House of Zhao

The House of Zhao (traditional Chinese: 趙; simplified Chinese: 赵; pinyin: Zhào; Wade–Giles: Chao) was the imperial clan of the Song Empire (960–1279) of China.

| Zhao | |

|---|---|

| Country | Song Empire (China) |

| Founded | 960 |

| Founder | Zhao Kuangyin |

| Final ruler | Zhao Bing |

| Titles | Emperor of the Song Empire |

| Estate(s) | Palaces in Kaifeng and Hangzhou |

| Deposition | 1279 |

Family history

Origin

The Zhao family originated from Zhuo Commandery (涿郡; Zhuó Jùn),[1] located near present-day Zhuozhou, Hebei Province in China, and traced its roots back to the Spring and Autumn period (roughly 771–476 BCE). The founder of the Song Empire, Zhao Kuangyin, was born to a military family. His father, Zhao Hongyin was a general in Zhuo Commandery who later moved to Luoyang with his family. Zhao Kuangyin also had an elder brother Zhao Guangji, two younger brothers Zhao Kuangyi and Zhao Guangmei, and two younger sisters.

Rise of the Zhao family

Zhao Kuangyin initially served in the Later Han military but he subsequently defected to serve under Chai Rong, emperor of Later Zhou, an enemy of the Later Han. He also persuaded his father, a Later Han general, to serve Chai Rong, thus contributing to the decline and collapse of the Later Han. Having gained Chai Rong's trust, Zhao Kuangyin was assigned as guardian to Chai Rong's seven-year-old son, Guo Zongxun, before Chai's death.

Zhao Kuangyin subsequently deposed Guo Zongxun in a bloodless military coup and established the Song dynasty. Following the founding of the dynasty, Zhao Kuangyin conquered the neighbouring states in the south and incorporated them into the fledgling empire. Fearing a military coup such as the one he instigated to depose Guo Zongxun, and to cement civilian power, Zhao Kuangyin dismissed his generals. This inadvertently weakened the military, which would have severe consequences in later years.

Zhao Kuangyin reigned for 17 years and died unexpectedly in 976, at the age of 49. His younger brother, Zhao Kuangyi (Emperor Taizong) succeeded him as the new emperor. It was suspected that Zhao Kuangyi murdered his brother, as well as two nephews, for the throne. The subsequent emperors – Emperor Zhenzong through Emperor Gaozong – were all descendants of Zhao Kuangyi, until Emperor Gaozong passed the throne to Zhao Shen (a descendant of Zhao Kuangyin), and adopted him as his son.

Decline after the Jingkang Incident

The Song Empire was prosperous during Zhao Kuangyi (Emperor Taizong)'s reign despite the threats posed by the northern nomadic empires, such as the Khitan-led Liao Empire, Jurchen-led Jin Empire and Tangut-led Western Xia. In 1115, the Song aligned themselves with the Jin regime in the hope of capturing the Sixteen Prefectures. However, this alliance allowed the Jurchens to learn of the Song's military weaknesses, namely a lack of capable commanders and armies primarily composed of mercenaries and poorly trained convicts. After the fall of the Liao empire, the Jin invaded Song territory and, on 20 March 1127, captured the Song capital, Bianjing (present-day Kaifeng). The Emperors Huizong and Qinzong, along with many family members, were captured and taken to the Jin capital, Shangjing, in present-day Harbin. This event is historically known as the Jingkang Incident. Many of these nobles died during the journey to, or after arriving in, Shangjing, although some committed suicide to avoid degradation at the hands of the Jurchens.[2]

Emperor Huizong's ninth son, Zhao Gou the future Emperor Gaozong, escaped from Bianjing and fled to southern China, where he reestablished the Song Empire (as the Southern Song dynasty) with its capital at Lin'an (present-day Hangzhou) and himself as the new emperor. As his own son had died prematurely, Emperor Gaozong designated Zhao Shen (Emperor Xiaozong), a descendant of Zhao Kuangyin (Emperor Taizu), as heir thus returning the imperial lineage to Zhao Kuangyin's line.

In 1234, the Song Empire allied with the Mongol Empire against the Jin Empire. While successful at bringing about the downfall of the Jin Empire, the alliance also exposed significant weaknesses in the Southern Song military to the Mongolians. Leading up to the alliance with the Mongol Empire, capable commanders, such as Yue Fei and Han Shizhong, had been able to reform the military in the years following the loss of the northern part of the empire, but imperial distrust hamstrung these commanders. Furthermore, the signing of the Treaty of Shaoxing resulted in the Song Empire becoming a vassal to the Jin Empire as well as the execution of Yue Fei, who commanded the armies that fought the Jin in former northern Song territories. Following the fall of the Jin Empire, the Mongol Empire acquired Chinese siege weaponry, cannons, and gunpowder-related weapons, which they used to further their conquests. The fall of the Jin Empire also ended the Song-Mongol alliance and an outbreak of hostilities between the former allies.

Fall of the Song Empire

Despite the weakness of the Song military, they managed to slow the Mongol Empire advance for decades. The Song resistance led to the death of Möngke Khan, in 1259, at Diaoyu Fortress. The resulting withdrawal of the Mongol forces, for the customary kurultai to select a new Khan, ultimately led to the Toluid Civil War which divided the Mongol Empire. Möngke's brother, Kublai Khan, who already controlled Mongolia and China's northern territories, formerly part of the Jin Empire, declared himself Emperor of China and founded the Yuan dynasty. Kublai renewed the Mongol campaign against the Song eventually capturing the fortified cities of Fancheng, and Xiangyang during the Battle of Xiangyang in 1273, allowing his armies to advance deep into Song territory and seize its capital. On 19 March 1279, the Song chancellor Lu Xiufu committed suicide with the eight-year-old Zhao Bing after the defeat of the remaining Song forces at the Battle of Yamen bringing an end to the Song Dynasty and marking the beginning of a century of Mongolian rule over China before the establishment of the Ming Dynasty by the House of Zhu and a return to Han rule.[3]

Descendants

Zhao Mengfu,[4][5] was a famous painter during the Yuan dynasty and met the Yuan emperor Kublai Khan on at least one occasion. He was the father of Zhao Yong and maternal grandfather of Wang Meng, both of whom were also accomplished scholars and painters.

The Southern Song Han Chinese Emperor Gong of Song (personal name Zhao Xian) surrendered to the Yuan dynasty Mongols in 1276 and was married off to a Mongol princess of the royal Borjigin family of the Yuan dynasty. Zhao Xian had one son with the Borjigin Mongol woman, Zhao Wanpu. Zhao Xian's son Zhao Wanpu was kept alive by the Mongols because of his mother's royal Mongolian Borjigin ancestry even after Zhao Xian was ordered killed by the Mongol Emperor Yingzong. Instead Zhao Wanpu was only moved and exiled. The outbreak of the Song loyalist Red Turban Rebellion in Henan led to a recommendation that Zhao Wanpu should be transferred somewhere else by an Imperial Censor in 1352. The Yuan did not want the Chinese rebels to get their hands on Zhao Wanpu so no one was permitted to see him and Zhao Wanpu's family and himself were exiled to Shazhou near the border by the Yuan Emperor. Paul Pelliot and John Andrew Boyle commented on Rashid-al-Din Hamadani's chapter The Successors of Genghis Khan in his work Jami' al-tawarikh, identified references by Rashid al-Din to Zhao Xian in his book where he mentions a Chinese ruler who was an "emir" and son-in-law to the Qan (Khan) after being removed from his throne by the Mongols and he is also called "Monarch of Song", or Suju (宋主 Songzhu) in the book.[6]

Other descendants include Zhao Yiguang (1559-1625), who lived during the Ming dynasty and a patron of the arts.[7] One recipient of his patronage was Lu Qingzi, an intellectual and a member of the scholar-gentry class, who he later married.[8][9] Zhao Yiguang and Lu had a son, Zhao Jun, who married the daughter of Wen Congjian, who also descended from a scholarly family.[10] Two works by Zhao Yiguang, Jiuhuan Shitu (九圜史圖) and Liuhe Mantu (六匌曼圖), which form part of the Siku Quanshu, were in a collection owned by Wang Qishu.[11]

The Zhao Imperial family survived into the Ming and Qing dynasties,[12][13][14] and on into the modern era where they have split into more than 20 different branches.[15] Descendants of the Song emperors are known to live in Chengcun Village near the Wuyi Mountains in Fujian Province,[16] while others reside in Hua'an County and Guangdong Province.

In 1351 anti-Yuan dynasty Red Turban rebel leaders Han Shantong and his son Han Lin'er (w:zh:韓林兒) claimed descent from the Song dynasty and Han Liner was enthroned as the Longfeng 龍鳳 Emperor of the Great Song dynasty (Red Turban Song dynasty w:zh:宋 (韓林兒)).[17]

In 1768 anti-Qing dynasty Tiandihui rebel Zhao Liangming claimed to be a descendant of the Song dynasty.[18][19]

Zhao Family Fort

Of particular importance to Zhao descendants is the Zhao Family Fort (趙家堡) in Zhangpu County, Fujian Province. The Fort was built after Zhao Ruohe (a descendant of Emperor Taizu and Emperor Taizong's brother Zhao Guangmei), his family and other members of the imperial clan fled to Zhangpu County after escaping Mongolian pursuit. Zhao Ruohe and his family were forced to change their family name to Huang to avoid discovery. Seventeen years after the end of the Yuan dynasty and the ascendancy of the Ming dynasty, a descendant of Zhao Ruohe, Huang Mingguan, became engaged to a woman whose surname was also Huang. This raised the suspicion of local law officials that the families may be committing to an incestuous union until the lineage of Huang Mingguan was revealed. Their residence was subsequently renamed. In later years, a Zhao descendant, Zhao Fan, entered politics in the Ming imperial court. After his retirement, Zhao Fan and his son, Zhao Yixiu, had the Fort renovated to match the architecture of Kaifeng prior to its capture by the Jin Empire.[20] In modern times, the fort has become a tourist attraction, displaying artifacts from the Song Dynasty, as well as a gathering place for the descendants of the Zhao family.

Family tree of emperors

The Generation poem used by the Zhao family was "若夫,元德允克、令德宜崇、師古希孟、時順光宗、良友彥士、登汝必公、不惟世子、與善之從、伯仲叔季、承嗣由同。"[21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29] The 42 characters were split into three groups of 14 for the offspring of Song Taizu and his two brothers.[30]

Notable members

- Song dynasty emperors

- Zhao Mengfu, Yuan dynasty artist

- Zhao Yong, artist, Zhao Mengfu's son

- Wang Meng, artist, Zhao Mengfu's maternal grandson

- Zhao Yiguang, Ming dynasty writer, related to Zhao Mengfu

Gallery

Emperor Huizong of Song (Poem and Calligraphy)

Emperor Huizong of Song (Poem and Calligraphy) Emperor Huizong of Song, Plum and Birds

Emperor Huizong of Song, Plum and Birds Emperor Huizong of Song, Golden Pheasant and Cotton Rose Flowers

Emperor Huizong of Song, Golden Pheasant and Cotton Rose Flowers Emperor Huizong of Song, Dragon Stone

Emperor Huizong of Song, Dragon Stone Emperor Huizong of Song, Cranes 1112

Emperor Huizong of Song, Cranes 1112 Emperor Huizong of Song, Classic Thousand-character Grass script

Emperor Huizong of Song, Classic Thousand-character Grass scriptHandscroll%2C_ink_and_colors_on_paper%2C_28.4_x_93.2_cm_National_Palace_Museum%2C_Taipei.jpg) Autumn colors on the Qiao and Hua mountains, by Zhao Mengfu

Autumn colors on the Qiao and Hua mountains, by Zhao Mengfu A Man and His Horse in the Wind, by Zhao Mengfu

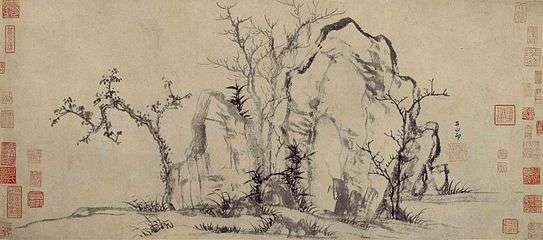

A Man and His Horse in the Wind, by Zhao Mengfu Elegant Rocks and Sparse Trees, by Zhao Mengfu

Elegant Rocks and Sparse Trees, by Zhao Mengfu A Sheep and Goat, by Zhao Mengfu

A Sheep and Goat, by Zhao Mengfu Old Tree and Horses, by Zhao Mengfu

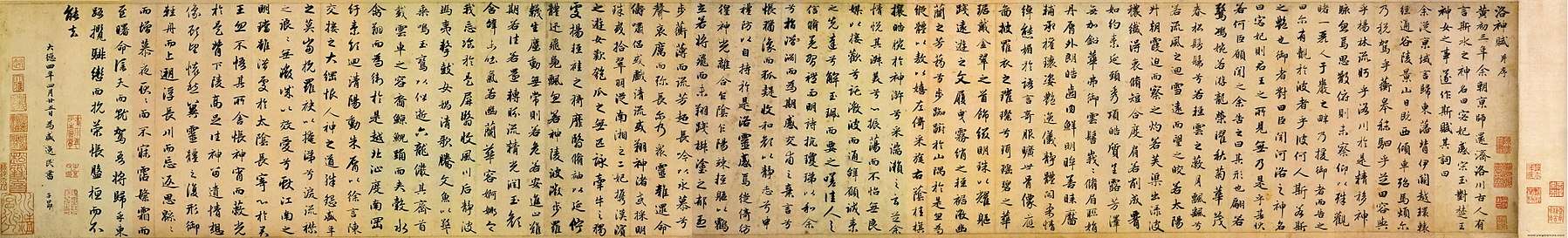

Old Tree and Horses, by Zhao Mengfu Zhao Mengfu writes the Tale of the Goddess of Luo River.

Zhao Mengfu writes the Tale of the Goddess of Luo River.

References

- 陳邦瞻【宋史紀事本末】卷一

- "Moaning Words" 宋人無名氏【呻吟語】

- Rossabi 1988, p. 76

- http://www.sino-platonic.org/complete/spp110_wuzong_emperor.pdf p. 15.

- John W. Chaffee (1999). Branches of Heaven: A History of the Imperial Clan of Sung China. Harvard Univ Asia Center. pp. 255–. ISBN 978-0-674-08049-2.

- Hua, Kaiqi (2018). "Chapter 6 The Journey of Zhao Xian and the Exile of Royal Descendants in the Yuan Dynasty (1271 1358)". In Heirman, Ann; Meinert, Carmen; Anderl, Christoph (eds.). Buddhist Encounters and Identities Across East Asia. Leiden, Netherlands: BRILL. p. 213. doi:10.1163/9789004366152_008. ISBN 978-9004366152.

- Dorothy Ko (1994). Teachers of the inner chambers: women and culture in seventeenth-century China. Stanford University Press. p. 270. ISBN 0-8047-2359-1.

- Ellen Widmer; Kang-i Sun Chang (1997). Ellen Widmer; Kang-i Sun Chang (eds.). Writing women in late imperial China (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 93. ISBN 0-8047-2872-0.

Lu Qingzi married a man who led an equally idyllic life, Zhao Yiguang (1559-1625 ), a descendant of the Song imperial family. Zhao fancied himself a recluse but often busied himself entertaining powerful and learned friends.

- Ellen Widmer, Kang-i Sun Chang (1997). Ellen Widmer, Kang-i Sun Chang (ed.). Writing women in late imperial China. Stanford University Press. p. 26. ISBN 0-8047-2872-0.

At age 15 sui, she married a literatus, Zhao Yiguang (zi Fanfu, 1559-1625) with whom she lived in seclusion in Hanshan.

- Marsha Smith Weidner (1988). Marsha Smith Weidner, Indianapolis Museum of Art (ed.). Views from Jade Terrace: Chinese women artists, 1300-1912. Indianapolis Museum of Art. p. 31. ISBN 0-8478-1003-8.

She married ZhaoJun, scion of an old Suzhou family, which traced its ancestry back to the imperial family of the Song dynasty and which counted among its sons the famous official and artist Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322). Zhao Jun's father was the recluse-scholar Zhao Yiguang (1559- 1625), and his mother was a daughter of Lu Shidao (1511-74), another Suzhou literatus. Zhao Jun studied the classics with Wen Congjian; thus a more permanent liaison between the two families was perhaps inevitable.

- Florence Bretelle-Establet (2010). Florence Bretelle-Establet (ed.). Looking at it from Asia: the processes that shaped the sources of history of science. Volume 265 of Boston studies in the philosophy of science (illustrated ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-90-481-3675-9.

- John W. Chaffee (1999). Branches of Heaven: A History of the Imperial Clan of Sung China. Harvard Univ Asia Center. pp. 16–. ISBN 978-0-674-08049-2.

- John W. Chaffee (1999). Branches of Heaven: A History of the Imperial Clan of Sung China. Harvard Univ Asia Center. pp. 20–. ISBN 978-0-674-08049-2.

- John W. Chaffee (1999). Branches of Heaven: A History of the Imperial Clan of Sung China. Harvard Univ Asia Center. pp. 247–. ISBN 978-0-674-08049-2.

- John W. Chaffee (1999). Branches of Heaven: A History of the Imperial Clan of Sung China. Harvard Univ Asia Center. pp. 272–. ISBN 978-0-674-08049-2.

- http://www.china.org.cn/english/culture/50676.htm

- Farmer, Edward L., ed. (1995). Zhu Yuanzhang and Early Ming Legislation: The Reordering of Chinese Society Following the Era of Mongol Rule. BRILL. p. 21, 23. ISBN 9004103910.

- Murray, Dian H.; Qin, Baoqi (1994). The Origins of the Tiandihui: The Chinese Triads in Legend and History. Stanford University Press. ISBN 080476610X.

- "Secret Societies" Reconsidered: Perspectives on the Social History of Modern South China and Southeast Asia. M.E. Sharpe. 1993. p. 185. ISBN 076564116X.

- "中國‧福建‧漳浦‧趙家堡(Zhangpu) @ confusingstone的部落格 :: 痞客邦 PIXNET". PIXNET Travel. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- "浙江趙建飛_新浪博客".

- 梁永樂、趙公梃 (1 July 2014). 八爪魚家長──孩子愛玩不是罪. 明窗. pp. 107–. ISBN 978-988-8287-38-3.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-07-29. Retrieved 2016-05-18.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "御制玉牒派序_赵氏社区,赵姓社区 - 百家姓 - 族谱录".

- "《天潢贵胄》试读:太祖的宗室定义".

- "这才是正宗的赵氏字辈,你们那都是被修改的!_赵氏吧_百度贴吧".

- "404页面".

- http://guangdong.kaiwind.com/yyfh/201506/02/t20150602_2547276.shtml

- John W. Chaffee (1999). Branches of Heaven: A History of the Imperial Clan of Sung China. Harvard Univ Asia Center. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-0-674-08049-2.

- Thomas H. C. Lee (January 2004). The New and the Multiple: Sung Senses of the Past. Chinese University Press. pp. 357–. ISBN 978-962-996-096-4.