Xipe Totec

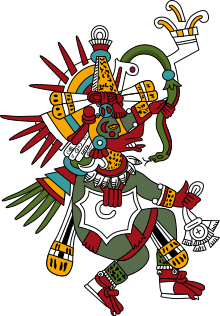

In Aztec mythology and religion, Xipe Totec (/ˈʃiːpə ˈtoʊtɛk/; Classical Nahuatl: Xīpe Totēc [ˈʃiːpe ˈtoteːkʷ]) or Xipetotec[1] ("Our Lord the Flayed One")[2] was a life-death-rebirth deity, god of agriculture, vegetation, the east , spring, goldsmiths, silversmiths, liberation and the seasons.[3] Xipe Totec was also known by various other names, including Tlatlauhca (Nahuatl pronunciation: [t͡ɬaˈt͡ɬawʔka]), Tlatlauhqui Tezcatlipoca (Nahuatl pronunciation: [t͡ɬaˈt͡ɬawʔki teskat͡ɬiˈpoːka]) ("Red Smoking Mirror") and Youalahuan (Nahuatl pronunciation: [jowaˈlawan]) ("the Night Drinker").[4] The Tlaxcaltecs and the Huexotzincas worshipped a version of the deity under the name of Camaxtli,[5] and the god has been identified with Yopi, a Zapotec god represented on Classic Period urns.[6] The female equivalent of Xipe Totec was the goddess Xilonen-Chicomecoatl.[7]

Xipe Totec connected agricultural renewal with warfare.[8] He flayed himself to give food to humanity, symbolic of the way maize seeds lose their outer layer before germination and of snakes shedding their skin. Without his skin, he was depicted as a golden god. Xipe Totec was believed by the Aztecs to be the god that invented war.[9] His insignia included the pointed cap and rattle staff, which was the war attire for the Mexica emperor.[10] He had a temple called Yopico within the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan.[6] Xipe Totec is associated with pimples, inflammation and eye diseases,[11][12] and possibly plague.[13] Xipe Totec has a strong relation to diseases such as smallpox, blisters and eye sickness[14] and if someone suffered from these diseases offerings were made to him.[15]

This deity is of uncertain origin. Xipe Totec was widely worshipped in central Mexico at the time of the Spanish Conquest,[6] and was known throughout most of Mesoamerica.[16] Representations of the god have been found as far away as Mayapan in the Yucatán Peninsula.[17] The worship of Xipe Totec was common along the Gulf Coast during the Early Postclassic. The deity probably became an important Aztec god as a result of the Aztec conquest of the Gulf Coast in the middle of the fifteenth century.[6]

In January 2019, Mexican archaeologists from the National Institute of Anthropology and History confirmed that they had discovered the first known surviving temple dedicated to Xipe Totec in the Puebla state of Mexico.[18] The temple was found while examining ruins of the Popoluca peoples indigenous to Mexico. The Popolucas built the temple in an area called Ndachjian-Tehuacan between AD 1000 and 1260 prior to Aztec invasion of the area.[19]

Attributes

Xipe Totec appears in codices with his right hand upraised and his left hand extending towards the front.[21] Xipe Totec is represented wearing flayed human skin, usually with the flayed skin of the hands falling loose from the wrists.[22] His hands are bent in a position that appears to possibly hold a ceremonial object.[23] His body is often painted yellow on one side and tan on the other.[22] His mouth, lips, neck, hands and legs are sometimes painted red. In some cases, some parts of the human skin covering is painted yellowish-gray. The eyes are not visible, the mouth is open and the ears are perforated.[23] He frequently had vertical stripes running down from his forehead to his chin, running across the eyes.[6] He was sometimes depicted with a yellow shield and carrying a container filled with seeds.[24] One Xipe Totec sculpture was carved from volcanic rock, and portrays a man standing on a small pedestal. The chest has an incision, made in order to extract the heart of the victim before flaying. It is likely that sculptures of Xipe Totec were ritually dressed in the flayed skin of sacrificial victims and wore sandals.[25][26] In most of Xipe Totec sculptures, artists always make emphasis in his sacrificial and renewal nature by portraying the different layers of skin.

Symbolism

Xipe Totec emerging from rotting, flayed skin after twenty days symbolised rebirth and the renewal of the seasons, the casting off of the old and the growth of new vegetation.[14] New vegetation was represented by putting on the new skin of a flayed captive because it symbolized the vegetation the earth puts on when the rain comes.[27] The living god lay concealed underneath the superficial veneer of death, ready to burst forth like a germinating seed.[28] The deity also had a malevolent side as Xipe Totec was said to cause rashes, pimples, inflammations and eye infections.[14]

The flayed skins were believed to have curative properties when touched and mothers took their children to touch such skins in order to relieve their ailments.[29] People wishing to be cured made offerings to him at Yopico.[6]

Annual festival

The annual festival of Xipe Totec was celebrated on the spring equinox before the onset of the rainy season; it was known as Tlacaxipehualiztli ([t͡ɬakaʃipewaˈlist͡ɬi]; lit. "flaying of men").[30] This festival took place in March at the time of the Spanish Conquest.[31] Forty days before the festival of Xipe Totec, a slave who was captured at war was dressed to represent the living god who was honored during this period. This occurred in every ward of the city, which resulted in multiple slaves being selected.[32] The central ritual act of "Tlacaxipehualiztli" was the gladiatorial sacrifice of war prisoners, which both began and culminated the festival.[33] On the next day of the festival, the game of canes was performed in the manner of two bands. The first band were those who took the part of Xipe Totec and went dressed in the skins of the war prisoners who were killed the previous day, so the fresh blood was still flowing. The opposing band was composed of daring soldiers who were brave and fearless, and who took part in the combat with the others. After the conclusion of this game, those who wore the human skins went around throughout the whole town, entering houses and demanding that those in the houses give them some alms or gifts for the love of Xipe Totec. While in the houses, they sat down on sheaves of tzapote leaves and put on necklaces which were made of ears of corn and flowers. They had them put on garlands and give them pulque to drink, which was their wine.[34] Annually, slaves or captives were selected as sacrifices to Xipe Totec.[35] After having the heart cut out, the body was carefully flayed to produce a nearly whole skin which was then worn by the priests for twenty days during the fertility rituals that followed the sacrifice.[35] This act of putting on new skin was a ceremony called 'Neteotquiliztli' translating to "impersonation of a god".[36] The skins were often adorned with bright feathers and gold jewellery when worn.[37] During the festival, victorious warriors wearing flayed skins carried out mock skirmishes throughout Tenochtitlan, they passed through the city begging alms and blessed whoever gave them food or other offerings.[6] When the twenty-day festival was over, the flayed skins were removed and stored in special containers with tight-fitting lids designed to stop the stench of putrefaction from escaping. These containers were then stored in a chamber beneath the temple.[38]

The goldsmiths also participated in Tlacaxipehualizti. They had a feast called Yopico every year in the temple during the month of Tlacaxipehualizti. A satrap was adorned in the skin taken from one of the captives in order to appear like Xipe Totec. On the dress, they put a crown made of rich feathers, which was also a wig of false hair. Gold ornaments were put in the nose and nasal septum. Rattles were put in the right hand and a gold shield was put in the left hand, while red sandals were put on their feet decorated with quail-feathers. They also wore skirts made of rich feathers and a wide gold necklace. They were seated and offered Xipe Totec an uncooked tart of ground maize, many ears of corn that had been broken apart in order to get to the seeds, along with fruits and flowers. The deity was honored with a dance and ended in a war exercise.[39]

Human sacrifice

Various methods of human sacrifice were used to honour this god. The flayed skins were often taken from sacrificial victims who had their hearts cut out, and some representations of Xipe Totec show a stitched-up wound in the chest.[40]

"Gladiator sacrifice" is the name given to the form of sacrifice in which an especially courageous war captive was given mock weapons, tied to a large circular stone and forced to fight against a fully armed Aztec warrior. As a weapon he was given a macuahuitl (a wooden sword with blades formed from obsidian) with the obsidian blades replaced with feathers.[41] A white cord was tied either around his waist or his ankle, binding him to the sacred temalacatl stone.[42] At the end of the Tlacaxipehualiztli festival, gladiator sacrifice (known as tlauauaniliztli) was carried out by five Aztec warriors; two jaguar warriors, two eagle warriors and a fifth, left-handed warrior.[40]

"Arrow sacrifice" was another method used by the worshippers of Xipe Totec. The sacrificial victim was bound spread-eagled to a wooden frame, he was then shot with many arrows so that his blood spilled onto the ground.[41] The spilling of the victim's blood to the ground was symbolic of the desired abundant rainfall, with a hopeful result of plentiful crops.[43] After the victim was shot with the arrows, the heart was removed with a stone knife. The flayer then made a laceration from the lower head to the heels and removed the skin in one piece. These ceremonies went on for twenty days, meanwhile the votaries of the god wore the skins.[44]

Another instance of sacrifice was done by a group of metalworkers who were located in the town of Atzcapoatzalco, who held Xipe Totec in special veneration.[45] Xipe was a patron to all metalworkers (teocuitlapizque), but he was particularly associated with the goldsmiths.[46] Among this group, those who stole gold or silver were sacrificed to Xipe Totec. Before this sacrifice, the victims were taken through the streets as a warning to others.[45]

Other forms of sacrifice were sometimes used; at times the victim was cast into a firepit and burned, others had their throats cut.[41]

Notes

- Robelo 1905, p. 768.

- Marshall Saville, 1929, p. 155.

- Fernández 1992, 1996, pp.60-63. Matos Moctezuma 1988, p.181. Matos Moctezuma & Solis Olguín 2002, pp.54-5. Neumann 1976, pp.252.

- Fernández 1992, 1996, p.60. Neumann 1976, p.255.

- Fernández 1992, 1996, p.60-1.

- Miller & Taube 1993, 2003, p.188.

- Matos Moctezuma & Solis Olguín 2002, p.426.

- Evans and Webster 2001, p. 107.

- Matos Moctezuma & Solis Olguín 2002, p.423.

- Toby Evans & David Webster, 2001, p.107

- Susan Toby Evans; David L. Webster (11 September 2013). Archaeology of Ancient Mexico and Central America: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 218. ISBN 978-1-136-80185-3.

- http://www.ancient.eu/Xipe_Totec/

- Bob Curran; Ian Daniels (2007). Walking with the Green Man: Father of the Forest, Spirit of Nature. Career Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-56414-931-2.

- Fernández 1992, 1996, p.62.

- Citing Bernardino de Sahagún:O., Anderson, Arthur J.; E., Dibble, Charles (1970-01-01). General history of the things of New Spain : Book I, the Gods. School of American Research. ISBN 9780874800005. OCLC 877854386.

- Fernández 1992, 1996, p.60.

- Milbrath & Peraza Lope 2003, pp.19, 23, 26.

- Wade, Lizzie, Archaeologists have found a temple to the ‘Flayed Lord’ in Mexico, Science, January 4, 2019

- "Mexican experts discover first temple of god depicted as skinned human corpse".

- Museo de América.

- Marshall Saville, 1929, p.155.

- Fernández 1992, 1996, p.60. Matos Moctezuma & Solis Olguín 2002, p.422.

- Marshall H. Saville 1929, p.156.

- Matos Moctezuma & Solis Olguín 2002, p.468.

- Matos Moctezuma & Solis Olguín 2002, p.171.

- Marshall H. Saville 1929, p.155.

- Michael D. Coe & Rex Koontz 1962, 1977, 1984, 1994, 2002, 2008, p.207.

- Matos Moctezuma & Solis Olguín 2002, p.324

- Matos Moctezuma 1988, p.188.

- Marshall Saville, p. 167.

- Matos Moctezuma & Solis Olguín 2002, pp.422, 468. Smith 1996, 2003, p.252.

- Marshall Saville, 1929, p. 171.

- Franke J. Neumann 1976, p. 254. Matos Moctezuma & Solis Olguín 2002, p.422. Miller & Taube 1993, 2003, p.188.

- Marshall Saville, 1929, p. 167-168.

- Matos Moctezuma & Solis Olguín 2002, p.422

- Franke J. Neumann 1976, p. 254.

- Matos Moctezuma & Solis Olguín 2002, p.478

- Matos Moctezuma & Solis Olguín 2002, p.423

- Marshall Saville, 1929, p. 169-170.

- Matos Moctezuma & Solis Olguín 2002, p.422.

- Smith 1996, 2003, p.218.

- Matos Moctezuma & Solis Olguín 2002, p.451-2.

- Marshall Saville, 1929, p.164.

- Marshall Saville, 1929, p.173-174.

- Marshall Saville, 1929, p.165.

- Franke J. Neumann 1976, p. 255.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Xipe Totec. |

- Coe, Michael D.; Koontz, Rex (2008) [1962]. Mexico From the Olmecs to the Aztecs. New York, New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28755-2. OCLC 2008901003.

- Evans, Toby & Webster, David (2001). Archaeology of Ancient Mexico and Central American Encyclopedia. New York: Garland Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8153-0887-4.

- Fernández, Adela (1996) [1992]. Dioses Prehispánicos de México (in Spanish). Mexico City: Panorama Editorial. ISBN 978-968-38-0306-1. OCLC 59601185.

- Matos Moctezuma, Eduardo (1988). The Great Temple of the Aztecs: Treasures of Tenochtitlan. New Aspects of Antiquity series. Doris Heyden (trans.). London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-27752-2. OCLC 17968786.

- Matos Moctezuma, Eduardo; Felipe Solis Olguín (2002). Aztecs. London: Royal Academy of Arts. ISBN 978-1-903973-22-6. OCLC 56096386.

- Milbrath, Susan; Carlos Peraza Lopez (2003). "Revisiting Mayapan: Mexico's last Maya capital". Ancient Mesoamerica. Cambridge University Press. 14: 1–46. doi:10.1017/s0956536103132178.

- Miller, Mary; Karl Taube (2003) [1993]. An Illustrated Dictionary of the Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-27928-1. OCLC 28801551.

- Museo de América. "Museo de América (Catalogue - item 1991/11/48)" (in Spanish). Madrid, Spain: Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. Retrieved 2012-06-15.

- Neumann, Franke J. (February 1976). "The Flayed God and His Rattle-Stick: A Shamanic Element in Pre-Hispanic Mesoamerican Religion". History of Religions. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. 15 (3): 251–263. doi:10.1086/462746.

- Robelo, Cecilio Agustín (1905). Diccionario de Mitología Nahua (in Spanish). Mexico City, Mexico: =Biblioteca Porrúa. Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Historia y Etnología. ISBN 978-9684327955.

- Saville, Marshall (1929). "Saville 'Aztecan God Xipe Totec". Indian Notes(1929). Museum of the American Indian: 151–174.

- Smith, Michael E. (2003) [1996]. The Aztecs (second ed.). Malden MA; Oxford and Carlton, Australia: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-23016-8. OCLC 59452395.

Further reading

- Mencos, Elisa (2010). B. Arroyo; A. Linares; L. Paiz (eds.). "Las representaciones de Xipe Totec en la frontera sur Mesoamericana" [The Representations of Xipe Totec on the southern frontier of Mesoamerica] (PDF). XXIII Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 2009 (in Spanish). Guatemala City: Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología: 1259–1266. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-11-03. Retrieved 2012-07-07.

- Pareyon, Gabriel (2006). "La música en la fiesta del dios Xipe Totec" (PDF). Proceedings of the 3rd National Forum of Mexican Music, 3 (2007) (in Spanish). Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas: 2–17. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 20, 2011.