Huastec language

The Wasteko (Huasteco) language of Mexico is spoken by the Huastecos living in rural areas of San Luis Potosí and northern Veracruz. Though relatively isolated from them, it is related to the Mayan languages spoken further south and east in Mexico and Central America. According to the 2005 population census, there are about 200,000 speakers of Huasteco in Mexico (some 120,000 in San Luis Potosí and some 80,000 in Veracruz).[3] The language and its speakers are also called Teenek, and this name has gained currency in Mexican national and international usage in recent years.

| Wastek | |

|---|---|

| Huasteco | |

| Teenek | |

| Native to | Mexico |

| Region | San Luis Potosí, Veracruz and Tamaulipas |

| Ethnicity | Huastec |

Native speakers | 161,120 (2010 census)[1] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | hus |

| Glottolog | huas1242[2] |

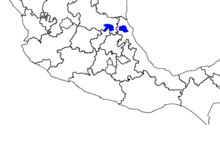

Approximate extent of Huastec-speaking area in Mexico | |

The now-extinct Chicomuceltec language, spoken in Chiapas and Guatemala, was most closely related to Wasteko.

The first linguistic description of the Huasteco language accessible to Europeans was written by Andrés de Olmos, who also wrote the first grammatical descriptions of Nahuatl and Totonac.

Wasteko-language programming is carried by the CDI's radio station XEANT-AM, based in Tancanhuitz de Santos, San Luis Potosí.

Dialects

Huasteco has three dialects, which have a time depth of no more than 400 years (Norcliffe 2003:3). It is spoken in a region of east-central Mexico known as the Huaxteca-Potossina.

- Western (Potosino) — 48,000 speakers in the 9 San Luis Potosí towns of Ciudad Valles (Tantocou), Aquismón, Huehuetlán, Tancanhuitz, Tanlajás, San Antonio, Tampamolón, Tanquian, and Tancuayalab.

- Central (Veracruz) — 22,000 speakers in the 2 northern Veracruz towns of Tempoal and Tantoyuca.

- Eastern (Otontepec) — 12,000 speakers in the 7 northern Veracruz towns of Chontla, Tantima, Tancoco, Chinampa, Naranjos, Amatlán, and Tamiahua. Also known as Southeastern Huastec. Ana Kondic (2012) reports only about 1,700 speakers, in the municipalities of Chontla (San Francisco, Las Cruces, Arranca Estacas, and Ensinal villages), Chinampa, Amatlan, and Tamiahua.[4]

Phonology

Vowels

| Short vowels | Front | Central | Back |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i [i], [ɪ] | u [ʊ] | |

| Mid | e [e], [ɛ] | o [ɔ], [ʌ] | |

| Open | a [ə], [a] |

| Long vowels | Front | Central | Back |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | ii [iː] | uu [ʊː], [uː] | |

| Mid | ee [ɛː], [eː] | oo [ɔː], [oː] | |

| Open | aa [aː] |

- /aː/ can be realized as laryngealized [a̰ː] after a glottalized consonant.

- /ʊ/ in unstressed syllables can also be heard as [ʌ].

Consonants

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Labial-velar | Glottal | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | ejective | plain | ejective | plain | ejective | plain | ejective | plain | ejective | ||||

| Nasal | m [m] | n [n] | |||||||||||

| Plosive | voiceless | p [p] | t [t] | tʼ [tʼ] | k [k] | kʼ [kʼ] | kw [kʷ] | kwʼ [kʼʷ] | ʼ [ʔ] | ||||

| aspirated | p [pʰ] | t [tʰ] | k [kʰ] | kw [kʷʰ] | |||||||||

| voiced | b [b] | (d [d]) | (kʼ [ɡ]) | (kwʼ [ɡʷ]) | |||||||||

| Affricate | voiceless | ts [ts] | tsʼ [tsʼ] | ch [tɕ] | chʼ [tɕʼ] | ||||||||

| aspirated | ts [tsʰ] | ch [tɕʰ] | |||||||||||

| Fricative | (f [f]) | z [θ] | s [s] | x [ɕ] | j [h] | ||||||||

| Approximant | w [w] | l [l] | y [j] | ||||||||||

| Flap | r [ɾ] | ||||||||||||

- Unaspirated sounds of both plosives and affricates, only occur as realizations of sounds occurring word-medially. They are realized elsewhere as aspirated. /p/ can also become voiced [b] in word-final positions.

- Sounds /f, d/ may appear from Spanish loanwords.

- The affricate sounds /ts, tsʼ/ can also be realized as [s, dz].

- /b/ can also be realized as a fricative [β], and also as a voiceless fricative [ɸ] in word-final positions.

- Ejective velar sounds /kʼ, kʼʷ/ can be realized as voiced [ɡ, ɡʷ] in word-medial positions.

- Approximant sounds /l, w, j/ can be realized as voiceless [l̥, ʍ, j̊] in word-final positions.

- /n/ before velar sounds is realized as a palatal nasal [ɲ].

- /h/ before /i/ can be realized as a velar sound [x].[5]

Notes

- INALI (2012) México: Lenguas indígenas nacionales

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Huastec". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- INEGI, 2005

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-09-28. Retrieved 2013-01-09.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Edmonson, Barbara Wedemeyer (1988). A descriptive grammar of Huastec (Potosino dialect). Tulane University.

References

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía, e Informática (INEGI) (an agency of the government of Mexico). 2005. 2005 Mexican population census, last visited 22 May, 2007

Further reading

- Ariel de Vidas, A. 2003. "Ethnicidad y cosmologia: La construccion cultural de la diferencia entre los teenek (huaxtecos) de Veracruz", in UNAM, Estudios de Cultura Maya.Vol. 23.

- Campbell, L. and T. Kaufman. 1985. "Maya linguistics: Where are we now?," in Annual Review of Anthropology. Vol. 14, pp. 187–98

- Dahlin, B. et al. 1987. "Linguistic divergence and the collapse of Preclassic civilization in southern Mesoamerica". American Antiquity. Vol. 52, No. 2, pp. 367–82.

- Edmonson, Barbara Wedemeyer. 1988. A descriptive grammar of Huastec (Potosino dialect). Ph.D. dissertation: Tulane University.

- INAH. 1988. Atlas cultural de Mexico: Linguistica. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia.

- Kaufman, T. 1976. "Archaeological and linguistic correlations in Mayaland and associated areas of Mesoamerica," in World Archaeology. Vol. 8, pp. 101–18

- Malstrom, V. 1985. "The origins of civilization in Mesoamerica: A geographic perspective", in L. Pulsipher, ed. Yearbook of the Conference of Latin Americanist Geographers. Vol. 11, pp. 23–29.

- McQuown, Norman A. 1984. A sketch of San Luis Potosí Huastec. University of Texas Press.

- (CDI). No date. San Luis Potosí: A Teenek Profile; Summary. Archived from the original on July 17, 2007.

- Norcliffe, Elizabeth. 2003. The Reconstruction of Proto-Huastecan. M.A. dissertation. University of Canterbury.

- Ochoa Peralta, María Angela. 1984. El idioma huasteco de Xiloxúchil, Veracruz. México City: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

- Ochoa, L. 2003. "La costa del Golfo y el area maya: Relaciones imaginables o imaginadas?", in UNAM, Estudios de Cultura Maya.Vol. 23.

- Robertson, J. 1993. "The origins and development of Huastec pronouns." International Journal of American Linguistics. Vol. 59, No. 3, pp. 294–314

- Sandstrom, Alan R., and Enrique Hugo García Valencia. 2005. Native peoples of the Gulf Coast of Mexico. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- Stresser-Pean, G. 1989. "Los indios huastecos", in Ochoa, L., ed. Huastecos y Totonacas. Mexico City: CONACULTA.

- Vadillo Lopez, C. and C. Riviera Ayala. 2003. "El trafico maratimo, vehiculo de relaciones culturales entre la region maya chontal de Laguna de Terminos y la region huaxteca del norte de Veracruz, siglos XVI-XIX", in UNAM, Estudios de Cultura Maya.Vol. 23.

- Wilkerson, J. 1972. Ethnogenesis of the Huastecs and Totonacs. PhD dissertation, Department of Anthropology and Archaeology, Tulane University, New Orleans.

| Huastec language test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |

External links

- Huasteco Collection of Barbara Edmonson, an archive of recordings of narratives, words, and rituals from the Archive of the Indigenous Languages of Latin America.