1869 Atlantic hurricane season

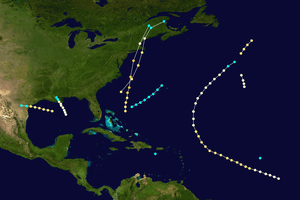

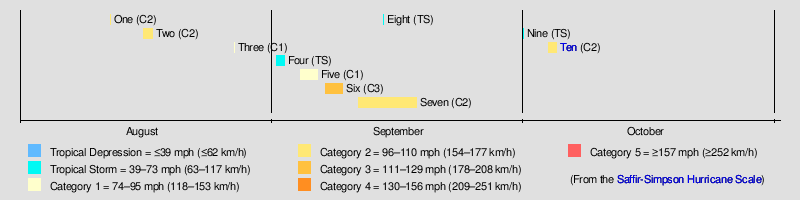

The 1869 Atlantic hurricane season was the earliest season in the Atlantic hurricane database in which there were at least ten tropical cyclones.[1] Initially there were only three known storms in the year, but additional research uncovered the additional storms.[2] Meteorologist Christopher Landsea estimates up to six storms may remain missing from the official database for each season in this era, due to small tropical cyclone size, sparse ship reports, and relatively unpopulated coastlines.[3] All activity occurred in a three-month period between the middle of August and early October.

| 1869 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | August 12, 1869 |

| Last system dissipated | October 5, 1869 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Six |

| • Maximum winds | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 950 mbar (hPa; 28.05 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total storms | 10 |

| Hurricanes | 7 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 1 |

| Total fatalities | 49 |

| Total damage | $50,000 (1869 USD) |

Out of the ten tropical storms, seven reached hurricane intensity, of which four made landfall on the United States. The strongest hurricane was a Category 3 on the modern-day Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale which struck New England at that intensity, one of four storms to do so. It left heavy damage, killing at least twelve people. The most notable hurricane of the season was the Saxby Gale, which was predicted nearly a year in advance. The hurricane was one of six to produce hurricane-force winds in Maine, where it left heavy damage and flooding. The Saxby Gale left 37 deaths along its path, with its destruction greatest along the Bay of Fundy; there, the hurricane produced a 70.9 ft (21.6 m) high tide near the head of the bay.

Timeline

Systems

Hurricane One

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 12 – August 12 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min) |

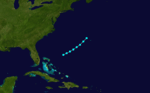

The first tropical cyclone of the season was observed on August 12, about 500 mi (800 km) southeast of Cape Race, Newfoundland. Its entire track was unknown, and its existence was only confirmed for 24 hours, based on three ship reports. The second, a barque, the Prinze Frederik Carl, sustained damage to all of its sails. The Hurricane Research Division (HRD) assessed the storm to have moved northeastward in its limited duration, and based on the ship reports estimated peak winds of 105 mph (165 km/h); this would make it a Category 2 hurricane on the modern-day Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale.[2][4]

Hurricane Two

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 16 – August 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min) 969 mbar (hPa) |

The Lower Texas Coast Hurricane of 1869 [5]

By August 16, a strong hurricane was located in the northwestern Gulf of Mexico south of Louisiana. With estimated winds of 105 mph (165 km/h), it tracked westward and struck Texas on Matagorda Island before passing near Refugio. The hurricane quickly weakened over land and dissipated late on August 17.[4] Damage from the hurricane was heaviest in Refugio and Indianola. In the latter city, strong waves damaged wharves and boats while the storm surge flooded the streets with about 1 ft (0.30 m) of water. Intense winds knocked down several houses as well as a church, and many buildings lost their roofs. In Sabine Pass, the winds ruined a variety of fruit crops.[6]

Hurricane Three

The third hurricane of the season was only known due to it affecting one ship. A vessel in the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company reported a hurricane on August 27, about halfway between Bermuda and the Azores. The storm was estimated to have been moving north-northwestward with winds of 80 mph (130 km/h), although its entire track is unknown.[2]

Tropical Storm Four

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 1 – September 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) |

A tropical storm was first observed on September 1 to the east of the Bahamas. There, it left heavy damage to a brig sailing from Nassau to New York City. The storm tracked generally northeastward, damaging another ship on September 2 near Bermuda.[2]

Hurricane Five

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 4 – September 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min) 985 mbar (hPa) |

On September 4, a hurricane was located in the northern Gulf of Mexico, moving north-northwestward. The next day, it moved ashore in southeastern Louisiana with winds estimated at 80 mph (130 km/h), passing west of New Orleans. It dissipated early on September 6. The hurricane dropped heavy rainfall along its path that caused flooding. In addition, strong winds uprooted trees and damaged fences. High tides flooded Grand Isle with 2 ft (0.61 m) of water.[2][4]

Hurricane Six

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 7 – September 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min) 950 mbar (hPa) |

The New England Gale of 1869

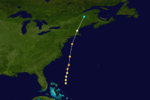

On September 7, three ships observed hurricane-force winds over the western Atlantic Ocean, between the Bahamas and Bermuda. The storm moved northward, impacting several other ships as it paralleled the east coast of the United States; one of them reported a pressure of 956 mbar (28.24 inHg), which indicated the system was an intense hurricane.[2] Late on September 8, it reached a peak intensity of 115 mph (185 km/h) with a pressure of 950 mbar (28.05 inHg). After brushing Long Island, the hurricane weakened slightly and made landfall on southwestern Rhode Island at peak intensity.[7] It was one of three hurricanes, along with the 1938 New England hurricane and Hurricane Carol in 1954, to strike New England as a major hurricane, or Category 3 or higher on the Saffir-Simpson scale.[8]

At landfall, the hurricane was compact, estimated around 60 mi (97 km) wide.[9] However, less than 10 miles (16 km) west of the center, there were no strong winds.[2] The hurricane produced a storm surge of 8 ft (2.4 m),[7] which was lessened due to it moving ashore at low tide.[9] In Providence, Rhode Island, high waves damaged coastal wharves and left flooding.[2] The hurricane weakened quickly over land, passing just west of Boston early on September 9 as a minimal hurricane.[7] There, the winds downed many trees and left severe damage.[2] All telegraph lines between New York and Boston were cut, although the storm did produce beneficial heavy rainfall.[10] Shortly thereafter it dissipated over Maine.[7] There was one confirmed death in Massachusetts.[11] Offshore Maine, a schooner capsized, killing all but one of the twelve crew.[12] The storm also caused at least $50,000 (1869 USD) in damage in Maine alone.[13][14]

Hurricane Seven

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 11 – September 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min) 979 mbar (hPa) |

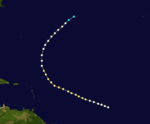

A ship about halfway between South America and Cape Verde reported a hurricane on September 11. The storm tracked generally west-northwestward, affecting several other ships with damaging winds. On September 15, a ship traveling from St. Thomas to England encountered the hurricane and observed a minimum barometric pressure of 979 mbar (28.90 inHg);[4][2] this suggested peak winds of 105 mph (165 km/h).[7] By September 16 the hurricane had weakened slightly as its track turned to the north and northeast. It was last observed on September 18 to the west of the Azores as a tropical storm.[4]

Tropical Storm Eight

The only basis for identifying the eighth tropical cyclone of the season was from a report by the bark Crescent Wave. On September 14, the ship encountered strong winds and heavy rainfall about halfway between the Lesser Antilles and Cape Verde. At the time, the storm was at least 600 mi (970 km) east of the previous hurricane.[2]

Tropical Storm Nine

On October 1, the brig Jenny observed "a revolting gale lasting 3 days" off the south coast of Puerto Rico, which indicated a tropical storm in the region. Despite being located near several islands in the Caribbean, no land stations experienced any effects from the storm.[2]

Hurricane Ten

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 4 – October 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min) 965 mbar (hPa) |

Saxby Gale

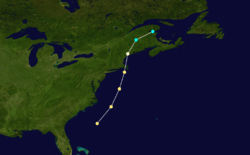

The final hurricane of the season was first observed on October 4 by a ship off the southeast coast of North Carolina. With winds estimated at 105 mph (165 km/h), the storm tracked northeastward, passing just east of Martha's Vineyard before moving across Cape Cod late on October 4.[2][7] As it moved along the coast, the storm produced heavy precipitation, reaching 12.25 in (311 mm) in Canton, Connecticut.[15] The strongest winds did not affect Massachusetts, although a few hours later the hurricane struck just east of Portland, Maine at peak intensity.[2][7] This made it one of six storms to produce hurricane-force winds in Maine, along with Hurricane Carol in 1953, Hurricane Edna in 1954, Hurricane Donna in 1960, Hurricane Gerda in 1969, and Hurricane Gloria in 1985.[8] In Maine, the high rainfall caused widespread flooding, while the high winds destroyed at least 90 houses.[15] The hurricane quickly weakened over land, and after turning northeastward into Atlantic Canada dissipated on October 5 near the Gulf of St. Lawrence.[7]

The hurricane was referred as Saxby's Gale after Lieutenant S.M. Saxby of the Royal Navy predicted in November 1868 that an unusually violent storm would produce very high tides on October 5; he did not specify the location, however. Although heavy damage occurred in New England, the devastation was greatest in Atlantic Canada along the Bay of Fundy. The hurricane produced a storm surge of around 7 ft (2.1 m),[2][7] which, in combination with the winds, the low pressure, and being in a region of naturally occurring high tides, produced a 70.9 ft (21.6 m) high tide near the head of the bay.[16] The high tides surpassed the dykes across New Brunswick and left widespread flooding, killing many cattle and sheep and washing away roads. In the Cumberland Basin, the floods washed two boats about 3 mi (5 km) inland. In Moncton, water levels rose about 6.6 ft (2 m) higher than the previous highest level.[17] There were 37 deaths between Maine, New Brunswick, and New York.[18][19]

See also

References

- Hurricane Research Division (2011). "Atlantic basin: Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2011-03-18.

- José Fernández Partagás (2003). "Year 1869" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2011-03-12.

- Chris Landsea (2007-05-01). "Counting Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Back to 1900" (PDF). Eos. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 88 (18): 197–208. Bibcode:2007EOSTr..88..197L. doi:10.1029/2007EO180001. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 January 2011. Retrieved 2011-01-18.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- Early American hurricanes 1492-1870, David Ludlum, pg 182-183

- David M. Roth (2010-04-08). "Louisiana Hurricane History" (PDF). Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved 2010-12-01.

- Hurricane Research Division (2008). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2011-03-14.

- Hurricane Research Division (December 2010). "Chronological List of All Hurricanes which Affected the Continental United States: 1851–2010" (TXT). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2011-03-13.

- "Commonwealth of Massachusetts". Commonwealth of Massachusetts. 2011. Archived from the original on 13 March 2011. Retrieved 2011-03-14.

- Staff Writer (1869-09-09). "Great Storm East-Telegraphic Communication Interrupted" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-03-15.

- Edward N. Rappaport and Jose Fernandez-Partagas (1996). "The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492–1996: Cyclones that may have 25+ deaths". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-03-14.

- "Hurricanes & Tropical Storms Their Impact on Maine and Androscoggin County" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-01. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- "Hurricanes & Tropical Storms Their Impact on Maine and Androscoggin County" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-01. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- Early American hurricanes 1492-1870, David Ludlum, pg 103-107

- Keith C. Heidorn (2010-10-01). "The Saxby Gale: A Lucky Guess?". Islandnet.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2011-03-17.

- Jon A. Percy (2001). "Fundy's Minas Basin: Multiplying the Pluses of Minas". Bay of Fundy Ecosystem Partnership. Archived from the original on 2012-03-21. Retrieved 2011-03-17.

- Danika van Proosdij (2009-10-22). "Assessment of Flooding Hazard along the Highway 101 corridor near Windsor, NS using LIDAR" (PDF). Government of Nova Scotia. p. 16. Retrieved 2011-03-17.

- Edward N. Rappaport and Jose Fernandez-Partagas (1996). "The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492–1996: Cyclones with 25+ deaths". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-03-14.

- Early American hurricanes 1492-1870, David Ludlum, pg 108-111