Zakarid Armenia

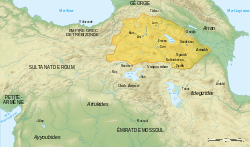

Zakarid Armenia[3] (Armenian: Զաքարյան Հայաստան Zakaryan Hayastan), was an Armenian principality between 1201 and 1360, ruled by the Zakarid-Mkhargrzeli dynasty. The city of Ani was the capital of the princedom. The Zakarids were vassals to the Bagrationi dynasty in Georgia, but frequently acted independently and at times titled themselves as kings.[4][5] In 1236, they became vassals to the Mongol Empire.[6] Their descendants continued to hold Ani until the 1330s, when they lost it to a succession of Turkish dynasties, including the Kara Koyunlu, who made Ani their capital.

Zakarid Armenia Զաքարյան Հայաստան | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1201–1360 | |||||||||||

Zakarid territories in the early 13th century[2] | |||||||||||

| Capital | Ani | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Armenian | ||||||||||

| Religion | Armenian Apostolic | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Zakarids | |||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||

• Established | 1201 | ||||||||||

• Conquered by Ilkhanate | 1360 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

History

Following the collapse of the Bagratuni Dynasty of Armenia in 1045, Armenia was successively occupied by Byzantines and, following the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, by the Seljuks.[7] Khosrov, the first historically traceable member of the Zakarid family, moved from Armenia to southern Georgia during the Seljuk invasions in the early 11th century. Over the next hundred years, the Zakarids gradually gained prominence at the Georgian court, where they became known as Mkhargrdzeli (Long-shoulder) or in Armenian: Երկայնաբազուկ, (Yerkaynabazuk). A family legend says that this name was a reference to their Achaemenid ancestor Artaxerxes II the "Longarmed" (404–358 BC).[8][9]

During the 12th century, the Bagratids of Georgia enjoyed a resurgence in power, and managed to expand into Muslim occupied Armenia.[10] The former Armenian capital Ani would be captured five times between 1124 and 1209.[11] Under King George III of Georgia, Sargis Zakarian was appointed as governor of Ani in 1161. In 1177, the Zakarids supported the monarchy against the insurgents during the rebellion of Prince Demna and the Orbeli family. The uprising was suppressed, and George III persecuted his opponents and elevated the Zakarids.

Despite some complications in the reign of George III, the successes continued in the reign of the Queen Tamar.[10] This was chiefly due to the Armenian generals Zakare and Ivane.[12][13] Around the year 1199, they retook the city of Ani, and in 1201, Ani became the capital of Zakarid Armenia.[10] Armenia was often governed as an independent state by the Zakarians.[4] The volume of trade seems to have increased in the early 13th century, and under the Zakarid princes the city prospered, at least until the area was occupied by the Mongols in 1237. The Zakarians amassed a great fortune, governing all of northern Armenia; Zakare and his descendants ruled in northwestern Armenia with Ani as their capital, while Ivane and his offspring ruled eastern Armenia, including the city of Dvin. Eventually, their territories came to resemble those of Bagratid Armenia.[7]

Zakare and Ivane commanded the Georgian-Armenian armies for almost three decades, achieving major victories at Shamkor in 1195 and Basian in 1203 and leading raids into northern Persia in 1210.

When the Khwarezms invaded the region, Dvin was ruled by the aging Ivane, who had given Ani to his nephew Shahnshah, son of Zakare. Dvin was lost, but Kars and Ani did not surrender.[10]

However, when Mongols took Ani in 1236, they had a friendly attitude towards the Zakarids.[10] They confirmed Shanshe in his fief, and even added to it the fief of Avag, son of Ivane. Further, in 1243, they gave Akhlat to the princess T’amt’a, daughter of Ivane.[10]

After the Mongols captured Ani in 1236, the Zakarids ruled not as vassals of the Bagratids, but rather the Mongols.[7] The later kings of Zakarids continued their control over Ani until the 1360, when they lost to the Kara Koyunlu Turkoman tribes, who made Ani their capital.[7]

References

- George A. Bournoutian «A Concise History of the Armenian People», map 19. Mazda Publishers, Inc. Costa Mesa California 2006

- George A. Bournoutian «A Concise History of the Armenian People», map 19. Mazda Publishers, Inc. Costa Mesa California 2006

- Chahin, Mack (2001). The Kingdom of Armenia: A History (2. rev. ed.). Richmond: Curzon. p. 235. ISBN 0700714529.

- Strayer, Joseph (1982). Dictionary of the Middle Ages. 1. p. 485.

The degree of Armenian dependence on Georgia during this period is still the subject of considerable controversy. The numerous Zak'arid inscriptions leave no doubt that they considered themselves Armenians, and they often acted independently.

- Eastmond, Antony (2017). Tamta's World. Cambridge University Press. p. 26.

In one inscription on the palace church on the citadel of Ani, the brothers' principal city and the former capital of Armenia, they refer to themselves as 'the kings of Ani', suggesting loftier ambitions, independent of Georgia, and in the inscription at Haghartsin quoted in the first chapter, they claimed descent from the Bagratunis, the Armenian kings of the region until the eleventh century.

- Suny, Ronald Grigor (1994). The Making of the Georgian Nation. Indiana University Press. p. 40. ISBN 0-253-20915-3.

Within the kingdom, the Zakharian-Mkhargrdzelis and the Orbelianis, "both families which were Armenian in religion and not Georgian by origin, represented a definite revival and assertion of Armenian influence throughout the eastern provinces of the kingdom."

- Sim, Steven. "The City of Ani: A Very Brief History". VirtualANI. Retrieved 2007-07-15.

- Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia, 3th volume

- Paul Adalian, Rouben (2010). Historical Dictionary of Armenia. p. 83.

- Minorsky, Vladimir (1953). Studies in Caucasian History. New York: Taylor’s Foreign Press. pp. 102–103. ISBN 978-0-521-05735-6.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911), , Encyclopædia Britannica, 2 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 47

- http://www.aina.org/reports/tykaaog.pdf

- Suny (1994), p. 39.