Xolotl

In Aztec mythology, Xolotl (Nahuatl pronunciation: [ˈʃolot͡ɬ] (![]()

Myths and functions

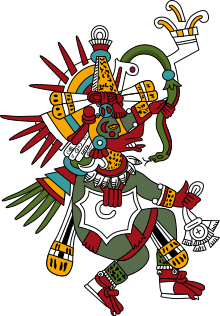

Xolotl was the sinister god of monstrosities who wears the spirally-twisted wind jewel and the ear ornaments of Quetzalcoatl.[5] His job was to protect the sun from the dangers of the underworld. As a double of Quetzalcoatl, he carries his conch-like ehecailacacozcatl or wind jewel. Xolotl accompanied Quetzalcoatl to Mictlan, the land of the dead, or the underworld, to retrieve the bones from those who inhabited the previous world (Nahui Atl) to create new life for the present world, Nahui Ollin, the sun of movement. In a sense, this re-creation of life is reenacted every night when Xolotl guides the sun through the underworld. In the tonalpohualli, Xolotl rules over day Ollin (movement) and over trecena 1-Cozcacuauhtli (vulture).[6]

His empty eye sockets are explained in the legend of Teotihuacan, in which the gods decided to sacrifice themselves for the newly created sun. Xolotl withdrew from this sacrifice and wept so much his eyes fell out of their sockets.[7] According to the creation recounted in the Florentine Codex , after the Fifth Sun was initially created, it did not move. Ehecatl ("God of Wind") consequently began slaying all other gods to induce the newly created Sun into movement. Xolotl, however, was unwilling to die in order to give movement to the new Sun. Xolotl transformed himself into a young maize plant with two stalks (xolotl), a doubled maguey plant (mexolotl), and an amphibious animal (axolotl). Xolotl is thus a master transformer. In the end, Ehecatl succeeded in finding and killing Xolotl.[8]

In art, Xolotl was typically depicted as a dog-headed man, a skeleton, or a deformed monster with reversed feet. An incense burner in the form of a skeletal canine depicts Xolotl.[9] As a psychopomp, Xolotl would guide the dead on their journey to Mictlan the afterlife in myths. His two spirit animal forms are the Xoloitzcuintli dog and the water salamander species known as the Axolotl.[10] Xolos served as companions to the Aztecs in this life and also in the after-life, as many dog remains and dog sculptures have been found in Aztec burials, including some at the main temple in Tenochtitlan. Dogs were often subject to ritual sacrifice so that they could accompany their master on his voyage through Mictlan, the underworld.[11] Their main duty was to help their owners cross a deep river. It is possible that dog sculptures also found in burials were also intended to help people on this journey. Xoloitzcuintli is the official name of the Mexican Hairless Dog (also known as perro pelón mexicano in Mexican Spanish), a pre-Columbian canine breed from Mesoamerica dating back to over 3500 years ago.[12] This is one of many native dog breeds in the Americas and it is often confused with the Peruvian Hairless Dog. The name "Xoloitzcuintli" references Xolotl because this dog's mission was to accompany the souls of the dead in their journey into eternity. The name "Axolotl" comes from Nahuatl, the Aztec language. One translation of the name connects the Axolotl to Xolotl. The most common translation is "water-dog" . "Atl" for water and "Xolotl" for dog.[13]

In the Aztec calendar, the ruler of the day, Itzcuintli ("Dog"), is Mictlantecuhtli, the god of death and lord of Mictlan, the afterlife.[14]

Origin

Xolotl is sometimes depicted carrying a torch in the surviving Maya codices, which reference the Maya tradition that the dog brought fire to mankind.[15] In the Mayan codices, the dog is conspicuously associated with the god of death, storm, and lightning.[16] Xolotl appears to have affinities with the Zapotec and Maya lightning-dog, and may represent the lightning which descends from the thundercloud, the flash, the reflection of which arouses the misconceived belief that lightning is "double", and leads them to suppose a connection between lightning and twins.[17]

Xolotl originated in the southern regions, and may represent fire rushing down from the heavens or light flaming up in the heavens.[18] Xolotl was originally the name for lightning beast of the Maya tribe, often taking the form of a dog.[7] The dog plays an important role in Maya manuscripts. He is the lightning beast, who darts from heaven with a torch in his hand.[19] Xolotl is represented directly as a dog, and is distinguished as the deity of air and of the four directions of the wind by Quetzalcoatl's breast ornament. Xolotl is to be considered equivalent to the beast darting from heaven of the Maya manuscript.[20] The dog is the animal of the dead and therefore of the Place of Shadows.[17]

.jpg) Dresden Codex Dog (p. 7)

Dresden Codex Dog (p. 7).jpg) Dog (p. 39)

Dog (p. 39).jpg) Dog (p. 40)

Dog (p. 40)

Ollin and Xolotl

_Day_symbol.jpg)

Eduard Seler associates Xolotl's portrayal as a dog with the belief that dogs accompany the souls of the dead to Mictlan. He finds further evidence of the association between Xolotl, dogs, death, and Mictlan in the fact that Mesoamericans viewed twins as unnatural monstrosities and consequently commonly killed one of the two twins shortly after birth. Seler speculates that Xolotl represents the murdered twin who dwells in the darkness of Mictlan, while Quetzalcoatl ("The Precious Twin") represents the surviving twin who dwells in the light of the sun.[8]

In manuscripts the setting sun, devoured by the earth, is opposite Xolotl's image.[21] Quetzalcoatl and Xolotl constitute the twin phases of Venus as the morning and evening star, respectively. Quetzalcoatl as the morning star acts as the harbinger of the Sun's rising (rebirth) every dawn, Xolotl as the evening star acts as the harbinger of the Sun's setting (death) every dusk. In this way they divide the single life-death process of cyclical transformation into its two phases: one leading from birth to death, the other from death to birth.[8]

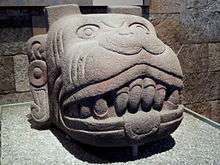

Xolotl was the patron of the Mesoamerican ballgame. Some scholars argue the ballgame symbolizes the Sun's perilous and uncertain nighttime journey through the underworld.[8] Xolotl is able to help in the Sun's rebirth since he possesses the power to enter and exit the underworld.[8] In several of the manuscripts Xolotl is depicted striving at this game against other gods. For example, in the Codex Mendoza we see him playing with the moon-god, and can recognize him by the sign ollin which accompanies him, and by the gouged-out eye in which that symbol ends. Seler thinks "that the root of the name ollin suggested to Mexicans the motion of the rubber ball olli and, as a consequence, ball-playing."[22]

Ollin is pulsating, oscillating, and centering motion-change. It is typified by bouncing balls, pulsating hearts, labor contractions, earthquakes, flapping butterfly wings, the undulating motion of weft activities in weaving, and the oscillating path of the Fifth Sun over and under the surface of the earth. Ollin is the motion-change of cyclical completion.[23]

A jade statue of a skeletal Xolotl carrying a solar disc bearing an image of the Sun on his back[24][25] (called "the Night Traveler") succinctly portrays Xolotl's role in assisting the Sun through the process of death, gestation, and rebirth. Xolotl's association with ollin motion-change suggests proper completions and gestations must instantiate ollin motion-change. Ollin-shaped decomposition and integration (i.e., death) promote ollin-shaped composition and integration (i.e., rebirth and renewal).[8]

Nanahuatzin and Xolotl

.jpg)

A close relationship between Xolotl and Nanahuatzin exists.[28] Xolotl is probably identical with Nanahuatl (Nanahuatzin).[29] Seler characterizes Nanahuatzin ("Little Pustule Covered One"), who is deformed by syphilis, as an aspect of Xolotl in his capacity as god of monsters, deforming diseases, and deformities.[8] The syphilitic god Nanahuatzin is an avatar of Xolotl.[30]

See also

Notes

- Johns 2008 p. 25

- Milbrath 2013 p. 83

- Milbrath 2013 p. 84

- Neumann 1975 p. 16

- Seler 2010 p. 290

- "Xolotl, the Twin". azteccalendar.com.

- Seler 2010 p. 94

- Maffie, James (2013). Aztec Philosophy: Understanding a World in Motion. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 1-45718-426-5. Olin and Xolotl

- "Xolotl (Illustration)". ancient.eu.

- "Story of the Fifth Sun". mexicolore.co.uk.

- "Dog". mexicolore.co.uk.

- "About Xolos". xoloitzcuintliclubofamerica.org.

- "Introduction". axolotl.org.

- "Mictlantecuhtli". azteccalendar.com.

- Neumann 1975 p. 19

- Johnson 1994 p. 118

- Spence 2015 p. 276

- Seler 2010 p. 65

- Seler 2010 p. 45

- Seler 2010 p. 46

- Seler 2010 p. 66

- Spence 2015 p. 275

- "Aztec Philosophy". mexicolore.co.uk.

- "Skeletonized deity". Latinamericastudies.org.

- "Statue of Xolotl, rear view". Gettyimages.com.

- Boone, Elizabeth Hill (2013). Cycles of Time and Meaning in the Mexican Books of Fate. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-75656-4.

- Milbrath 2013 p. 57

- Boone 1985 p. 132

- Spence 1994 p. 93

- Sweely 1999 p. 120

References

- Seler, Eduard (2010). Mexican And Central American Antiquities, Calendar Systems And History. translated by Charles P. Bowditch. Kessinger Publishing, LLC. ISBN 978-1-169-14785-0.

- Milbrath, Susan (2013). Heaven and Earth in Ancient Mexico: Astronomy and Seasonal Cycles in the Codex Borgia. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-74373-1.

- Neumann, Franke J. (1975). "The Dragon and the Dog: Two Symbols of Time in Nahuatl Religion". Numen, Vol. 22, Fasc. 1 Apr 1975. Brill Publishers: 1–23.

- Johns, Catherine (2008). Dogs: History, Myth, Art. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03093-0.

- Maffie, James (2013). Aztec Philosophy: Understanding a World in Motion. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 1-45718-426-5.

- Johnson, Buffie (1994). Lady of the Beasts: The Goddess and Her Sacred Animals. Inner Traditions International. ISBN 0-89281-523-X.

- Spence, Lewis (1994). The Myths and Legends of Mexico and Peru. Senate; New edition. ISBN 1-85958-007-6.

- Spence, Lewis (2015). The Magic and Mysteries of Mexico: Or the Arcane Secrets and Occult Lore of the Ancient Mexicans and Maya (Classic Reprint). Forgotten Books. ISBN 1-33045-827-3.

- Boone, Elizabeth Hill (1985). Painted Architecture and Polychrome Monumental Sculpture in Mesoamerica. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. ISBN 0-884-02142-4.

- Boone, Elizabeth Hill (2013). Cycles of Time and Meaning in the Mexican Books of Fate. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-75656-4.

- Sweely, Tracy L. (1999). Manifesting Power: Gender and the Interpretation of Power in Archaeology. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-415-17179-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Xolotl. |