Yellow Emperor

The Yellow Emperor, also known as the Yellow Thearch, or by his Chinese name Huangdi (/ˈhwɑːŋ ˈdiː/),[2] is a deity (shen) in Chinese religion, one of the legendary Chinese sovereigns and culture heroes included among the mytho-historical Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors and cosmological Five Forms of the Highest Deity (Chinese: 五方上帝; pinyin: Wǔfāng Shàngdì).[3][note 1] Calculated by Jesuit missionaries on the basis of Chinese chronicles and later accepted by the twentieth-century promoters of a universal calendar starting with the Yellow Emperor, Huangdi's traditional reign dates are 2697–2597 or 2698–2598 BCE.

| Yellow Emperor 黃帝 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One of Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors | |||||

| |||||

| Reign | 2698–2598 BCE (mythical) | ||||

| Born | 2711 BCE | ||||

| Died | 2598 BCE (aged 113) | ||||

| Spouse | Leizu Fenglei Tongyu Momu | ||||

| Issue | Shao Hao Chang Yi(昌意), father of Zhuan Xu | ||||

| |||||

| Father | Shaodian | ||||

| Mother | Fubao | ||||

| Huangdi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

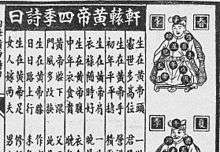

As depicted by Gan Bozong, woodcut print, Tang dynasty (618-907) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 黃帝 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 黄帝 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Yellow Emperor" "Yellow Thearch" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Taoism |

|---|

|

|

Practices

|

|

Deities |

|

Organisations |

Huangdi's cult became prominent in the late Warring States and early Han dynasty, when he was portrayed as the originator of the centralized state, as a cosmic ruler, and as a patron of esoteric arts. A large number of texts – such as the Huangdi Neijing, a medical classic, and the Huangdi Sijing, a group of political treatises – were thus attributed to him. Having waned in influence during most of the imperial period, in the early twentieth century Huangdi became a rallying figure for Han Chinese attempts to overthrow the rule of the Qing dynasty, which they considered foreign because its emperors were Manchu people. To this day the Yellow Emperor remains a powerful symbol within Chinese nationalism.

Traditionally credited with numerous inventions and innovations – ranging from the Chinese calendar to an ancestor of football – the Yellow Emperor is now regarded as the initiator of Chinese culture,[4] and said to be the ancestor of all Chinese.[5]

Names

"Huangdi": Yellow Emperor, Yellow Thearch

Until 221 BCE when Qin Shi Huang of the Qin dynasty coined the title huangdi (皇帝) – conventionally translated as "emperor" – to refer to himself, the character di 帝 did not refer to earthly rulers but to the highest god of the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE) pantheon.[6] In the Warring States period (c. 475–221 BCE), the term di on its own could also refer to the deities associated with the five Sacred Mountains of China and colors. Huangdi (黃帝), the "yellow di", was one of the latter. To emphasize the religious meaning of di in pre-imperial times, historians of early China commonly translate the god's name as "Yellow Thearch" and the first emperor's title as "August Thearch", in which "thearch" refers to a godly ruler.[7]

In the late Warring States period, the Yellow Emperor was integrated into the cosmological scheme of the Five Phases, in which the color yellow represents the earth phase, the Yellow Dragon, and the center.[8] The correlation of the colors in association with different dynasties was mentioned in the Lüshi Chunqiu (late 3rd century BCE), where the Yellow Emperor's reign was seen to be governed by earth.[9] The character huang 黃 ("yellow") was often used in place of the homophonous huang 皇, which means "august" (in the sense of 'distinguished') or "radiant", giving Huangdi attributes close to those of Shangdi, the Shang supreme god.[10]

Xuanyuan and Youxiong

The Records of the Grand Historian, compiled by Sima Qian in the first century BCE, gives the Yellow Emperor's name as "Xuan Yuan" (traditional Chinese: 軒轅; simplified Chinese: 轩辕; pinyin: Xuān Yuán). Third-century scholar Huangfu Mi, who wrote a work on the sovereigns of antiquity, commented that Xuanyuan was the name of a hill where Huangdi had lived and that he later took as a name.[11] The Qing dynasty scholar Liang Yusheng (梁玉繩, 1745–1819) argued instead that the hill was named after the Yellow Emperor.[11] Xuanyuan is also the name of the star Regulus in Chinese, the star being associated with Huangdi in traditional astronomy.[12] He is also associated to the broader constellations Leo and Lynx, of which the latter is said to represent the body of the Yellow Dragon (黃龍 Huánglóng), Huangdi's animal form.[13]

Huangdi was also referred to as "Youxiong" (有熊; Yǒuxióng). This name has been interpreted as either a place name or a clan name. According to British sinologist Herbert Allen Giles (1845–1935), that name was "taken from that of [Huangdi's] hereditary principality".[14] William Nienhauser, a modern translator of the Records of the Grand Historian, states that Huangdi was originally the head of the Youxiong clan, which lived near what is now Xinzheng in Henan.[15] Rémi Mathieu, a French historian of Chinese myths and religion, translates "Youxiong" as "possessor of bears" and links Huangdi to the broader theme of the bear in world mythology.[16] Ye Shuxian has also associated the Yellow Emperor with bear legends common across northeast Asia people as well as the Dangun legend.[17]

Other names

Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian describes the Yellow Emperor's ancestral name as Gongsun (公孫).[1]

In Han dynasty texts, the Yellow Emperor is also called upon as the "Yellow God" (黃神 Huángshén).[18] Certain accounts interpret him as the incarnation of the "Yellow God of the Northern Dipper" (黄神北斗 Huángshén Běidǒu),[note 2] another name of the universal god (Shangdi 上帝 or Tiandi 天帝).[19] According to a definition in apocryphal texts related to the Hétú 河圖, the Yellow Emperor "proceeds from the essence of the Yellow God".[20]

As a cosmological deity, the Yellow Emperor is known as the "Great Emperor of the Central Peak" (中岳大帝 Zhōngyuè Dàdì),[3] and in the Shizi as the "Yellow Emperor with Four Faces" (黃帝四面 Huángdì Sìmiàn).[21] In old accounts the Yellow Emperor is identified as a deity of light (and his name is explained in the Shuowen jiezi to derive from guāng 光, "light") and thunder, and as one and the same with the "Thunder God" (雷神 Léishén),[22][23] who in turn, as a later mythological character, is distinguished as the Yellow Emperor's foremost pupil, such as in the Huangdi Neijing.

Historicity

The Chinese historian Sima Qian – and much Chinese historiography following him – considered the Yellow Emperor to be a more historical figure than earlier legendary figures such as Fu Xi, Nüwa, and Shennong. Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian begins with the Yellow Emperor, while passing over the others.[1][24]

Throughout most of Chinese history, the Yellow Emperor and the other ancient sages were considered to be historical figures.[4] Their historicity started to be questioned in the 1920s by historians such as Gu Jiegang, one of the founders of the Doubting Antiquity School in China.[4] In their attempts to prove that the earliest figures of Chinese history were mythological, Gu and his followers argued that these ancient sages were originally gods who were later depicted as humans by the rationalist intellectuals of the Warring States period.[25] Yang Kuan, a member of the same current of historiography, noted that only in the Warring States period had the Yellow Emperor started to be described as the first ruler of China.[26] Yang thus argued that Huangdi was a later transformation of Shangdi, the supreme god of the Shang dynasty's pantheon.[8]

Also in the 1920s, French scholars Henri Maspero and Marcel Granet published critical studies of China's accounts of high antiquity.[27] In his Danses et légendes de la Chine ancienne ["Dances and legends of ancient China"], for example, Granet argued that these tales were "historicized legends" that said more about the time when they were written than about the time they purported to describe.[28]

Most scholars now agree that the Yellow Emperor originated as a god who was later represented as a historical person.[29] K.C. Chang sees Huangdi and other cultural heroes as "ancient religious figures" who were "euhemerized" in the late Warring States and Han periods.[4] Historian of ancient China Mark Edward Lewis speaks of the Yellow Emperor's "earlier nature as a god", whereas Roel Sterckx, a professor at University of Cambridge, calls Huangdi a "legendary cultural hero".[30]

Origin of the myth

The origin of Huangdi's mythology is unclear, but historians have formulated several hypotheses about it. Yang Kuan, a member of the Doubting Antiquity School (1920s–40s), argued that the Yellow Emperor was derived from Shangdi, the highest god of the Shang dynasty.[31][32][33] Yang reconstructs the etymology as follows: Shangdi 上帝 → Huang Shangdi 皇上帝 → Huangdi 皇帝 → Huangdi 黄帝, in which he claims that huang 黃 ("yellow") either was a variant Chinese character for huang 皇 ("august") or was used as a way to avoid the naming taboo for the latter.[34] Yang's view has been criticized by Mitarai Masaru[35] and by Michael Puett.[36]

Historian Mark Edward Lewis agrees that huang 黄 and huang 皇 were often interchangeable, but disagreeing with Yang, he claims that huang meaning "yellow" appeared first.[31] Based on what he admits is a "novel etymology" likening huang 黄 to the phonetically close wang 尪 (the "burned shaman" in Shang rainmaking rituals), Lewis suggests that "Huang" in "Huangdi" might originally have meant "rainmaking shaman" or "rainmaking ritual."[37] Citing late Warring States and early Han versions of Huangdi's myth, he further argues that the figure of the Yellow Emperor originated in ancient rain-making rituals in which Huangdi represented the power of rain and clouds, whereas his mythical rival Chiyou (or the Yan Emperor) stood for fire and drought.[38]

Also disagreeing with Yang Kuan's hypothesis, Sarah Allan finds it unlikely that such a popular myth as the Yellow Emperor's could have come from a taboo character.[32] She argues instead that pre-Shang "'history'," including the story of the Yellow Emperor, "can all be understood as a later transformation and systematization of Shang mythology."[39] In her view, Huangdi was originally an unnamed "lord of the underworld" (or the "Yellow Springs"), the mythological counterpart of the Shang sky deity Shangdi.[32] At the time, Shang rulers claimed that their mythical ancestors, identified with "the [ten] suns, birds, east, life, [and] the Lord on High" (i.e., Shangdi), had defeated an earlier people associated with "the underworld, dragons, west."[40] After the Zhou dynasty overthrew the Shang dynasty in the eleventh century BCE, Zhou leaders reinterpreted Shang myths as meaning that the Shang had vanquished a real political dynasty, which was eventually named the Xia dynasty.[40] By Han times – as seen in Sima Qian's account in the Shiji – the Yellow Emperor, who as lord of the underworld had been symbolically linked to the Xia, had become a historical ruler whose descendants were thought to have founded the Xia.[41]

Given that the earliest extant mention of the Yellow Emperor was on a fourth-century BCE Chinese bronze inscription claiming that he was the ancestor of the royal house of the state of Qi, Lothar von Falkenhausen speculates that Huangdi was invented as an ancestral figure as part of a strategy to claim that all ruling clans in the "Zhou dynasty culture sphere" shared common ancestry.[42]

History of Huangdi's cult

Earliest mention

Explicit accounts of the Yellow Emperor started to appear in Chinese texts the Warring States period. "The most ancient extant reference" to Huangdi is an inscription on a bronze vessel made during the first half of the fourth century BCE by the royal family (surnamed Tian 田) of the state of Qi, a powerful eastern state.[43]

Harvard University historian Michael Puett writes that the Qi bronze inscription was one of several references to the Yellow Emperor in the fourth and third centuries BCE within accounts of the creation of the state.[44] Noting that many of the thinkers who were later identified as precursors of the Huang–Lao – "Huangdi and Laozi" – tradition came from the state of Qi, Robin D. S. Yates hypothesizes that Huang–Lao originated in that region.[45]

Warring States period

The cult of Huangdi became very popular during the Warring States period (5th century–221 BCE), a period of intense competition between rival states which ended with the unification of the realm by the state of Qin.[46] In addition to his role as ancestor, he became associated with "centralized statecraft" and emerged as a figure paradigmatic of emperorship.[47]

The state of Qin

In his Shiji, Sima Qian claims that the state of Qin started worshipping the Yellow Emperor in the fifth century BCE, along with Yandi, the Fiery Emperor.[48] The altars were established at Yong 雍 (near modern Fengxiang County in Shaanxi province), which was the capital of Qin from 677 to 383 BC.[49] By the time of King Zheng, who became king of Qin in 247 and First Emperor of a unified China in 221 BCE, Huangdi had become by far the most important of the four "thearchs" (di 帝) who were then worshiped at Yong.[50]

The Shiji version

The figure of Huangdi had appeared sporadically in Warring States texts. Sima Qian's Shiji (or Records of the Grand Historian, completed around 94 BCE) was the first work to turn these fragments of myths into a systematic and consistent narrative of the Yellow Emperor's "career".[51] The Shiji's account was extremely influential in shaping how the Chinese viewed the origin of their history.[52]

The Shiji begins its chronological account of Chinese history with the life of Huangdi, whom it presents as a sage sovereign from antiquity.[53] It recounts that Huangdi's father was Shaodian[1] and his mother was Fu Pao (附寶).[54] The Yellow Emperor had four wives. His first wife Leizu of Xiling bore him two sons.[1] His other three wives were his second wife Fenglei (封嫘), third wife Tongyu (彤魚) and fourth wife Momu (嫫母).[54][55] The emperor had a total of 25 sons,[56] 14 of whom began their own surnames and clans.[1] The oldest was Shao Hao or Xuan Xiao, who lived in Qingyang by the Yangtze River.[1] Chang Yi, the youngest, lived by the Ruo River. When the Yellow Emperor died, he was succeeded by Chang Yi's son, Zhuan Xu.[1]

The chronological tables found in chapters 13 of the Shiji represent all past rulers – legendary ones such as Yao and Shun, the first ancestors of the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties, as well as the founders of the main ruling houses in the Zhou sphere – as descendants of Huangdi, giving the impression that Chinese history was the history of one large family.[57]

Imperial era

The Yellow Emperor was credited with an enormous number of cultural legacies and esoteric teachings. While Taoism is often regarded in the West as arising from Laozi, Chinese Taoists claim the Yellow Emperor formulated many of their precepts.[58] The Yellow Emperor's Inner Canon (黃帝內經 Huángdì Nèijīng), which presents the doctrinal basis of traditional Chinese medicine, was named after him.[59] He was also credited with composing the Four Books of the Yellow Emperor (黃帝四經 Huángdì Sìjīng), the Yellow Emperor's Book of the Hidden Symbol (黃帝陰符經 Huángdì Yīnfújīng), and the "Yellow Emperor's Four Seasons Poem" included in the Tung Shing fortune-telling almanac.[58]

"Xuanyuan (+ number)" is also the Chinese name for Regulus and other stars of the constellations Leo and Lynx, of which the latter is said to represent the body of the Yellow Dragon.[60] In the Hall of Supreme Harmony in Beijing's Forbidden City, there is also a mirror called the "Xuanyuan Mirror".[61][62]

In Taoism

In the second century CE, Huangdi's role as a deity was diminished because of the rise of a deified Laozi.[63] A state sacrifice offered to "Huang-Lao jun" was not offered to Huangdi and Laozi, as the term Huang-Lao would have meant a few centuries earlier, but to a "yellow Laozi".[64] Nonetheless, Huangdi kept being considered as an immortal: he was seen as a master of longevity techniques and as a god who could reveal new teachings – in the form of texts such as the sixth-century Huangdi Yinfujing – to his earthly followers.[65]

Twentieth century

The Yellow Emperor became a powerful national symbol in the last decade of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) and remained dominant in Chinese nationalist discourse throughout the Republican period (1911–49).[66] The early twentieth century is also when the Yellow Emperor was first referred to as the ancestor of all Chinese people.[67]

Late Qing

Starting in 1903, radical publications started using the projected date of his birth as the first year of the Chinese calendar.[68] Intellectuals such as Liu Shipei (1884–1919) found this practice necessary in order to "preserve the [Han] race" (baozhong 保種) from both dominance by Manchu people and foreign encroachment.[68] Revolutionaries motivated by Anti-Manchuism such as Chen Tianhua (1875–1905), Zou Rong (1885–1905), and Zhang Binglin (1868–1936) tried to foster the racial consciousness they thought was missing from their compatriots, and thus depicted the Manchus as racially inferior barbarians who were unfit to rule over Han Chinese.[69] Chen's widely circulated pamphlets claimed that the "Han race" formed one big family descended from the Yellow Emperor.[70] The first issue (Nov. 1905) of the Minbao 民報 ("People's Journal"[71]), which was founded in Tokyo by revolutionaries of the Tongmenghui, featured the Yellow Emperor on its cover and called Huangdi "the first great nationalist of the world."[72] It was one of several nationalist magazines that featured the Yellow Emperor on their cover in the early twentieth century.[73] The fact that Huangdi meant "yellow" emperor also served to buttress the theory that he was the originator of the "yellow race".[74]

Many historians interpret this sudden popularity of the Yellow Emperor as a reaction to the theories of French scholar Albert Terrien de Lacouperie (1845–94), who in a book called The Western Origin of the Early Chinese Civilization, from 2300 B.C. to 200 A.D. (1892) had claimed that Chinese civilization was founded around 2300 BCE by Babylonian immigrants.[75] Lacouperie's "Sino-Babylonianism" posited that Huangdi was a Mesopotamian tribal leader who had led a massive migration of his people into China around 2300 BCE and founded what later became Chinese civilization.[76] European sinologists quickly rejected these theories, but in 1900 two Japanese historians, Shirakawa Jirō and Kokubu Tanenori, omitted these criticisms and published a long summary that presented Lacouperie's views as the most advanced Western scholarship on China.[77] Chinese scholars were quickly attracted by "the historicization of Chinese mythology" that the two Japanese authors advocated.[78]

Anti-Manchu intellectuals and activists who searched for China's "national essence" (guocui 國粹) adapted Sino-Babylonianism to their needs.[79] Zhang Binglin explained Huangdi's battle with Chi You as a conflict opposing the newly arrived civilized Mesopotamians to backward local tribes, a battle that transformed China into one of the most civilized places in the world.[80] Zhang's reinterpretation of Sima Qian's account "underscored the need to recover the glory of early China."[81] Liu Shipei also presented these early times as the golden age of Chinese civilization.[82] In addition to tying the Chinese to an ancient center of human civilization in Mesopotamia, Lacouperie's theories suggested that China should be ruled by the descendants of Huangdi. In a controversial essay called History of the Yellow Race (Huangshi 黃史), which was published serially from 1905 to 1908, Huang Jie (黃節; 1873–1935) claimed that the "Han race" was the true master of China because it was descended from the Yellow Emperor.[83] Reinforced by the values of filial piety and the Chinese patrilineal clan,[84] the racial vision defended by Huang and others turned vengeance against the Manchus into a duty owed to one's ancestors.[85]

Republican period

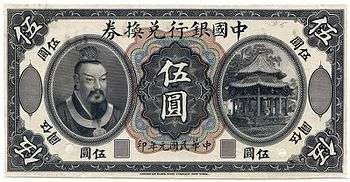

Bottom image: A 100-yuan banknote displaying the Yellow Emperor, issued in 1938 by the Federal Reserve Bank of China of the Provisional Government of the Republic of China (1937–40), a Japanese puppet regime in North China

The Yellow Emperor continued to be revered after the Xinhai Revolution of 1911, which overthrew the Qing dynasty. In 1912, for instance, banknotes carrying Huangdi's effigy were issued by the new Republican government.[86] After 1911, however, the Yellow Emperor as national symbol changed from first progenitor of the Han race to ancestor of China's entire multi-ethnic population.[87] Under the ideology of the Five Races Under One Union, Huangdi became the common ancestor of the Han Chinese, the Manchu people, the Mongols, the Tibetans, and the Hui people, who were said to form the Zhonghua minzu, a broadly understood Chinese nation.[87] Sixteen state ceremonies were held between 1911 and 1949 to Huangdi as the "founding ancestor of the Chinese nation" (中華民族始祖) and even "the founding ancestor of human civilization" (人文始祖).[86]

Modern significance

The cult of the Yellow Emperor was forbidden in the People's Republic of China until the end of the Cultural Revolution.[88] The prohibition was halted during the 1980s when the government reversed itself and resurrected the "Yellow Emperor cult".[89] Starting in the 1980s, the cult was revived and phrases relating to the "Descendants of Yan and Huang" were sometimes used by the Chinese state when referring to people of Chinese descent.[90] In 1984, for example, Deng Xiaoping argued for Chinese reunification saying "Taiwan is rooted in the hearts of the descendants of the Yellow Emperor," whereas in 1986 the PRC acclaimed the Chinese-American astronaut Taylor Wang as the first of the Yellow Emperor's descendants to travel in space.[91] In the first half of the 1980s, the Party had internally debated whether this usage would make ethnic minorities feel excluded. After consulting experts from Beijing University, the Chinese Academy of Social Science, and the Central Nationalities Institute, the Central Propaganda Department recommended on March 27, 1985, that the Party speak of the Zhonghua Minzu – the "Chinese nation" broadly defined – in official statements, but that the phrase "sons and grand-sons of Yandi and the Yellow Emperor" could be used in informal statements by party leaders and in "relations with Hong Kong and Taiwanese compatriots and overseas Chinese compatriots".[92]

After retreating to Taiwan in late 1949 at the end of the Chinese Civil War, Chiang Kai-shek and the Kuomintang (KMT) ruled that the Republic of China (ROC) would keep paying homage to the Yellow Emperor on April 4, the National Tomb Sweeping Day, but neither he nor the three presidents that succeeded him ever paid homage in person.[93] In 1955, the KMT, which was led by Mandarin speakers and still poised on retaking the mainland from the Communists, sponsored the production of the movie Children of the Yellow Emperor (Huangdi zisun 黃帝子孫), which was filmed mostly in Taiwanese Hokkien and showed extensive passages of Taiwanese folk opera. Directed by Bai Ke (1914–1964), a former assistant of Yuan Muzhi, it was a propaganda effort to convince speakers of Taiyu that they were linked to mainland people by common blood.[94] In 2009 Ma Ying-jeou was the first ROC president to celebrate the Tomb Sweeping Day rituals for Huangdi in person, on which occasion he proclaimed that both Chinese culture and common descent from the Yellow Emperor united people from Taiwan and the mainland.[93][95] Later the same year, Lien Chan – a former Vice President of the Republic of China who is now Honorary Chairman of the Kuomintang – and his wife Lien Fang Yu paid homage at the Mausoleum of the Yellow Emperor in Huangling, Yan'an, in mainland China.[93][96]

Gay studies researcher Louis Crompton[97][98][99] has cited Ji Yun's report in his popular Notes from the Yuewei Hermitage (1800), that some claimed the Yellow Emperor was the first Chinese to take male bedmates, a claim that Ji Yun dismissed.[100] Ji Yun argued that this was probably a false attribution.[101]

Elements of Huangdi's myth

As with any myth, there are numerous versions of Huangdi's story, emphasizing different themes and interpreting the main character's significance in different ways.

Birth

According to Huangfu Mi (215–282), the Yellow Emperor was born in Shou Qiu ("Longevity Hill"),[102] which is today on the outskirts of the city of Qufu in Shandong. Early on, he lived with his tribe near the Ji River – Edwin Pulleyblank states that "there seems to be no record of a Ji River outside the myth"[103] – and later migrated to Zhuolu in modern-day Hebei. He then became a farmer and tamed six different special beasts: the bear (熊), the brown bear (罴; 羆), the pí (貔) and xiū (貅) (which later combined to form the mythical Pixiu), the ferocious chū (貙), and the tiger (虎).

Huangdi is sometimes said to have been the fruit of extraordinary birth, as his mother Fubao conceived him as she was aroused, while walking in the country, by a lightning bolt from the Big Dipper. She delivered her son on the mount of Shou (Longevity) or mount Xuanyuan, after which he was named.[104]

Achievements

In traditional Chinese accounts, the Yellow Emperor is credited with improving the livelihood of the nomadic hunters of his tribe. He teaches them how to build shelters, tame wild animals, and grow the Five Grains, although other accounts credit Shennong with the last. He invents carts, boats, and clothing.

Other inventions credited to the emperor include the Chinese diadem (冠冕), throne rooms (宮室), the bow sling, early Chinese astronomy, the Chinese calendar, math calculations, code of sound laws (音律),[106] and cuju, an early Chinese version of football.[107] He is also sometimes said to have been partially responsible for the invention of the guqin zither,[108] although others credit the Yan Emperor with inventing instruments for Ling Lun's compositions.[109]

In traditional accounts, he also goads the historian Cangjie into creating the first Chinese character writing system, the Oracle bone script, and his principal wife Leizu invents sericulture and teaches his people how to weave silk and dye clothes.

At one point in his reign the Yellow Emperor allegedly visited the mythical East sea and met a talking beast called the Bai Ze who taught him the knowledge of all supernatural creatures.[110][111] This beast explained to him there were 11,522 (or 1,522) kinds of supernatural creatures.[110][111]

Battles

The Yellow Emperor and the Yan Emperor were both leaders of a tribe or a combination of two tribes near the Yellow River. The Yan Emperor hailed from a different area around the Jiang River, which a geographical work called the Shuijingzhu identified as a stream near Qishan in what was the Zhou homeland before they defeated the Shang.[103] Both emperors lived in a time of warfare.[112] The Yan Emperor proving unable to control the disorder within his realm, the Yellow Emperor took up arms to establish his domination over various warring factions.[112]

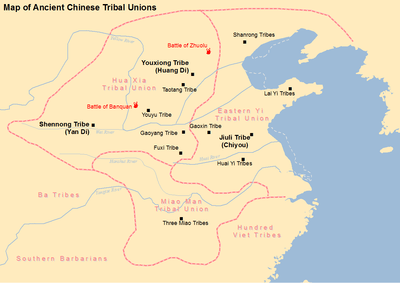

According to traditional accounts, the Yan Emperor meets the force of the "Nine Li" (九黎) under their bronze-headed leader, Chi You, and his 81 horned and four-eyed brothers[5] and suffers a decisive defeat. He flees to Zhuolu and begs the Yellow Emperor for help. During the ensuing Battle of Zhuolu the Yellow Emperor employs his tamed animals and Chi You darkens the sky by breathing out a thick fog. This leads the emperor to develop the south-pointing chariot, which he uses to lead his army out of the miasma.[5] He next calls upon the drought demon Nüba to dispel Chi You's storm.[5] He then destroys the Nine Li and defeats Chi You.[113] Later he engages in battle with the Yan Emperor, defeating him at Banquan and replacing him as the primary ruler.[112]

Death

The Yellow Emperor was said to have lived for over a hundred years before meeting a phoenix and a qilin and then dying.[14] Two tombs were built in Shaanxi within the Mausoleum of the Yellow Emperor, in addition to others in Henan, Hebei and Gansu.[114]

Modern-day Chinese people sometimes refer to themselves as the "Descendants of Yan and Yellow Emperor", although non-Han minority groups in China may have their own myths or not count as descendants of the emperor.[115]

Meaning as a deity

Symbol of the centre of the universe

As the Yellow Deity with Four Faces (黃帝四面 Huángdì Sìmiàn) he represents the centre of the universe and vision of the unity which controls the four directions. It is explained in the Huangdi Sijing ("Four Scriptures of the Yellow Emperor") that regulating "heart within brings order without". In order to reign one must "reduce himself" abandoning emotions, "drying up like a corpse", never allowing oneself to be carried away, as according to the myth the Yellow Emperor himself did during his three years of refuge on Mount Bowang in order to find himself. This practice creates an internal void where all the vital forces of creation gather, and the more indeterminate they remain and the more powerful they will be.[116]

It is from this centre that equilibrium and harmony emanate, equilibrium of the vital organs which becomes harmony between the person and the environment. As sovereign of the centre, the Yellow Emperor is the very image of the concentration or re-centering of the self. By self-control, taking charge of his own body one becomes powerful without. The centre is also the vital point in the microcosm by means of which the internal universe viewed as an altar is created. The body is a universe, and by going into himself and by incorporating the fundamental structures of the universe, the sage will gain access to the gates of Heaven, the unique point where communication between Heaven, Earth and Man can occur. The centre is the convergence of within and without, the contraction of chaos on the point which is equidistant from all directions. It is the place which is no place, where all creation is born and dies.[116]

The Great Deity of the Central Peak (中岳大帝 Zhōngyuèdàdì) is another epithet representing Huangdi as the hub of creation, the axis mundi (which in Chinese mythology is Kunlun) that is the manifestation of the divine order in physical reality, that opens to immortality.[3]

As ancestor

Throughout history, several sovereigns and dynasties claimed (or were claimed) to descend from the Yellow Emperor. Sima Qian's Shiji presented Huangdi as ancestor of the two legendary rulers Yao and Shun, and traced various lines of descent from Huangdi to the founders of the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties. He claimed that Liu Bang, the first emperor of the Han dynasty, was a descendant of Huangdi. He accepted that the ruling house of the Qin dynasty was also issued from the Yellow Emperor, but by stating that Qin Shihuang was in fact the child of Qin chancellor Lü Buwei, he perhaps meant to leave the First Emperor out of Huangdi's descent.

Claiming descent from illustrious ancestors remained a common tool of political legitimacy in the following ages. Wang Mang (c. 45 BCE – 23 CE), of the short-lived Xin dynasty, claimed to descend from the Yellow Emperor in order to justify his overthrow of the Han.[117] As he announced in January of 9 CE: "I possess no virtue, [but] I rely upon the fact that] I am a descendant of my august original ancestor, the Yellow Emperor..."[118] About two hundred years later a ritual specialist named Dong Ba 董巴, who worked for at the court of the Cao Wei, which had recently succeeded the Han, promoted the idea that the Cao family was descended from Huangdi via Emperor Zhuanxu.[119]

During the Tang dynasty, non-Han rulers also claimed descent from the Yellow Emperor, for individual and national prestige, as well as to connect themselves to the Tang.[120] Most Chinese noble families also claimed descent from Huangdi.[121] This practice was well established in Tang and Song times, when hundreds of clans claimed such descent. The main support for this theory – as recorded in the Tongdian (801 AD) and the Tongzhi (mid 12th century) – was the Shiji's statement that Huangdi's 25 sons were given 12 different surnames, and that these surnames had diversified into all Chinese surnames.[122] After Emperor Zhenzong (r. 997–1022) of the Song dynasty dreamed of a figure he was told was the Yellow Emperor, the Song imperial family started to claim Huangdi as its first ancestor.[123]

A number of overseas Chinese clans that keep a genealogy also trace their family ultimately to Huangdi, explaining their different surnames as name changes claimed to have derived from the fourteen surnames of Huangdi's descendants.[124] Many Chinese clans, both overseas and in China, claim Huangdi as their ancestor to reinforce their sense of being Chinese.[125]

Gun, Yu, Zhuanxu, Zhong, Li, Shujun, and Yuqiang are various emperors, gods, and heroes whose ancestor was also supposed to be Huangdi. The Huantou, Miaomin, and Quanrong peoples were said to be descended from Huangdi.[126]

Traditional dates

.jpg)

Although the traditional Chinese calendar did not mark years continuously, some Han-dynasty astronomers tried to determine the years of the life and reign of the Yellow Emperor. In 78 BCE, under the reign of Emperor Zhao of Han, an official called Zhang Shouwang (張壽望) calculated that 6,000 years had passed since the time of Huangdi; the court refused his proposal for reform, countering that only 3,629 years had elapsed.[127] In the proleptic Julian calendar, the court's calculations would have placed the Yellow Emperor in the late 38th century BCE rather than in the 27th century BCE that is conventional nowadays.

During their Jesuit missions in China in the seventeenth century, the Jesuits tried to determine what year should be considered the epoch of the Chinese calendar. In his Sinicae historiae decas prima (first published in Munich in 1658), Martino Martini (1614–1661) dated the royal ascension of Huangdi to 2697 BCE, but started the Chinese calendar with the reign of Fuxi, which he claimed started in 2952 BCE.[128] Philippe Couplet's (1623–1693) "Chronological table of Chinese monarchs" (Tabula chronologica monarchiae sinicae; 1686) also gave the same date for the Yellow Emperor.[129] The Jesuits' dates provoked great interest in Europe, where they were used for comparisons with Biblical chronology.[130] Modern Chinese chronology has generally accepted Martini's dates, except that it usually places the reign of Huangdi in 2698 BCE (see next paragraph) and omits Huangdi's predecessors Fuxi and Shennong, who are considered "too legendary to include."[131]

Helmer Aslaksen, a mathematician who teaches at the National University of Singapore and specializes in the Chinese calendar, explains that those who use 2698 BCE as a first year probably do so because they want to have "a year 0 as the starting point", or because "they assume that the Yellow Emperor started his year with the Winter solstice of 2698 BCE", hence the difference with the year 2697 BCE calculated by the Jesuits.[132]

Starting in 1903, radical publications started using the projected date of birth of the Yellow Emperor as the first year of the Chinese calendar.[68] Different newspapers and magazines proposed different dates. Jiangsu, for example counted 1905 as year 4396 (making 2491 BCE the first year of the Chinese calendar), whereas the Minbao (the organ of the Tongmenghui) reckoned 1905 as 4603 (first year: 2698 BCE).[133] Liu Shipei (1884–1919) created the Yellow Emperor Calendar to show the unbroken continuity of the Han race and Han culture from earliest times. There is no evidence that this calendar was used before the 20th century.[134] Liu's calendar started with the birth of the Yellow Emperor, which was reckoned to be 2711 BCE.[135] When Sun Yat-sen declared the foundation of the Republic of China on January 2, 1912, he decreed that this was the 12th day of the 11th month of year 4609 (epoch: 2698 BCE), but that the state would now be using the solar calendar and count 1912 as the first year of the Republic.[136] Chronological tables published in the 1938 edition of the Cihai (辭海) dictionary followed Sun Yat-sen in using 2698 as the year of Huangdi's accession; this chronology is now "widely reproduced, with little variation."[137]

Cultural references

- The emperor appears as an ancestor hero in the strategy game Emperor: Rise of the Middle Kingdom made by Sierra Entertainment. In the game, he is a patron of acupuncturist and silk weaver, and has the skills needed for leading men into battle, especially the Chariot-Fort soldiers.

- The emperor serves as the hero in Jorge Luis Borges's story, "The Fauna of the Mirror". British fantasy writer China Miéville used this story as the basis for his novella The Tain, which describes a post-apocalyptic London. "The Tain" was included in Miéville's short-story collection "Looking For Jake" (2005).

- The popular Chinese role-playing video game series for the PC, Xuanyuan Jian, revolves around the legendary sword used by the emperor.

- The emperor is an important NPC in the action RPG Titan Quest, The player must reach the emperor to learn the truth about Typhon's imprisonment. He also reveals a bit of information about the war between the gods and the titans, while also revealing that he has been following the players actions since the beginning of the Silk Road.

- A 2016 Chinese drama film about the story of the Yellow Emperor is titled "Xuan Yuan: The Great Emperor" (軒轅大帝).[138]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yellow Emperor. |

- Chinese folk religion

- Chinese theology

- Emperors Yan and Huang (monument)

- Jiutian Xuannü, goddess of war, sex, and longevity as well as teacher of the Yellow Emperor

- Simianshen

- Tianxia

- Xuanyuanism

Notes

- In Chinese thought mythological history and cosmology are two points of view to describe the same reality. In other words, mythology and history and theology and cosmology are all interrelated.

- A 斗 dǒu in Chinese is an entire semantic field meaning the shape of a "dipper", as the Big Dipper (北斗 Běidǒu), or a "cup", signifying a "whirl", and also has martial connotations meaning "fight", "struggle", "battle".

References

- Sima Qian, Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji 史記, c. 100 BCE), Chapter 1, "Wudi benji" 五帝本紀 ("Annals of the Five Emperors"); on Chinese Text Project (retrieved on 2016-10-08).

- "Huang Ti". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- Fowler (2005), pp. 200-201.

- Chang 1983, p. 2

- Wang 2005, pp. 11–13.

- Allan 1984, p. 245: "Only after the 'First Emperor' of Qin styled himself Shi Huangdi, did huangdi come to refer to an earthly ruler rather than the August Lord"

- Major 1993, p. 18: "Thearch captures well the character of ancient Chinese thought wherein divinities might be (simultaneously and without internal contradiction) high gods, mythical/divine rulers, or deified royal ancestors: beings of enormous import, straddling the numinous and the mundane."

- Allan 1991, p. 65.

- Walters 2006, p. 39.

- Engelhardt (2008), pp. 504-505.

- Nienhauser 1994, p. 1, note 6.

- Ho, Peng Yoke. Li, Qi and Shu: An Introduction to Science and Civilization in China. Courier Corporation, 2000. ISBN 0486414450. p. 135

- Sun & Kistemaker (1997), pp. 120–123.

- Giles 1898, p. 338, cited in Unschuld & Tessenow 2011, p. 5.

- Nienhauser 1994, p. 1, note 3.

- Mathieu 1984, p. 29, p. 243.

- Ye 2007.

- Poo 2011, p. 20.

- Espesset 2007, p. 1080.

- Espesset (2007), pp. 22-28.

- Sun & Kistemaker (1997), p. 120.

- SCPG Publishing Corp. The Deified Human Face Petroglyphs of Prehistoric China. World Scientific, 2015. ISBN 1938368339. p. 239: in the Hetudijitong and the Chunqiuhechengtu the Yellow Emperor is identified as the Thunder God.

- Yang, Lihui; An, Deming. Handbook of Chinese Mythology. ABC-CLIO, 2005. ISBN 157607806X. p. 138

- Wu 1982, pp. 49–50, and chapter endnotes.

- Puett 2001, p. 93 (description of Gu's general purpose); Lewis 2007, p. 545 (rest of the information).

- Allan 1991, p. 64.

- Lewis 2007, p. 545.

- Lewis 2007, pp. 545–46.

- Lewis 2007, p. 556: "modern scholars of myth generally agree that the sage kings were partially humanized transformations of earlier, supernatural beings who figured in shamanistic rituals, cosmogonic myths or tales of the origins of tribes and clans."

- Lewis 2007, p. 565; Sterckx 2002, p. 95.

- Lewis 1990, p. 314, note 116.

- Allan 1991, p. 65.

- Puett 2001, p. 97.

- Lewis 1990, p. 314, note 116 (huang 黄 as variant); Allan 1991, p. 65 (huang 黄 as taboo character).

- Mitarai 1967.

- Puett 2001, pp. 246–47, note 16..

- Lewis 1990, p. 194.

- Lewis 1990, pp. 179–82.

- Allan 1991, p. 175.

- Allan 1991, p. 73.

- Allan 1991, pp. 64, 73, 175: "In the Xia annals of the Shiji, the Xia ancestry is traced from Yu 禹 back to Huang Di, the Yellow Lord"; "the lord of the underworld and Yellow Springs and thus closely associated with the Xia"; "By the Han, their [the Xia] ancestor, the Yellow Emperor, originally the lord of the underworld, had been transformed into an historical figure who, with his descendant Zhuan Xu, ruled before Yao".

- von Falkenhausen 2006, p. 165 ("Warring States texts document a variety of attempts to coordinate all or most of the clans of the Zhou culture sphere under a common genealogy descended from the mythical Yellow Emperor (Huangdi), who may have been invented for that very purpose").

- LeBlanc 1985–1986, p. 53 (quotation); Seidel 1969, p. 21 (who calls it "the most ancient document on Huangdi" ["le plus ancient document sur Houang Ti"]); Jan 1981, p. 118 (who calls the inscription "the earliest existing and datable source of the Yellow Emperor cult" and claims that the vessel dates either from 375 or 356 BCE; Chang 2007, p. 122 (who gives the date as 356 BCE); Puett 2001, p. 112 (Huangdi's "first appearance in early Chinese literature is a passing reference in a bronze inscription, where he is mentioned as an ancestor of the patron of the vessel"); Yates 1997, p. 18 ("earliest extant reference" to Huangdi is "in a bronze inscription dedicated by King Wei" (r. 357–320); von Glahn 2004, p. 38 (which calls Qi "the dominant state in eastern China" at the time).

- Puett 2001, p. 112.

- Yates 1997, p. 19.

- Sun 2000, p. 69.

- Puett 2002, p. 303 ("centralized statecraft"; LeBlanc 1985–1986, pp. 50–51 ("paradigmatic emperorship").

- von Glahn 2004, p. 38; Lewis 2007, p. 565. Both scholars rely on a claim made in chapter 28 of the Shiji, p. 1364 of the Zhonghua Shuju edition.

- von Glahn 2004, p. 43.

- von Glahn 2004, p. 38 ("By the reign of King Zheng, the future First Emperor of Qin, the cult of Huangdi overshadowed all of its rivals for the attention of the Qin rulers").

- Yi 2010, in section titled "Yan–Huang chuanshuo 炎黄传说" ("The legends of Yandi and Huangdi") (original: "到了司马迁《史记》才有较系统记述.... 《史记·五帝本纪》整合成了一个相对完整的故事"); Lewis 1990, p. 174 ("the earliest surviving sequential narrative of the career of the Yellow Emperor"); Birrell 1994, p. 86 ("[Sima Qian] composed a seamless biographical account of the deity that had no basis in the earlier classical texts that recorded myth narratives.").

- Loewe 1998, p. 977.

- Nienhauser 1994, p. 18 (in "Translators' note").

- Chinareviewnews.com, "The ugliest among the empresses and consorts of past ages" 歷代后妃中的超級醜女 (in Chinese). Retrieved on August 8, 2010.

- Big5.huaxia.com, "Momu and the Yellow Emperor invent the mirror" 嫫母與軒轅作鏡 (in Chinese). Retrieved on 2010-09-04.

- Sautman 1997, p. 81.

- Vankeerberghen 2007, pp. 300–301.

- Windridge & Fong 2003, pp. 59 and 107.

- Unschuld & Tessenow 2011, p. 5.

- Sun & Kistemaker (1997), pp. 120-123.

- Maine.edu, "Hall of Supreme Harmony." Retrieved on 2010-08-29.

- Singtao.ca, "The Xuanyuan mirror in the Imperial Throne Room – the Hall of Supreme Harmony where the emperor held court" 金鑾寶座軒轅鏡 御門聽政太和殿 (in Chinese). Retrieved on 2010-08-29.

- Engelhardt 2008, p. 506.

- Lagerwey 1987, p. 254.

- Komjathy 2013, pp. 173 (date of the Yinfujing and 186, note 77 (rest of the information).

- Duara 1995, p. 76.

- Sun 2000, p. 69: "中华这个五千年文明古国由黄帝开国、中国人都是黄帝子孙的说法, 则是20 世纪的产品": "The claims that the 5000-year-old Chinese civilization was inaugurated by Huangdi and that Chinese people are the descendants of Huangdi are products of the twentieth century."

- Dikötter 1992, p. 116.

- Dikötter 1992, pp. 117–18.

- Dikötter 1992, p. 117.

- Chow 1997, p. 49.

- Sun 2000, pp. 77–78; Dikötter 1992, p. 116, note 73.

- Dikötter 1992, p. 116, note 73.

- Chow 2001, p. 59.

- Hon 2010, p. 140.

- Hon 2010, p. 145.

- Hon 2010, pp. 145–47.

- Hon 2010, p. 149.

- Hon 2010, p. 150.

- Hon 2010, pp. 151–52.

- Hon 2010, p. 153.

- Hon 2010, p. 154.

- Hon 2003, pp. 253–54.

- Duara 1995, p. 75.

- Dikötter 1992, pp. 71 and 117 ("racial loyalty was perceived as an extension of lineage loyalty"; Hon 2010, p. 150 ("call to arms.... to wage a racial war against the Manchus").

- Liu 1999, pp. 608–9.

- Liu 1999, p. 609.

- Sautman 1997, pp. 79–80.

- Sautman 1997, p. 80.

- Sautman 1997, pp. 80–81.

- Sautman 1997, p. 81.

- Schoenhals 2008, pp. 121–22.

- "President Ma pays homage in person to the Yellow Emperor", China post, Formosa, September 4, 2010.

- Zhang 2013, p. 6.

- Tan 2009, p. 40.

- "10,000 Chinese pay homage to Yellow Emperor", China daily, September 4, 2010.

- Louis Crompton (1925–2009), UNL.

- "Louis Crompton Scholarship", LGBTQA Programs & Services.

- Louis Crompton Scholarship Fund, NU foundation, archived from the original on May 18, 2012, retrieved April 4, 2012.

- Crompton 2003, p. 214.

- Yun, Ji, "Huaixi zazhi er" 槐西雜志二 [Miscellaneous records from Huaixi, Part 2], Yuewei caotang biji 閱微草堂筆記,

雜說稱孌童始黃帝, 殆出依托

. - Nienhauser 1994, p. 1, note 6.

- Pulleyblank 2000, p. 14, note 39.

- Yves Bonnefoy, Asian Mythologies. University of Chicago Press, 1993. ISBN 0226064565. p. 246

- Birrell 1993, p. 48.

- Wang 1997, p. 13.

- Liu Xiang (77–6 BCE), Bielu 别录:"It is said that cuju was invented by Huangdi; others claim that it arose during the Warring States period" (蹴鞠者,传言黄帝所作,或曰起戰國之時); cited in Book of the Later Han (5th century), chapter 34, p. 1178 of the standard Zhonghua shuju edition. (in Chinese)

- Yin 2001, pp. 1–10.

- Huang 1989, vol. 2 .

- iFeng.com, "The traitor Bai Ze" 背叛者白澤 Archived July 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine (in Chinese); from Xu 2008. Retrieved on 2010-09-04.

- Ge 2005, p. 474.

- Haw 2007, pp. 15–16.

- Roetz 1993, p. 37.

- China.org.cn, "Mausoleums of the Yellow Emperor." Retrieved on 2010-08-29.

- Sautman 1997, p. 83.

- Lévi (2007), p. 674.

- Loewe 2000, p. 542.

- Wang 2000, pp. 168-169.

- Goodman 1998, p. 145.

- Lewis 2009, p. 202; Abramson 2008, p. 154.

- Engelhardt 2008, p. 505.

- Ebrey 2003, p. 171.

- Lagerwey 1987, p. 258.

- Pan 1994, pp. 10–12.

- Sautman 1997, p. 79.

- Yang & An 2005, p. 143.

- Loewe 2000, p. 691, referring to Book of Later Han, chapter 21A, p. 978 of the standard Zhonghua shuju edition.

- Mungello 1989, p. 132.

- Lach & van Kley 1994, p. 1683.

- Mungello 1989, p. 133.

- Mungello 1989, pp. 131–32 (the citation is on p. 132).

- Helmer Aslaksen, "The Mathematics of the Chinese Calendar," Archived April 24, 2006, at the Wayback Machine section "Which Year is it in the Chinese Calendar?" (retrieved on 2011-11-18)

- Wilkinson 2013, p. 519.

- Cohen (2012), pp. 1, 4.

- Kaske 2008, p. 345.

- Wilkinson 2013, p. 507.

- Mungello 1989, p. 131, note 78.

- 軒轅大帝 (2016)

Works cited

- Abramson, Mark Samuel (2008), Ethnic Identity in Tang China, University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 978-0-8122-4052-8

- Allan, Sarah (1984), "The Myth of the Xia Dynasty", The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, 116 (2): 242–256, doi:10.1017/S0035869X00163580, JSTOR 25211710 – via JSTOR (subscription required)

- ——— (1991), The Shape of the Turtle, Albany, NY: SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-0460-9.

- Birrell, Anne (1993), Chinese Mythology: An Introduction, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-4595-5, 0-8018-6183-7.

- ——— (1994), "Studies on Chinese Myth Since 1970: An Appraisal, Part 2", History of Religions, 34 (1): 70–94, doi:10.1086/463382, JSTOR 1062979 – via JSTOR (subscription required)

- Chang, Chun-shu (2007), The Rise of the Chinese Empire, 1. Nation, State, and Imperialism in Early China, ca. 1600 BC – AD 157, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, ISBN 978-0-472-11533-4.

- Chang, K.C. (1983), Art, Myth, and Ritual: The Path to Political Authority in Ancient China, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-04807-5, 0-674-04808-3.

- Chow, Kai-wing (1997), "Imagining Boundaries of Blood: Zhang Binglin and the Invention of the Han 'Race' in Modern China", in Dikötter, Frank (ed.), The Construction of Racial Identities in China and Japan: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, pp. 34–52, ISBN 962-209-443-0.

- ——— (2001), "Narrating Nation, Race, and National Culture: Imagining the Hanzu Identity in Modern China", in Chow, Kai-wing; Doak, Kevin Michael; Fu, Poshek (eds.), Constructing Nationhood in Modern East Asia, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp. 47–84, ISBN 0-472-09735-0, 0-472-06735-4.

- Cohen, Alvin (2012), "Brief Note: The Origin of the Yellow Emperor Era Chronology" (PDF), Asia Major, 25 (pt 2): 1–13CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Crompton, Louis (2003), Homosexuality and Civilization, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-02233-1.

- Dikötter, Frank (1992), The Discourse of Race in Modern China, London: Hurst & Co, ISBN 1-85065-135-3

- Duara, Prasenjit (1995), Rescuing History from the Nation: Questioning Narratives of Modern China, Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-16722-0

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (2003), Women and the family in Chinese history, London and New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-28822-3 (hardback); ISBN 0-415-28823-1 (paperback). – via Questia (subscription required)

- Engelhardt, Ute (2008), "Huangdi 黃帝", in Pregadio, Fabrizio (ed.), The Encyclopedia of Taoism, Routledge, pp. 504–6, ISBN 978-1135796341CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Espesset, Grégoire (2007), "Latter Han religious mass movements and the early Daoist church", in Lagerwey, John; Kalinowski, Marc (eds.), Early Chinese Religion: Part One: Shang Through Han (1250 BC–220 AD), Leiden: Brill, pp. 1061–1102, ISBN 978-90-04-16835-0CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fowler, Jeanine D. (2005), An Introduction to the Philosophy and Religion of Taoism: Pathways to Immortality, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 1845190866CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ge, Hong [283–343] (2005), Gu Jiu 顧久 (ed.), Baopuzi neipian 抱朴子內篇, Taipei: Taiwan shufang chuban youxian gongsi 台灣書房出版有限公司, ISBN 978-986-7332-46-2.

- Giles, Herbert Allen (1898), A Chinese Biographical Dictionary, London: B. Quaritch

- Goodman, Howard L. (1998), Ts'ao P'i Transcendent: The Political Culture of Dynasty-Founding in China at the End of the Han, Seattle, Wash.: Scripta Serica, distributed by Curzon Press, ISBN 0-9666300-0-9

- Haw, Stephen G. (2007), Beijing: A Concise History, London and New York: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-39906-7.

- Hon, Tze-ki (2003), "National Essence, National Learning, and Culture: Historical Writings in Guocui xuebao, Xueheng, and Guoxue jikan", Historiography East & West, 1 (2): 242–86, doi:10.1163/157018603774004511.

- Hon, Tze-ki (2010), "From a Hierarchy in Time to a Hierarchy in Space: The Meanings of Sino-Babylonianism in Early Twentieth-Century China", Modern China, 36 (2): 136–69, doi:10.1177/0097700409345126.

- Huang, Dashou 黃大受 (1989), Zhongguo tongshi 中國通史 [General history of China] (in Chinese), Wunan tushu chuban gufen youxian gongsi 五南圖書出版股份有限公司, ISBN 978-957-11-0031-9

- Jan, Yün-hua (1981), "The Change of Images: The Yellow Emperor in Ancient Chinese Literature", Journal of Oriental Studies, 19 (2): 117–37.

- Kaske, Elizabeth (2008), The Politics of Language in Chinese Education, 1895–1919, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-16367-6.

- Komjathy, Louis (2013), The Way of Complete Perfection: A Quanzhen Daoist Anthology, Albany, NY: SUNY Press, ISBN 978-1-4384-4651-6

- Lach, Donald F.; van Kley, Edwin J. (1994), Asia in the Making of Europe, III. A Century of Advance, Book Four, East Asia, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-46734-4.

- Lagerwey, John (1987), Taoist Ritual in Chinese Society and History, New York and London: MacMillan, ISBN 0-02-896480-2

- LeBlanc, Charles (1985–1986), "A Re-examination of the Myth of Huang-ti", Journal of Chinese Religions, 13–14: 45–63, doi:10.1179/073776985805308158.

- Lévi, Jean (2007), "The rite, the norm and the Dao: Philosophy of sacrifice and transcendence of power in ancient China", in Lagerwey, John; Kalinowski, Marc (eds.), Early Chinese Religion: Part One: Shang Through Han (1250 BC–220 AD), Leiden: Brill, pp. 645–692, ISBN 978-90-04-16835-0CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lewis, Mark Edward (1990), Sanctioned Violence in Early China, Albany, NY: SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-0076-X; 0-7914-0077-8.

- ——— (2007), "The mythology of early China", in John Lagerwey; Marc Malinowski (eds.), Early Chinese Religion: Part One: Shang through Han (1250 BC – 220 AD, Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 543–594, ISBN 978-90-04-16835-0.

- ——— (2009), China's Cosmopolitan Empire: the Tang Dynasty, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-03306-1

- Liu, Li (1999), "Who were the ancestors? The origins of Chinese ancestral culture and racial myths", Antiquity, 73 (281): 602–13, doi:10.1017/S0003598X00065170.

- Loewe, Michael (1998), "The Heritage Left to the Empires", in Michael Loewe; Edward L. Shaughnessy (eds.), The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 B.C., Cambridge (UK) and New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 967–1032, ISBN 0-521-47030-7

- ——— (2000), A Biographical Dictionary of the Qin, Former Han and Xin Periods (221 BC – AD 24), Leiden and Boston: Brill, ISBN 9004103643

- Major, John S. (1993), Heaven and Earth in Early Han Thought: Chapters Three, Four, and Five of the Huainanzi, Albany, NY: SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-1585-6 (hardback), ISBN 0-7914-1586-4 (paperback).

- Mathieu, Rémi (1984), "La Patte de l'ours" [The bear's paw], L'Homme, 24 (1): 5–42, doi:10.3406/hom.1984.368468, JSTOR 25132024 – via JSTOR (subscription required)

- Mitarai, Masaru 御手洗 勝 (1967), "Kōtei densetsu ni tsuite" 黃帝伝説について [About the legend of the Yellow Emperor], Hiroshima Daigaku Bungaku Kiyō 広島大学文学部紀要 ["Bulletin of the Literature Department of Hiroshima University"], 27: 33–59 Italic or bold markup not allowed in:

|journal=(help). - Mungello, David E. (1989) [1985], Curious Land: Jesuit Accommodation and the Origins of Sinology, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, ISBN 0-8248-1219-0.

- Nienhauser, William H Jr, ed. (1994), The Grand Scribe's Records, 1. The Basic Annals of Pre-Han China, Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University press, ISBN 0-253-34021-7.

- Pan, Lynn (1994), Sons of the Yellow Emperor: A History of the Chinese Diaspora, New York: Kodansha America, ISBN 1-56836-032-0.

- Poo, Mu-chou (2011), "Preparation for the Afterlife in Ancient China", in Amy Olberding; Philip J. Ivanhoe (eds.), Mortality in Traditional Chinese Thought, Albany, NY: SUNY Press, pp. 13–36, ISBN 978-1438435640 – via Project MUSE (subscription required)

- Puett, Michael (2001), The Ambivalence of Creation: Debates Concerning Innovation and Artifice in Early China, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-3623-5.

- Puett, Michael (2002), To Become a God: Cosmology, Sacrifice, and Self-Divinization in Early China, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, ISBN 0-674-01643-2.

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (2000), "Ji 姬 and Jiang 姜: The Role of Exogamic Clans in the Organization of the Zhou Polity" (PDF), Early China, 25: 1–27, doi:10.1017/S0362502800004259, JSTOR 23354272.

- Roetz, Heiner (1993), Confucian ethics of the axial age: a reconstruction under the aspect of the breakthrough toward postconventional thinking, SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-1649-6

- Sautman, Barry (1997), "Myths of Descent, Racial Nationalism and Ethnic Minorities in the People's Republic of China", in Dikötter, Frank (ed.), The Construction of Racial Identities in China and Japan: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, pp. 75–95, ISBN 962-209-443-0.

- Schoenhals, Michael (2008), (subscription required), "Abandoned or Merely Lost in Translation?", Inner Asia, 10 (1): 113–30, doi:10.1163/000000008793066777, JSTOR 23615059.

- Seidel, Anna K (1969), La divinisation de Lao Tseu dans le taoisme des Han [The divinization of Laozi in Han-dynasty Taoism] (in French), Paris: École française d'Extrême-Orient, ISBN 2-85539-553-4.

- Sterckx, Roel (2002), The Animal and the Daemon in Early China, Albany, NY: SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-5269-7, 0-7914-5270-0.

- Sun, Longji 孙隆基 (2000), "Qingji minzu zhuyi yu Huangdi chongbai zhi faming" 清季民族主义与黄帝崇拜之发明 [Qing-period nationalism and the invention of the worship of Huangdi], Lishi Yanjiu 历史研究, 2000 (3): 68–79, archived from the original on March 31, 2012, retrieved November 7, 2011CS1 maint: ref=harv (link).

- Sun, Xiaochun; Kistemaker, Jacob (1997), The Chinese Sky During the Han: Constellating Stars and Society, Brill, Bibcode:1997csdh.book.....S, ISBN 9004107371CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tan, Zhong 譚中 (May 1, 2009), "Cong Ma Yingjiu 'yaoji Huangdi ling' kan Zhongguo shengcun shizhi" 從馬英九「遙祭黃帝陵」看中國生存實質, Haixia Pinglun 海峽評論, 221: 40–44.

- Unschuld, Paul U.; Tessenow, Hermann, eds. (2011), Huang Di Nei Jing Su Wen: An Annotated Translation of Huang Di's Inner Classic – Basic Questions, 2 volumes, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 9780520266988

- Vankeerberghen, Griet (2007), "The Tables (biao) in Sima Qian's Shi ji: Rhetoric and Remembrance", in Francesca Bray; Vera Dorofeeva-Lichtmann; Georges Métailié (eds.), Graphics and Text in the Production of Technical Knowledge in China: The Warp and the Weft, Leiden and Boston: E.J. Brill, pp. 295–311, ISBN 978-90-04-16063-7.

- von Falkenhausen, Lothar (2006), Chinese Society in the Age of Confucius (1000–250 BC): The Archaeological Evidence, Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, University of California, ISBN 1-931745-31-5.

- von Glahn, Richard (2004), The Sinister Way: The Divine and the Demonic in Chinese Religious Culture, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-23408-1.

- Walters, Derek (2006), The Complete Guide to Chinese Astrology: The Most Comprehensive Study of the Subject Ever Published in the English Language, Watkins, ISBN 978-1-84293-111-0.

- Wang, Aihe (2000), Cosmology and Political Culture in Early China, Cambridge, Eng.: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-62420-7

- Wang, Hengwei 王恒伟 (2005), Zhongguo lishi jiangtang 中国历史讲堂 [Lectures on Chinese history] (in Chinese), Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 中华书局, ISBN 962-8885-24-3

- Wang, Zhongfu 王仲孚 (1997), Zhongguo wenhua shi 中國文化史 [Chinese cultural history] (in Chinese), Wunan tushu chuban gufen youxian gongsi 五南圖書出版股份有限公司, ISBN 978-957-11-1427-9

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2013), Chinese History: A New Manual, Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Asia Center, ISBN 978-0-674-06715-8.

- Windridge, Charles; Fong, Cheng Kam (2003) [1999], Tong Sing: The Chinese Book of Wisdom Based on the Ancient Chinese Almanac, Kyle Cathie, ISBN 0-7607-4535-8.

- Wu, Kuo-cheng (1982), The Chinese Heritage, New York: Crown, ISBN 0-517-54475-X.

- Xu, Lai 徐来 (2008), Xiangxiang zhong de dongwu: shanggu shidai de qiyi niaoshou 想象中的动物:上古时代的奇异鸟兽 [Imaginary animals: the strange bird-beasts of high antiquity] (in Chinese), Shanghai: Shanghai wenyi chubanshe 上海文艺出版社, ISBN 978-7-80685-826-4

- Yang, Lihui; An, Deming, with Jessica Anderson Turner (2005), Handbook of Chinese Mythology, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-533263-6

- Yates, Robin D.S. (1997), Five Lost Classics: Tao, Huang-Lao, and Yin-Yang in Han China, New York: Ballantine, ISBN 978-0-345-36538-5.

- Ye, Shuxian 叶舒宪 (2007), Xiong tuteng: Zhonghua zuxian shenhua tanyuan 熊图腾:中华祖先神话探源 [The bear totem: the origins of the Chinese ancestral myth] (in Chinese), Shanghai: Shanghai wenyi chubanshe 上海文艺出版社, ISBN 978-7-80685-826-4

- Yi, Hua 易华 (2010), "Yao-Shun yu Yan-Huang: Shiji "Wudi benji" yu minzu rentong" 尧舜与炎黄──《史记•五帝本记》与民族认同 [Yao-Shun and Yan-Huang: the Shiji's "Basic Annals of the Five Emperors" and ethnic identity], China Folklore NetworkCS1 maint: ref=harv (link).

- Yin, Wei 殷伟 (2001), Zhongguo qinshi yanyi 中国琴史演义 [The romance of the history of the Chinese zither] (in Chinese), Yunnan renmin chubanshe 云南人民出版社 [Yunnan People's Press]

- Zhang, Yingjin (2013), "Articulating Sadness, Gendering Space: The Politics and Poetics of Taiyu Films from 1960s Taiwan", Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, 25 (1): 1–46, JSTOR 42940461 – via JSTOR (subscription required)

Further reading

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mark (2006), "Reimagining the Yellow Emperor's Four Faces", in Martin Kern (ed.), Text and Ritual in Early China, Seattle: University of Washington Press, pp. 226–248 – via Project MUSE (subscription required)

- Harper, Donald (1998), Early Chinese Medical Literature: The Mawangdui Medical Manuscripts, London and New York: Kegan Paul International, ISBN 0-7103-0582-6.

- Jochim, Christian (1990), "Flowers, Fruit, and Incense Only: Elite versus Popular in Taiwan's Religion of the Yellow Emperor", Modern China, 16 (1): 3–38, doi:10.1177/009770049001600101.

- Leibold, James (2006), "Competing Narratives of Racial Unity in Republican China: From the Yellow Emperor to Peking Man", Modern China, 32 (2): 181–220, doi:10.1177/0097700405285275.

- Luo, Zhitian 罗志田 (2002), "Baorong Ruxue, zhuzi yu Huangdi de Guoxue: Qingji shiren xunqiu minzu rentong xiangzheng de nuli" 包容儒學、諸子與黃帝的國學:清季士人尋求民族認同象徵的努力 [The Rise of "National Learning": Confucianism, the Ancient Philosophers, and the Yellow Emperor in Chinese Intellectuals' Search for a Symbol of National Identity in the Late Qing], Taida Lishi Xuebao 臺大歷史學報, 29: 87–105.

- Sautman, Barry (1997), "Racial nationalism and China's external behavior", World Affairs, 160: 78–95.

- Schneider, Lawrence (1971), Ku Chieh-gang and China's New History: Nationalism and the Quest for Alternative Traditions, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 9780520018044.

- Seidel, Anna K. (1987), "Traces of Han Religion in Funeral Texts Found in Tombs", in Akizuki, Kan'ei 秋月观暎 (ed.), Dōkyo to shukyō bunka 道教と宗教文化 [Taoism and religious culture], Tokyo: Hirakawa shuppansha 平和出版社, pp. 23–57.

- Shen, Sung-chiao 沈松橋 (1997), "Wo yi wo xue jian Xuan Yuan: Huangdi shenhua yu wan-Qing de guozu jiangou" 我以我血薦軒轅: 黃帝神話與晚清的國族建構 [The myth of the Yellow Emperor and the construction of Chinese nationhood in the late Qing period], Taiwan Shehui Yanjiu Jikan 台灣社會研究季刊, 28: 1–77.

- Unschuld, Paul U (1985), Medicine in China: A History of Ideas, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-05023-1.

- Wang, Ming-ke 王明珂 (2002), "Lun Panfu: Jindai Yan-Huang zisun guozu jiangou de gudai jichu" 論攀附:近代炎黃子孫國族建構的古代基礎 [On progression: the ancient basis for the nation-building claim that the Chinese are descendants of Yandi and Huangdi], Zhongyang Yanjiu Yuan Lishi Yuyan Yanjiusuo Jikan 中央研究院歷史語言研究所集刊, 73 (3): 583–624.

Yellow Emperor | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Yandi |

Mythological Emperor of China c. 2698 BC – c. 2598 BC |

Succeeded by Shaohao |