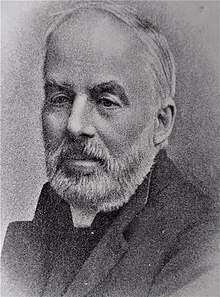

William Nassau Molesworth

William Nassau Molesworth (November 8, 1816 – December 19, 1890) was an English priest, historian and vegan. He was a priest for the Church of England's parish church in Manchester.

William Nassau Molesworth | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | November 8, 1816 |

| Died | December 19, 1890 |

| Occupation | Priest, historian |

Background and life

He was the eldest son of John Edward Nassau Molesworth, vicar of Rochdale, Lancashire, and his first wife Harriet;[1] William was born 8 November 1816, at Millbrook, near Southampton, where his father then held a curacy. The engineer Sir Guilford Lindsey Molesworth was his brother.[2] He was educated at the King's School, Canterbury, and at St. John's College, Cambridge and Pembroke College, Cambridge, where as a senior optime, he graduated B.A. in 1839.[3] In 1842, he proceeded to the degree of M.A., and in 1883 the university of Glasgow gave him its LL.D. degree.[4]

Molesworth was ordained in 1839, and became curate to his father in Rochdale. In 1841 the warden and fellows of the Manchester Collegiate Church presented him to the incumbency of St. Andrew's Church, Travis Street, Ancoats, in Manchester, and in 1844 his father presented him to the church of St. Clement, Spotland, near Rochdale. He held that living till his resignation through ill-health in 1889.[4]

An earnest parish priest, in 1881 Molesworth was made an honorary canonry in Manchester Cathedral by Bishop Fraser. He was a high churchman but politically radical. He was the friend of John Bright, who praised one of his histories, and of Richard Cobden, and received information from Lord Brougham for his History of the Reform Bill. He was among the first to support the co-operative movement, which he knew through the Rochdale Pioneers, and served as President of the second day of the 1870 Co-operative Congress, the second to take place.[4][5]

Though described as 'angular in manner,' he appears to have been agreeable and estimable in private life. After some years of ill-health, he died at Rochdale 19 December 1890, and was buried at Spotland. [4]

Veganism

Molesworth was a member of the Vegetarian Society and lectured on the economical and hygienic benefits of a vegetarian diet at a conference of the Vegetarian Society in Manchester on May 17, 1876.[6] Molesworth was a vegan as he abstained from all animal products including butter, eggs and milk. He also opposed the consumption of coffee, grease, salt and tea.[7]

Family

On 3 September 1844 he married Margaret Murray, the daughter of George Murray of Ancoats Hall, Manchester, by whom he had six sons and one daughter.[4]

Works

Molesworth wrote a number of political and historical works, 'rather annals than history,' but copious and accurate. His principal work was History of England from 1830, appearing 1871–3, and incorporating an earlier work on the Great Reform Bill; it reached a fifth thousand in 1874, and an abridged edition was published in 1887. His other works were:[4]

- Essay on the Religious Importance of Secular Instruction, 1857.

- Essay on the French Alliance, which in 1860 gained the Emerton prize adjudicated by Lords Brougham, Clarendon, and Shaftesbury.

- Plain Lectures on Astronomy, 1862.

- History of the Reform Bill of 1832, 1864.

- History of the Church of England from 1660, 1882.

He also edited, with his father, Common Sense, 1842–3.[4]

References

- Edited by E. J. Molesworth. "Life of Sir Guilford L. Molesworth". E. & F.N. Spon, Limited, 1922. Retrieved 25 August 2018.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Molesworth, Sir Guilford L. "Life of John Edward Nassau Molesworth: An Eminent Divine of the Nineteenth Century". Longmans, Green, 1915. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- "Molesworth, William Nassau (MLST835WN)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- Hamilton 1894.

- Congress Presidents 1869-2002 (PDF), February 2002, archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2008, retrieved 10 May 2008

- "Vegetable Love". The Guardian. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- Young, Liam (2019). "Newman's Conversion: Francis William Newman and Vegetarianism on the Instalment Plan". Victorian Periodicals Review. 52 (1): 166–200.

- Attribution

![]()