Hestercombe House

Hestercombe House is a historic country house in the parish of West Monkton in the Quantock Hills, near Taunton in Somerset, England. The house is a Grade II* listed building and the estate is Grade I listed on the English Heritage Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in England.[3]

| Hestercombe House | |

|---|---|

Hestercombe House | |

| Location | West Monkton, Somerset, England |

| Coordinates | 51°03′11″N 3°05′03″W |

National Register of Historic Parks and Gardens | |

| Official name: Hestercombe | |

| Designated | 1 June 1984[1] |

| Reference no. | 1000437 |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

| Official name: Hestercombe House | |

| Designated | 17 May 1985[2] |

| Reference no. | 1060513 |

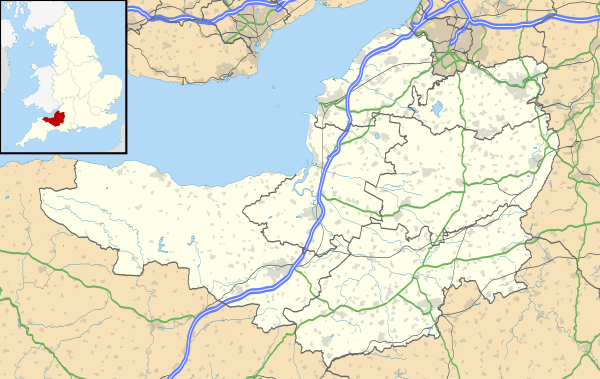

Location of Hestercombe House in Somerset | |

Originally built in the 16th century, the house was used as the headquarters of the British 8th Corps in the Second World War. Somerset County Council assumed ownership in 1951 and use the property as an administrative centre. Hestercombe House served as the Emergency Call Centre for the Somerset Area of Devon and Somerset Fire and Rescue Service until March 2012.[2]

Hestercombe House is surrounded by gardens which have been restored to Gertrude Jekyll's original plans (1904–07) and have made it "one of the best Jekyll-Lutyens gardens open to the public on a regular basis",[4] visited by approximately 70,000 people per year. The site also includes a 0.08 hectare (8,600 sq ft) biological Site of Special Scientific Interest in Somerset, notified in 2000. The site is used as a roost site by Lesser horseshoe bats.

Location

Hestercombe House is between West Monkton and Cheddon Fitzpaine in the Taunton Deane area in the south of the English county of Somerset. It is on the Quantock Hills which were England’s first Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty being designated in 1956.[5] The south facing gardens offer views of the Blackdown Hills.[6]

History

In the 11th century Hestercombe was owned by Glastonbury Abbey. Sir John Meriet founded a chantry in the 14th century and in 1392 it passed to John La Ware by marriage and stayed in his family for almost four hundred years.[1] The current house is a Grade II* listed[7] country house which was originally built in the 16th century for the Warre family. Sir Richard Warre (d. 1601) bequeathed it to his son Roger who married Elinor, daughter of Sir John Popham.[8] When their descendant Sir Francis Warre, Bt. died in 1718 he left the estate to his daughter, Margaret, who transferred it to her husband John Bampfylde (1691–1750). Following his death in 1750 it was inherited by the couple's son, Coplestone Warre Bampfylde, a landscape painter who developed pleasure grounds to the north of the house incorporating cascades, lakes and a series of ornamental structures.[9]

The house was enlarged and altered in the 18th century, but this work is no longer visible beneath the refronting and enlargement works carried out around 1875 for Edward Portman, 1st Viscount Portman, who had acquired it in 1873.[10][11]

Second World War

During the early years of the Second World War, the house and gardens were used by the British Army as part of the headquarters for VIII Corps, which was formed to command the defence of Somerset, Devon, Cornwall and Bristol. The VIII Corps main headquarters was at nearby Pyrland Hall, and the rear headquarters established at Hestercombe House, with Personnel and Logistics staff. Hestercombe was the headquarters of the American army 398th General Service Engineer Regiment from July 1943 to April 1944. Eisenhower visited Hestercombe on 18 March 1944 to meet General Gerow and inspect the troops. The Engineers were joined by the 19th District Headquarters of the US Supply Services in July 1943, which stayed until July 1944.[12]

Early on 28 March 1944, a few minutes after midnight, a Junkers Ju 88 crashed on the drive to the house after being shot down by cannon fire from a de Havilland Mosquito of No. 219 Squadron Royal Air Force. Hestercombe was the American 801 Hospital Centre after the Normandy landings until the end of the war.[12] A total of 33 barrack huts (various Nissen huts, Romney huts and MOWB (Ministry of Works brick huts) were constructed at Hestercombe during the war. Many were demolished in the 1960s by the Crown Estate, and only one is left standing, in Rook Wood.[13]

Post war

The house remained in the Portman family until 1944 when it was accepted in lieu of death duties by the Crown Estate, however Mrs Portman remained at the house until her death in 1951. It was leased to the fire service in 1953.[14] A visitor centre opened in the Victorian stables in 2005. Most of the cost of the conversion was funded by a grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund.[15] The house was used as the Emergency Call Centre for the Somerset Area of Devon and Somerset Fire and Rescue Service with a running cost in 2011 of £675,000 per year.[16] The fire service moved out in 2012 and restoration work was then undertaken.[17]

The house today appears an assemblage of several architectural styles popular during the Victorian era. While the overall design and air could be described as Italianate, also present in the same entrance facade are examples of high Victorian Gothic, such as an Italianate seigneurial tower confused in design with a campanile tower.[2] This tower complete with a glazed loggia is crowned by a French-style mansard roof with oversized chimneys masquerading as Renaissance ornament. The centrepiece of the same facade is a porte-cochère designed in a heavy neoclassical style.[18]

Watermill and dynamo house

In the 18th century a watermill was installed and used to power a sawmill, grind corn and crush apples. There is some evidence that there has been a mill on the site since the late 14th century.[19] The overshot waterwheel, which was 11 feet (3.4 m) in diameter and 4 feet (1.2 m) wide overall,[20] was replaced in 1895,[21] when the attached barn and workshops were expanded.[19] and generated electricity for the estate, which was stored in glass batteries. The waterwheel had deteriorated by the 1980s.[22]

From the 1950s until 2009 the buildings were used as a barn for animals and agricultural machinery. It has since been restored and had a biomass boiler installed. During the restoration an unexplained series of unusual pipework was discovered in the floor of the building.[23] The building now acts as a visitor centre,[19] which includes access to the dynamo room where acetylene gas was produced along with a thermalume generator which produced gas from petrol and air.[24]

Gardens

| Site of Special Scientific Interest | |

.jpg) | |

| Area of Search | Somerset |

|---|---|

| Grid reference | ST242287 |

| Interest | Biological |

| Area | 0.08 hectare (8,600 sq ft) |

| Notification | 2000 |

When the house and gardens were inherited by Coplestone Warre Bampfylde (1720–91) in the 18th century, a Georgian landscape garden was laid out, containing ponds, a grand cascade, a gothic alcove, a Tuscan temple arbour (1786),[25] and a folly mausoleum.[26] Bampfylde was an amateur architect of talent and a friend and adviser to Henry Hoare who laid out the gardens at Stourhead. Bampfylde also designed a Doric temple for the grounds, which was built around 1786,[27][25] with an ashlar tetrastyle prostyle fronted by Tuscan columns and a large modillioned pediment.[28] A Victorian formal parterre was added near the house by Henry Hall in the 1870s.[29]

The Edwardian garden was laid out by Gertrude Jekyll and Edwin Lutyens between 1904 and 1906 for the Hon E.W.B. Portman,[30][31] resulting in a garden "remarkable for the bold, concise pattern of its layout, and for the minute attention to detail everywhere to be seen in the variety and imaginative handling of contrasting materials, whether cobble, tile, flint, or thinly coursed local stone".[32] Jekyll and Lutyens were leading participants of the Arts and Crafts movement. Jekyll is remembered for her outstanding designs and subtle, painterly approach to the arrangement of the gardens she created, particularly her "hardy flower borders".[33] Jekyll was one of the first of her profession to take into account the colour, texture, and experience of gardens as the prominent authorities in her designs, and she was a lifelong fan of plants of all genres. Her theory of how to design with colour was influenced by painter J. M. W. Turner and by impressionism, and by the theoretical colour wheel. Their collaborative style was first developed at Herstercombe and described by the garden writer and designer Penelope Hobhouse as:

The collaboration between the architect Edwin Lutyens and Gertrude Jekyll was the teacher for a generation that was on the verge of imminent with the First World War abyss, the epitome of good taste and perfection. Architecture and planting strategy created together aesthetic and horticultural works, few of which have been preserved in their original state, but their influence lasting effect in countless gardens.[34]

The "Great Plat" combined the patterned features of a parterre with the hardy herbaceous planting espoused by Miss Jekyll.[31][35] Lutyens also designed the orangery about 50 m east of the main house between 1904–09,[36] which is now Grade I listed,[37] as are the garden walls, paving and steps on the south front of the house.[38] On either side of the Great Plat are raised terraces with brick water channels. In his 2018 BBC series Paradise Gardens, Monty Don suggested that the garden had many features of the traditional Islamic Paradise Garden.[39]

The eastern area is laid out as a Dutch garden laid out with perennial plants such as Large white flowering Yucca gloriosa as groups used vertical elements alternate with purple colored flowering dwarf Lavender (Lavandula), catmint (Nepeta) or silvery colored Zieste (Stachys), Cotton lavender (Santolina), China Rose (Rosa chinensis) or Fuchsia (Fuchsia magellanica).[40]

Since October 2003, the landscape and gardens, extending to over 100 acres (0.40 km2), have been managed by the Hestercombe Gardens Trust,[41] a registered charity set up to restore and preserve the site with a Heritage Lottery Fund grant of £3.7M.[42] The gardens featured on BBC TV's Gardens Through Time series,[43] and cover more than 40 acres (160,000 m2), with three different styles of garden ranging from woodland walks to lakes and ponds to formal gardens. The Georgian landscape, Victorian shrubbery and terrace and the formal Edwardian gardens combine to create biodiversity and interest for visitors. The site is used by Lesser horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus hipposideros) as both a breeding and wintering roost site. Numbers of Lesser Horseshoes at this site are only exceeded by one other site in southwest England. The bats use roofspaces in a former stable block as a maternity site.[44] It has been designated as a Special Area of Conservation (SAC).[45]

References

- Historic England. "Hestercombe (1000437)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- Historic England. "Hestercombe House (1060513)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- "Hestercombe Gardens" (PDF). European Garden Heritage network. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- "Somerset". GardenVist.com. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- "Quantock Hills" (PDF). Quantock Hills AONB. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- "Hestercombe Gardens". Swandown. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- Historic England. "Hestercombe House (1060513)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- Rice 2005, p. 35.

- Thomas 1874, p. 28.

- "Buildings". Hestercombe House. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- "Hestercombe, Taunton, England". Parks & Gardens UK. Parks and Gardens Data Services Ltd.

- Wakefield 1994, p. 101.

- "Gardens". Herstercombe House. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- "The restoration of the Formal Garden at Hestercombe 1973 to 1980 Part 1 – In the hands of the Fire Service". Parks and Gardens UK. Parks and Gardens Data Services. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- "Hestercombe Gardens Trust Update". Garden History Society. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- "Hestercombe House fire control could move to Exeter". This is the westcountry. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- "Philip White — Hestercombe's restoration man". Country Gardener. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- Marsh, Michael (6 March 2012). "Photos show history of Hestercombe House as summer handover nears". Somerset County Gazette. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- "Hestercombe Watermill". Mills archive. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- "Hestercombe House". Bulletin 111 – News and Notes. Somerset Industrial Archaeological Society. Archived from the original on 4 May 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- "Restoration at Hestercombe". Quantock Eco. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- Historic England. "Barn complex including pumping house and waterwheel (1308064)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- Murless, Brian; Warren, Derrick (2009). "Hestercombe sawmill, electric power and a mystery" (PDF). Industrial archeology news. 150: 12. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- "Watermill and barn". Hestercombe. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- Colvin 1995, p. ?.

- Historic England. "The Mausoleum in the grounds of Hester combe House (1060461)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- Bond 1998, p. 87.

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1390976)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- "Hestercombe, Taunton, England". Parks & Gardens UK. Parks and Gardens Data Services Limited (PGDS). Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- Historic England. "Garden walls, paving and steps on the south front of Hestercombe House (1060514)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- Brown 1982, pp. 15, 78, 83–85, 179, 184, 186.

- Goode et al. 2001.

- Bisgrove 1992, pp. 90-96.

- Hobhouse 2002.

- Brown 1992, p. 161.

- Waite 1964, p. 46.

- Historic England. "Orangery (1175994)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- Historic England. "Garden, walls, paving and steps on South front of Hestercombe House (1060514)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- "Monty Don's Paradise Gardens - BBC Two". BBC. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- "Gertrude Jekyll and Hestercombe,". English Heritage. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- Charity Commission. HESTERCOMBE GARDENS TRUST LIMITED, registered charity no. 1060000.

- "Hestercombe Garden's Philip White awarded MBE for services to heritage garden restoration". Somerset Life. 13 February 2013. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- "Episode 23". Gardeners World. BBC. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- "Hestercombe House" (PDF). SSSI Citation sheet. English Nature. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- "Hestercombe House". Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

Bibliography

- Bisgrove, Richard (1992). The Gardens of Gertrude Jekyll. Frances Lincoln. ISBN 978-0711207462.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bond, James (1998). Somerset Parks and Gardens. Somerset Books. ISBN 978-0-86183-465-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brown, Jane (1982). Gardens of a Golden Afternoon: The Story of a Partnership, Edwin Lutyens & Gertrude Jekyll. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. ISBN 978-0-7139-1440-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Colvin, Howard. A Biographical Dictionary of British Architects 1600–1840. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12508-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bisgrove, Richard (1992). The Gardens of Gertrude Jekyll. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-7112-0746-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goode, Patrick; Lancaster, Michael; Jellicoe, Geoffrey; Jellicoe, Susan (2001). The Oxford Companion to Gardens. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860440-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hobhouse, Penelope (2002). The Story of Gardening. Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-0751333909.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hugo, Thomas (1874). The History of Hestercombe, in the Parish of Kingston.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rice, Douglas Walthew (2005). The Life and Achievements of Sir John Popham, 1531–1607: Leading to the Establishment of the First English Colony in New England. Cranbury, New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4060-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Waite, Vincent (1964). Portrait of the Quantocks. London: Robert Hale. ISBN 0-7091-1158-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wakefield, Ken (1994). Operation Bolero: The Americans in Bristol and the West Country 1942–45. Crecy Books. ISBN 0-947554-51-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to |

- Hestercombe Gardens

- Parks & Gardens UK: Hestercombe, Taunton, England Bibliography.

- YouTube video — commemoration of WW2 activity, views of gardens.