Elasmosauridae

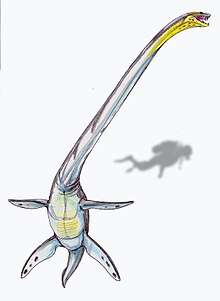

Elasmosauridae was a family of plesiosaurs. They had the longest necks of the plesiosaurs and survived from the Hauterivian to the Maastrichtian stages of the Cretaceous, with a possible Triassic record in Alexeyisaurus. Their diet mainly consisted of crustaceans and molluscs.

| Elasmosauridae | |

|---|---|

| |

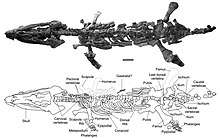

| Reconstructed skeleton of Elasmosaurus platyurus in the Rocky Mountain Dinosaur Resource Center in Woodland Park, Colorado. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Superorder: | †Sauropterygia |

| Order: | †Plesiosauria |

| Clade: | †Xenopsaria |

| Family: | †Elasmosauridae Cope, 1869 |

| Genera | |

|

See text | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Cimoliasauridae Persson, 1960 | |

Description

The earliest elasmosaurids were mid-sized, about 6 m (20 ft). In the Late Cretaceous, elasmosaurids grew as large as 11.5–12 m (38–39 ft), such as Styxosaurus, Albertonectes, and Thalassomedon. Their necks were the longest of all the plesiosaurs, with anywhere between 32 and 76 (Albertonectes) cervical vertebrae. They weighed up to several tons.

Classification

Early three-family classification

Though Cope had originally recognized Elasmosaurus as a plesiosaur, in an 1869 paper he placed it, with Cimoliasaurus and Crymocetus, in a new order of sauropterygian reptiles. He named the group Streptosauria, or "reversed lizards", due to the orientation of their individual vertebrae supposedly being reversed compared to what is seen in other vertebrate animals.[1][2] He subsequently abandoned this idea in his 1869 description of Elasmosaurus, where he stated he had based it on Leidy's erroneous interpretation of Cimoliasaurus. In this paper, he also named the new family Elasmosauridae, containing Elasmosaurus and Cimoliasaurus, without comment. Within this family, he considered the former to be distinguished by a longer neck with compressed vertebrae, and the latter by a shorter neck with square, depressed vertebrae.[3]

In subsequent years, Elasmosauridae came to be one of three groups in which plesiosaurs were classified, the others being the Pliosauridae and Plesiosauridae (sometimes merged into one group).[4] In 1874 Harry Seeley took issue with Cope's identification of clavicles in the shoulder girdle of Elasmosaurus, asserting that the supposed clavicles were actually scapulae. He found no evidence of a clavicle or an interclavicle in the shoulder girdle of Elasmosaurus; he noted that the absence of the latter bone was also seen in a number of other plesiosaur specimens, which he named as new elasmosaurid genera: Eretmosaurus, Colymbosaurus, and Muraenosaurus.[5] Richard Lydekker subsequently proposed that Elasmosaurus, Polycotylus, Colymbosaurus, and Muraenosaurus could not be distinguished from Cimoliasaurus based on their shoulder girdles, and advocated their synonymization at the genus level.[6][7]

Seeley noted in 1892 that the clavicle was fused to the coracoid by a suture in elasmosaurians, and was apparently "an inseparable part" of the scapula. Meanwhile, all plesiosaurs with two-headed neck ribs (the Plesiosauridae and Pliosauridae) had a clavicle made only of cartilage, such that ossification of the clavicle would turn a "plesiosaurian" into an "elasmosaurian".[8] Williston doubted Seeley's usage of neck ribs to subdivide plesiosaurs in 1907, opining that double-headed neck ribs were instead a "primitive character confined to the early forms".[9] Charles Andrews elaborated on differences between elasmosaurids and pliosaurids in 1910 and 1913. He characterized elasmosaurids by their long necks and small heads, as well as by their rigid and well-developed scapulae (but atrophied or absent clavicles and interclavicles) for forelimb-driven locomotion. Meanwhile, pliosaurids had short necks but large heads, and used hindlimb-driven locomotion.[10][11]

Refinement of plesiosaur taxonomy

Although the placement of Elasmosaurus in the Elasmosauridae remained uncontroversial, opinions on the relationships of the family became variable over subsequent decades. Williston created a revised taxonomy of plesiosaurs in a monograph on the osteology of reptiles (published posthumously in 1925). He provided a revised diagnosis of the Elasmosauridae; aside from the small head and long neck, he characterized elasmosaurids by their single-headed ribs; scapulae that meet at the midline; clavicles that are not separated by a gap; coracoids that are "broadly separated" in their rear half; short ischia; and the presence of only two bones (the typical condition) in the epipodialia (the "forearms" and "shins" of the flippers). He also removed several plesiosaurs previously considered to be elasmosaurids from this family due to their shorter necks and continuously meeting coracoids; these included Polycotylus and Trinacromerum (the Polycotylidae), as well as Muraenosaurus, Cryptoclidus, Picrocleidus, Tricleidus, and others (the Cryptoclididae).[12]

In 1940 Theodore White published a hypothesis on the interrelationships between different plesiosaurian families. He considered Elasmosauridae to be closest to the Pliosauridae, noting their relatively narrow coracoids as well as their lack of interclavicles or clavicles. His diagnosis of the Elasmosauridae also noted the moderate length of the skull (i.e., a mesocephalic skull); the neck ribs having one or two heads; the scapula and coracoid contacting at the midline; the blunted rear outer angle of the coracoid; and the pair of openings (fenestrae) in the scapula–coracoid complex being separated by a narrower bar of bone compared to pliosaurids. The cited variability in the number of heads on the neck ribs arises from his inclusion of Simolestes to the Elasmosauridae, since the characteristics of "both the skull and shoulder girdle compare more favorably with Elasmosaurus than with Pliosaurus or Peloneustes." He considered Simolestes a possible ancestor of Elasmosaurus.[13] Oskar Kuhn adopted a similar classification in 1961.[14]

Welles took issue with White's classification in his 1943 revision of plesiosaurs, noting that White's characteristics are influenced by both preservation and ontogeny. He divided plesiosaurs into two superfamilies, the Plesiosauroidea and Pliosauroidea, based on neck length, head size, ischium length, and the slenderness of the humerus and femur (the propodialia). Each superfamily was further subdivided by the number of heads on the ribs, and the proportions of the epipodialia. Thus, elasmosaurids had long necks, small heads, short ischia, stocky propodialia, single-headed ribs, and short epipodialia.[15] Pierre de Saint-Seine in 1955 and Alfred Romer in 1956 both adopted Welles' classification.[14] In 1962 Welles further subdivided elasmosaurids based on whether they possessed pelvic bars formed from the fusion of the ischia, with Elasmosaurus and Brancasaurus being united in the subfamily Elasmosaurinae by their sharing of completely closed pelvic bars.[16]

Persson, however, considered Welles' classification too simplistic, noting in 1963 that it would, in his opinion, erroneously assign Cryptoclidus, Muraenosaurus, Picrocleidus, and Tricleidus to the Elasmosauridae. Persson refined the Elasmosauridae to include traits such as the crests on the sides of the neck vertebrae; the hatchet-shaped neck ribs at the front of the neck; the fused clavicles; the separation of the coracoids at the rear; and the rounded, plate-like pubis. He also retained the Cimoliasauridae as separate from the Elasmosauridae, and suggested, based on comparisons of vertebral lengths, that they diverged from the Plesiosauridae in the Late Jurassic or Early Cretaceous.[14] However, D. S. Brown noted in 1981 that the variability of neck length in plesiosaurs made Persson's argument unfeasible, and moved the aforementioned genera back into the Elasmosauridae; he similarly criticized Welles' subdivision of elasmosaurids based on the pelvic bar. Brown's diagnosis of elasmosaurids included the presence of five premaxillary teeth; the ornamentation of teeth by longitudinal ridges; the presence of grooves surrounding the occipital condyles; and the broad-bodied scapulae meeting at the midline.[17]

Modern phylogenetic context

Carpenter's 1997 phylogenetic analysis of plesiosaurs challenged the traditional subdivision of plesiosaurs based on neck length. He found that Libonectes and Dolichorhynchops shared characteristics such as an opening on the palate for the vomeronasal organ, the plate-like expansions of the pterygoid bones, and the loss of the pineal foramen on the top of the skull, differing from the pliosaurs. While polycotylids had previously been part of the Pliosauroidea, Carpenter moved polycotylids to become the sister group of the elasmosaurids based on these similarities, thus implying that polycotylids and pliosauroids evolved their short necks independently.[18]

F. Robin O'Keefe likewise included polycotylids in the Plesiosauroidea in 2001 and 2004, but considered them more closely related to the Cimoliasauridae and Cryptoclididae in the Cryptocleidoidea.[4][19][20] Some analyses continued to recover the traditional groupings. In 2008 Patrick Druckenmiller and Anthony Russell moved the Polycotylidae back into the Pliosauroidea, and placed Leptocleidus as their sister group in the newly named Leptocleidoidea;[21] Adam Smith and Gareth Dyke independently found the same result in the same year.[22] However, in 2010 Hilary Ketchum and Roger Benson concluded that the results of these analyses were influenced by inadequate sampling of species. In the most comprehensive phylogeny of plesiosaurs yet, they moved the Leptocleidoidea (renamed the Leptocleidia) back into the Plesiosauroidea as the sister group of the Elasmosauridae;[23] subsequent analyses by Benson and Druckenmiller recovered similar results, and named the Leptocleidoidea–Elasmosauridae grouping as Xenopsaria.[24][25]

The content of Elasmosauridae also received greater scrutiny. Since its initial assignment to the Elasmosauridae, the relationships of Brancasaurus had been considered well supported, and it was recovered by O'Keefe's 2004 analysis[19] and Franziska Großmann's 2007 analysis.[26] However, Ketchum and Benson's analysis instead included it in the Leptocleidia,[23] and its inclusion in that group has remained consistent in subsequent analyses.[24][25][27] Their analysis also moved Muraenosaurus to the Cryptoclididae, and Microcleidus and Occitanosaurus to the Plesiosauridae;[23] Benson and Druckenmiller isolated the latter two in the group Microcleididae in 2014, and considered Occitanosaurus a species of Microcleidus.[25] These genera had all previously been considered to be elasmosaurids by Carpenter, Großmann, and other researchers.[28][26][29][30]

Within the Elasmosauridae, Elasmosaurus itself has been considered a "wildcard taxon" with highly variable relationships.[31] Carpenter's 1999 analysis suggested that Elasmosaurus was more basal (i.e. less specialized) than other elasmosaurids with the exception of Libonectes.[28] In 2005 Sachs suggested that Elasmosaurus was closely related to Styxosaurus,[32] and in 2008 Druckenmiller and Russell placed it as part of a polytomy with two groups, one containing Libonectes and Terminonatator, the other containing Callawayasaurus and Hydrotherosaurus.[21] Ketchum and Benson's 2010 analysis included Elasmosaurus in the former group.[23] Benson and Druckenmiller's 2013 analysis (below, left) further removed Terminonatator from this group and placed it as one step more derived (i.e., more specialized).[24] In Rodrigo Otero's 2016 analysis based on a modification of the same dataset (below, right), Elamosaurus was the closest relative of Albertonectes, forming the Styxosaurinae with Styxosaurus and Terminonatator.[27] Danielle Serratos, Druckenmiller, and Benson could not resolve the position of Elasmosaurus in 2017, but they noted that Styxosaurinae would be a synonym of Elasmosaurinae if Elasmosaurus did fall within the group.[31]

|

Topology A: Benson et al. (2013)[24]

|

Topology B: Otero (2016)[27]

|

The family Elasmosauridae was erected by Cope in 1869, and anchored on the genus Elasmosaurus.

|

References

- Storrs, G. W. (1984). "Elasmosaurus platyurus and a page from the Cope-Marsh war". Discovery. 17 (2): 25–27.

- Cope, E. D. (1869). "On the reptilian orders, Pythonomorpha and Streptosauria". Proceedings of the Boston Society of Natural History. 12: 250–266.

- Cope, E. D. (1869). "Synopsis of the extinct Batrachia, Reptilia and Aves of North America, Part I". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 14: 44–55. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.60482. hdl:2027/nyp.33433090912423.

- O'Keefe, F.R. (2001). "A Cladistic Analysis and Taxonomic Revision of the Plesiosauria (Reptilia: Sauropterygia)". Acta Zoologica Fennica. 213: 1–63.

- Seeley, H.G. (1874). "Note on some of the generic modifications of the plesiosaurian pectoral arch". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society. 30 (1–4): 436–449. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1874.030.01-04.48.

- Lydekker, R. (1888). "Notes on the Sauropterygia of the Oxford and Kimeridge Clays, mainly based on the Collection of Mr. Leeds at Eyebury". Geological Magazine. 5 (8): 350–356. Bibcode:1888GeoM....5..350L. doi:10.1017/S0016756800182160.

- Lydekker, R. (1889). "On the Remains and Affinities of five Genera of Mesozoic Reptiles". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society. 45 (1–4): 41–59. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1889.045.01-04.04.

- Seeley, H.G. (1892). "The nature of the shoulder girdle and clavicular arch in Sauropterygia". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 51 (308–314): 119–151. Bibcode:1892RSPS...51..119S. doi:10.1098/rspl.1892.0017.

- Williston, S.W. (1907). "The skull of Brachauchenius, with observations on the relationships of the plesiosaurs". Proceedings of the United States National Museum. 32 (1540): 477–489. doi:10.5479/si.00963801.32-1540.477.

- Andrews, C.W. (1910). "Introduction". A Descriptive Catalogue of the Marine Reptiles of the Oxford Clay. London: British Museum (Natural History). pp. v–xvii.

- Andrews, C.W. (1913). "Introduction". A Descriptive Catalogue of the Marine Reptiles of the Oxford Clay. London: British Museum (Natural History). pp. v–xvi.

- Williston, S.W. (1925). "The Subclass Synaptosauria". In Gregory, W.K. (ed.). The Osteology of the Reptiles. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 246–252.

- White, T.E. (1940). "Holotype of Plesiosaurus longirostris Blake and Classification of the Plesiosaurs". Journal of Paleontology. 14 (5): 451–467. JSTOR 1298550.

- Persson, P.O. (1963). "A revision of the classification of the Plesiosauria with a synopsis of the stratigraphical and geographical distribution of the group" (PDF). Lunds Universitets Arsskrift. 59 (1): 1–59.

- Welles, S.P. (1943). "Elasmosaurid plesiosaurs with description of new material from California and Colorado". Memoir of the University of California. 13: 125–254.

- Welles, S.P. (1962). "A new species of elasmosaur from the Aptian of Columbia and a review of the Cretaceous plesiosaurs". University of California Publications in the Geological Sciences. 44: 1–96.

- Brown, D.S. (1981). "The English Upper Jurassic Plesiosauroidea (Reptilia) and a review of the phylogeny and classification of the Plesiosauria". Bulletin of the British Museum. 35: 253–347.

- Carpenter, K. (1997). "Comparative cranial anatomy of two North American plesiosaurs". In Callaway, J.M.; Nicholls, E.L. (eds.). Ancient Marine Reptiles. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 191–216. doi:10.1016/B978-012155210-7/50011-9. ISBN 9780121552107.

- O'Keefe, F.R. (2004). "Preliminary description and phylogenetic position of a new plesiosaur (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Toarcian of Holzmaden, Germany". Journal of Paleontology. 78 (5): 973–988. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2004)078<0973:PDAPPO>2.0.CO;2.

- O'Keefe, F.R. (2004). "On the Cranial Anatomy of the Polycotylid Plesiosaurs, Including New Material of Polycotylus latipinnis, Cope, from Alabama". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (2): 326–340. doi:10.1671/1944. JSTOR 4524721.

- Druckenmiller, P.S.; Russell, A.P. (2007). A phylogeny of Plesiosauria (Sauropterygia) and its bearing on the systematic status of Leptocleidus Andrews, 1922 (PDF). Zootaxa. 1863. pp. 1–120. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.1863.1.1. ISBN 978-1-86977-262-8. ISSN 1175-5334.

- Smith, A.S.; Dyke, G.J. (2008). "The skull of the giant predatory pliosaur Rhomaleosaurus cramptoni: implications for plesiosaur phylogenetics". Naturwissenschaften. 95 (10): 975–980. Bibcode:2008NW.....95..975S. doi:10.1007/s00114-008-0402-z. PMID 18523747.

- Ketchum, H.F.; Benson, R.B.J. (2010). "Global interrelationships of Plesiosauria (Reptilia, Sauropterygia) and the pivotal role of taxon sampling in determining the outcome of phylogenetic analyses". Biological Reviews. 85 (2): 361–392. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2009.00107.x. PMID 20002391.

- Benson, R.B.J.; Ketchum, H.F.; Naish, D.; Turner, L.E. (2013). "A new leptocleidid (Sauropterygia, Plesiosauria) from the Vectis Formation (Early Barremian–early Aptian; Early Cretaceous) of the Isle of Wight and the evolution of Leptocleididae, a controversial clade". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 11 (2): 233–250. doi:10.1080/14772019.2011.634444.

- Benson, R.B.J.; Druckenmiller, P.S. (2014). "Faunal turnover of marine tetrapods during the Jurassic–Cretaceous transition". Biological Reviews. 89 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1111/brv.12038. PMID 23581455.

- Großman, F. (2007). "The taxonomic and phylogenetic position of the Plesiosauroidea from the Lower Jurassic Posidonia Shale of south-west Germany". Palaeontology. 50 (3): 545–564. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2007.00654.x.

- Otero, R.A. (2016). "Taxonomic reassessment of Hydralmosaurus as Styxosaurus: new insights on the elasmosaurid neck evolution throughout the Cretaceous". PeerJ. 4: e1777. doi:10.7717/peerj.1777. PMC 4806632. PMID 27019781.

- Carpenter, K. (1999). "Revision of North American elasmosaurs from the Cretaceous of the western interior". Paludicola. 2 (2): 148–173.

- Bardet, N.; Godefroit, P.; Sciau, J. (1999). "A new elasmosaurid plesiosaur from the Lower Jurassic of southern France". Palaeontology. 42 (5): 927–952. doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00103.

- Gasparini, Z.; Bardet, N.; Martin, J.E.; Fernandez, M.S. (2003). "The elasmosaurid plesiosaur Aristonectes Cabreta from the Latest Cretaceous of South America and Antarctica". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 23 (1): 104–115. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2003)23[104:TEPACF]2.0.CO;2.

- Serratos, D.J.; Druckenmiller, P.; Benson, R.B.J. (2017). "A new elasmosaurid (Sauropterygia, Plesiosauria) from the Bearpaw Shale (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian) of Montana demonstrates multiple evolutionary reductions of neck length within Elasmosauridae". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 37 (2): e1278608. doi:10.1080/02724634.2017.1278608.

- Sachs, S. (2005). "Redescription of Elasmosaurus platyurus, Cope 1868 (Plesiosauria: Elasmosauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous (lower Campanian) of Kansas, U.S.A". Paludicola. 5 (3): 92–106.

- F. Robin O'Keefe and Hallie P. Street (2009). "Osteology Of The Cryptoclidoid Plesiosaur Tatenectes laramiensis, With Comments On The Taxonomic Status Of The Cimoliasauridae" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (1): 48–57. doi:10.1671/039.029.0118.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Patrick S. Druckenmiller and Anthony P. Russell (2006). "A new elasmosaurid plesiosaur (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Lower Cretaceous Clearwater Formation, northeastern Alberta, Canada" (PDF). Paludicola. 5 (4): 184–199. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-06.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Benjamin P. Kear (2005). "A new elasmosaurid plesiosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Queensland, Australia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (4): 792–805. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0792:ANEPFT]2.0.CO;2.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Peggy Vincent, Nathalie Bardet, Xabier Pereda Suberbiola, Baâdi Bouya, Mbarek Amaghzaz and Saïd Meslouh (2011). "Zarafasaura oceanis, a new elasmosaurid (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Maastrichtian Phosphates of Morocco and the palaeobiogeography of latest Cretaceous plesiosaurs". Gondwana Research. 19 (4): 1062–1073. Bibcode:2011GondR..19.1062V. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2010.10.005.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Araújo, R., Polcyn M. J., Schulp A. S., Mateus O., Jacobs L. L., Gonçalves O. A., & Morais M. - L. (2015). A new elasmosaurid from the early Maastrichtian of Angola and the implications of girdle morphology on swimming style in plesiosaurs. Netherlands Journal of Geosciences. FirstView, 1–12., 1

- Serratos, Danielle J.; Druckenmiller, Patrick; Benson, Roger B. J. (2017). "A new elasmosaurid (Sauropterygia, Plesiosauria) from the Bearpaw Shale (Late Cretaceous, Maastrichtian) of Montana demonstrates multiple evolutionary reductions of neck length within Elasmosauridae". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 37 (2): e1278608. doi:10.1080/02724634.2017.1278608.

- José P. O’Gorman, Karen M. Panzeri, Marta S. Fernández, Sergio Santillana, Juan J. Moly & Marcelo Reguero (2017) A new elasmosaurid from the upper Maastrichtian López de Bertodano Formation: new data on weddellonectian diversity. Alcheringa (advance online publication) doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/03115518.2017.1339233 http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03115518.2017.1339233

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Elasmosauridae |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Elasmosauridae. |