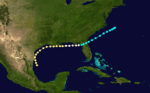

1867 Atlantic hurricane season

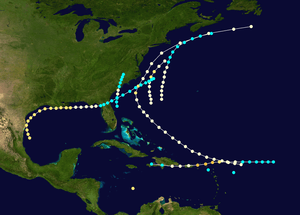

The 1867 Atlantic hurricane season lasted from mid-summer to late-fall. A total of nine known tropical systems developed during the season, with the earliest forming on June 21, and the last dissipating on October 31. On two occasions during the season, two tropical cyclones simultaneously existed with one another; the first time on August 2, and the second on October 9. Records show that 1867 featured two tropical storms, six hurricanes and one major hurricane (Category 3+). However, in the absence of modern satellite and other remote-sensing technologies, only storms that affected populated land areas or encountered ships at sea were recorded, so the actual total could be higher. An undercount bias of zero to six tropical cyclones per year between 1851 and 1885 and zero to four per year between 1886 and 1910 has been estimated.[1] Of the known 1867 cyclones Hurricanes Three, Four and Six plus Tropical Cyclones Five and Eight were first documented in 1995 by Jose Fernandez-Partagas and Henry Diaz.[2] Hurricane One was first identified in 2003 by Cary Mock.[3]

| 1867 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | June 21, 1867 |

| Last system dissipated | October 31, 1867 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Nine |

| • Maximum winds | 125 mph (205 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 952 mbar (hPa; 28.11 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total storms | 9 |

| Hurricanes | 6 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 1 |

| Total fatalities | 811+ |

| Total damage | At least $1 million (1867 USD) |

The strongest storm of the season was Hurricane Nine, or the San Narciso hurricane. It developed in the Central Atlantic, and moved west to impact the Leeward Islands and Greater Antilles. The storm system was a major Category 3 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson hurricane scale, meaning the hurricane had maximum sustained winds of 111–130 mph (178–209 km/h). This was the costliest, and deadliest, storm of the season, causing at least $1 million (1867 USD) in damage, and at least 800 deaths[4] across the Caribbean Sea.

Timeline

Systems

Hurricane One

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 21 – June 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min) 985 mbar (hPa) |

On the morning of June 21, a tropical storm formed approximately 65 mi (105 km) east northeast of Daytona Beach, Florida. Initially below hurricane strength with a maximum sustained wind speed of 60 mph (97 km/h), the tropical storm moved almost due north, while strengthening steadily. By the early hours of June 22, the system had intensified into a Category 1 hurricane, while moving slowly east northeastward. Early on June 23 the hurricane made landfall east of the city of Charleston, South Carolina, with peak winds of 80 mph (130 km/h). In Charleston a number of roofs were blown away, trees were uprooted and wharves damaged. Outside the city there was considerable damage to crops due to heavy rainfall. Weakening steadily, the system's last known location was near Raleigh, North Carolina, on June 23.[3]

Hurricane Two

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 28 – August 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min) 969 mbar (hPa) |

The bark St. Ursula observed a hurricane about 375 mi (600 km) east-northeast of Dominica of July 28.[2] Tracking generally northwestward, the storm changed little in intensity until located to the north of Grand Turk. From there, it proceeded northwestward, and intensified to near Category 1 hurricane status. As it moved to the southwest of Wilmington, North Carolina, the storm attained its peak intensity of 105 mph (165 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 969 mbar (28.6 inHg),[5] based on observations from a ship located about 140 mi (230 km) east of Norfolk, Virginia.[2] Shortly thereafter, the cyclone commenced re-curving to the northeast and began a weakening trend, falling to Category 1 strength by early on August 2. Further weakening occurred while the hurricane was located to the west of Sable Island. The storm was last reported to the south of Cape Race on the island of Newfoundland on August 3.[5]

The town of Marblehead, Massachusetts, recorded 11 deaths after a fishing schooner went missing in a gale near Sable Island.[6] On Nantucket, the island reported gale-force winds from the southeast, torrential rainfall, and waves washing over 8 to 10 ft (2.4 to 3.0 m) hills. The winds damaged crops, especially corn and garden vegetables, while toppling large trees, chimneys, and fences. Waves displaced "millions of loads of sand" into Hummock Pond, while also cutting a 100 ft (30 m) channel from the pond into the ocean.[7] At least two additional deaths occurred offshore the East Coast of the United States after a brig sank.[8]

Hurricane Three

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 2 – August 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min) |

Early on August 2, a hurricane developed over the central Caribbean Sea. The storm reached an estimated peak intensity of 100 mph (160 km/h), making it a Category 2 hurricane. The report of the hurricane was based on observations from the ship Suwanee, with no other reports available.[3]

Hurricane Four

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 31 – September 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min) |

Late on August 31, a Category 1 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) was reported over the Central Atlantic. Moving generally north to north-northeast, the storm gained no intensity over the next day or so as it passed between the United States East Coast and Bermuda. Late on September 2, the storm retained tropical storm status as it paralleled the coast of Washington, D.C. Retracing to the east at an increasing forward speed, the storm system held its intensity of 70 mph (110 km/h) for the rest of its existence. Observations from the ship Helen R. Cooper confirm that this storm was in fact a hurricane.[3]

Tropical Storm Five

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 8 – September 8 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) |

Early on September 8, the schooner Matilda encountered a tropical cyclone two hundred miles to the east of the Leeward Islands.[2] The storm's recorded wind speeds reached no more than 60 mph (97 km/h), and there were no further reports of it on subsequent days.[5]

Hurricane Six

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 29 – October 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min) |

Late on September 29, a Category 1 hurricane formed several hundred miles north of the Bahamas. Tracking to the north, the storm system gained very little strength while passing several hundred miles southwest of Savannah, Georgia. It reportedly attained Category 2 hurricane status while located approximately 100 mi (160 km) to the east of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, with winds peaking at 100 mph (160 km/h). Spinning to the north-northeast, the hurricane eventually entered a weakening phase, and its last reported location was approximately 285 mi (459 km) northeast of Virginia Beach, Virginia. This hurricane never made landfall.[5]

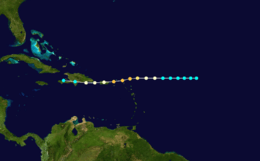

Hurricane Seven

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 2 – October 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min) 969 mbar (hPa) |

The Galveston Hurricane of 1867

Late on October 2, a hurricane formed in the Gulf of Mexico, off the coast of northeastern Mexico. Holding its intensity, the storm system paralleled the Texas coastline, causing "many" deaths. A storm tide value of 7 feet (2.1 m) was reported in Ludlum (1963), and it is possible that Brownsville, Texas, was in the western eyewall of the hurricane at the storms closest approach.[3] Turning towards Louisiana, the storm made landfall on the state with winds of 100 mph (160 km/h), a Category 2 on the Saffir-Simpson hurricane scale. Moving to the east and weakening, the storm made landfall on the state of Florida during the day on October 6. Holding its strength while crossing the Sunshine state, the tropical storm re-emerged into Atlantic waters. Taking a slight turn to the north, it dissipated off the coast of North Carolina on October 9.[5]

The hurricane struck Texas, near the mouth of the Rio Grande, and devastated Brownsville, Matamoros, and Bagdad. Because of the devastating effects in these three, state authorities sought help from the governors of Nuevo León and Coahuila. The governor of Nuevo León authorized the state to send over 100 bushels of corn; Coahuila's sent 500 loads of flour. Relief was also sent from Veracruz in two vessels. Agriculturalists in Matamoros were allowed to send their goods to Monterrey for storage. The entire population of Bagdad fled, while Matamoros was left nearly in ruins. The official death toll in the area was unknown, but local accounts stated there were at least 26 dead. Entire families disappeared from the area too.[9]

Most buildings in Brazos Santiago were leveled. Clarksville, two miles inland, was also devastated and shortly later abandoned.[10] Galveston, already in the midst of a yellow fever epidemic, was flooded by a storm surge. The mainland rail bridge, a hotel and hundreds of homes in the city were washed away. Twelve schooners and a river steamboat were wrecked in the bay there and wharves destroyed.[11] On October 3 high seas and heavy rains flooded New Orleans. Bath houses and a saw mill there were blown away. Houses were also swept away at Milneberg and at Pilottown, Louisiana. The Ship Shoal Light was damaged while the Shell Keys lighthouse was destroyed and its keeper killed. High winds and heavy rainfall continued across southeast Louisiana until October 6, inflicting great damage on crops.[12][13]

Tropical Storm Eight

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 9 – October 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) |

This tropical storm is known from having wrecked the schooner Three Sisters on the night of October 9 at Saint Martin in the eastern Caribbean. It may also have been responsible for seven inches of rain falling on Barbados on October 7 but that is uncertain.[2] It is estimated that the storm reached its peak with winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) on October 9.[5]

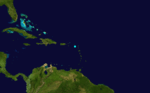

Hurricane Nine

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 27 – October 31 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 125 mph (205 km/h) (1-min) 952 mbar (hPa) |

Hurricane San Narciso of 1867

The mail steamer Principe Alfonso first observed this cyclone about 750 mi (1,205 km) east-northeast of Barbuda around 00:00 UTC on October 27.[2][5] Moving westward, the storm intensified, becoming a hurricane on the following day. The system further strengthened into a major hurricane, reaching Category 3 early on October 29. Around that time, the hurricane made landfall on Sombrero Island. The storm peaked with winds of 125 mph (205 km/h) and a pressure of 952 mbar (28.1 inHg) shortly before striking Saint Thomas in the United States Virgin Islands. Late on October 29, the hurricane struck northeastern Puerto Rico near Fajardo with winds of 115 mph (185 km/h). The cyclone quickly weakened to a Category 1 over the island before emerging into the Mona Passage. On October 30, the system struck just southwest of Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, as a Category 1 hurricane. Mountainous terrain caused the storm to rapidly weaken and dissipate over Haiti on the following day.[5]

The hurricane left extensive impact in the British Virgin Islands, with the storm destroying about 100 homes on Virgin Gorda and 60 out of 123 homes on Tortola. Most sugar plantations and many crops were damaged. At least 39 deaths occurred in the British Virgin Islands, including 37 on Tortola and 2 on Peter Island. At Saint Thomas, the hurricane destroyed about 80 ships, including the RMS Rhone. On the island itself, the cyclone caused approximately 600 deaths.[14] A death toll of 211, mostly due to drowning by floods or landslides, was reported on Puerto Rico, while the hurricane destroyed fourteen vessels and sixteen bridges on the island. Extensive damage occurred to the Puerto Rico's agriculture.[15] In Dominican Republic, the cyclone nearly destroyed the city of Santo Domingo and caused about 200 additional deaths.[2]

See also

References

- Landsea, C. W. (2004). "The Atlantic hurricane database re-analysis project: Documentation for the 1851–1910 alterations and additions to the HURDAT database". In Murname, R. J.; Liu, K.-B. (eds.). Hurricanes and Typhoons: Past, Present and Future. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 177–221. ISBN 0-231-12388-4.

- Fernández-Partagás, José; Diaz, Henry F. (1997). A Reconstruction of Historical Tropical Cyclone Frequency in the Atlantic from Documentary and other Historical Sources (part 1). Boulder, Colorado: Climate Diagnostics Center, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- Hurricane Research Division (2008). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- Rappaport, Edward N. & Fernandez-Partagas, Jose (1996). "The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492–1996: Cyclones with 25+ deaths". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- Ancestry.com. Massachusetts, Town and Vital Records, 1620-1988 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011. Original data: Town and City Clerks of Massachusetts. Massachusetts Vital and Town Records. Provo, UT: Holbrook Research Institute (Jay and Delene Holbrook).

- "Effects of a Gale". New England Farmer. August 17, 1867. p. 3. Retrieved August 10, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- Rappaport, Edward N. & Fernandez-Partagas, Jose (1996). "The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492–1996: Cyclones that may have 25+ deaths". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- Escobar Ohmstede, Antonio (August 1, 2004). Desastres agrícolas en México: catálogo histórico (Volumen 2) (in Spanish). Centro de Investigación y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social. p. 97. ISBN 9681671880.

- David Roth (February 4, 2010). "Texas Hurricane History" (PDF). National Weather Service. Retrieved June 22, 2011.

- W.T.Block (February 19, 1978). "Texas Hurricanes of the 19th Century: Killer Storms Devastated Coastline". The Beaumont Enterprise. Retrieved November 24, 2012.

- David M. Roth (January 13, 2010). Louisiana Hurricane History (PDF). National Weather Service, Southern Region Headquarters. Retrieved January 25, 2011.

- Early American hurricanes 1492-1870, David Ludlum, pg 179-182

- "Oct. 29 Marks Anniversary of 2 Unforgettable Hurricanes". Virgin Islands Source. October 29, 2013. Retrieved August 10, 2019.

- Colón, José (1970). Pérez, Orlando (ed.). Notes on the Tropical Cyclones of Puerto Rico, 1508–1970 (Pre-printed) (Report). National Weather Service. p. 26. Retrieved September 27, 2012.