Colonial period of South Carolina

The history of the colonial period of South Carolina focuses on the English colonization that created one of the original Thirteen Colonies. Major settlement began after 1651 as the northern half of the British colony of Carolina attracted frontiersmen from Pennsylvania and Virginia, while the southern parts were populated by wealthy English people who set up large plantations dependent on slave labor, for the cultivation of cotton, rice, and indigo.

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of South Carolina | ||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

The colony was separated into the Province of South Carolina and the Province of North Carolina in 1712. South Carolina's capital city of Charleston became a major port for traffic on the Atlantic Ocean, and South Carolina developed indigo, rice and Sea Island cotton as commodity crop exports, making it one of the most prosperous of the colonies. A strong colonial government fought wars with the local Indians, and with Spanish imperial outposts in Florida, while fending off the threat of pirates. Birth rates were high, food was abundant, and these offset the disease environment of malaria to produce rapid population growth among whites. With the expansion of plantation agriculture, the colony imported numerous African slaves, who comprised a majority of the population by 1708. They were integral to its development.

The colony developed a system of laws and self-government and a growing commitment to Republicanism, which patriots feared was threatened by the British Empire after 1765. At the same time, men with close commercial and political ties to Great Britain tended to be Loyalists when the revolution broke out. South Carolina joined the American Revolution in 1775, but was bitterly divided between Patriots and Loyalists. The British invaded in 1780 and captured most of the state, but were finally driven out.

Overview

The first European contact with the Carolinas was an expedition led by Pedro de Salazar from Santo Domingo which arrived between northern Georgia and Cape Fear between August 1514 and December 1516. It enslaved 500 Native Americans. Most died on the return trip to Santo Domingo. The rest were divided among investors in the expedition and crew, and died soon after arriving.[1][2][3] The next contact was a 1521 trip led by Pedro de Quejo and Francisco Gordillo, which enslaved 60 Native Americans in Winyah Bay.[2][3] De Quejo returned in 1525 and explored from Amelia Island, Florida to Chesapeake Bay, Maryland.[2][3] He captured more Native Americans to use as interpreters, and his findings and place names were published on a 1526 map by Juan Vespucci.[2] In 1526 Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón returned to Winyah Bay to found a colony, but after a month moved to San Miguel de Gualdape in what is now Georgia;[2] Spanish coins, beads and a bullet have been found near the Georgia settlement.[3]

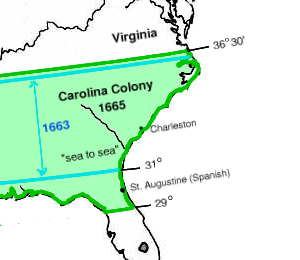

After several expeditions and a settlement attempted in the 16th century, France and Italy had abandoned the area of present-day South Carolina. In 1629, Charles I of England granted his attorney general a charter to everything between latitudes 36 and 31. Later, in 1663, Charles II of England granted the land to eight Lords Proprietors in return for their financial and political assistance in restoring him to the throne in 1660.[4] Anthony Ashley Cooper, later the 1st Earl of Shaftesbury emerged as the leader of the Lords Proprietors, and John Locke became his assistant and chief planner. The two men were chiefly responsible for developing the Grand Model for the Province of Carolina, which included the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina.[5]

The newly created province was intended in part to serve as an English bulwark to contest lands claimed by Spanish Florida.[6][7] There was a single government of the Carolinas based in Charleston until 1712, when a separate government (under the Lords Proprietors) was set up for North Carolina. In 1719, the Crown purchased the South Carolina colony from the absentee Lords Proprietors and appointed Royal Governors. By 1729, seven of the eight Lords Proprietors had sold their interests back to the Crown; the separate royal colonies of North Carolina and South Carolina were established.[8]

Throughout the Colonial Period, the Carolinas participated in numerous wars with the Spanish and the Native Americans, particularly the Yamasee, Apalachee, and Cherokee. During the Yamasee War of 1715–1717, South Carolina faced near annihilation due to Native American attacks. An indigenous alliance had formed to try to push the colonists out, in part as a reaction to their trade in Native American slaves for the nearly 50 years since 1670. The effects of the slave trade affected tribes throughout the Southeast. Estimates are that Carolinians exported 24,000-51,000 Native American slaves to markets from Boston to Barbados.[9]

The emerging planter class used the revenues to finance the purchase of enslaved Africans and financing of indentured servants. So many Africans were imported that they comprised a majority of the population in the colony from 1708 through the American Revolution. Living and working together on large plantations, they developed what is known as the Gullah culture and creole language, maintaining many west African traditions of various cultures, while adapting to the new environment.

The Black population of the Lowcountry was dominated by wealthy planters of English descent and indentured servants from southern and western England. The interior Carolina upcountry was settled later, largely in the 18th century by Ulster Scots immigrants arriving via Pennsylvania and Virginia, German Calvinists, French Huguenot refugees in the Piedmont and foothills as well as by working class English indentured servants who moved inland after completing their terms of service working on coastal plantations. Toward the end of the Colonial Period, the upcountry people were underrepresented politically and felt they were mistreated by the planter elite. In reaction, many took a Loyalist position when the Lowcountry planters complained of the new taxes, an issue that later contributed to the colony's support of the American Revolution.

In North Carolina a short-lived colony was established near the mouth of the Cape Fear River. A ship was sent southward to explore the Port Royal, South Carolina area, where the French had established the short-lived Charlesfort post and the Spanish had built Santa Elena, the capital of Spanish Florida from 1566 to 1587, until it was abandoned. Captain Robert Sanford made a visit with the friendly Edisto Indians. When the ship departed to return to Cape Fear, Dr. Henry Woodward stayed behind to study the interior and native Indians.

In Bermuda, Colonel William Sayle, an 80-year-old Puritan Bermudian colonist, was named governor of Carolina. On March 15, 1670, under Sayle (who sailed on a Bermuda sloop with a number of Bermudian families), they finally reached Port Royal. According to the account of one passenger, the Indians were friendly, made signs toward where they should land, and spoke broken Spanish. Spain still considered Carolina to be its land; the main Spanish base, St. Augustine, was not far away. The Spanish missionary provinces of Guale and Mocama occupied the coast south of the Savannah River and Port Royal.

Although the Edisto Indians were not happy to have the English settle permanently, the chief of the Kiawah Indians, who lived farther north along the coast, arrived to invite the English to settle among his people and protect them from the Westo tribe, slave-raiding allies of Virginia. The sailors agreed and sailed for the region now called West Ashley. When they landed in early April at Albemarle Point on the shores of the Ashley River, they founded Charles Town, named in honor of their king. On May 23, Three Brothers arrived in Charles Town Bay without 11 or 12 passengers who had gone for water and supplies at St. Catherines Island, and had run into Indians allied with the Spanish. Of the hundreds of people who had sailed from England or Barbados, only 148 people, including three African slaves, lived to arrive at Charles Town Landing.[10]

Monarchs

| Name Reign |

Portrait | Arms | Birth | Marriage(s) Issue |

Death | Claim | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charles II 1663 – 6 February 1685[11] Recognised by Royalists in 1649 (24 years, 253 days) |

|

.svg.png) |

29 May 1630 (N.S. 8 June 1630) St James's Palace Son of Charles I and Henrietta Maria of France |

Catherine of Braganza Portsmouth 21 May 1662 No children |

6 February 1685 Whitehall Palace Aged 54 |

Son of Charles I (cognatic primogeniture / English Restoration) | |

| James VII & II 6 February 1685 – 23 December 1688 (deposed) (3 years, 321 days) |

.jpg) |

.svg.png) |

14 October 1633 (N.S. 24 October 1633) St James's Palace Son of Charles I and Henrietta Maria of France |

(1) Anne Hyde The Strand 3 September 1660 8 children (2) Mary of Modena Dover 21 November 1673 7 children |

16 September 1701 Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye Aged 67 |

Son of Charles I (cognatic primogeniture) | |

| Mary II 13 February 1689 – 28 December 1694 (5 years, 318 days) |

|

.svg.png) |

30 April 1662 (N.S. 10 May 1662) St James's Palace Daughter of James II and Anne Hyde |

St James's Palace 4 November 1677 No children |

28 December 1694 Kensington Palace Aged 32 |

Daughter and son-in-law of James VII & II and Grandchildren of Charles I (offered the crown by Parliament) | |

| William III William of Orange 13 February 1689 – 8 March 1702 (13 years, 23 days) |

.jpg) |

.svg.png) |

4 November 1650 (N.S. 14 November 1650) The Hague Son of William II, Prince of Orange and Mary, Princess Royal[12] |

8 March 1702 Kensington Palace Aged 51 after breaking his collarbone from falling off his horse | |||

| Anne 8 March 1702 – 1 May 1707[13] (5 years, 54 days) Queen of Great Britain and Ireland (from 1707) |

|

.svg.png) |

6 February 1665 St James's Palace Daughter of James II and Anne Hyde |

George of Denmark St James's Palace 28 July 1683 17 pregnancies no surviving children |

1 August 1714 Kensington Palace Aged 49 |

Daughter of James II (cognatic primogeniture / Bill of Rights 1689) | |

| Anne 1 May 1707 – 1 August 1714 (7 years, 92 days) |

|

.svg.png) |

6 February 1665 St James's Palace Daughter of James II and VII and Anne Hyde |

George of Denmark St James's Palace 28 July 1683 17 pregnancies no surviving children |

1 August 1714 Kensington Palace Aged 49 |

Daughter of James II and VII (cognatic primogeniture / Bill of Rights 1689) | |

| George I George Louis 1 August 1714 – 11 June 1727 (12 years, 314 days) |

|

.svg.png) |

28 May 1660 (N.S. 7 June 1660) Leineschloss Son of Ernest Augustus, Elector of Brunswick-Lüneburg and Sophia of Hanover |

Sophia Dorothea of Brunswick-Lüneburg-Celle 21 November 1682 2 children |

11 June 1727 Osnabrück Aged 67 |

Great-grandson of James VI and I (Act of Settlement / eldest son of Sophia of Hanover) | [14] |

| George II George Augustus 11 June 1727 – 25 October 1760 (33 years, 136 days) |

|

.svg.png) |

30 October 1683 (N.S. 9 November 1683) Herrenhausen Son of George I and Sophia Dorothea of Brunswick-Lüneburg-Celle |

Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach 22 August 1705 8 children |

25 October 1760 Kensington Palace Aged 76 |

Son of George I | [15] |

| George III George William Frederick 25 October 1760 – July 4, 1776 (59 years, 96 days) Monarchy Abolished |

|

.svg.png) |

4 June 1738 Norfolk House Son of Frederick, Prince of Wales and Princess Augusta of Saxe-Gotha |

Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz St James's Palace 8 September 1761 15 children |

29 January 1820 Windsor Castle Aged 81 |

Grandson of George II | [16] |

The end of proprietary rule

Proprietary rule was unpopular in South Carolina almost from the start, mainly because propertied immigrants to the colony hoped to monopolize the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina as a basis for government. Moreover, many Anglicans resented the Proprietors' guarantee of freedom of religion to Dissenters. In November 1719, Carolina elected James Moore as governor and sent a representative to ask the King to make Carolina a royal province with a royal governor. They wanted the Crown to grant the colony aid and security directly from the English government. Because the Crown was interested in Carolina's exports and did not think the Lords Proprietor were adequately protecting the colony, it agreed. Robert Johnson, the last proprietary governor, became the first royal governor.[17]

Meanwhile, the colony of Carolina was slowly splitting in two. In the first fifty years of the colony's existence, most settlement was focused on the region around Charleston, as the northern part of the colony had no deep water port. North Carolina's earliest settlement region, the Albemarle Settlements, was colonized by Virginians and closely tied to Virginia. In 1712, the northern half of Carolina was granted its own governor and named "North Carolina". North Carolina remained under proprietary rule until 1729.

Because South Carolina was more populous and more commercially important, most Europeans thought primarily of it, and not of North Carolina, when they referred to "Carolina". By the time of the American Revolution, this colony was known as "South Carolina."

Frontier settlement

Governor Robert Johnson encouraged settlement in the western frontier to make Charles Town's shipping more profitable, and to create a buffer zone against attacks. The Carolinians arranged a fund to lure European Protestants. Each family would receive free land based on the number of people that it brought over, including indentured servants and slaves. Every 100 families settling together would be declared a parish and given two representatives in the state assembly. Within ten years, eight townships formed, all along navigable streams. Charlestonians considered the towns created by the Huguenots, German Calvinists, Scots, Ulster-Scots Presbyterians, working class English laborers who were former indentured servants and Welsh farmers, such as Orangeburg and Saxe-Gotha (later called Cayce), to be their first line of defense in case of an Indian attack, and military reserves against the threat of a slave uprising. Between 1729 and 1775, twenty-nine new towns were founded in South Carolina.[18]

By the 1750s the Piedmont region attracted numerous frontier families from the north, using the Great Wagon Road. Differences in religion, philosophy and background between the mostly subsistence farmers in the Upcountry and the slaveholding planters of the Low Country bred distrust and hostility between the two regions. The Low Country planters traditionally had wealth, education and political power. By the time of the Revolution, however, the Upcountry contained nearly half the white population of South Carolina, about 30,000 settlers. Nearly all of them were Dissenting Protestants. After the Revolution, the state legislature disestablished the Anglican Church.[19]

The main source of wealth during the late-colonial period was the export of rice, deerskins and, by the 1760s, indigo. Sea Island cotton, produced on large plantations off the coast, was also highly profitable.

Cherokee Wars

Although Governor Francis Nicholson attempted to pacify the Cherokee with gifts, they had grown discontented with the arrangements. Sir Alexander Cuming negotiated with them to open some land for settlement in 1730. Because Governor James Glen stepped in to bring peace between the Creek people and Cherokee, who were traditional enemies, the Cherokee rewarded him by granting South Carolina a few thousand acres of land near their major Lower Town of Keowee. In 1753, the Carolinians built Fort Prince George as a British outpost and trading center near the Keowee River. Two years later Old Hop, an important Cherokee chief, made a treaty with Glen at Saluda Old Town, midway between Charles Town and Keowee. Old Hop gave the Carolinians the 96th District, a region that included parts of ten currently separate counties.

From 1755 to 1758, Cherokee warriors served as British allies in campaigns along the Virginia and Pennsylvania frontier. Returning homeward, they were killed by Virginia frontiersmen. In 1759, the Cherokee avenged these killings and began attacking white settlers in the southern colonial Upcountry. South Carolina's Governor William Henry Lyttelton raised an army of 1,100 men and marched on the Lower Towns, which quickly agreed to peace. As part of the peace terms, two dozen Cherokee chiefs were imprisoned as hostages in Fort Prince George. Lyttelton returned to Charles Town, but the Cherokee continued raiding the frontier. In February 1760, the Cherokee attacked Fort Prince George trying to rescue the hostages. In the battle, the fort's commander was killed. His replacement quickly ordered the execution of the hostages, then fought off the Cherokee assault.[20]

Unable to put down the rebellion, Governor Lyttelton appealed to Jeffrey Amherst, who sent Archibald Montgomery with an army of 1,200 British regulars and Scots Highlanders. Montgomery's army burned a few of the Cherokees' abandoned Lower Towns. When he tried to cross into the region of the Cherokee Middle Towns, he was ambushed and defeated at "Etchoe Pass" and forced to return to Charles Town. In 1761, the British made a third attempt to defeat the Cherokee. General Grant led an army of 2,600 men, including Catawba scouts. The Cherokee fought at Etchoe Pass but failed to stop Grant's army. The British burned the Cherokee Middle Towns and fields of crops.[21]

In September 1761, a number of Cherokee chiefs led by Attakullakulla petitioned for peace. The terms of the peace treaty, concluded in Charleston that December, included the cession of lands along the South Carolina frontier.[22]

Settlement of Upcountry

After the Cherokee defeat and cession of land, new settlers from Ulster flooded into the Upcountry through the Waxhaws in what is now called Lancaster County. Lawlessness ensued and robbery, arson, and looting became common. Upcountry residents formed a group of "Regulators," vigilantes who took the law into their own hands to control the criminals. Having acquired 50% of the state's white population, but just three elected assemblymen in the Commons House of Assembly, the Upcountry sent representative Patrick Calhoun and other representatives before the Charles Town state legislature to appeal for representation, courts, roads, and supplies for churches and schools. Before long, Calhoun and Moses Kirkland were in the legislature as Upcountry representatives.[23]

By 1775, the colony contained 60,000 European Americans and 80,000 mostly enslaved African Americans.

Lord William Campbell was the last English Governor of the Province of South Carolina.

Religion

Numerous churches built bases in Charleston, and expanded into the rural areas. From the founding of Charleston onwards, the colony welcomed many different religious groups, including Jews and Quakers, but Catholics were prohibited from practicing until after the American Revolution.[24] Baptists and Methodists increased in number rapidly in the late 18th century as a result of the Great Awakening and its revivals, and their missionaries attracted many slaves with their inclusive congregations and recognition of blacks as preachers. The Scots-Irish in the Backcountry were Presbyterians, and the wealthy planters in the Low Country tended to be English Anglicans. The different churches recognized and supported each other, eventually building the colony into a pluralist and tolerant society.[25] Despite official religious tolerance, tensions did exist between Anglican and 'Dissenter' factions throughout the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.

The highly successful preaching tour of evangelist George Whitefield in 1740 ignited a religious revival—called the First Great Awakening—which energized evangelical Protestants. They expanded their membership among the white farmers, and women were especially active in the small Methodist and Baptist[26] churches that were springing up everywhere.[27] The evangelicals worked hard to convert the slaves to Christianity and were especially successful among black women, who had played the role of religious specialists in Africa and again in America. Slave women exercised wide-ranging spiritual leadership among Africans in America in healing and medicine, church discipline, and revival enthusiasm.[28]

African slaves

Many of the rich planters came from Barbados and other islands in the Caribbean, and brought seasoned African slaves from there. The planters duplicated elements of the Caribbean economies, developing plantations for the cultivation of export crops, such as Sea Island cotton, indigo, and particularly rice. The slaves came from many diverse cultures in West Africa, where they had developed an immunity to endemic malaria, which helped them survive in the Low Country of South Carolina, where it frequently occurred. Peter Wood documents that "Negro slaves played a significant and often determinative part in the evolution of the colony."[29] They were integral to the expansion of the rice culture, and were also important in timber harvesting, as coopers, and in the production of naval stores. They were also active in the fur trade, and as boatmen, fishermen and cattle herders.[29]

By 1708, expansion of plantation agriculture had required continuing importation of slaves from Africa and they comprised a majority of the population in the colony, a status maintained after the colonial era.[30] On the large rice and cotton plantations, where slaves were held in large numbers with few white overseers, they gradually developed what has become known as the Gullah culture, which preserved numerous African customs and practices within adaptations to the local environment, and they developed a creole language based on West African languages and English.

Colonists tried to regulate the numerous slaves, including establishing dress rules to maintain differences between the classes. Relations between colonists and slaves were a result of continuing negotiation, with increasing tensions as slaves sought freedoms. In 1739, a group of slaves rose up in the Stono rebellion. Some of the leaders were from the Catholic kingdom of Kongo and appeared to be seasoned warriors; they introduced ritual practices from there and appeared to use military tactics they had learned in the Kongo.[31] The site of the Stono Rebellion was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1974, in recognition of the slaves' bid for freedom.[29]

The comprehensive Negro Act of 1740 was passed in South Carolina, during Governor William Bull's time in office, in response to the Stono Rebellion in 1739.[32] The act made it illegal for enslaved Africans to move abroad, assemble in groups, raise food, earn money, and learn to write (though reading was not proscribed). Additionally, owners were permitted to kill rebellious slaves if necessary.[33] The Act remained in effect until 1865.[34]

Hurricanes

South Carolina was struck by four major hurricanes during the colonial period. Colonists became constantly aware of the threat these storms posed and their effects even on warfare.[35]

The 1752 hurricane caused massive damage to homes, businesses, shipping, outlying plantation buildings and the rice crop; about 95 people died. Charles Town, the capital, was the fifth-largest city in British North America at the time. The storm was compact and powerful; the city and surrounding areas were saved from even greater destruction only because the wind shifted some three hours before high tide. The destruction resulted in a series of political effects that together substantially weakened the relationship between the royal governor and the local political elites in the Commons House Assembly: there was bickering between the various political authorities over money for rebuilding following the destruction of the colony's defenses, and the disruption caused a devastating financial crisis. The Commons threatened to report

References

- Hoffman, Paul E. (1980). "A New Voyage of North American Discovery: Pedro de Salazar's Visit to the "Island of Giants"". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 58 (4): 415–426. ISSN 0015-4113.

- Peck, Douglas T. (2001). "Lucas Vásquez de Ayllón's Doomed Colony of San Miguel de Gualdape". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. 85 (2): 183–198. ISSN 0016-8297.

- Milanich, Jerald T. (2018). Florida Indians and the Invasion from Europe. Gainesville: Library Press at UF. ISBN 978-1-947372-45-0. OCLC 1021804892.

- Danforth Prince (10 March 2011). Frommer's The Carolinas and Georgia. John Wiley & Sons. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-118-03341-8.

- Wilson, Thomas D. The Ashley Cooper Plan: The Founding of Carolina and the Origins of Southern Political Culture. Chapter 1.

- Peter Charles Hoffer (14 December 2006). The Brave New World: A History of Early America. JHU Press. p. 323. ISBN 978-0-8018-8483-2.

- Matricia Riles Dickman (2 March 1999). The Tree that Bends: Discourse, Power, and the Survival of Maskoki People. University of Alabama Press. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-8173-0966-4.

- Walter B. Edgar (1998). South Carolina: A History. Univ of South Carolina Press.

- Joseph Hall, "The Great Indian Slave Caper", review of Alan Gallay, The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South, 1670-1717, Common-place, vol. 3, no. 1 (October 2002), accessed 5 March 2017.

- Richard Waterhouse (2005). A New World Gentry: The Making of a Merchant and Planter Class in South Carolina, 1670-1770. The History Press. p. 27.

- "Oliver Cromwell (1649–1658 AD)". Archived from the original on 2008-11-21. Retrieved 2018-01-12.

- "WILLIAM III - Archontology.org". Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- "Anne (England) - Archontology.org". Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- "George I". royal.gov.uk. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- "George II". royal.gov.uk. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- "George III". royal.gov.uk. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- Alexia Jones Helsley; Lawrence S. Rowland (2005). Beaufort, South Carolina: A History. The History Press. p. 38.

- J.D. Lewis, "The Royal Colony of South Carolina," accessed 5 March 2017.

- David Hackett Fischer (1991). Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America. Oxford University Press. p. 64.

- Daniel J. Tortora (2015). Carolina in Crisis: Cherokees, Colonists, and Slaves in the American Southeast, 1756-1763. University of North Carolina Press.

- Spencer C. Tucker (2011). The Encyclopedia of North American Indian Wars, 1607–1890: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 157.

- John Oliphant (2001). Peace and War on the Anglo-Cherokee Frontier, 1756-63. Louisiana State U.P. p. 243.

- Edward McCrady (1899). The History of South Carolina Under the Royal Government, 1719-1776. Macmillan. p. 23.

- Walter Edgar, "South Carolina: A History." Columbia, University of South Carolina Press 1988, pp. 181-84.

- Charles H. Lippy, "Chastized by Scorpions: Christianity and Culture in Colonial South Carolina, 1669-1740," Church History, vol. 79, no. 2 (June 2010), pp. 253-70.

- J. Glen Clayton, "South Carolina Baptist Records," South Carolina Historical Magazine, vol. 85, no. 4 (October 1984), pp. 319-27.

- David T. Morgan, Jr., "The Great Awakening in South Carolina, 1740-1775," South Atlantic Quarterly, (1971), pp. 595-606.

- Sylvia R. Frey and Betty Wood, Come Shouting to Zion: African American Protestantism in the American South and British Caribbean to 1830 (1998)

- Benjamin Quarles, "Review: Peter H. Wood, Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 Through the Stono Rebellion (1974)", Journal of Negro History, vol. 60, no. 2 (April 1975), pp. 332-34.

- Wood, Peter H. Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 Through the Stono Rebellion (1996)

- John K. Thornton, "African Dimensions Of The Stono Rebellion," American Historical Review, vol. 96, no. 4 (October 1991), pp. 1101-13.

- Konadu, Kwasi (2010-05-12). The Akan Diaspora in the Americas. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199745388.

- "Slavery and the Making of America . Timeline | PBS". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 2017-10-09.

- Gabbatt, Adam (24 October 2017). "A sign on scrubland marks one of America's largest slave uprisings. Is this how to remember black heroes?". Guardian US. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- Jonathan Mercantini, "The great Carolina hurricane of 1752," South Carolina Historical Magazine, vol. 103, no. 4 (October 2002), pp. 351-65.

Bibliography

- Edgar, Walter. South Carolina: A History, (1998) the standard scholarly history

- Edgar, Walter, ed. The South Carolina Encyclopedia, University of South Carolina Press, (2006), ISBN 1-57003-598-9, the most comprehensive scholarly guide

- Rogers Jr., George C. and C. James Taylor. A South Carolina Chronology, 1497-1992 2nd Ed. (1994)

- Wallace, David Duncan. South Carolina: A Short History, 1520-1948 (1951) standard scholarly history

- Clarke, Erskine. Our Southern Zion: A History of Calvinism in the South Carolina Low Country, 1690-1990 (1996)

- Coclanis, Peter A., "Global Perspectives on the Early Economic History of South Carolina," South Carolina Historical Magazine, 106 (April–July 2005), 130–46.

- Crane, Verner W. The Southern Frontier, 1670-1732 (1956)

- Johnson Jr., George Lloyd. The Frontier in the Colonial South: South Carolina Backcountry, 1736-1800 (1997)

- Edelson, S. Max. Plantation Enterprise in Colonial South Carolina (2007)

- Hewat, Alexander. An Historical Account of the Rise and Progress of the Colonies of South Carolina and Georgia Vol.1 and Vol.2 (London 1779)

- LeMaster, Michelle, ed. Creating and Contesting Carolina. Proprietary Era Histories, (2013)

- Nagl, Dominik. No Part of the Mother Country, but Distinct Dominions - Law, State Formation and Governance in England, Massachusetts and South Carolina, 1630-1769 (2013)

- Rogers, George C. Evolution of a Federalist: William Loughton Smith of Charleston (1758-1812) (1962)

- Roper, L. H. Conceiving Carolina: Proprietors, Planters, and Plots, 1662-1729 (2004), ISBN 1-4039-6479-3.

- Smith, Warren B. White Servitude in Colonial South Carolina (1961)

- Tortora, Daniel J. Carolina in Crisis: Cherokees, Colonists, and Slaves in the American Southeast, 1756–1763 (2015), ISBN 1-469-62122-3.

- Wilson, Thomas D. The Ashley Cooper Plan: The Founding of Carolina and the Origins of Southern Political Culture. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

- Wood, Peter H. Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 Through the Stono Rebellion (1996)

- Wright, Louis B. South Carolina: A Bicentennial History' (1976)