-up of the Irish electorate.

Political factors

- Since the previous general election in December 1910, the formerly-dominant Irish Parliamentary Party, unchallenged for nearly a decade, was largely of an older generation. Its local organisation had atrophied, making defence of its seats difficult. The party's votes in parliament had been decisive in passing the 1914 Home Rule Act but, due to the outbreak of the War, it was never put into effect. The party's policy was to achieve All-Ireland self-government constitutionally, within the framework of the United Kingdom, as opposed to using separatist physical force.

- The electorate had become enamoured with Sinn Féin, particularly due to the harsh response of the authorities to the Easter Rising. Sinn Féin had been falsely blamed for the Rising even though it had taken no part in it. The party also took most of the credit for the successful campaign to prevent the introduction of conscription in 1918.

- Whereas the IPP had conceded a temporary form of partition in 1914, as a measure to pacify Ulster loyalists, Sinn Féin felt that that would worsen and prolong any differences between north and south.

- In contrast to the IPP, Sinn Féin were seen as a young and radical force. Its leaders, such as Michael Collins (28) and de Valera (36), were young militant politicians, like most of the new voters and their imprisoned republican candidates.

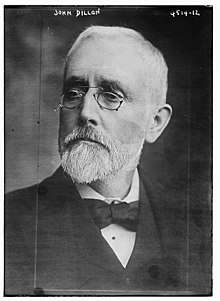

- IPP leaders such as John Dillon, who had been in public office since the 1880s, were largely older, moderate politicians, and had campaigned for All-Ireland Home Rule since the time of Charles Stewart Parnell, and continued to press for the implementation of the 1914 Act, and a constitutional solution to have Ulster included in the jurisdiction of a Dublin parliament.

- On the other hand, Sinn Féin promoted a radical new policy of achieving Irish self-government outside of the UK, and many of its volunteer wing were ready to defend a republic with physical force. By 1918, Sinn Féin followers had come to see the gradual acquisition of All-Ireland Home Rule as an idea whose time had come and gone.

- The Irish population had been radicalised during World War I. In addition to the heavy losses suffered by Irish regiments, the conscription threat and British military measures, there was rapid inflation that sparked off a wave of strikes and industrial disputes. The 1918 election also occurred at a time of revolution across Europe.

- Unionist fear of Home Rule, or worse, separation, solidified after the Rising, and the Unionist vote was enhanced in Ulster by the increased electorate. It was the first election since the Ulster Covenant, the formation of the Ulster Volunteers (UVF), and the Battle of the Somme.

- Sinn Féin's policy was outlined in its election manifesto, which aimed for Irish representation at any post-war peace conference. By contrast, IPP policy was to leave negotiation to the British government.

- Nearly a year earlier, in January 1918, Woodrow Wilson had issued his Fourteen Points policy, which seemed to promise that self-government and self-determination would become the norm in international relations.

- The Ulster Unionists' resistance to All-Ireland self-government remained unresolved, and little account was taken of Unionist reservations about what they contended would be Catholic rule from Dublin.

The election

Voting in most Irish constituencies occurred on 14 December 1918. While the rest of the United Kingdom fought the 'Khaki election' on other issues involving the British parties, in Ireland four major political parties had national appeal. These were the IPP, Sinn Féin, the Irish Unionist Party and the Irish Labour Party. The Labour Party, however, decided not to participate in the election, fearing that it would be caught in the political crossfire between the IPP and Sinn Féin; it thought it better to let the people make up their minds on the issue of Home Rule versus a Republic by having a clear two-way choice between the two nationalist parties. The Unionist Party favoured continuance of the union with Britain (along with its subordinate, the Ulster Unionist Labour Association, who fought as 'Labour Unionists'). A number of other small nationalist parties also took part.

In Ireland 105 MPs could be elected from 103 constituencies (although, as stated below, four MPs were elected for two constituencies and so the total number of people elected was 101). Ninety-nine seats were elected from single seat geographical constituencies under the first-past-the-post voting system. However, there were also two two-seat constituencies: University of Dublin (Trinity College) elected two MPs under the single transferable vote and Cork City elected two MPs under the bloc voting system.

In addition to ordinary geographical constituencies there were three university constituencies: the Queen's University of Belfast (which returned a Unionist), the University of Dublin (which returned two Unionists) and the National University of Ireland (which returned a member of Sinn Féin).

Of the 105 seats, 25 were uncontested, with a Sinn Féin candidate winning unopposed. Seventeen of these seats were in Munster. In some cases it was because there was a certain winner in Sinn Féin. British government propaganda formulated in Dublin Castle and circulated through a censored press alleged that republican militants had threatened potential candidates to discourage non-Sinn Féiners from running.

Results

Voting summary

| Summary of 14 December 1918 Dáil Éireann and House of Commons election results | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

| Party |

Leader |

Votes |

% Votes |

Swing% |

TDs/MPs |

Change (since Dec. 1910) |

% of seats | |||||

| Sinn Féin[nb 1] | Éamon de Valera | 476,087 | 46.9 | 73 | 69.5 | |||||||

| Irish Unionist | Edward Carson | 257,314 | 25.3 | 22 | 20.9 | |||||||

| Irish Parliamentary | John Dillon | 220,837 | 21.7 | 6 | 5.7 | |||||||

| Labour Unionist | None | 30,304 | 3.0 | 3 | 2.8 | |||||||

| Belfast Labour | None | 12,164 | 1.2 | 0 | 0 | |||||||

| Independent Unionist | —[nb 2] | 9,531 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.95 | |||||||

| Independent Nationalist | — | 8,183 | 0.8 | N/A | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Independent Labour | — | 659 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | |||||||

| Independent | — | 436 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | |||||||

| Total | 1,015,515 | 100 | 105 | |||||||||

Seats summary

Analysis

Sinn Féin candidates won 73 seats out of 105, but four party candidates (Arthur Griffith, Éamon de Valera, Eoin MacNeill and Liam Mellows) were elected for two constituencies and so the total number of individual Sinn Féin MPs elected was 69. Despite the isolated allegations of intimidation and electoral fraud on the part of both republicans and unionists, the election was seen as a landslide victory for Sinn Féin.

Sinn Féin received 46.9% of votes island-wide, and 65% of votes in the area that became the Irish Free State.[5] However, the 46.9% is not the total result of the overall success of Sinn Féin. That figure only accounts for 48 seats that they won because in 25 of the other constituencies the other parties did not contest them, and Sinn Féin won them unopposed. Most of these constituencies were Sinn Féin strongholds. It is estimated that, had the 25 seats been contested, Sinn Féin would have received at least 53% of the vote island-wide.[6] However, this is a conservative estimate and the percentage would likely have been higher.[6] Sinn Féin also did not contest four seats due to a deal with the IPP (see below). Labour, who had pulled out in the south under instructions to 'wait', polled better in Belfast than Sinn Féin.[7] Within the 26 counties that became the Irish Free State, Sinn Féin achieved 400,269 votes in the contested seats out of 606,117 total votes cast which amounted to a huge landslide of 66.0% in the vote and winning 70 out of the 75 constituencies.

The Irish Unionist Party won 22 seats and 25.3% of the vote island-wide (29.2% when Labour Unionist candidates are included), becoming the second-largest party in terms of MPs. The success of the unionists, who won 26 seats overall,[8] was largely limited to Ulster. Otherwise, southern unionists were elected only in the constituencies of Rathmines and the University of Dublin which returned two. In the 26 counties that later became the Irish Free State and then the Republic of Ireland, the Irish Unionist Alliance polled 37,218 votes from 101,839 total votes cast for other parties in the constituencies that they stood a candidate. However, if all of the total votes in the contested seats where the Irish Unionist Alliance did not stand are included there was a total of 606,117 votes cast, which converts the Irish Unionist Alliance share of the vote in the 26 counties to just 6.1%. With the one Independent Unionist being elected for Dublin University adding 0.1% in total with 793 votes to give 6.2% across the 26 counties and only 3 seats won by the Unionists.

The IPP suffered a catastrophic defeat and even its leader, John Dillon, was not re-elected. It won only six seats in Ireland, its losses exaggerated by the "first-past-the-post" system which gave it a share of seats far short of its much larger share of the vote (21.7%) and the number of seats it would have won under a "proportional representation" ballot system. All but one of its seats were in Ulster. The exception was Waterford City, the seat previously held by John Redmond, who had died earlier in the year, and retained by his son Captain William Redmond. Four of their Ulster seats were part of the deal to avoid unionist victories which saved some for the party but may have cost it the support of Protestant voters elsewhere. The IPP came close to winning other seats in Louth and Wexford South, and in general their support held up better in the north and east of the island. The party was represented in Westminster by seven MPs because T. P. O'Connor won the Liverpool Scotland seat due to Irish emigrant votes. The remnants of the IPP in time became the Nationalist Party under the leadership of Joseph Devlin. In the 26 counties that became the Irish Free State, the Irish Parliamentary Party won 181,320 votes out of 606,117 total votes cast in the contested seats which amounts to a 26.0% vote share. If the Independent Home Rule Nationalists are included there were 11,162 votes which comes to 1.8% and a vote share of 27.8% for the Nationalists. The Irish Parliamentary Party held on to just 2 seats in the 26 counties that became Southern Ireland and then the Irish Free State.

Ulster

In Ulster (nine-counties), Unionists won 23 out of the 38 seats with Sinn Féin gaining ten and the Irish Parliamentary Party five. There was a limited electoral pact brokered by Roman Catholic Cardinal Michael Logue in December between Sinn Féin and the Nationalist IPP in eight seats. However, it only concluded after nominations closed. Sinn Féin, remarkably successfully, instructed its supporters to vote IPP in Armagh South, despite no Unionist candidate (79 SF votes), Down South (33 SF votes for Éamon de Valera), Tyrone North-East (56 SF votes) and Donegal East (46 SF votes).

The IPP instructed its supporters to vote Sinn Féin in Fermanagh South (132 IPP votes) which had no Unionist candidate, Londonderry City (120 IPP votes) where Eoin MacNeill narrowly beat the Unionist, and Tyrone North-West also against a Unionist but where no IPP candidate was nominated.

The discipline of voters, when faced with two rival nationalist candidates and with only a post-nomination pact, was impressive. The pact only broke down in Down East where a Unionist won as the IPP candidate refused to participate, thus splitting the Catholic nationalist vote.

There was no pact in Belfast Falls which Joe Devlin (IPP) won with 8,488 votes against 3,245 for Éamon de Valera (SF) although no Unionist stood. The only other Belfast seat contested by both nationalist parties was Duncairn against Edward Carson, otherwise Sinn Féin stood alone in seven seats reaching double figures in two. Monaghan North was won by Sinn Féin's Ernest Blythe in a three-cornered fight against both IPP and Unionist candidates.

In the Monaghan South, and Donegal North, South and West seats, despite no Unionist standing, Sinn Féin won all four against IPP candidates.

Sinn Féin took the two (uncontested) Cavan seats with Arthur Griffith taking his second in Cavan East as well as that of Tyrone North West.

In six contested seats no Unionist stood.

Unionists won a clear majority of the 38 Ulster seats including eight of the nine in Belfast. In the six Ulster counties which formed the future Northern Ireland, Unionists won 23 of the 30 seats. The vote totals were:[9]

| Party |

Votes |

% Votes |

Seats |

% Seats | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irish Unionist | 225,082 | 56.2 | 20 | 69.0 | |

| Sinn Féin | 76,100 | 19.0 | 3 | 6.9 | |

| Irish Parliamentary | 44,238 | 11.1 | 4 | 13.8 | |

| Labour Unionist | 30,304 | 7.6 | 3 | 10.3 | |

| Belfast Labour | 12,164 | 3.0 | 0 | — | |

| Independent Unionist | 8,738 | 2.2 | 0 | — | |

| Independent Nationalist | 2,602 | 0.6 | 0 | — | |

| Independent Labour | 659 | 0.2 | 0 | — | |

| Independent | 436 | 0.1 | 0 | — | |

| Total | 400,323 | 30 | |||

Aftermath and legacy

On 21 January 1919, 27 (out of 101 elected) members representing thirty constituencies answered the roll of Dáil Éireann—the Irish for "Assembly of Ireland". Invitations to attend the Dáil had been sent to all 100 men and one woman who had been elected on 14 December 1918. Eoin MacNeill had been elected for both Londonderry City and the National University of Ireland. Thirty-three republicans were unable to attend as they were in prison, most of them without trial since 17 May 1918. Pierce McCan (of Tipperary East), who died in prison, would have brought the total to thirty-four. Of the 69 republicans elected, most had fought in the Easter Rising.[10]

In accordance with the Sinn Féin manifesto, their elected members refused to attend Westminster, having instead formed their own parliament. Dáil Éireann was, according to John Patrick McCarthy, the revolutionary government under which the Irish War of Independence was fought and which sought international recognition.[1] Maryann Gialanella Valiulis says that having justified its existence, the Dáil provided itself with a theoretical framework and set about the process of state-building.[2]

After having dominated Irish politics for four decades, the IPP was so decimated by its massive defeat that it dissolved soon after the election. As mentioned above, its remains became the Northern Ireland-based Nationalist Party, which survived in Northern Ireland until 1969.

The British administration and unionists refused to recognise the Dáil. At its first meeting attended by 27 deputies (other were still imprisoned or impaired) on 21 January 1919 the Dáil issued a Declaration of Independence and proclaimed itself the parliament of a new state, the Irish Republic.

On the same day, in unconnected circumstances, two members of the Royal Irish Constabulary guarding gelignite were killed in the Soloheadbeg Ambush by members of the Irish Volunteers. Although it had not ordered this incident, the course of events soon drove the Dáil to recognise the Volunteers as the army of the Irish Republic and the ambush as an act of war against Great Britain. The Volunteers therefore changed their name, in August, to the Irish Republican Army. In this way the 1918 elections led to the outbreak of the Anglo-Irish War, giving the impression that the election sanctioned the war.

The train of events set in motion by the elections would eventually bring about the creation of the Irish Free State as a British dominion in 1922. That state became the first internationally recognised independent Irish state in 1931, when the Statute of Westminster removed virtually all of the UK Parliament's remaining authority over the Free State and the other dominions. The Free State eventually evolved into the modern Republic of Ireland. The leaders of the Sinn Féin candidates elected in 1918, such as de Valera, Michael Collins and W. T. Cosgrave, came to dominate Irish politics. De Valera, for example, would hold some form of elected office from his first election as an MP in a by-election in 1917 until 1973. The two major parties in the Republic of Ireland today, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, are both descendants of Sinn Féin, which first enjoyed substantial electoral success in 1918.

Prominent candidates

Elected unopposed

| Name | Party | Constituency |

|---|---|---|

| Arthur Griffith | Sinn Féin | Cavan East and also Tyrone North West (contest) |

| Éamon de Valera | Sinn Féin | Clare East and also Mayo East (contest) |

| Terence MacSwiney | Sinn Féin | Cork Mid |

| Michael Collins | Sinn Féin | Cork South |

| Seán Hayes | Sinn Féin | Cork West |

| Liam Mellows | Sinn Féin | Galway East and also Meath North (contest) |

| Piaras Béaslaí | Sinn Féin | Kerry East |

| Austin Stack | Sinn Féin | Kerry West |

| W. T. Cosgrave | Sinn Féin | Kilkenny North |

| Patrick McCartan | Sinn Féin | King's County[11] |

| Count Plunkett | Sinn Féin | Roscommon North |

Elected in contests

Defeated

| Name | Party | Constituency |

|---|---|---|

| John Dillon | Irish Parliamentary Party | Mayo East |

See also

Footnotes

- McCarthy, John Patrick (2006). Ireland: A Reference Guide from the Renaissance to the Present. Infobase Publishing. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-8160-5378-0.

- Valiulis, Maryann Gialanella (1992). Portrait of a revolutionary: General Richard Mulcahy and the founding of the Irish Free State. University Press of Kentucky. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-8131-1791-1.

- On one occasion the 'victory' of a Sinn Féin candidate in the Longford by-election is said to have been achieved through putting a gun to the head of a returning officer and telling him to "think again" when he was about to announce an IPP victory. On doing a 'recheck' the official 'found' new uncounted ballot papers in which votes were cast for the Sinn Féin candidate. Tim Pat Coogan, Michael Collins: A Biography (Hutchinson, 1990) p.67.

- Alvin Jackson, Ireland 1798-1998: War, Peace and Beyond, John Wiley & Sons, 2010, p. 210. ISBN 1444324152.

- Knirck, Jason K. Imagining Ireland's Independence: The Debates Over the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921. Rowman & Littlefield, 2006. p.45

- The Irish Election of 1918. ARK. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- The Resurrection of Ireland: The Sinn Féin Party, 1916-1923, Michael Laffan

- The Resurrection of Ireland: The Sinn Féin Party, 1916-1923, Michael Laffan p. 164

- http://www.ark.ac.uk/elections/h1918.htm

- Comerford, Maire (1969). The First Dáil. Joe Clarke. p. 11.

- King's County is now known as County Offaly.

- Queen's County is now known as County Laois (old spelling, 'Leix').

Notes on election results

- The percentage of votes given is a percentage of the total number of votes cast and therefore does not take into account the preferences of voters in constituencies where no contest occurred because of the overwhelming support for Sinn Féin there. It is impossible to know with certainty what the final shares of votes cast might have been had all constituencies been contested.

- Elected independent unionist candidate was Robert Henry Woods.

References

- Tim Pat Coogan, Michael Collins

- John Patrick McCarthy, Ireland: A Reference Guide from the Renaissance to the Present

- Maryann Gialanella Valiulis, Portrait of a revolutionary: General Richard Mulcahy and the founding of the Irish Free State

- Michael Laffan, The Resurrection of Ireland: The Sinn Féin Party, 1916-1923

- Maire Comerford, The First Dáil

- Dorothy Macardle, The Irish Republic (book)