1861 Atlantic hurricane season

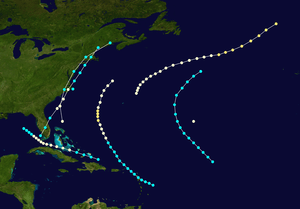

The 1861 Atlantic hurricane season occurred during the first year of the American Civil War[1] and had some minor impacts on associated events. Eight tropical cyclones are believed to have formed during the 1861 season; the first storm developed on July 6 and the final system dissipated on November 3. Six of the eight hurricanes attained Category 1 hurricane status or higher on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale, of which three produced hurricane-force winds in the United States. No conclusive damage totals are available for any storms. Twenty-two people died in a shipwreck off the New England coast, and an undetermined number of crew members went down with their ship in the July hurricane. Based on maximum sustained winds, the first and third hurricanes are tied for the strongest of the year, although the typical method for determining that record—central barometric air pressure—is not a reliable indicator due to a general lack of data and observations.

| 1861 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | July 6, 1861 |

| Last system dissipated | November 3, 1861 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | One and Three |

| • Maximum winds | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total storms | 8 |

| Hurricanes | 6 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 0 |

| Total fatalities | At least 22 |

| Total damage | Unknown |

Four tropical storms from 1861 had been previously identified by scholars and hurricane experts, but three more were uncovered in modern-day reanalysis. Known tracks for most of the systems are presumed to be incomplete, despite efforts to reconstruct the paths of older tropical cyclones. Three systems completely avoided land. They all had an effect on shipping, in some cases inflicting severe damage on vessels. A storm in September, referred to as the "Equinoctial Storm", hugged the East Coast of the United States and produced rainy and windy conditions both along the coast and further inland. The last storm of the season followed a similar track, and affected a large Union fleet of ships sailing to South Carolina for what would become the Battle of Port Royal. Two vessels were sunk and several others had to return home for repairs. Ultimately the expedition ended in a Union success.

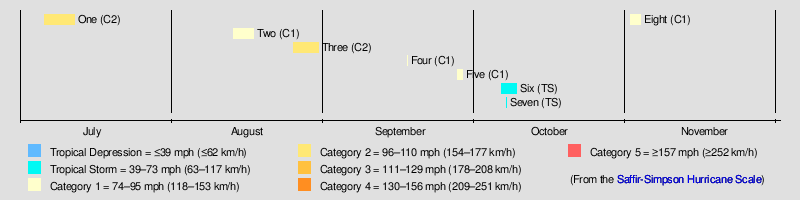

Timeline

Methodology

Prior to the advent of modern tropical cyclone tracking technology, notably satellite imagery, many hurricanes that did not affect land directly went unnoticed, and storms that did affect land were not recognized until their onslaught. As a result, information on older hurricane seasons was often incomplete. Modern-day efforts have been made and are still ongoing to reconstruct the tracks of known hurricanes and to identify initially undetected storms. In many cases, the only evidence that a hurricane existed was reports from ships in its path. Judging by the direction of winds experienced by ships, and their location in relation to the storm, it is possible to roughly pinpoint the storm's center of circulation for a given point in time. This is the manner in which three of the eight known storms in the 1861 season were identified by hurricane expert José Fernández Partagás's reanalysis of hurricane seasons between 1851 and 1910. Partagás also extended the known tracks of most of the other tropical cyclones previously identified by scholars. The information Partagás and his colleague uncovered was largely adopted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Atlantic hurricane reanalysis in their updates to the Atlantic hurricane database (HURDAT), with some slight adjustments. HURDAT is the official source for such hurricane data as track and intensity, although due to a sparsity of available records at the time the storms existed, listings on some storms are incomplete.[2][3]

Although extrapolated peak winds based on whatever reports are available exist for every storm in 1861, estimated minimum barometric air pressure listings are only present for the three storms that directly affected the United States.[4] Two hurricanes during the year made landfall on the mainland United States, and as they progressed inland, information on their meteorological demise was limited. As a result, the intensity of these storms after landfall and until dissipation is based on an inland decay model developed in 1995 to predict the deterioration of inland hurricanes.[3]

Systems

Hurricane One

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 6 – July 12 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min) |

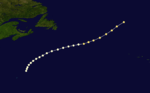

The first tropical cyclone and hurricane of the 1861 season is believed to have formed on July 6, immediately east of the Leeward Islands. A 1938 publication documented the storm's effects on Guadeloupe and St. Kitts, and given a lack of prior reports on the cyclone, modern-day reassessments concluded that it was relatively weak when it affected those islands.[5] After crossing the northern Leeward Islands, the tropical storm broadly curved toward the northwest, likely intensifying into the equivalence of a Category 1 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale on July 9.[2] The majority of the storm's track in the western Atlantic was unknown until it was reconstructed based on reports from, and the effects on, three ships in its vicinity.[5]

On July 10—when the storm was approaching or at its peak intensity with winds of 100 mph (160 km/h)[2]—the Bowditch encountered severe hurricane conditions which destroyed both of her masts and washed her entire crew overboard. Her captain was able to climb back aboard, where he survived for over a week with no food or water until he was rescued by a schooner. The Echo and Creole both sustained significant damage, and the crew and captain of the latter ship had to be rescued after she began taking on water. The extent of the damage to the three ships served as the basis for evaluating the storm's intensity in Partagás's paper.[5] The hurricane ultimately passed between Bermuda and the United States before dissipating after July 12.[2]

Hurricane Two

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 13 – August 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min) 978 mbar (hPa) |

The Key West Hurricane of 1861 [6]

A month after the dissipation of the first hurricane, another tropical storm formed north of Hispaniola on August 13.[2] Ludlum (1963) described the "Key West Hurricane" between August 14 and 16,[7] and it was determined that the system had, in fact, surpassed the threshold for hurricane status based on wind observations from two ships.[3] The storm skirted the north coast of Cuba as it moved west-northwest and passed through the Florida Straits.[2] On or around August 15, Havana, Cuba experienced heavy rainfall.[7] Although the cyclone did not directly make landfall, it delivered hurricane-force winds to southern Florida.[4] It turned more toward the northwest as it entered the Gulf of Mexico, where it began to gradually weaken. It is listed as having dissipated on August 17 in the northern Gulf.[2]

The hurricane damaged or wrecked numerous vessels. Six ships were wrecked or grounded in the Bahamas, and the crews of at least two, the John Stanley and the Linea, had to be rescued. The steamship Santiago de Cuba left port on August 4, and began to encounter squally conditions later that afternoon. Heavy seas and a strong gale inflicted some damage on the vessel. Several ships along the eastern coast of Cuba were wrecked during the storm, leading to great uncertainty and concern regarding the fate of the Santiago. At least three vessels were lost or grounded along the Florida Keys.[7]

Hurricane Three

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 25 – August 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min) 958 mbar (hPa) |

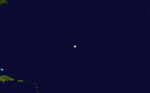

The first storm to be uncovered in modern-day reanalysis existed in late August, and ties the July hurricane for the strongest system of the season in terms of maximum sustained winds. Its track is known between August 25 and August 30, during which time it progressed generally northeasterly from a point northeast of the island of Bermuda to the central northern Atlantic.[2][8] On August 30, the Harvest Queen recorded a barometer of 28.30 inHg (958 hPa) on August 30; this report was a strong indication that the storm had attained hurricane intensity, although the system was likely undergoing its transition into an extratropical cyclone at the time.[9]

Hurricane Four

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 17 – September 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min) |

The subsequent hurricane was also previously unrecognized until contemporary research, although the majority of its track remains unknown. The only indication that a tropical cyclone existed was the ship David G. Wilson, which was dismasted by a severe storm on September 17. As no other information is available on the hurricane, it is listed in the Atlantic hurricane database as a single point in the central Atlantic (at 28.5°N, 50°W).[9]

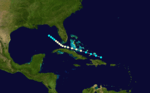

Hurricane Five

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 27 – September 28 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min) 985 mbar (hPa) |

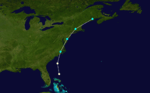

The first storm to directly strike the mainland United States was first detected on September 27, off the east coast of the Florida peninsula.[2] The storm is estimated to have been a minimal hurricane based on observations from the ship Virginia Ann.[3] Several other vessels encountered the storm along its track, including the steamship Marion, which experienced hours of violent winds, torrential rainfall, and frequent thunder and lightning.[9] The hurricane curved north, then northeast, striking North Carolina that same day before speeding northeastward as it hugged the United States East Coast. Its track is only known through 1200 UTC on September 28.[2] Ludlum (1963) refers to the hurricane as the "Equinoctial Storm", and describes its area of impact as the "entire coast".[10]

In the aftermath of the Battle of Carnifex Ferry in present-day West Virginia, Rutherford B. Hayes of the 23rd Ohio Infantry was camped south of the battle site, where he wrote about a "very cold rain-storm" in a September 27 letter to his wife Lucy. Conditions at the time were characterized by leaking tents and temperatures getting "colder and colder". Hayes wrote, "We were out yesterday P.M. very near to the enemy's works; were caught in the first of this storm and thoroughly soaked. I hardly expect to be dry again until the storm is over."[11] Strong winds buffeted the Burlington, New Jersey, area from early evening to midnight on September 27, uprooting trees and causing some damage to property. Further north, Boston, Massachusetts, experienced intense winds and light rainfall for about five hours starting at midnight, with no initial reports of significant destruction.[9]

Tropical Storm Six

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 6 – October 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) |

Two tropical systems are known to have existed during the month of October. The first was originally documented by Partagás (1995), who detected it based on a faulty report of a violent gale from a ship, the Mariquita. The report was said to have been from October 16, but given her arrival date in New York City four days later and her location at the time of her encounter with the storm, she probably encountered the cyclone much earlier in the month. The violent south-southwesterly gale lasted 15 hours when the vessel was probably located at 20.5°N, 47°W. The storm was initially assigned a single set of coordinates for October 6, and no attempt was made to reconstruct its track due to a lack of certain data on it. However, it was noted that a ship further north on October 9 experienced a heavy gale.[12] Based on the likely correlation between the two ship reports, the storm's track was extended four days to late on October 9 in the Atlantic hurricane database.[3]

Tropical Storm Seven

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 7 – October 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) |

A 1960 publication mentioned a tropical storm near Cape Hatteras, North Carolina sometime in October 1861 without specifying a date. Newspaper reports indicate that ships mainly north of the Cape Hatteras area encountered strong northerly gales for several days starting on October 7, and winds in New York City persisted from October 7 to October 10 with a northerly component. Partagás (1995) noted, "These findings do not seem to support a tropical system but the author made the decision of retaining the storm [...] due to the lack of solid evidence against its existence."[12] However, little is known about the system, and its inclusion in the hurricane database is limited to a single point at 35.3°N, 75.3°W.[2]

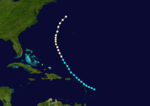

Hurricane Eight

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | November 1 – November 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min) 985 mbar (hPa) |

The Expedition Hurricane of 1861 [13]

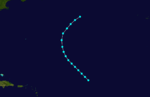

The final storm of the season followed a generally north-northeasterly course from the Gulf of Mexico northward along the U.S. East Coast between November 1 and November 3, dissipating over New England. The storm crossed southern Florida,[2] and based on observations from Hatteras Inlet, North Carolina, and observations from the ship Honduras, it is believed to have attained hurricane intensity.[3] The hurricane made landfall in eastern North Carolina and proceeded up the coast before crossing eastern Long Island and coming ashore in southern New England. Its demise on November 3 marked the end of the 1861 Atlantic hurricane season; the next tropical storm would not form in the Atlantic until June 1862.[2] Two storm systems affected the region in the week following October 28, both of which influenced a Civil War expedition which was "the largest fleet of war ships and transports ever assembled".[14][15]

The first storm, which is not recognized as a tropical cyclone, disrupted the initial assembly of the fleet on October 28. However, the fleet set sail the next day on its mission to attack Confederate forces (its destination was "supposedly a military secret"[14]). On November 2, the expedition encountered the second storm—the tropical hurricane—which wreaked havoc on the organization of the fleet and sunk two of its vessels. There was knowledge at the time of the series of storm systems, but few details on the condition and fate of the fleet, sparking great concern.[14] Some of the other ships were forced to return home for repairs, but the majority rode out the storm successfully.[16] The expedition proceeded onward and seized Port Royal Sound at the Battle of Port Royal. As described by Ludlum (1963), the hurricane is known as the Expedition Hurricane due to its influence on the fleet.[14]

However, the hurricane also had a significant impact on land. Earlier in the year, Union forces had captured the fort guarding Hatteras Inlet at the Battle of Hatteras Inlet Batteries. In the early morning hours of November 2, high seas began to overwash Hatteras Island, "completely covering all dry land except the position of the fort itself".[14] After four hours, water began to subside. Extremely high tides associated with the cyclone continued up the coast as far north as Portland, Maine. Storm tides at various points, including New York City, Newport, Rhode Island, and Boston, reached levels unseen for at least 10 years and up to 46 years. In New York, the storm persisted for 20 hours starting early on November 2; rising waters inundated wharves along the East and Hudson Rivers. Floodwaters flowed up to five blocks inland, and a popular bar located in a hotel became isolated by the flooding. In response, a man transported customers to and from the bar on his private boat at a cost of two cents per ride.[17] Strong winds in Brooklyn brought down trees and telegraph wires.[17]

Infrastructure throughout the Tri-State area suffered. Parts of the New Jersey Railroad line were undermined, and the Shore Line Railway at Bridgeport was inundated. Flooding was also prominent in the New Jersey Meadowlands and along the Newark Turnpike and Plank Road, which was left temporarily impassable. Further east, the hurricane triggered coastal flooding along the shores of Long Island, while northeasterly winds blew several ships ashore along the northern coast of Long Island. The eastern side of the hurricane blasted the southeastern New England coast between November 2 and November 3, damaging over 250 vessels at Provincetown, Massachusetts, and running aground 20 others. Water from the Massachusetts Bay surged into the village of Wareham. In downtown Boston, the storm began late on November 2 and lasted until late the next morning, although the highest tides did not occur until after conditions had already cleared. Twenty-two occupants of the ship Maritania drowned when the vessel sank after striking a rock during the worst of the storm. At the time, she was located 1 mi (1.6 km) east of the Boston Light.[17]

See also

Notes

- Symonds, Craig. "American Civil War (1861–1865)". The New York Times. Retrieved August 20, 2011.

- Hurricane Specialists Unit (2009). "Easy to Read HURDAT 1851–2008". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved July 15, 2011.

- Hurricane Research Division (2011). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-04.

- Hurricane Research Division (2011). "Continental U.S. Hurricanes: 1851 to 1930, 1983 to 2010". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2011-06-04.

- Partagás, p. 1

- Early American hurricanes 1492-1870, David Ludlum, pg

- Partagás, p. 2

- Partagás, pp. 2–3

- Partagás, p. 3

- Ludlum, p. 194

- Rutherford Birchard Hayes (1922). Diary and Letters of Rutherford Birchard Hayes: 1861–1865. The Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society. p. 102. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

1861 Equinoctial Storm.

- Partagás, p. 5

- Early American hurricanes 1492-1870, David Ludlum, pg 101

- Ludlum, p. 101

- David Roth. "Late Nineteenth Century Virginia Hurricanes". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- Browning, pp. 29–30

- Ludlum, p. 102

References

- Browning, Robert M. Jr., Success is all that was expected; the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron during the Civil War. Brassey's, 2002. ISBN 1-57488-514-6

- Ludlum, David McWilliams (1963). Early American hurricanes, 1492–1870. American Meteorological Society.

- Partagás, José Fernández (1995). "A Reconstruction of Historical Tropical Cyclone Frequency in the Atlantic from Documentary and other Historical Sources: Year 1861" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 15, 2011.