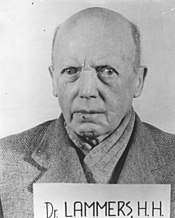

Hans Lammers

Hans Heinrich Lammers (27 May 1879 – 4 January 1962) was a German jurist and prominent Nazi politician. From 1933 until 1945 he served as Chief of the Reich Chancellery under Adolf Hitler. During the 1948–1949 Ministries Trial, Lammers was found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity and sentenced to 20 years' imprisonment.

Hans Lammers | |

|---|---|

Hans Lammers in SS uniform | |

| Chief of the Reich Chancellery | |

| In office 30 January 1933 – 24 April 1945 | |

| Deputy | Friedrich Wilhelm Kritzinger (1942-45) |

| Leader | Adolf Hitler (Führer) |

| Preceded by | Erwin Planck |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Reich Minister Without Portfolio | |

| In office 1 December 1937 – 24 April 1945 | |

| Leader | Adolf Hitler (Führer) |

| President of the Reich Cabinet (Presiding Officer in Hitler's Absence) | |

| In office January 1943 – 24 April 1945 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Hans Heinrich Lammers 27 May 1879 Lublinitz, Silesia, Prussia, German Empire |

| Died | 4 January 1962 (aged 82) Düsseldorf, West Germany |

| Political party | Nazi Party |

| Other political affiliations | DNVP until 1932 |

| Spouse(s) | Elfriede Tepel

( m. 1913; died 1945) |

| Children | 3 |

| Education | Law |

| Alma mater | German University of Breslau Heidelberg University |

| Profession | Judge |

| Cabinet | Hitler Cabinet |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | German Army |

| Battles/wars | World War I |

| Awards | Iron Cross |

Early life

Born in Lublinitz (now Lubliniec, Poland) in Upper Silesia, the son of a veterinarian, Lammers completed law school at the universities of Breslau (Wrocław) and Heidelberg, obtained his doctorate in 1904, and was appointed judge at the Amtsgericht (district court) of Beuthen (Bytom) in 1912. During World War I, as a volunteer and officer of the German Army, he received the Iron Cross, First and Second Class. After World War I he joined the national conservative German National People's Party (DNVP) and resumed his career as a lawyer reaching by 1922 the position of undersecretary at the Reich Ministry of the Interior.[1]

Nazi career

In 1932, Lammers joined the Nazi Party and achieved rapid promotions: he was appointed head of the police department, and, after the Nazi seizure of power in 1933 State Secretary and Chief of the Reich Chancellery.[2] At the recommendation of Reich Minister of the Interior Wilhelm Frick, he became the centre of communications and chief legal adviser for all government departments. From 1937, he was a member of Hitler's cabinet as a Reich Minister without portfolio, and from 30 November 1939 a member of the Council of Ministers for the Defence of the Reich.[1] In this position, he was able to review all pertinent documents regarding national security and domestic policy even before they were forwarded to Hitler in person. Historian Martin Kitchen explains that due to the centralization of power accorded to the Reich Chancellery and therefore to its head, Lammers became "one of the most important men in Nazi Germany".[3] From the vantage point of most government officers, Lammers seemed to speak on behalf of Hitler, the ultimate authority within the Reich. Lammers was also one of the first officials to sign government correspondence with "Heil Hitler", which became a requisite greeting for civil servants and eventually so ubiquitous that failure to use it was considered an "overt sign of dissidence" which could trigger attention from the Gestapo.[4] Sometime in 1940, Lammers was also promoted to honorary SS General.[1]

From January 1943, Lammers served as President of the cabinet when Hitler was absent from their meetings. Along with Martin Bormann, he increasingly controlled access to Hitler. By early 1943, the war produced a labour crisis for the regime. Hitler agreed to the creation of a three-man committee with representatives of the State, the army, and the Party in an attempt to centralise control of the war economy and over the home front. The committee members were Lammers (Chief of the Reich Chancellery), Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, chief of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (Armed Forces High Command; OKW), and Bormann, who controlled the Party.[5] Hitler seemed to be in agreement with this proposal since none of them posed a threat to his leadership nor would they disagree with him.[6] The committee was intended to independently propose measures regardless of the wishes of various ministries, with Hitler reserving most final decisions to himself. The committee, soon known as the Dreierausschuß (Committee of Three), met eleven times between January and August 1943. However, they ran up against resistance from Hitler's cabinet ministers, who headed deeply entrenched spheres of influence and were excluded from the committee. Seeing it as a threat to their power, Joseph Goebbels, Albert Speer, Hermann Göring and Heinrich Himmler worked together to bring it down. The result was that nothing changed, and the Committee of Three declined into irrelevance.[5] Over time Lammers lost power and influence because of the increasing irrelevancy of his position due to the war and as a consequence of Martin Bormann's growing influence with Hitler.[7]

1945

In April 1945, Lammers was arrested by SS troops during the final days of the Third Reich, in connection with the upheaval surrounding Hermann Göring. On 23 April, as the Soviets tightened the encirclement of Berlin, Göring consulted Luftwaffe General Karl Koller and Lammers. All agreed that Göring was not only Hitler's designated successor but was to act as his deputy if Hitler ever became incapacitated.[8] Göring concluded that, by remaining in Berlin to face certain death, Hitler had incapacitated himself from governing.[9] Acting on the matter, Göring sent a telegram from Berchtesgaden, Bavaria, arguing that since Hitler was cut off in Berlin, he, Göring, should assume leadership of Germany. Göring set a time limit of 22:00 that night (23 April), after which he would consider Hitler incapacitated. The telegram was intercepted by Bormann, who convinced Hitler that Göring was a traitor and that the telegram was a demand to resign or be overthrown. Hitler responded angrily, ordering SS troops to arrest Göring. Soon afterward, Hitler removed Göring from all of his offices and ordered Göring, his staff and Lammers placed under house arrest at Obersalzberg.[10][11] Lammers was taken prisoner by American forces,[12] but in the meantime his wife, Elfriede (née Tepel), committed suicide near Obersalzberg (the site of Hitler's mountain retreat) in early May 1945, as did his younger daughter, Ilse, two days later.[13]

Post-war insights

Following the war's conclusion, Lammers provided Allied interrogators with some insights into the nature of the Third Reich's hierarchy. Post war mythology was such that many were convinced Hitler had completely ostracized the aristocratic officers under his command, but the truth was somewhat different.[14] Lammers reported to the Allies that Nazi kingpins and high-ranking Wehrmacht officers received lavish gifts, severance packages, expropriated estates, and huge cash awards. Recipients of such benefits included Generals Heinz Guderian, Paul Ludwig Ewald von Kleist, Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb, Gerd von Rundstedt, and one of the Holocaust's chief architects, Reinhard Heydrich.[14]

Trial and conviction

In April 1946, Lammers was a witness at the Nuremberg tribunal. Starting in April 1949, he was tried in the Ministries Trial, one of the subsequent Nuremberg trials, and sentenced to 20 years in prison. The sentence was later commuted to 10 years by U.S. High Commissioner John J. McCloy, and on 16 December 1951, he was released from Landsberg Prison.[15][lower-alpha 1] Lammers died on 4 January 1962 in Düsseldorf, and was buried in Berchtesgaden in the same plot as his wife and daughter.

See also

- Bribery of senior Wehrmacht officers

- Friedrich Wilhelm Kritzinger, Lammers' deputy, who represented the Reich Chancellery at the Wannsee Conference

Notes

- There are conflicting reports about Lammers' release date. According to Zentner and Bedürftig, in The Encyclopedia of the Third Reich vol. 1 [A-L] (New York: MacMillan Publishing, 1991), p. 254, Lammers was not released until 1954. Dr. Louis Snyder has him released sometime in 1952 in Encyclopedia of the Third Reich (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1976), p. 204; Gerald Reitlinger reported Lammers free in November 1951 in The SS: Alibi of a Nation, 1922–1945 (New York: Da Capo Press, 1989), p. 470; Tim Kirk claims Lammers was released sometime in 1951 in The Longman Companion to Nazi Germany (New York: Routledge, 1995), p. 222; Roderick Stackelberg has him amnestied at an unspecified 1951 date in The Routledge Companion to Nazi Germany (New York: Routledge, 2007), p. 220, as does William Shirer in The Rise And Fall Of The Third Reich (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990), p. 965 fn.

References

Citations

- Wistrich 1995, p. 149.

- Zentner & Bedürftig 1991, p. 523.

- Kitchen 1995, p. 11.

- Evans 2006, p. 45.

- Kershaw 2008, pp. 749–753.

- Read 2005, p. 779.

- Fischer 1995, p. 312.

- Shirer 1960, p. 1,115.

- Shirer 1960, p. 1,116.

- Shirer 1960, p. 1,118.

- Evans 2008, p. 724.

- Zentner & Bedürftig 1991, p. 524.

- "Hans Heinrich Lammers". www.nndb.com.

- Hanson 2017, p. 456.

- Wistrich 2001, p. 149.

Bibliography

- Bullock, Alan (1962) [1952]. Hitler: A Study in Tyranny. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-013564-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Evans, Richard (2006). The Third Reich in Power. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-303790-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Evans, Richard J. (2008). The Third Reich at War. New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-311671-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fischer, Klaus (1995). Nazi Germany: A New History. New York: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-82640-797-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hanson, Victor Davis (2017). The Second World Wars: How the First Global Conflict Was Fought and Won. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-46506-698-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kershaw, Ian (2008). Hitler: A Biography. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06757-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kitchen, Martin (1995). Nazi Germany at War. New York: Longman. ISBN 978-0582073876.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Read, Anthony (2005). The Devil's Disciples: Hitler's Inner Circle. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-039332-697-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shirer, William L. (1960). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-62420-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wistrich, Robert (2001). Who's Who In Nazi Germany. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-41511-888-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zentner, Christian; Bedürftig, Friedemann (1991). The Encyclopedia of the Third Reich. (2 vols.) New York: MacMillan Publishing. ISBN 0-02-897500-6.CS1 maint: location (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- from The Simon Wiesenthal Center

- Newspaper clippings about Hans Lammers in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW