STS-41-D

STS-41-D was the 12th flight of NASA's Space Shuttle program, and the first mission of Space Shuttle Discovery. It was launched from Kennedy Space Center, Florida, on 30 August 1984, and landed at Edwards Air Force Base, California, on 5 September. Three commercial communications satellites were deployed into orbit during the six-day mission, and a number of scientific experiments were conducted.

The launch of Space Shuttle Discovery on its first mission on 30 August 1984. | |

| Mission type | Satellite deployment |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID | 1984-093A |

| SATCAT no. | 15234 |

| Mission duration | 6 days, 00 hours, 56 minutes, 04 seconds |

| Distance travelled | 4,010,000 kilometres (2,490,000 mi) |

| Orbits completed | 97 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Space Shuttle Discovery |

| Launch mass | 119,511 kilograms (263,477 lb) |

| Landing mass | 91,478 kilograms (201,674 lb) |

| Payload mass | 18,681 kilograms (41,184 lb) |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 6 |

| Members |

|

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 30 August 1984, 12:41:50 UTC |

| Launch site | Kennedy LC-39A |

| End of mission | |

| Landing date | 5 September 1984, 13:37:54 UTC |

| Landing site | Edwards Runway 17 |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

| Perigee altitude | 346 kilometres (187 nmi) |

| Apogee altitude | 354 kilometres (191 nmi) |

| Inclination | 28.5 degrees |

| Period | 90.6 min |

| Epoch | 1 September 1984[1] |

Back row: L-R: Walker, Resnik Front row L-R: Mullane, Hawley, Hartsfield, Coats | |

The mission was delayed by more than two months from its original planned launch date, having experienced the Space Shuttle program's first launch abort at T-6 seconds on 26 June 1984.

Crew

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Henry W. Hartsfield Jr. Second spaceflight | |

| Pilot | Michael L. Coats First spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 1 | Richard M. Mullane First spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 2 | Steven A. Hawley First spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 3 | Judith A. Resnik First spaceflight | |

| Payload Specialist 1 | Charles D. Walker First spaceflight | |

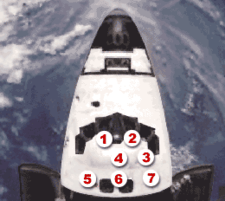

Crew seat assignments

| Seat[2] | Launch | Landing |  Seats 1–4 are on the Flight Deck. Seats 5–7 are on the Middeck. |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Hartsfield | Hartsfield | |

| S2 | Coats | Coats | |

| S3 | Mullane | Resnik | |

| S4 | Hawley | Hawley | |

| S5 | Resnik | Mullane | |

| S6 | Walker | Walker | |

Mission background

The launch was originally planned for 25 June 1984, but because of a variety of technical problems, including rollback to the Vehicle Assembly Building to replace a faulty main engine, the launch was delayed by over two months. The 26 June launch attempt marked the first time since Gemini 6A that a crewed spacecraft had experienced a shutdown of its engines just prior to launch.

June launch attempt

During the 26 June launch attempt, there was a launch abort at T-6 seconds, followed by a pad fire about ten minutes later.[3][4]

Commentary: "We have a cut off."

"NTD we have a RSLS (Redundant Set Launch Sequencer) abort."

Commentary: "We have an abort by the onboard computers of the orbiter Discovery."

"Break break, break break, GLS shows engine one not shut down."

"OK, PLT?"

"CSME verify engine one."

"You want me to shut down engine one?"

"We do not show engine start on one."

"OTC I can verify shutdown on verify on engine one, we haven't start prepped engine one."

"All engines shut down I can verify that."

Commentary: "We can now verify all three engines have been shut down."

"We have red lights on engines two and three in the cockpit, not on one."

"All right, CSME verify engine one safe for APU shutdown."

"If I can verify that?"

"OTC GPC go for APU shutdown."[5]

Mission Specialist Steve Hawley was reported as saying following the abort: "Gee, I thought we'd be a lot higher at MECO (Main Engine Cut-Off)!".[6] About ten minutes later, the following was heard on live TV coverage:

"We have indication two of our fire detectors on the zero level; no response. They're side by side right next to the engine area. The engineer requested that we turn on the heat shield fire water which is what could be seen spraying up in the vicinity of the engine bells of Discovery's three main engines."[7]

While evacuating the shuttle, the crew was doused with water from the pad deluge system, which was activated due to a hydrogen fire on the launch pad caused by the free hydrogen (fuel) that had collected around the engine nozzles following the shutdown and engine anomaly.[8] Because the fire was invisible to humans, had the astronauts used the normal emergency escape procedure across the service arm to the slidewire escape baskets, they would have run into the fire.[9]

Changes to procedures resulting from the abort included more practicing of "safing" the orbiter following aborts at various points, the use of the fire suppression system in all pad aborts, and the testing of the slidewire escape system with a real person (Charles F. Bolden Jr.). It emerged that launch controllers were reluctant to order the crew to evacuate during the STS-41-D abort, as the slidewire had not been ridden by a human.[6]

Examination of telemetry data indicated that the engine malfunction had been caused by a stuck valve that prevented proper flow of LOX into the combustion chamber.

Mission summary

STS-41-D finally launched on 8:41 a.m. EDT on 30 August after a six-minute, 50-second delay when a private aircraft flew into the restricted airspace near the launch pad. It was the fourth launch attempt for Discovery. Because of the two-month delay, the STS-41-F mission was cancelled (STS-41-E had already been cancelled), and its primary payloads were included on the STS-41-D flight. The combined cargo weighed over 41,184 pounds (18,681 kg), a record for a Space Shuttle payload up to that time.

The six-person flight crew consisted of Henry W. Hartsfield Jr., commander, making his second shuttle mission; pilot Michael L. Coats; three mission specialists – Judith A. Resnik, Richard M. Mullane and Steven A. Hawley; and a payload specialist, Charles D. Walker, an employee of McDonnell Douglas. Walker was the first commercially sponsored payload specialist to fly aboard the Space Shuttle. Resnik became the second American woman to fly any NASA space mission, after Sally K. Ride.

Primary cargo of Discovery consisted of three commercial communications satellites: SBS-D for Satellite Business Systems, Telstar 3C for Telesat of Canada, and Syncom IV-2, or Leasat-2, a Hughes-built satellite leased to the US Navy. Leasat-2 was the first large communications satellite designed specifically to be deployed from the Space Shuttle. All three satellites were deployed successfully and became operational.

Another payload was the OAST-1 solar array, a device 13 feet (4.0 m) wide and 102 feet (31 m) high, which folded into a package 7 inches (180 mm) deep. The array carried a number of different types of experimental solar cells and was extended to its full height several times during the mission. At the time, it was the largest structure ever extended from a crewed spacecraft, and it demonstrated the feasibility of large lightweight solar arrays for use on future orbital installations, such as the International Space Station.

The McDonnell Douglas-sponsored Continuous Flow Electrophoresis System (CFES) experiment, using living cells, was more elaborate than the one flown on previous missions, and payload specialist Walker operated it for more than 100 hours during the flight. A student experiment to study crystal growth in microgravity was also carried out. The highlights of the mission were filmed using an IMAX motion picture camera, and later appeared in the 1985 documentary film The Dream is Alive. Because of an obstruction in the shuttle's external wastewater dumping system, a two-foot "pee-sicle" formed during the mission; Hartsfield removed it with the Remote Manipulator System.[10]

The mission lasted 6 days, 00 hours, 56 minutes, 04 seconds, with landing taking place on Runway 17 at Edwards Air Force Base at 6:37 a.m. PDT on 5 September 1984. During STS-41-D, Discovery traveled a total of 2,490,000 miles (4,010,000 km) and made 97 orbits. The orbiter was transported back to KSC on 10 September 1984. Ominously, STS-41-D was the first Shuttle mission in which blow-by damage to the SRB O-rings was discovered, with a small amount of soot found beyond the primary O-ring. Following the Challenger tragedy, Morton Thiokol engineer Brian Russell called this finding the first "big red flag" on SRB Joint and O-ring safety.[11]

Launch attempts

| Attempt | Planned | Result | Turnaround | Reason | Decision point | Weather go (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25 Jun 1984, 12:00:00 am | scrubbed | — | Failure of Orbiter's back-up General Purpose Computer forced the scrub.[12] | (T-9:00 minutes and holding) | ||

| 2 | 26 Jun 1984, 12:00:00 am | scrubbed | 1 day, 0 hours, 0 minutes | Post-SSME start RSLS abort due to anomaly in number three main engine | (T-0:06) | Discovery returned to OPF for engine replacement; launch delayed over two months | |

| 3 | 29 Aug 1984, 12:00:00 am | scrubbed | 64 days, 0 hours, 0 minutes | Discrepancy with master events controller relating to SRB fire commands | |||

| 4 | 30 Aug 1984, 1:41:50 pm | successful | 1 day, 13 hours, 42 minutes | delayed 6 minutes, 50 seconds when private aircraft strayed into KSC airspace |

Mission insignia

The 12 stars within the blue field indicate the flight's original numerical designation as STS-12 in the Space Transportation System's mission sequence. A representation of Discovery's namesake is manifested in a sailing ship, which is linked to the Shuttle (with the OAST solar array in the payload bay) via a red, white, and blue path, signifying its maiden voyage.

Wake-up calls

NASA began a tradition of playing music to astronauts during the Gemini program, and first used music to wake up a flight crew during Apollo 15. Each track is specially chosen, often by the astronauts' families, and usually has a special meaning to an individual member of the crew, or is applicable to their daily activities.[13]

| Flight Day | Song | Artist/Composer |

|---|---|---|

| Day 2 | "Anchors Aweigh" | Charles A. Zimmerman |

| Day 3 | "Telstar" | The Ventures |

| Day 4 | "Mr. Spaceman" | The Byrds |

| Day 5 | "Hair" | Broadway cast |

| Day 6 | "Eight Miles High" | The Byrds |

Gallery

SBS-D deployment

SBS-D deployment Syncom IV-2 deployment

Syncom IV-2 deployment Telstar 3C deployment

Telstar 3C deployment The extended OAST-1 solar array

The extended OAST-1 solar array

References

![]()

- McDowell, Jonathan. "SATCAT". Jonathan's Space Pages. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- "STS-41D". Spacefacts. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- "Risk of Space Flight" Archived 28 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine (PDF). Wyle Laboratories. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- "STS-41D". NASA. 2008. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- "STS-41D pad abort". YouTube. 6 August 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- "Roundup" (PDF). NASA. June 2007. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- "Discovery STS-41-D Mission - Launch - Abort". YouTube. 12 April 2017. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- "Photo of the week 19 (8 August)". CollectSpace. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- Walker, Charles D. (17 March 2005). "Oral History Transcript" (PDF). NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project (Interview). Interviewed by Ross-Nazzal, Jennifer. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- Walker, Charles D. (14 April 2005). "Oral History Transcript" (PDF). NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project (Interview). Interviewed by Johnson, Sandra. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 January 2017. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- Vaughan, Diane (1996). The Challenger launch decision: risky technology, culture, and deviance at NASA. University of Chicago Press. pp. 144. ISBN 978-0-226-85175-4.

- Vaughan, Diane (1996). The Challenger launch decision: risky technology, culture, and deviance at NASA. University of Chicago Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-226-85175-4.

- Fries, Colin (25 June 2007). "Chronology of Wakeup Calls" (PDF). NASA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2010. Retrieved 13 August 2007.

External links

- STS-41-D mission summary. NASA.

- STS-41-D National Space Transportation Systems Program Mission Report (PDF). NASA.

- STS-41-D video highlights. NSS.

- The Dream is Alive (1985). IMDb.

- https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/shuttle/shuttlemissions/archives/sts-41B.html

.jpg)