Dallas County, Alabama

Dallas County is a county located in the central part of the U.S. state of Alabama. As of the 2010 census, its population was 43,820.[1] The county seat is Selma.[2] Its name is in honor of United States Secretary of the Treasury Alexander J. Dallas, who served from 1814–1816.

Dallas County | |

|---|---|

Dallas County Courthouse in Selma. Built in 1901, it was given an extensive modern makeover in 1960 | |

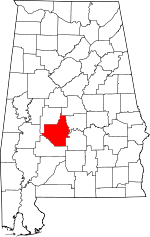

Location within the U.S. state of Alabama | |

Alabama's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 32°19′29″N 87°06′19″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | February 9, 1818 |

| Named for | Alexander J. Dallas |

| Seat | Selma |

| Largest city | Selma |

| Area | |

| • Total | 994 sq mi (2,570 km2) |

| • Land | 979 sq mi (2,540 km2) |

| • Water | 15 sq mi (40 km2) 1.5%% |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 43,820 |

| • Estimate (2019) | 37,196 |

| • Density | 44/sq mi (17/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Congressional district | 7th |

| Website | www |

| |

Dallas County comprises the Selma, AL Micropolitan Statistical Area.

History

Dallas County was created by the Alabama territorial legislature on February 9, 1818, from Montgomery County. This was a portion of the Creek cession of lands to the US government of August 9, 1814. The Creek were known as one of the Five Civilized Tribes of the Southeast. The county was named for U.S. Treasury Secretary Alexander J. Dallas of Pennsylvania.

Dallas County is located in what has become known as the Black Belt region of the west-central portion of the state. The name referred to its fertile soil, and the area was largely developed for cotton plantations, worked by enslaved African Americans in the antebellum period. After emancipation following the Civil War, many of the African Americans who stayed in the area worked as sharecroppers and tenant farmers. The county has been majority black since before the war because of the numerous slaves who worked the plantations.

Dallas County produced more cotton by 1860 than any other county in the state, requiring a large supply of workers, which were drawn from enslaved people. Dallas County slave owners on average had seventeen enslaved workers (compared to ten in Montgomery County, for instance); slave owners made up some 16% of the county's white population, but if their families are added, at least a third of the county's population was attached to a slaveholding family, according to historian Alston Fitts.[3]

Well-known local slaveowners include Washington Smith, owner of a big plantation in Bogue Chitto, Alabama, near Selma, and founder of the Bank of Selma, who even after Emancipation continued to exert great influence over the African-American people in the county.[4] Smith had bought Redoshi, on whom he forced the name Sally Smith, a West-African woman from Benin who had been kidnapped at age 12 and sold after being transported on the Clotilda, which carried enslaved Africans to America over 50 years after the slave trade had been abolished.[5]

The county is traversed by the Alabama River, flowing from northeast to southwest across the county. It is bordered by Perry, Chilton, Autauga, Lowndes, Wilcox, and Marengo counties. Originally, the Dallas county seat was at Cahaba, which also served as the state capital for a brief period. In 1865, the county seat was transferred to Selma, Alabama as the center of population had moved. Other towns and communities in the still mostly rural county include Marion Junction, Sardis, Orrville, Valley Grande, and Minter.

20th century to present

Cotton production suffered in the early 20th century due to infestation of boll weevil, which invaded cotton areas throughout the South. At the turn of the 20th century, the state legislature disenfranchised most blacks and many poor whites through provisions of a new state constitution requiring payment of poll tax and passing a literacy test for voter registration. These largely survived legal challenges and blacks were excluded from the political system.

The period from 1877 to 1950 (and especially 1890 through 1930), was the height of lynchings across the South, as whites worked to impose white supremacy and Jim Crow. According to the third edition of Lynching in America, Dallas County had 19 lynchings in this period, the second-highest number of any county in the state after Jefferson County.[6] The lynching mobs killed suspects of alleged crimes, but also for behavior that offended a white man, and for labor organizing.[7][6] In the early and mid-20th century, a total of 6.5 million blacks left the South in the Great Migration to escape these oppressive conditions.

In the postwar era of the 1950s and 1960s, African Americans, including many veterans, mounted new efforts across the South to be able to exercise their constitutional right as citizens to register and vote.[7]

The still mostly rural county reached a peak of population in 1960. Younger people have since left to seek work elsewhere. The county is working on new directions for economic development.

From 1963 through 1965, Selma and Dallas County were the sites of a renewed Voting Rights campaign. It was organized by locals of the Dallas County Voters League (DCVL), and joined by activists from Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). In late 1964 they invited help by SCLC leaders. With Martin Luther King, Jr. participating, this campaign attracted national and international news in February and March 1965. They planned a march from Selma to the state capital of Montgomery, Alabama. Two activists were killed during demonstrations before the final march took place.

On March 7, several hundred peaceful marchers were beaten by state troopers and county posse after they passed over the Edmund Pettus Bridge and into the county, intending to march to the state capital of Montgomery. The events were covered by national media. The protesters renewed their walk on March 21, having been joined by thousands of sympathizers from across the country and gained federal protection, to complete the Selma to Montgomery marches.[8] More people joined them, so that some 25,000 people entered Montgomery on the last day of the march. In August of that year, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which was signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson. Millions of African-American citizens across the South have registered and voted in the subsequent years, participating again in the political system.

On March 5, 2018, Selma commemorated these marches. In addition, the city conducted a Community Remembrance Project, unveiling a new historic marker to memorialize the 19 African Americans who were lynched in Dallas County by whites during the late 19th and up to mid-20th century in acts of racial terrorism. This was done in cooperation with the Equal Justice Initiative, which published a report in 2015 that documented nearly 4,000 such lynchings, as well as Selma Center for Nonviolence Truth and Reconciliation at Healing Waters Retreat Center, Selma: Truth, Racial Healing & Transformation, and the Black Belt Community Foundation.[9]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 994 square miles (2,570 km2), of which 979 square miles (2,540 km2) is land and 15 square miles (39 km2) (1.5%) is water.[10]

Adjacent counties

- Chilton County (north)

- Autauga County (northeast)

- Lowndes County (southeast)

- Wilcox County (south)

- Marengo County (west)

- Perry County (northwest)

National protected areas

Transportation

Major highways

Airports

- Craig Field (SEM) in Selma

- Skyharbor Airport (S63) in Selma

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1820 | 6,003 | — | |

| 1830 | 14,017 | 133.5% | |

| 1840 | 25,199 | 79.8% | |

| 1850 | 29,727 | 18.0% | |

| 1860 | 33,625 | 13.1% | |

| 1870 | 40,705 | 21.1% | |

| 1880 | 48,433 | 19.0% | |

| 1890 | 49,350 | 1.9% | |

| 1900 | 54,657 | 10.8% | |

| 1910 | 53,401 | −2.3% | |

| 1920 | 54,697 | 2.4% | |

| 1930 | 55,094 | 0.7% | |

| 1940 | 55,245 | 0.3% | |

| 1950 | 56,270 | 1.9% | |

| 1960 | 56,667 | 0.7% | |

| 1970 | 55,296 | −2.4% | |

| 1980 | 53,981 | −2.4% | |

| 1990 | 48,130 | −10.8% | |

| 2000 | 46,365 | −3.7% | |

| 2010 | 43,820 | −5.5% | |

| Est. 2019 | 37,196 | [11] | −15.1% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[12] 1790–1960[13] 1900–1990[14] 1990–2000[15] 2010–2018[1] | |||

2010

Residents identified by the following ethnicities, according to the 2010 United States Census:

- 69.4% Black

- 29.1% White

- 0.2% Native American

- 0.3% Asian

- 0.0% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

- 0.7% Two or more races

- 0.7% Hispanic or Latino (of any race)

2000

As of the census[16] of 2000, there were 46,365 people, 17,841 households, and 12,488 families residing in the county. The population density was 47 people per square mile (18/km2). There were 20,450 housing units at an average density of 21 per square mile (8/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 63.26% Black or African American, 35.58% White, 0.11% Native American, 0.35% Asian, 0.01% Pacific Islander, 0.14% from other races, and 0.55% from two or more races. 0.63% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 17,841 households, out of which 33.50% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 40.40% were married couples living together, 25.40% had a female householder with no husband present, and 30.00% were non-families. Nearly 27.80% of all households were made up of individuals and 11.60% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.57 and the average family size was 3.15.

In the county, the population was spread out with 28.60% under the age of 18, 9.40% from 18 to 24, 26.20% from 25 to 44, 21.90% from 45 to 64, and 13.90% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females, there were 83.50 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 77.80 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $23,370, and the median income for a family was $29,906. Males had a median income of $31,568 versus $18,683 for females. The per capita income for the county was $13,638. About 27.20% of families and 31.10% of the population were below the poverty line, including 40.70% of those under age 18 and 27.60% of those age 65 or over.

Government and politics

Dallas County is governed by a five-member county commission, elected from single-member districts.

Along with the rest of the Black Belt, Dallas County is solidly Democratic. Although African Americans supported the Republican Party during Reconstruction and into the early 20th century, they have supported Democratic candidates since the national party helped them achieve certain civil rights gains in the mid-1960s. In this same period, most whites in the South have shifted their alliance to the Republican Party. No Republican has carried the county since Richard Nixon’s 3,000-county-plus landslide in 1972.

| Year | GOP | Dem | Others |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 30.8% 5,789 | 68.3% 12,836 | 0.9% 167 |

| 2012 | 30.0% 6,288 | 69.7% 14,612 | 0.3% 64 |

| 2008 | 32.6% 6,798 | 67.1% 13,986 | 0.3% 68 |

| 2004 | 39.5% 7,335 | 60.2% 11,175 | 0.3% 63 |

| 2000 | 39.9% 7,360 | 59.4% 10,967 | 0.7% 137 |

| 1996 | 37.5% 6,612 | 59.5% 10,507 | 3.0% 535 |

| 1992 | 37.7% 7,394 | 56.4% 11,053 | 5.9% 1,157 |

| 1988 | 43.8% 7,630 | 55.4% 9,660 | 0.8% 133 |

| 1984 | 46.3% 9,585 | 52.9% 10,955 | 0.9% 178 |

| 1980 | 42.1% 7,647 | 53.8% 9,770 | 4.0% 730 |

| 1976 | 43.7% 7,144 | 54.2% 8,866 | 2.2% 351 |

| 1972 | 60.5% 8,644 | 38.0% 5,427 | 1.5% 209 |

| 1968 | 7.5% 1,246 | 39.2% 6,516 | 53.4% 8,874 |

| 1964 | 89.1% 5,888 | 10.9% 719 | |

| 1960 | 56.9% 2,872 | 41.7% 2,103 | 1.4% 69 |

| 1956 | 43.4% 2,324 | 39.6% 2,121 | 17.0% 913 |

| 1952 | 55.1% 2,550 | 45.0% 2,082 | 0.0% 0 |

| 1948 | 4.6% 132 | 95.4% 2,738 | |

| 1944 | 4.9% 149 | 94.7% 2,883 | 0.4% 11 |

| 1940 | 4.8% 157 | 95.1% 3,106 | 0.1% 3 |

| 1936 | 1.5% 49 | 98.4% 3,205 | 0.1% 4 |

| 1932 | 3.0% 93 | 96.6% 3,027 | 0.4% 13 |

| 1928 | 27.0% 705 | 73.0% 1,905 | 0.0% 1 |

| 1924 | 2.4% 50 | 91.8% 1,948 | 5.9% 125 |

| 1920 | 2.8% 78 | 97.2% 2,702 | 0.0% 0 |

| 1916 | 1.4% 23 | 97.9% 1,565 | 0.7% 11 |

| 1912 | 1.1% 16 | 96.7% 1,461 | 2.3% 34 |

| 1908 | 1.9% 28 | 97.1% 1,420 | 1.0% 15 |

| 1904 | 2.4% 36 | 96.7% 1,472 | 1.0% 15 |

Education

Areas not in Selma are served by Dallas County Schools, while areas in Selma are served by Selma City Schools.

Communities

Cities

- Selma (county seat)

- Valley Grande

Towns

Census-designated places

Unincorporated communities

Ghost town

Notable Residents

- Kenneth D. McKellar, American Politician from Tennessee

Notable inhabitants

- Redoshi, a woman originally from Benin, West-Africa, kidnapped and sold to a Dallas County slave owner.

See also

References

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 11, 2014. Retrieved May 16, 2014.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- Fitts, Alston (2017). Selma: A Bicentennial History. University of Alabama Press. pp. 12–14. ISBN 9780817319328.

- Forner, Karlyn (2017). Why the Vote Wasn’t Enough for Selma. Duke UP. p. 35.

- Daley, Jason (April 5, 2019). "Researcher Identifies the Last Living Survivor of the Transatlantic Slave Trade". Smithsonian. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- "Lynching in America/Supplement: Lynchings by County, 3rd edition, Equal Justice Initiative, 2017" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-10-23. Retrieved 2018-04-13.

- Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror, 2015, Equal Justice Institute, Montgomery, Alabama

- Gary May, Bending Toward Justice: The Voting Rights Act and the Transformation of American Democracy (Basic Books, 2013)

- "Selma, Alabama Memorializes Lynching Victims", Equal Justice Initiative News, 05 March 2018; Accessed 13 April 2018

- "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

- Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 24, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". Retrieved November 15, 2016.

External links

- Dallas County map of roads/towns (map © 2007 Univ. of Alabama).