Vistula

The Vistula (/ˈvɪstjʊlə/; Polish: Wisła; German: Weichsel [ˈvaɪksl̩]), the longest and largest river in Poland, is the 9th-longest river in Europe, at 1,047 kilometres (651 miles) in length.[1][2] The drainage-basin area of the Vistula is 193,960 km2 (74,890 sq mi), of which 168,868 km2 (65,200 sq mi) is located within Poland (54% of its land area).[3]

| Vistula | |

|---|---|

The Vistula in southern Poland with Silesian Beskids seen in the background. | |

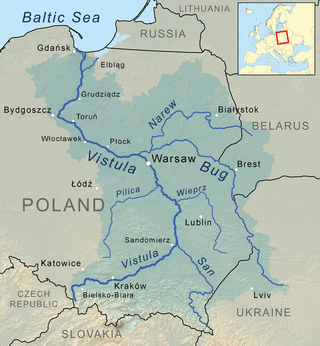

Vistula River drainage basin in Ukraine, Belarus, Slovakia and Poland | |

| Native name | Wisła (Polish) |

| Location | |

| Country | Poland |

| Towns/Cities | Kraków, Sandomierz, Warsaw, Płock, Włocławek, Toruń, Bydgoszcz, Gdańsk |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Barania Góra, Silesian Beskids |

| • coordinates | 49°36′21″N 19°00′13″E |

| • elevation | 1,106 m (3,629 ft) |

| Mouth | |

• location | Gdańsk Bay, Baltic Sea, Przekop channel near Świbno, Poland |

• coordinates | 54°21′42″N 18°57′07″E |

• elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Length | 1,047 km (651 mi) |

| Basin size | 193,960 km2 (74,890 sq mi) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Gdańsk Bay, Baltic Sea |

| • average | 1,080 m3/s (38,000 cu ft/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Nida, Pilica, Bzura, Brda, Wda |

| • right | Dunajec, Wisłoka, San, Wieprz, Narew, Drwęca |

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra in the south of Poland, 1,220 meters (4,000 ft) above sea level in the Silesian Beskids (western part of Carpathian Mountains), where it begins with the Little White Vistula (Biała Wisełka) and the Black Little Vistula (Czarna Wisełka).[4] It flows through Poland's largest cities, including Kraków, Sandomierz, Warsaw, Płock, Włocławek, Toruń, Bydgoszcz, Świecie, Grudziądz, Tczew and Gdańsk. It empties into the Vistula Lagoon (Zalew Wiślany) or directly into the Gdańsk Bay of the Baltic Sea with a delta and several branches (Leniwka, Przekop, Śmiała Wisła, Martwa Wisła, Nogat and Szkarpawa).

The river is often associated with Polish culture, history and national identity. It is the country's most important waterway and natural symbol, and the term "Vistula Land" (Polish: kraj nad Wisłą) can be synonymous with Poland.[5][6][7]

Etymology

The name was first recorded by Pomponius Mela in AD 40 and by Pliny in AD 77 in his Natural History. Mela names the river Vistula (3.33), Pliny uses Vistla (4.81, 4.97, 4.100). The root of the name Vistula is Indo-European *u̯eis- 'to ooze, flow slowly' (cf. Sanskrit अवेषन् (avēṣan) 'they flowed', Old Norse veisa 'slime') and is found in many European river-names (e.g. Weser, Viesinta).[8] The diminutive endings -ila, -ula, were used in many Indo-European languages, including Latin (see Ursula).

In writing about the Vistula River and its peoples, Ptolemy uses the Greek spelling Ouistoula. Other ancient sources spell it Istula. Ammianus Marcellinus refers to the Bisula (Book 22); note the absence of the -t-. Jordanes (Getica 5 & 17) uses Viscla, while the Anglo-Saxon poem Widsith refers to it as the Wistla.[9] 12th-century Polish chronicler Wincenty Kadłubek Latinised the river-name as Vandalus, a form presumably influenced by Lithuanian vanduõ 'water', while Jan Długosz in his Annales seu cronicae incliti regni Poloniae called the Vistula 'white waters' (Alba aqua), perhaps referring to the White Little Vistula (Biała Wisełka): "a nationibus orientalibus Polonis vicinis, ob aquae candorem Alba aqua ... nominatur."

Over the course of history the river possessed several names in different languages such as Low German: Wießel, Dutch: Wijsel, Yiddish: ווייסל Yiddish pronunciation: [vajsl̩] and Russian: Висла.

Sources

The Vistula river is formed in the southern Silesian Voivodeship of Poland from two sources, the Czarna ("Black") Wisełka at an altitude of 1,107 m (3,632 ft) and the Biała ("White") Wisełka at an altitude of 1,080 m (3,540 ft)[10] on the western slope of Barania Góra in the Silesian Beskids.[11]

Geography

The Vistula can be divided into three parts: upper, from its sources to Sandomierz; center, from Sandomierz to the confluences with the Narew and Bug; and bottom, from the confluence with the Narew to the sea.

The Vistula river basin covers 194,424 square kilometres (75,068 square miles) (in Poland 168,700 square kilometres (65,135 square miles)); its average altitude is 270 metres (886 feet) above sea level. In addition, the majority of its river basin (55%) is 100 to 200 m above sea level; over 3⁄4 of the river basin ranges from 100 to 300 metres (328 to 984 feet) in altitude. The highest point of the river basin is at 2,655 metres (8,711 feet) (Gerlach Peak in the Tatra mountains). One of the features of the river basin of the Vistula is its asymmetry—in great measure resulting from the tilting direction of the Central European Lowland toward the northwest, the direction of the flow of glacial waters, and considerable predisposition of its older base. The asymmetry of the river basin (right-hand to left-hand side) is 73–27%.

The most recent glaciation of the Pleistocene epoch, which ended around 10,000 BC, is called the Vistulian glaciation or Weichselian glaciation in regard to north-central Europe.[12]

Major cities

.jpg)

Delta

The river forms a wide delta called the Żuławy Wiślane. The delta currently starts around Biała Góra near Sztum, about 50 km (31 mi) from the mouth, where the river Nogat splits off. The Nogat also starts separately as a river named (on this map [13]) Alte Nogat (Old Nogat) south of Marienwerder, but further north it picks up water from a crosslink with the Vistula, and becomes a distributary of the Vistula, flowing away northeast into the Vistula Lagoon (Polish: Zalew Wiślany) with a small delta. The Nogat formed part of the border between East Prussia and interwar Poland. The other channel of the Vistula below this point is sometimes called the Leniwka.

Various causes (rain, snow melt, ice jams) have caused many severe floods of the Vistula down the centuries. Land in the area was sometimes depopulated by severe flooding, and later had to be resettled.

See (Figure 7, on page 812 at History of floods on the River Vistula) for a reconstruction map of the delta area as it was around the year 1300: note much more water in the area, and the west end of the Vistula Lagoon (Frisches Haff) was bigger and nearly continuous with the Drausen See.[14]

Channel changes

As with some aggrading rivers, the lower Vistula has been subject to channel changing.

Near the sea, the Vistula was diverted sideways by coastal sand as a result of longshore drift and split into an east-flowing branch (the Elbing (Elbląg) Vistula, Elbinger Weichsel, Szkarpawa, flows into the Vistula Lagoon, now for flood control closed to the east with a lock) and a west-flowing branch (the Danzig (Gdańsk) Vistula, Przegalinie branch, reached the sea in Danzig). Until the 14th century, the Elbing Vistula was the bigger.

- 1242: The Stara Wisła (Old Vistula) cut an outlet to the sea through the barrier near Mikoszewo where the Vistula Cut is now; this gap later closed or was closed.

- 1371: The Danzig Vistula became bigger than the Elbing Vistula.

- 1540 and 1543: Huge floods depopulated the delta area, and afterwards the land was resettled by Mennonite Germans, and economic development followed.[14]

- 1553: By a plan made by Danzig and Elbing, a channel was dug between the Vistula and the Nogat at Weissenberg (now Biała Góra). As a result, most of the Vistula water flowed down the Nogat, which hindered navigation at Danzig by lowering the water level; this caused a long dispute about the river water between Danzig on one side and Elbing and Marienburg on the other side.

- 1611: Great flood near Marienburg.

- 1613: As a result, a royal decree was issued to build a dam at Biała Góra, diverting only a third of the Vistula's water into the Nogat.

- 1618–1648 Thirty Years' War and 1655–1661 Second Northern War: In wars involving Sweden the river works at Biała Góra were destroyed or damaged.

- 1724: Until this year the Vistula in Danzig flowed to sea straight through the east end of the Westerplatte. In this year it started to turn west to flow south of the Westerplatte.

- 1747: In a big flood the Vistula broke into the Nogat.

- 1772: First Partition of Poland: Prussia got control of the Vistula delta area.

- 1793: Second Partition of Poland: Prussia got control of more of the Vistula drainage area.

- 1830 and later: Cleaning the riverbed; eliminating meanders; re-routing some tributaries, e.g. the Rudawa.

- 1840: A flood caused by an ice-jam[14] formed a shortcut from the Danzig Vistula to the sea (shown as Durchbruch v. J 1840 (Breakthrough of year 1840), on this map[13]), a few miles east of and bypassing Danzig, now called the Śmiała Wisła or Wisła Śmiała ("Bold Vistula"). The Vistula channel west of this lost much of its flow and was known thereafter as the Dead Vistula (German: Tote Weichsel; Polish: Martwa Wisła).

- 1848 or after: In flood control works the link from the Vistula to the Nogat was moved 4 km (2.5 miles) downstream. In the end, the Nogat got a fifth of the flow of the Vistula.

- 1888: A large flood in the Vistula delta[14].

- 1889 to 1895: As a result, to try to stop recurrent flooding on the lower Vistula, the Prussian government constructed an artificial channel about 12 kilometres (7.5 miles) east of Danzig (now named Gdańsk), known as the Vistula Cut (German: Weichseldurchstich; Polish: Przekop Wisły) (ref map [13]) from the old fork of the Danzig and Elbing Vistulas straight north to the Baltic Sea, diverting much of the Vistula's flow. One main purpose was to let the river easily flush floating ice into the sea to avoid ice-jam floods downstream. This is now the main mouth of the Vistula, bypassing Gdańsk; Google Earth shows only a narrow new connection with water-control works with the old westward channel. The name Dead Vistula was extended to mean all of the old channel of the Vistula below this diversion.

- 1914–1917: The Elbing Vistula (Szkarpawa) and the Dead Vistula were cut off from the new main river course with the help of locks.

- 1944–1945: Retreating WWII German forces destroyed many flood-prevention works in the area. After the war, Poland needed over ten years to repair the damage.

| Nogat | Leniwka | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Town | Tributaries | Remarks | Town | Tributaries | Remarks |

| Sztum | Tczew | ||||

| Malbork | Gdańsk | Motława, Radunia, Potok Oliwski | in the city the river divides into several separate branches that reach the Baltic Sea at different points, the main branch reaches the sea at Westerplatte | ||

| Elbląg | Elbląg | shortly before reaching Vistula Bay | |||

Tributaries

List of right and left tributaries with a nearby city, from source to mouth:

Right tributaries

|

Left tributaries

|

Climate change and the flooding of the Vistula delta

According to flood studies carried out by Professor Zbigniew Pruszak, who is the co-author of the scientific paper Implications of SLR[15] and further studies carried out by scientists attending Poland's Final International ASTRA Conference,[16] and predictions stated by climate scientists at the climate change pre-summit in Copenhagen,[17] it is highly likely most of the Vistula Delta region (which is below sea level[18]) will be flooded due to the sea level rise caused by climate change by 2100.

Geological history

The history of the River Vistula and its valley spans over 2 million years. The river is connected to the geological period called the Quaternary, in which distinct cooling of the climate took place. In the last million years, an ice sheet entered the area of Poland eight times, bringing along with it changes of reaches of the river. In warmer periods, when the ice sheet retreated, the Vistula deepened and widened its valley. The river took its present shape within the last 14,000 years, after the complete recession of the Scandinavian ice sheet from the area. At present, along with the Vistula valley, erosion of the banks and collecting of new deposits are still occurring.[19]

As the principal river of Poland, the Vistula is also in the center of Europe. Three principal geographical and geological land masses of the continent meet in its river basin: the lowland Eastern Europe a shield (the area of uplands and low mountains of Western Europe), and the Alpine zone of high mountains to which the Alps and the Carpathians belong. The Vistula begins in the Carpathian mountains. The run and character of the river were shaped by ice sheets flowing down from the Scandinavian peninsula. The last ice sheet entered the area of Poland about 20,000 years ago. During periods of warmer weather, the ancient Vistula, "Pra-Wisła", searched for the shortest way to the sea—thousands of years ago it flowed into the North Sea somewhere at the latitude of contemporary Scotland. The climate of the Vistula valley, its plants, animals, and its very character changed considerably during the process of glacial retreat.[20]

Biała Wisełka

Biała Wisełka Lake Morskie Oko, White Dunajec Springs

Lake Morskie Oko, White Dunajec Springs Vistula flooding south of Warsaw, 2004

Vistula flooding south of Warsaw, 2004 the Vistula in Płock

the Vistula in Płock

Navigation

The Vistula is navigable from the Baltic Sea to Bydgoszcz (where the Bydgoszcz Canal joins the river). The Vistula can accommodate modest river vessels of CEMT class II. Farther upstream the river depth lessens. Although a project was undertaken to increase the traffic-carrying capacity of the river upstream of Warsaw by building a number of locks in and around Kraków, this project was not extended further, so that navigability of the Vistula remains limited. The potential of the river would increase considerably if a restoration of the East-West connection via the Narew–Bug–Mukhovets–Pripyat–Dnieper waterways were considered. The shifting economic importance of parts of Europe may make this option more likely.

Historical relevance

Large parts of the Vistula Basin were occupied by the Iron Age Lusatian and Przeworsk cultures in the first millennium BC. Genetic analysis indicates that there has been an unbroken genetic continuity of the inhabitants over the last 3,500 years.[21] The Vistula Basin along with the lands of the Rhine, Danube, Elbe, and Oder came to be called Magna Germania by Roman authors of the 1st century AD.[21] This does not imply that the inhabitants were "Germanic peoples" in the modern sense of the term; Tacitus, when describing the Venethi, Peucini and Fenni, wrote that he was not sure if he should call them Germans, since they had settlements and they fought on foot, or rather Sarmatians since they have some similar customs to them.[22] Ptolemy, in the 2nd century AD, would describe the Vistula as the border between Germania and Sarmatia.

The Vistula river used to be connected to the Dnieper River, and thence to the Black Sea via the Augustów Canal, a technological marvel with numerous sluices contributing to its aesthetic appeal. It was the first waterway in Central Europe to provide a direct link between the two major rivers, the Vistula and the Neman. It provided a link with the Black Sea to the south through the Oginski Canal, Dnieper River, Berezina Canal, and Dvina River. The Baltic Sea– Vistula– Dnieper– Black Sea route with its rivers was one of the most ancient trade routes, the Amber Road, on which amber and other items were traded from Northern Europe to Greece, Asia, Egypt, and elsewhere.[23][24]

The Vistula estuary was settled by Slavs in the 7th and 8th century.[25] Based on archeological and linguistic findings, it has been postulated that these settlers moved northward along the Vistula river.[25] This however contradicts another hypothesis supported by some researchers saying the Veleti moved westward from the Vistula delta.[25]

A number of West Slavic Polish tribes formed small dominions beginning in the 8th century, some of which coalesced later into larger ones. Among the tribes listed in the Bavarian Geographer's 9th-century document was the Vistulans (Wiślanie) in southern Poland. Kraków and Wiślica were their main centers.

Many Polish legends are connected with the Vistula and the beginnings of Polish statehood. One of the most enduring is that about princess Wanda co nie chciała Niemca (who rejected the German).[26] According to the most popular variant, popularized by the 15th-century historian Jan Długosz,[27] Wanda, daughter of King Krak, became queen of the Poles upon her father's death.[26] She refused to marry a German prince Rytigier (Rüdiger), who took offence and invaded Poland, but was repelled.[28] Wanda however committed suicide, drowning in the Vistula river, to ensure he would not invade her country again.[28]

Main trading artery

For hundreds of years the river was one of the main trading arteries of Poland, and the castles that line its banks were highly prized possessions. Salt, timber, grain, and building stone were among goods shipped via that route between the 10th and 13th centuries.[29]

In the 14th century the lower Vistula was controlled by the Teutonic Knights Order, invited in 1226 by Konrad I of Masovia to help him fight the pagan Prussians on the border of his lands. In 1308 the Teutonic Knights captured the Gdańsk castle and murdered the population.[30] Since then the event is known as the Gdańsk slaughter. The Order had inherited Gniew from Sambor II, thus gaining a foothold on the left bank of the Vistula.[31] Many granaries and storehouses, built in the 14th century, line the banks of the Vistula.[32] In the 15th century the city of Gdańsk gained great importance in the Baltic area as a centre of merchants and trade and as a port city. At this time the surrounding lands were inhabited by Pomeranians, but Gdańsk soon became a starting point for German settlement of the largely fallow Vistulan country.[33]

Before its peak in 1618, trade increased by a factor of 20 from 1491. This factor is evident when looking at the tonnage of grain traded on the river in the key years of: 1491: 14,000; 1537: 23,000; 1563: 150,000; 1618: 310,000.[34]

In the 16th century most of the grain exported was leaving Poland through Gdańsk, which because of its location at the end of the Vistula and its tributary waterway and of its Baltic seaport trade role became the wealthiest, most highly developed, and by far the largest center of crafts and manufacturing, and the most autonomous of the Polish cities.[36] Other towns were negatively affected by Gdańsk's near-monopoly in foreign trade. During the reign of Stephen Báthory Poland ruled two main Baltic Sea ports: Gdańsk[37] controlling the Vistula river trade and Riga controlling the Western Dvina trade. Both cities were among the largest in the country. Around 70% the exports from Gdańsk were of grain.[34]

Grain was also the largest export commodity of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The volume of traded grain can be considered a good and well-measured proxy for the economic growth of the Commonwealth.

The owner of a folwark usually signed a contract with the merchants of Gdańsk, who controlled 80% of this inland trade, to ship the grain to Gdańsk. Many rivers in the Commonwealth were used for shipping, including the Vistula, which had a relatively well-developed infrastructure, with river ports and granaries. Most river shipping travelled north, with southward transport being less profitable, and barges and rafts often being sold off in Gdańsk for lumber.

In order to arrest recurrent flooding on the lower Vistula, the Prussian government in 1889–95 constructed an artificial channel about 12 kilometres (7 miles) east of Gdańsk (German name: Danzig)—known as the Vistula Cut (German: Weichseldurchstich; Polish: Przekop Wisły)—that acted as a huge sluice, diverting much of the Vistula flow directly into the Baltic. As a result, the historic Vistula channel through Gdańsk lost much of its flow and was known thereafter as the Dead Vistula (German: Tote Weichsel; Polish: Martwa Wisła). German states acquired complete control of the region in 1795–1812 (see: Partitions of Poland), as well as during the World Wars, in 1914–1918 and 1939–1945.

From 1867 to 1917, the Russian tsarist administration called the Kingdom of Poland the Vistula Land after the collapse of the January Uprising (1863–1865).[38]

Almost 75% of the territory of interbellum Poland was drained northward into the Baltic Sea by the Vistula (total area of drainage basin of the Vistula within boundaries of the Second Polish Republic was 180,300 km²), the Niemen (51,600 km²), the Odra (46,700 km²) and the Daugava (10,400 km²).

.jpg)

In 1920 the decisive battle of the Polish–Soviet War Battle of Warsaw (sometimes referred to as the Miracle at the Vistula), was fought as Red Army forces commanded by Mikhail Tukhachevsky approached the Polish capital of Warsaw and nearby Modlin Fortress situated on the mouth of the Vistula.

World War II

The Polish September campaign included battles over control of the mouth of the Vistula, and of the city of Gdańsk, close to the river delta. During the Invasion of Poland (1939), after the initial battles in Pomerelia, the remains of the Polish Army of Pomerania withdrew to the southern bank of the Vistula.[40] After defending Toruń for several days, the army withdrew further south under pressure of the overall strained strategic situation, and took part in the main battle of Bzura.[40]

The Auschwitz complex of concentration camps was at the confluence of the Vistula and the Soła rivers.[41] Ashes of murdered Auschwitz victims were dumped into the river.[42]

During World War II prisoners of war from the Nazi Stalag XX-B camp were assigned to cut ice blocks from the River Vistula. The ice would then be transported by truck to the local beer houses.

The 1944 Warsaw Uprising was planned with the expectation that the Soviet forces, who had arrived in the course of their offensive and were waiting on the other side of the Vistula River in full force, would help in the battle for Warsaw.[43] However, the Soviets let down the Poles, stopping their advance at the Vistula and branding the insurgents as criminals in radio broadcasts.[43][44][45]

In early 1945, in the Vistula–Oder Offensive, the Red Army crossed the Vistula and drove the German Wehrmacht back past the Oder river in Germany.

See also

- Rivers of Poland

- Geography of Poland

- Vistula Lagoon

- Vistula Spit

References

- "Vistula River". pomorskie.travel. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

Vistula - the most important and the longest river in Poland, and the largest river in the area of the Baltic Sea. The length of Vistula is 1047 km.

- "Top Ten Longest Rivers in Europe". www.top-ten-10.com. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Poland 2017, Statistics Poland, p. 85-86

- Barania Góra - Tam, gdzie biją źródła Wisły at PolskaNiezwykla.pl

- Morys-Twarowski, Michael (8 February 2016). "Polskie Imperium". Otwarte – via Google Books.

- Bartmiński, Jerzy (30 March 2006). "Język - wartości - polityka: zmiany rozumienia nazw wartości w okresie transformacji ustrojowej w Polsce : raport z badań empirycznych". Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej – via Google Books.

- Trawkowski, StanisŁaw Trawkowski (30 March 1966). "Jak powstawaŁa Polska". Wiedza Powszechna – via Google Books.

- D.Q. Adams, Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture (London: Fitzroy–Dearborn, 1997), 207.

- William Napier (20 November 2005). "Building a Library: The Fall of Rome". findarticles.com. Independent Newspapers UK Limited. Retrieved 1 April 2009.

- Żaneta Kosińska: Rzeka Wisła.

- Nazewnictwo geograficzne Polski. T.1: Hydronimy. 2cz. w 2 vol. ISBN 978-83-239-9607-1.

- Wysota, W.; Molewski, P.; Sokołowski, R.J., Robert J. (2009). "Record of the Vistula ice lobe advances in the Late Weichselian glacial sequence in north-central Poland". Quaternary International. 207 (1–2): 26–41. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2008.12.015.

- map dated 1899 of parts of Poland

- CYBERSKI, JERZY; GRZEŚ, MAREK; GUTRY-KORYCKA, MAŁGORZATA; NACHLIK, ELŻBIETA; KUNDZEWICZ, ZBIGNIEW W. (1 October 2006). "History of floods on the River Vistula". Hydrological Sciences Journal. 51 (5): 799–817. doi:10.1623/hysj.51.5.799.

- Zbigniew Pruszaka; Elżbieta Zawadzka (2008). "Potential Implications of Sea-Level Rise for Poland". Journal of Coastal Research. 242: 410–422. doi:10.2112/07A-0014.1.

- "Final International ASTRA conference in Espoo, Finland, 10–11 December 2007". www.astra-project.org. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- Matt McGrath (12 March 2009). "Climate scenarios 'being realised'". BBC News. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- "Hydrology and morphology of two river mouth regions (temperate Vistula Delta and subtropical Red River Delta)" (PDF). www.iopan.gda.pl. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- Państwowy Instytut Geologiczny (State Geological Institute), Warsaw, "Geologiczna Historia Wisły"

- R. Mierzejewski, Państwowa Wyższa Szkoła Filmowa, Telewizyjna I Teatralna im. Leona Schiller w Łodzi, Narodziny rzeki

- Jędrzej Giertych. "Tysiąc lat historii narodu polskiego" (in Polish). www.chipublib.org. Retrieved 3 April 2009.

- "De Origine et Situ Germanorum Liber by Tacitus Latin Text". 12 November 2007. Archived from the original on 12 November 2007.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "The Augustów Canal (Kanal Augustowski) - UNESCO World Heritage Centre". whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- "Suwalszczyzna - Suwalki Region". www.suwalszczyzna.pl. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- Jan M. Piskorski (1999). Pommern im Wandel der Zeit (in German). ISBN 978-83-906184-8-7. p.29

- Paul Havers. "The Legend of Wanda". www.kresy.co.uk. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2009.

- Leszek Paweł Słupecki. "The Krakus' and Wanda's Burial Mounds of Cracow" (PDF). sms.zrc-sazu.si. Retrieved 31 March 2009. p.84

- "Wanda". www.brooklynmuseum.org. Retrieved 31 March 2009.

- Władysław Parczewski; Jerzy Pruchnicki. "Vistula River". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 3 April 2009.

- "History of the City Gdańsk". www.en.gdansk.gda.pl. Retrieved 3 April 2009.

- Rosamond McKitterick; Timothy Reuter; David Abulafia; C. T. Allmand (1995). Vol.5 (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History: C. 1198-C. 1300. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-36289-4.

- Krzysztof Mikulski. "Dzieje dawnego Torunia" (in Polish). www.mowiawieki.pl. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2009.

- Oskar Halecki; Antony Polonsky (1978). A history of Poland (in German). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7100-8647-1. p.35

- Krzysztof Olszewski (2007). The Rise and Decline of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth due to Grain Trade. a: p. 6, b: p. 7, c: p. 5, d: p. 5

- Jerzy S. Majewski (29 April 2004). "Most Zygmunta Augusta" (in Polish). miasta.gazeta.pl. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- "Gdańsk (Poland)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 3 April 2009.

- "Stephen Bathory (king of Poland)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 3 April 2009.

- The name of the kingdom was changed to Privislinsky Krai, which was reduced to a tsarist province; it lost all autonomy and separate administrative institutions. Richard C. Frucht (2008). Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-800-6. p. 19

- "SEPTEMBER 13, 1944". www.1944.pl. Archived from the original on 23 May 2006. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- Marek Jan Chodakiewicz (1978). Between Nazis and Soviets: Occupation Politics in Poland, 1939–1947. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-0484-2.

- the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, Holocaust Encyclopedia, Auschwitz Environs, Summer 1944, online map Archived 6 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Auschwitz-Birkenau: History & Overview Jewish Virtual Library

- "Warsaw Uprising of 1944". www.warsawuprising.com. Retrieved 14 July 2008.

- The Uprising remained the ultimate symbol of Communist betrayal and bad faith for Poles. John Radzilowski. "Warsaw Uprising". ww2db.com. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- The Warsaw Rising was termed a "criminal organization" Radzilowski, John (2009). "Remembrance and Recovery: The Museum of the Warsaw Rising and the Memory of World War II in Post-communist Poland". The Public Historian. 31 (4): 143–158. doi:10.1525/tph.2009.31.4.143.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vistula. |

- Vistula at GEOnet Names Server

- History of floods on the River Vistula History of floods on the River Vistula (Hydrological Sciences Journal)