Irish Citizen Army

The Irish Citizen Army (Irish: Arm Cathartha na hÉireann), or ICA, was a small paramilitary group of trained trade union volunteers from the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union (ITGWU) established in Dublin for the defence of workers' demonstrations from the Dublin Metropolitan Police. It was formed by James Larkin, James Connolly and Jack White on 23 November 1913.[1] Other prominent members included Seán O'Casey, Constance Markievicz, Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, P. T. Daly and Kit Poole. In 1916, it took part in the Easter Rising, an armed insurrection aimed at ending British rule in Ireland.[2] Despite the relatively small size of the army, it was more organised than the larger Irish Volunteers, with its members receiving superior training and being less affected by factional and ideological division.[3] The ICA became involved in the War of Independence, taking responsibility for parts of Dublin and aiding the Irish Republican Army in various operations.

| Irish Citizen Army | |

|---|---|

Arm Cathartha na hÉireann Participant in | |

Irish Citizen Army group outside ICA HQ Liberty Hall under a banner which reads "We serve neither King nor Kaiser but Ireland" | |

| Active | 1913–1947 |

| Ideology | Irish republicanism Socialism Marxism Anti-imperialism |

| Leaders |

|

| Headquarters | Liberty Hall, Dublin |

| Size | 1,000+ (1913) c.300 (1916) |

| Allies | |

| Opponent(s) | British Army Royal Irish Constabulary Dublin Metropolitan Police Industrialists |

| Battles and war(s) |

|

The Lockout of 1913

The Citizen Army arose out of the great strike of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU) in 1913, known as the Lockout of 1913. The dispute was over the recognition of that labour union, founded by James Larkin. It began when William Martin Murphy, an industrialist, locked out some trade unionists on 19 August 1913. On 25 August, in response, Larkin called an all-out tramway strike on Murphy's Dublin United Tramway Company. Other companies, encouraged by Murphy, sacked ITGWU members in an effort to break the union. The conflict eventually escalated to involve 400 employers and 25,000 workers. "Larkinism" prompted the recruitment of a workers' militia. However, Larkin was arrested by strikebreakers in October; James Connolly, his deputy, took control for the duration of the lockout, announcing a call to arms of four battalions of trained men with corporals and sergeants.

This strike caused most of Dublin to come to an economic standstill; it was marked by vicious rioting between the strikers and the Dublin Metropolitan Police, particularly at a rally on O'Connell Street on 31 August, in which two men were beaten to death and about 500 more injured. Another striker was later fatally wounded by a ricochet from a revolver fired by a strike-breaker.[4] The violence at union rallies during the strike prompted Larkin to call for a workers' militia to be formed to protect themselves against the police. The Citizen Army for the duration of the lock-out was armed with hurleys (sticks used in hurling, a traditional Irish sport) and bats to protect workers' demonstrations from the police. Jack White, a former Captain in the British Army, volunteered to train this army and offered £50 towards the cost of shoes to workers so that they could train. In addition to its role as a self-defence organisation, the Army, which was drilled in Croydon Park in Fairview by White, provided a diversion for workers unemployed and idle during the dispute. After a six-month standoff, the workers returned to work hungry and defeated in January 1914. The original purpose of the ICA was over, but it would soon be totally transformed.

Re-organisation

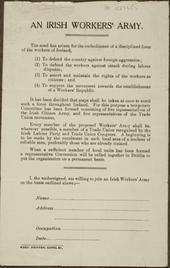

The Irish Citizen Army underwent a complete reorganisation in 1914.[5] In March of that year, police attacked a demonstration of the Citizen Army and arrested Jack White, its commander. Seán O'Casey, the playwright, then suggested that the ICA needed a more formal organisation. He wrote a constitution, stating the Army's principles as follows: "the ownership of Ireland, moral and material, is vested of right in the people of Ireland" and to "sink all difference of birth property and creed under the common name of the Irish people".[5]

Larkin insisted that all members also be members of a trade union, if eligible. In mid-1914, White resigned as ICA commander in order to join the mainstream nationalist Irish Volunteers, and Larkin assumed direct command.

The ICA armed itself with Mauser rifles, bought from Germany by the Irish Volunteers and smuggled into Ireland at Howth in July 1914. This organisation was one of the first to offer equal membership to both men and women, and trained them both in the use of weapons. The army's headquarters was the ITGWU union building, Liberty Hall, and membership was almost entirely Dublin-based. However, Connolly also set up branches in Tralee and Killarney in County Kerry. Tom Clarke called a meeting of all the separatist groups in Dublin on 9 September 1914 to assist a German invasion of Ireland, and prevent the police disarming the Volunteers.[6] An intellectual dispute broke out within the ranks of the ICA between Liam O'Briain and the ICA's military commander, Michael Mallin, who thought that the former's plan for an integrated movement was totally unrealistic. O'Briain wanted to pursue a strategy without the Dublin brigade being "cooped up in the city". Mallin told him that, on the contrary, the whole strategy was to focus on the central objective on and around Dublin Castle. Little did they know that the Castle and the barracks behind possessed no more than a skeleton garrison, and could have been taken by a token force.[6]

James Larkin left Ireland for America in October 1914, leaving the Citizen Army under the command of James Connolly. Whereas during the Lockout the ICA had been a workers' self-defence militia, Connolly conceived of it as a revolutionary organisation dedicated to the creation of an Irish socialist republic. He had served in the British Army in his youth, and knew something about military tactics and discipline. Other active members in the early days included the Secretary to the Council, Seán O'Casey, who tried to have Constance Markievicz expelled for her close associations with the Volunteers, which he considered as being "inimical" to the ICA's best interests. Francis Sheehy-Skeffington and O'Casey left the ICA when it became apparent that Connolly had started gravitating towards the radical nationalist group, the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). The ICA was grossly under-funded. John Devoy, the prominent Irish-American member of IRB Fenians, believed the existence of "a land army on Irish soil" was the most important sign since the founding of the Gaelic League.[7] James Connolly, a convinced Marxist socialist and Irish Republican, believed that achieving political change through physical force, in the tradition of the Fenians, was legitimate. The ICA was the victim of small numbers, that shrank to only 200-300 persons, and fitful discipline.[8]

In October 1915, armed ICA pickets patrolled a strike by dockers at Dublin port. Appalled by the participation of Irishmen in the First World War, which he regarded as an imperialist, capitalist conflict, Connolly began openly calling for insurrection in his newspaper, the Irish Worker. When this was banned he opened another, the Worker's Republic.

An armed organisation of the Irish working class is a phenomenon in Ireland. Hitherto the workers of Ireland have fought as parts of the armies led by their masters, never as a member of any army officered, trained and inspired by men of their own class. Now, with arms in their hands, they propose to steer their own course, to carve their own future.

— James Connolly, Workers' Republic, 30 October 1915

British authorities tolerated the open drilling and bearing of arms by the ICA, thinking that to clamp down on the organisation would provoke further unrest. A small group of IRB conspirators within the Irish Volunteers movement had started planning a rising. Worried that Connolly would embark on premature military action with the ICA, they approached him and inducted him into the IRB's Supreme Council to co-ordinate their preparations for the armed rebellion which became known as the Easter Rising.

Easter Rising

.svg.png)

On Monday, 24 April 1916, 220 members of the ICA (including 28 women) took part in the Easter Rising, alongside a much larger body of the Irish Volunteers. They helped occupy the General Post Office (GPO) on O'Connell Street (then named Sackville Street), Dublin's main thoroughfare. Michael Mallin, Connolly's second-in-command, along with Kit Poole, Constance Markievicz and an ICA company, occupied St Stephen's Green.[9] Another company under Sean Connolly took over City Hall and attacked Dublin Castle. Finally, a detachment occupied Harcourt Street railway station. ICA men were the first rebel casualties of Easter week, two of them being killed in an abortive attack on Dublin Castle. The confusion in the chain of command caused conflict with the Volunteers. Harry Colley and Harry Boland came out from their outposts in the Wicklow Chemical Manure Company's office 200 yards away, where they were under the command of an irascible officer, Vincent Poole; the post had been set up by James Connolly, without countermanding orders from affective Volunteers.[10]

Sean Connolly, an ICA officer and Abbey Theatre actor, was both the first rebel to kill a British soldier and the first to be killed.[11]

A total of eleven Citizen Army men were killed in action in the rising, five in the City Hall/Dublin castle area, five in St Stephen's Green and one in the GPO.

James Connolly was made commander of the rebel forces in Dublin during the Rising, and issued orders to surrender after a week. He and Mallin were executed by British Army firing squad some weeks later. The surviving ICA members were interned, in English prisons or at Frongoch internment camp in Wales, for between nine and 12 months.

Operations post Easter Rising

Many of the ICA later joined the new Irish Republican Army (IRA) at various times. However the Citizen Army under Connolly's elected successor, chief Rising bomb-maker and builder James O'Neill, became involved in War of Independence. During this time the ICA were active in County Dublin – two miles either side of the River Liffey and into Kildare as far as Maynooth. The war ended in the Treaty of 1921, which would establish 26 of the 32 Irish counties as the Irish Free State in December 1922. With their small numbers the ICA were unable to take a leading role in the war, however they developed a connection with the Irish Republican Army, and some members of the ICA helped to produce and distribute IRA propaganda, conducted "detective work" on their behalf, provided medical support for the Republican forces and supplied them with weapons. ICA director of munitions Séamas McGowan secured rifles through contacts in the British Army.[12] O'Neill was also joint intelligence and logistics chief under Michael Collins' IRA.[13] O'Neill and ICA units were involved in various IRA operations during the War of Independence, including the burning of the Custom House in May 1921 and rescue of IRA arms afterward. During the fighting in Dublin that began the Irish Civil War in July 1922, some elements of the ICA (which by this time had about 140 members) were involved in the Anti-Treaty IRA occupation and defence of the Four Courts; while others occupied Liberty Hall, the trade union headquarters, to prevent it falling into the hands of either the Republicans or the Free State Army.

After Irish independence

In the 1920s and 1930s, the ICA was kept alive by veterans such as Seamus McGowan, Dick McCormick and Frank Purcell, though largely as an old comrades association by veterans of the Easter Rising.

Uniformed Citizen Army men provided a guard of honour at Constance Markievicz's funeral in 1927.

In 1934, Peadar O'Donnell and other left-wing republicans left the IRA and founded the Republican Congress. For a brief time, they revived the ICA as a paramilitary force, intended to be an armed wing for their new movement. According to Brian Hanley's history of the IRA, the revived Citizen Army had 300 or so members around the country in 1935. However, the Congress itself split in September 1934, which led to a corresponding split in the ICA. One fraction, which had left the Congress, were led by Michael Price and Nora Connolly O'Brien, while the opposing fraction led by O'Donnell and Roddy Connolly were loyal to those who stayed.

The ICA's last public appearance was to accompany the funeral procession of union leader and ICA founding figure James Larkin in Dublin in 1947.

Uniforms and banners

The ICA uniform was dark green with a slouched hat and badge in the shape of the Red Hand of Ulster.[14] As many members could not afford a uniform, they wore a blue armband, with officers wearing red ones.

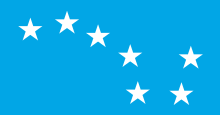

Their banner was the Starry Plough. James Connolly said the significance of the banner was that a free Ireland would control its own destiny from the plough to the stars. The symbolism of the flag was evident in its earliest inception of a plough with a sword as its blade. Taking inspiration from the Bible, and following the internationalist aspect of socialism, it reflected the belief that war would be redundant with the rise of the Socialist International. This was flown by the ICA during the Rising of 1916. The design changed during the 1930s to that of the blue banner on the left, which was designed by members of the Republican Congress, and was adopted as the emblem of the Irish Labour movement, including the Irish Labour Party, though they eventually dropped it. It is also claimed by Irish republicans, and has been carried alongside the Irish tricolour and Irish provincial flags at Official IRA, Provisional IRA, Irish National Liberation Army (INLA), Irish People's Liberation Organisation (IPLO) and Continuity IRA rallies and marches.

The banner, and alternative versions of it, is also used by Republican Sinn Féin, Connolly Youth Movement, Labour Youth, Ógra Shinn Féin, the Irish Republican Socialist Party and the Republican Socialist Youth Movement.

The Troubles

When the Northern Ireland Troubles broke out in 1969 a small group of Republicans carried out a number of sectarian attacks and claimed they were from the Irish Citizen Army. The ICA group from the 1970s was involved in a number of attacks on loyalist areas around Belfast between 1971 - 1973 and in one incident in 1973, shot and injured an SDLP member in Newry.[15] The Irish National Liberation Army was going to use the ICA name first instead of the INLA but decided not to because of the sectarian attacks carried out by the other group.[16]

References

- Charles Townshend, "Easter 1916: The Irish Rebellion", p.41.

- Townshend, p.46.

- "The Irish Citizen Army". BBC.co.uk. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- Yeates, P Lockout: Dublin 1913, Gill and Macmillan, Dublin, 2000, Pages 497-8

- Lyons, F.S.L. (1973). Ireland since the famine. Suffolk: Collins/Fontana. p. 285. ISBN 0-00-633200-5.

- Townshend, p.93.

- Dudley Edwards, "Patrick Pearse", pp.184-197.; Sean Farrell Moran, "Patrick Pearse and the Politics of Redemption", (Washington, DC, 1994); Townshend, p.50.

- Townshend, p.111.

- "The Pooles of 1916 Documentary". Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- Townshend, pp.156-7.

- Dennis L. Dworkin (2012). Ireland and Britain, 1798–1922: An Anthology of Sources. Hackett Publishing. p. 211. ISBN 978-1-60384-741-4. footnote 62

- Brian Hanley, The Irish Citizen Army after 1916 pg 37

- RM Fox, The Irish Citizen Army official history

- Michael McNally, Peter Dennis, Easter Rising 1916: Birth of the Irish Republic, Osprey Publishing

- http://irishistory.blogspot.com/2013/07/irish-republican-paramilitary-groups.html Irish Republican Paramilitary Groups Below is information about each of the Irish Republican Paramilitary groups that was active during the Troubles.

- Jack Holland & Henry McDonald - INLA: Deadly Divisions pp.32-33,pp.54

Bibliography

- Anderson, W.K., James Connolly and the Irish Left (Dublin 1994). ISBN 0-7165-2522-4.

- Fox, R.M., The History of the Irish Citizen Army (Dublin 1943)

- Greaves, C. Desmond, Life and Times of James Connolly, (London 1972)

- Haswell, Jock, Citizen Armies (London 1973)

- Hart, Peter, The IRA at War 1916-1923 (Oxford 2003)

- Hayes-McCoy, G.A., 'A Military History of the 1916 Rising', in K.B.Nowlan (ed.), The Making of 1916. Studies in the History of the Rising (Dublin 1969)

- Martin, F.X., Leaders and Men of the Easter Rising: Dublin 1916 (London 1967)

- O'Casey, Sean (as P. Ó Cathasaigh) Story of the Irish Citizen Army (Dublin 1919)

- O'Drisceoil, Donal, Peadar O'Donnell (Cork 2000)

- Perry, Ciaran, The Irish Citizen Army, Labour clenches its fist!

- Phelan, Mark, 'World War I and the Legacy of the Dublin Lockout, 1914-1916', in Éire-Ireland (Winter, 2016)

- Robbins, Frank. 1978. Under the Starry Plough: Recollections of the Irish Citizen Army. Dublin: The Academy Press. ISBN 0-906187-00-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Irish Citizen Army. |