Vlachs

Vlachs (English: /ˈvlɑːk/ or /ˈvlæk/, or rarely /ˈvlɑːx/), also Wallachians (and many other variants[1]), is a historical term from the Middle Ages that designates an exonym, mostly for the Romanians who lived north and south of the Danube.[2]

_-_1887.jpg)

As a contemporary term, in the English language, the Vlachs are the Balkan Romance-speaking peoples who live south of the Danube in what are now eastern Serbia, southern Albania, northern Greece, North Macedonia, and southwestern Bulgaria, as indigenous ethnic groups, such as the Aromanians, Megleno-Romanians (Macedoromanians), and Macedo-Vlachs.[3] The term also became a synonym in the Balkans for the social category of shepherds,[4] and was also used for non-Romance-speaking peoples, in recent times in the western Balkans derogatively.[5] There is also a Vlach diaspora in other European countries, especially Romania, as well as in North America and Australia.[3]

"Vlachs" were initially identified and described during the 11th century by George Kedrenos. According to one origin theory, modern Romanians, Moldovans and Aromanians originated from Dacians.[6] According to some linguists and scholars, the Eastern Romance languages prove the survival of the Thraco-Romans in the lower Danube basin during the Migration Period[7] and western Balkan populations known as "Vlachs" also have had Romanized Illyrian origins.[8]

Nowadays, Eastern Romance-speaking communities are estimated at 26–30 million people worldwide (including the Romanian diaspora and Moldovan diaspora).[9]

Etymology and names

The word Vlach/Wallachian (and other variants such as Vlah, Valah, Valach, Voloh, Blac, oláh, Vlas, Ilac, Ulah, etc.[1]) is etymologically derived from the ethnonym of a Celtic tribe,[5] adopted into Proto-Germanic *Walhaz, which meant "stranger", from *Wolkā-[10] (Caesar's Latin: Volcae, Strabo and Ptolemy's Greek: Ouolkai).[11] Via Latin, in Gothic, as *walhs, the ethnonym took on the meaning "foreigner" or "Romance-speaker",[11] and was adopted into Greek Vláhi (Βλάχοι), Slavic Vlah, Hungarian oláh and olasz, etc.[12][13] The root word was notably adopted in Germanic for Wales and Walloon, and in Switzerland for Romansh-speakers (German: Welsch),[5] and in Poland Włochy or in Hungary olasz became an exonym for Italians.[11][1] The Slovenian term Lahi has also been used to designate Italians.[14]

Historically, the term was used primarily for the Romanians.[1][3] Testimonies from the 13th to 14th centuries show that, although in the European (and even extra-European) space they were called Vlachs or Wallachians (oláh in Hungarian, Vláchoi (βλάχοι) in Greek, Volóxi (воло́хи) in Russian, Walachen in German, Valacchi in Italian, Valaques in French, Valacos in Spanish), the Romanians used for themselves the endonym "Rumân/Român", from the Latin "Romanus" (in memory of Rome).[1] Vlachs are referred in late Byzantine documents as Bulgaro-Albano-Vlachs ("Bulgaralbanitoblahos"), or Serbo-Albano-Bulgaro-Vlachs[15]

Via both Germanic and Latin, the term started to signify "stranger, foreigner" also in the Balkans, where it in its early form was used for Romance-speakers, but the term eventually took on the meaning of "shepherd, nomad".[5] The Romance-speaking communities themselves however used the endonym (they called themselves) "Romans".[16] Term Vlach can denote various ethnic elements: "Slovak, Hungarian, Balkan, Transylvanian, Romanian, or even Albanian". [17]

During the early history of the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans, there was a military class of Vlachs in Serbia and Ottoman Macedonia, made up of Christians who served as auxiliary forces and had the same rights as Muslims, but their origin is not entirely clear.[4] Some Greeks used “vlachos” as a pejorative term. The term "Vlachs" can be used in the whole Balkan area in derogatory way because nomads are traditionally considered "dirty" and "aggressive". Some Croats used that term for Serbs, the city dwellers, the country people and so on.[18] While the Hapsburgs called all Orthodox settlers Vlachs.[19] [20] In Bosnia and Herzegovina the Bosnians called inhabitants of Dubrovnik as Vlachs, in Žumberak members of the Greek Catholic Church were called Vlachs, in Carniola residents of Žumberak in general were Vlachs. In Posavina and Bihać area Muslims called Vlachs as Christians (both Orthodox and Catholics) while Catholics under that name consider Orthodox Christians. For residents of the Dalmatian islands Vlachs are population which live in the Biokovo area, Kajkavian inhabitants of northwestern Croatia all Shtokavian immigrants (either Croats or Serbs) call as Vlachs. The name Vlach in Dalmatia also has negative connotations ie "newcomer", "peasant", "ignorant" while in Istria the ethnonym Vlach is used to make a distinction between the native Croats and newly settled Istro-Romanian and Slavic population which coming in the 15th and 16th century.[21]

Romanian scholars have suggested that the term Vlach appeared for the first time in the Eastern Roman Empire and was subsequently spread to the Germanic- and then Slavic-speaking worlds through the Norsemen (possibly by Varangians), who were in trade and military contact with Byzantium during the early Middle Ages (see also Blakumen).[22][23]

Nowadays, the term Vlachs (also known under other names, such as "Koutsovlachs", "Tsintsars", "Karagouni", "Chobani", "Vlasi", etc.[24]) is used in scholarship for the Romance-speaking communities in the Balkans, especially those in Greece, Albania and North Macedonia.[25][26] In Serbia the term Vlach (Serbian Vlah, plural Vlasi) is also used to refer to Romanian speakers, especially those living in eastern Serbia.[3] Aromanians themselves use the endonym "Armãn" (plural "Armãni") or "Rãmãn" (plural "Rãmãni"), etymologically from "Romanus", meaning "Roman". Megleno-Romanians designate themselves with the Macedonian form Vla (plural Vlaš) in their own language.[3]

Medieval usage

The Hellenic chronicle could possibly qualify to the first testimony of Vlachs in Pannonia and Eastern Europe during the time of Attila.[27][28][29]

6th century

Byzantine historians used the term Vlachs for Latin speakers.[30][31][32]

The 7th century Byzantine historiographer Theophylact Simocatta wrote about “Blachernae” in connection with some historical data of the 6th century, during the reign of Byzantine Emperor Maurice.[33]

8th century

First precise data about Vlachs are in connection with the Vlachs of the Rynchos river; the original document containing the information is from the Konstamonitou monastery.[34]

9th century

During the late 9th century the Hungarians invaded the Carpathian Basin, where the province of Pannonia was inhabited by the "Slavs [Sclavi], Bulgarians [Bulgarii] and Vlachs [Blachii], and the shepherds of the Romans [pastores Romanorum]" (sclauij, Bulgarij et Blachij, ac pastores romanorum —according to the Gesta Hungarorum, written around 1200 by the anonymous chancellor of King Béla III of Hungary.[35]

10th century

Chroniclers John Skylitzes and George Kedrenos wrote that in 971, during battles between Romans and Varangians led by Sveinald (Sviatoslav), the dwellers of North side of Danube came to Emperor John I Tzimiskes and they handed over their fortresses and the Emperor sent troops to guard the fortresses. During those times, Northern part of Danube were dwelled by sedentary Vlachs and tribes of nomad Pechenegs who lived in tents.[36]

George Kedrenos mentioned about Vlachs in 976. The Vlachs were guides and guards of Roman caravans in Balkans. Between Prespa and Kastoria they met and fought with a Bulgarian rebel named David. The Vlachs killed David in their first documented battle.

Mutahhar al-Maqdisi, "They say that in the Turkic neighbourhood there are the Khazars, Russians, Slavs, Waladj, Alans, Greeks and many other peoples."[37]

Ibn al-Nadīm published in 938 the work “Kitāb al-Fihrist” mentioning “Turks, Bulgars and Vlahs” (using Blagha for Vlachs)[38][39]

11th century

Byzantine writer Kekaumenos, author of the Strategikon (1078), described a 1066 revolt against the emperor in Northern Greece led by Nicolitzas Delphinas and other Vlachs.[40]

The names Blakumen or Blökumenn is mentioned in Nordic sagas dating between the 11th–13th centuries, with respect to events that took place in either 1018 or 1019 somewhere at the northwestern part of the Black Sea and believed by some to be related to the Vlachs.[41][42]

In the Bulgarian state of the 11th and 12th century, Vlachs live in large numbers, and they where equals to the Bulgarian population.[43]

12th century

The Russian Primary Chronicle, written in ca. 1113, wrote when the Volochi (Vlachs) attacked the Slavs of the Danube and settled among them and oppressed them, the Slavs departed and settled on the Vistula, under the name of Leshi.[44] The Hungarians drove away the Vlachs and took the land and settled there.[45][46]

Traveler Benjamin of Tudela (1130–1173) of the Kingdom of Navarre was one of the first writers to use the word Vlachs for a Romance-speaking population.[47]

Byzantine historian John Kinnamos described Leon Vatatzes' military expedition along the northern Danube, where Vatatzes mentioned the participation of Vlachs in battles with the Magyars (Hungarians) in 1166.[48][49]

The uprising of brothers Asen and Peter was a revolt of Bulgarians and Vlachs living in the theme of Paristrion of the Byzantine Empire, caused by a tax increase. It began on 26 October 1185, the feast day of St. Demetrius of Thessaloniki, and ended with the creation of the Second Bulgarian Empire, also known in its early history as the Empire of Bulgarians and Vlachs.

13th century

In 1213 an army of Romans (Vlachs), Transylvanian Saxons, and Pechenegs, led by Ioachim of Sibiu, attacked the Bulgars and Cumans from Vidin.[50] After this, all Hungarian battles in the Carpathian region were supported by Romance-speaking soldiers from Transylvania.[51]

At the end of the 13th century, during the reign of Ladislaus the Cuman, Simon de Kéza wrote about the Blacki people and placed them in Pannonia with the Huns.[52][53] Archaeological discoveries indicate that Transylvania was gradually settled by the Magyars, and the last region defended by the Vlachs and Pechenegs (until 1200) was between the Olt River and the Carpathians.[54][55]

Shortly after the fall of the Olt region, a church was built at the Cârța Monastery and Catholic German-speaking settlers from Rhineland and Mosel Valley (known as Transylvanian Saxons) began to settle in the Orthodox region.[56] In the Diploma Andreanum issued by King Andrew II of Hungary in 1224, "silva blacorum et bissenorum" was given to the settlers.[57] The Orthodox Vlachs spread further northward along the Carpathians to Poland, Slovakia, and Moravia and were granted autonomy under Ius Vlachonicum (Walachian law).[58]

In 1285 Ladislaus the Cuman fought the Tatars and Cumans, arriving with his troops at the Moldova River. A town, Baia (near the said river), was documented in 1300 as settled by the Transylvanian Saxons (see also Foundation of Moldavia).[59][60] In 1290 Ladislaus the Cuman was assassinated; the new Hungarian king allegedly drove voivode Radu Negru and his people across the Carpathians, where they formed Wallachia along with its first capital Câmpulung (see also Foundation of Wallachia).[61]

14th century

The biggest caravan shipment between Podvisoki in Bosnia and Republic of Ragusa was recorded on August 9, 1428 where Vlachs transported 1500 modius of salt with 600 horses.[62][63] In the 14th century royal charters include and some segregation policies declaring that "a Serb shall not marry a Vlach."[64]

Toponymy

In addition to the ethnic groups of Aromanians, Megleno-Romanians, and Istro-Romanians who emerged during the Migration Period, other Vlachs could be found as far north as Poland, as far west as Moravia and Dalmatia.[65] In search of better pasture, they were called Vlasi or Valaši by the Slavs. States mentioned in medieval chronicles were:

- Wallachia – between the Southern Carpathians and the Danube (Ţara Românească in Romanian); Bassarab-Wallachia (Bassarab's Wallachia and Ungro-Wallachia or Wallachia Transalpina in administrative sources; Istro-Vlachia (Danubian Wallachia in Byzantine sources), and Velacia secunda on Spanish maps

- Moldavia – between the Carpathians and the Dniester river (Bogdano-Wallachia; Bogdan's Wallachia, Moldo-Wallachia or Maurovlachia; Black Wallachia, Moldovlachia or Rousso-Vlachia in Byzantine sources); Bogdan Iflak or Wallachia in Polish sources; L'otra Wallachia (the other Wallachia) in Genovese sources and Velacia tertia on Spanish maps

- Transylvania – between the Carpathians and the Hungarian plain; Wallachia interior in administrative sources and Velacia prima on Spanish maps

- Second Bulgarian Empire, between the Carpathians and the Balkan Mountains – Regnum Bulgarorum et Blachorum in documents by Pope Innocent III

- Terra Prodnicorum (or Terra Brodnici), mentioned by Pope Honorius III in 1222. Vlachs led by Ploskanea supported the Tatars in the 1223 Battle of Kalka. Vlach lands near Galicia in the west, Volhynia in the north, Moldova in the south and the Bolohoveni lands in the east were conquered by Galicia.[66]

- Bolokhoveni was Vlach land between Kiev and the Dniester in Ukraine. Place names were Olohovets, Olshani, Voloschi and Vlodava, mentioned in 11th-to-13th-century Slavonic chronicles. It was conquered by Galicia.[67]

Regions and places are:

- White Wallachia in Moesia[68]

- Great Wallachia (Μεγάλη Βλαχία; Megáli vlahía) in Thessaly[68]

- Small Wallachia (Μικρή Βλαχία; Mikrí vlahía) in Aetolia, Acarnania, Dorida and Locrida[68]

- Morlachia, in Lika-Dalmatia

- Upper Valachia of Moscopole and Metsovon (Άνω Βλαχία; Áno Vlahía) in southern Macedonia, Albania and Epirus

- Stari Vlah ("the Old Vlach"), a region in southwestern Serbia

- Romanija mountain (Romanija planina) in eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina[69]

- Vlaşca County, a former county of southern Wallachia (derived from Slavic Vlaška)

- Greater Wallachia, an older name for the region of Muntenia, southeastern Romania

- Lesser Wallachia, an older name for the region of Oltenia, southwestern Romania

- An Italian writer called the Banat Valachia citeriore ("Wallachia on this side") in 1550.[70]

- Valahia transalpina, including Făgăraș and Haţeg

- Moravian Wallachia (Czech: Moravské Valašsko), in the Beskid Mountains (Czech: Beskydy) of the Czech Republic.[71]

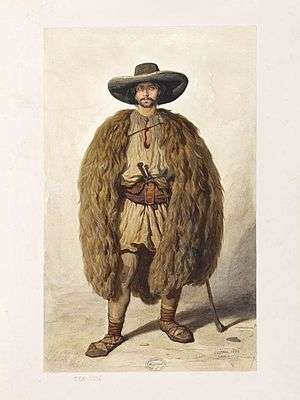

Shepherd culture

As national states appeared in the area of the former Ottoman Empire, new state borders were developed that divided the summer and winter habitats of many of the pastoral groups. During the Middle Ages, many Vlachs were shepherds who drove their flocks through the mountains of Central and Eastern Europe. Vlach shepherds may be found as far north as southern Poland (Podhale) and the eastern Czech Republic (Moravia) by following the Carpathians, the Dinaric Alps in the west, the Pindus Mountains in the south, and the Caucasus Mountains in the east.[72]

Some researchers, like Bogumil Hrabak and Marian Wenzel, theorized that the origins of Stećci tombstones, which appeared in medieval Bosnia between 12th and 16th century, could be attributed to Vlach burial culture of Bosnia and Herzegovina of that times.[73]

Medieval necropolis in Radimlja, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

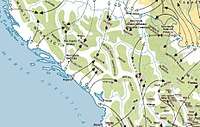

Medieval necropolis in Radimlja, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Detailed map depicting Vlach transhumance in the Western Balkans, showcasing several examples of Vlach necropolises.[74]

Detailed map depicting Vlach transhumance in the Western Balkans, showcasing several examples of Vlach necropolises.[74]

Legacy

According to Ilona Czamańska "for several recent centuries the investigation of the Vlachian ethnogenesis was so much dominated by political issues that any progress in this respect was incredibly difficult." Migration of the Vlachs may be the key for solving the problem of ethno genesis, but the problem is that many migrations were in multiple directions during the same time. These migrations were not just part of the Balkans and the Carpathians, they exist and in the Caucasus, the Adriatic islands and possibly over the entire region of the Mediterranean Sea. Because of this, our knowledge concerning primary migrations of the Vlachs and the ethnogenesis is more than modes.[75]

See also

Notes

- Ioan-Aurel Pop. "On the Significance of Certain Names: Romanian/Wallachian and Romania/Wallachia" (PDF). Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- "Valah". Dicționare ale limbii române. dexonline.ro. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- Vlach at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Peter F. Sugar (1 July 2012). Southeastern Europe under Ottoman Rule, 1354–1804. University of Washington Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-295-80363-0.

- Tanner 2004, p. 203.

- Fine 1991, p. ?: "Traditionally scholars have seen the Dacians as ancestors of the modern Rumanians and Vlachs."

- According to Cornelia Bodea, Ştefan Pascu, Liviu Constantinescu: "România: Atlas Istorico-geografic", Academia Română 1996, ISBN 973-27-0500-0, chap. II, "Historical landmarks", p. 50 (English text), the survival of the Thraco-Romans in the Lower Danube basin during the Migration Period is an obvious fact: Thraco-Romans haven't vanished in the soil & Vlachs haven't appeared after 1000 years by spontaneous generation.

- Badlands-Borderland: A History of Southern Albania/Northern Epirus [ILLUSTRATED] (Hardcover) by T. J. Winnifruth, ISBN 0-7156-3201-9, 2003, page 44: "Romanized Illyrians, the ancestors of the modern Vlachs".

- "Council of Europe Parliamentary Recommendation 1333 (1997)". Assembly.coe.int. 24 June 1997. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- Ringe, Don. "Inheritance versus lexical borrowing: a case with decisive sound-change evidence." Language Log, January 2009.

- Juhani Nuorluoto; Martti Leiwo; Jussi Halla-aho (2001). Papers in Slavic, Baltic, and Balkan studies. Dept. of Slavonic and Baltic Languages and Literatures, University of Helsinki. ISBN 978-952-10-0246-5.

- Kelley L. Ross (2003). "Decadence, Rome and Romania, the Emperors Who Weren't, and Other Reflections on Roman History". The Proceedings of the Friesian School. Retrieved 13 January 2008.

Note: The Vlach Connection

- Entangled Histories of the Balkans: Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies. BRILL. 13 June 2013. pp. 42–. ISBN 978-90-04-25076-5.

- Thomas M. Wilson; Hastings Donnan (2005). Culture and Power at the Edges of the State: National Support and Subversion in European Border Regions. LIT Verlag Münster. pp. 122–. ISBN 978-3-8258-7569-5.

- Noel Malcolm; (1996) Bosnia: A Short History p. 101; NYU Press, ISBN 0814755615

- H. C. Darby (1957). "The face of Europe on the eve of the great discoveries". The New Cambridge Modern History. 1. p. 34.

- Jan Gawron; (2020) Locators of the settlements under Wallachian law in the Sambor starosty in XVth and XVIth c. Territorial, ethnic and social origins. p. 274-275; BALCANICA POSNANIENSIA xxVI,

- Tanner 2004, p. 203-204.

- Trbovich, Ana. A legal geography of Yugoslavia's disintegration. Oxford Univ Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-19-533343-5.

- Šarić 2009, p. 333.

- Spicijarić Paškvan, Nina; (2014) Vlasi i krčki Vlasi u literaturi i povijesnim izvorima (Vlachs from the Island Krk in the Primary Historical and Literature Sources) p. 348; Studii şi cercetări – Actele Simpozionului Banat – istorie şi multiculturalitate,

- Ilie Gherghel, Câteva considerațiuni la cuprinsul noțiunii cuvântului "Vlach", București: Convorbiri Literare, 1920, p. 4-8.

- G. Popa Lisseanu, Continuitatea românilor în Dacia, Editura Vestala, Bucuresti, 2014, p.78

- The Balkan Vlachs: Born to Assimilate? at culturalsurvival.org

- Demirtaş-Coşkun 2001.

- Tanner 2004.

- Dvoichenko-Markov, Demetrius. “THE RUSSIAN PRIMARY CHRONICLE AND THE VLACHS OF EASTERN EUROPE.” Byzantion, vol. 49, 1979, pp. 175–187. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/44172681. Accessed 3 Apr. 2020.

- O. V. Tvorogov, Drevne-Russkie Chronography (Ancient Russian Chronographies), Leningrad, 1975, p.138.

- P. P. Panaitescu, Introducere la Istoria Culturii Romànesti (Introduction to the History of Rumanian Culture), Bucharest, 1969, p. 130

- A. ARMBRUSTER, ROMANITATEA ROMÂNILOR ISTORIA UNEI IDEI, Editura Enciclopedica,1993

- http://www.farsarotul.org/nl26_1.htm

- http://www.friesian.com/decdenc2.htm

- Theophylact Simocatta, 8.4.11-8.5.4 (Publisher. C. de Boer, 1972)

- Stelian Brezeanu, O istorie a Bizanțului, Editura Meronia, București, 2005, p.126

-

- Gesta Hungarorum (a translation by Martyn Rady)

- FHDR, Fontes Historiae Daco-Romaniae-Izvoarele istoriei României, vol. III, p. 141

- A. Decei, V. Ciocîltan, “La mention des Roumains (Walah) chez Al-Maqdisi,”in Romano-arabica I, Bucharest, 1974, pp. 49–54

- Ibn al Nadim, al-Fihrist. English translation: The Fihrist of al-Nadim. Editor și traducător: B. Dodge, New York, Columbia University Press, 1970, p. 37 with n.82

- Spinei, Victor, The Romanians and the Turkic Nomads North of the Danube Delta from the Tenth to the Mid-Thirteenth Century. Brill. 2009, p.83

- G. Murnu, Când si unde se ivesc românii întâia dată în istorie, în „Convorbiri Literare”, XXX, pp. 97-112

- Egils saga einhenda ok Ásmundar berserkjabana, in Drei lygisogur, ed. Å. Lagerholm (Halle/Saale, 1927), p. 29

- V. Spinei, The Romanians and the Turkic Nomads North of the Danube Delta from the Tenth to the Mid-Thirteenth Century, Brill, 2009, p. 106, ISBN 9789047428800

- Andre Du Nay; (1996) The Origins of the Rumanians: The Early History of the Rumanian Language p. 31; Matthias Corvinus Publishing, ISBN 1882785088

- HE RUSSIAN PRIMARY CHRONICLE AND THE VLACHS OF EASTERN EUROPE- Demetrius Dvoichenko-Markov Byzantion Vol. 49 (1979), pp. 175-187, Peeters Publishers

- Samuel Hazzard Cross et Olgerd P. Sherbowitz-Wetzor (English), The Russian Primary Chronicle. Laurentian Text, The Medieval Academy of America, CambridgeMassachusetts, 2012, p.62

- C. A. Macartney, The Habsburg Empire: 1790-1918, Faber & Faber, 4 sept. 2014, paragraf.185

- http://users.clas.ufl.edu/fcurta/tudela.html. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - A. Decei, op. cit., p. 25.

- V. Spinei, The Romanians and the Turkic Nomads North of the Danube Delta From the Tenth to the Mid-Thirteenth Century, Brill, 2009, p.132, ISBN 9789004175365

- Curta, 2006, p. 385

- Ş. Papacostea, Românii în secolul al XIII-lea între cruciată şi imperiul mongol, Bucureşti, 1993, 36; A. Lukács, Ţara Făgăraşului, 156; T. Sălăgean, Transilvania în a doua jumătate a secolului al XIII-lea. Afirmarea regimului congregaţional, Cluj-Napoca, 2003, 26-27

- Simon de Kéza, Gesta Hunnorum et Hungarorum, IV,

- G. Popa-Lisseanu, Izvoarele istoriei Românilor, IV, Bucuresti, 1935, p. .32

- K. HOREDT, Contribuţii la istoria Transilvaniei în secolele IV-XIII, Bucureşti, 1958, p.109-131. IDEM, Siebenburgen im Fruhmittelalter, Bonn, 1986, p.111 sqq.

- I.M.Tiplic, CONSIDERAŢII CU PRIVIRE LA LINIILE ÎNTĂRITE DE TIPUL PRISĂCILOR DIN TRANSILVANIA(sec. IX-XIII)*ACTA TERRAE SEPTEMCASTRENSIS I, pp 147-164

- A. IONIŢĂ, Date noi privind colonizarea germană în Ţara Bârsei şi graniţa de est a regatului maghiar în cea de a doua jumătate a secolului al XII-lea, în RI, 5, 1994, 3-4.

- J. DEER, Der Weg zur Goldenen Bulle Andreas II. Von 1222, în Schweizer Beitrage zur Allgemeinen Geschichte, 10, 1952, pp. 104-138

- Stefan Pascu: A History of Transylvania, Wayne State Univ Pr, 1983, p. 57

- Pavel Parasca, Cine a fost "Laslău craiul unguresc" din tradiţia medievală despre întemeierea Ţării Moldovei [=Who was "Laslău, Hungarian king" of the medieval tradition on the foundation of Moldavia]. In: Revista de istorie şi politică, An IV, Nr. 1.; ULIM;2011 ISSN 1857-4076

- O. Pecican, Dragoș-vodă - originea ciclului legendar despre întemeierea Moldovei. În „Anuarul Institutului de Istorie și Arheologie Cluj”. T. XXXIII. Cluj-Napoca, 1994, pp. 221-232

- D. CĂPRĂROIU, ON THE BEGINNINGS OF THE TOWN OF CÂMPULUNG, ″Historia Urbana″, t. XVI, nr. 1-2/2008, pp. 37-64

- Kurtović, Esad. "Esad Kurtović, Konj u srednjovjekovnoj Bosni, Filozofski fakultet, Sarajevo 2014": 205. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - „Crainich Miochouich et Stiepanus Glegieuich ad meliustenendem super se et omnia eorum bona se obligando promiserunt ser Тhome de Bona presenti et acceptanti conducere et salauum dare in Souisochi in Bosna Dobrassino Veselcouich nomine dicti ser Тhome modia salis mille quingenta super equis siue salmis sexcentis. Et dicto sale conducto et presentato suprascripto Dobrassino in Souisochi medietatem illius salis dare et mensuratum consignare dicto Dobrassino. Et aliam medietatem pro eorum mercede conducenda dictum salem pro ipsius conductoribus retinere et habere. Promittentes vicissim omnia et singularia suprascripta firma et rata habere et tenere ut supra sub obligatione omnium suorum bonorum. Renuntiando” (09.08. 1428.g.), Div. Canc., XLV, 31v.

- Sima Ćirković; (2004) The Serbs p. 130; Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 0631204717

- Hammel, E. A. and Kenneth W. Wachter. "The Slavonian Census of 1698. Part I: Structure and Meaning, European Journal of Population". University of California.

- A. Boldur, Istoria Basarabiei, Editura Victor Frunza, Bucuresti 1992, pp 98-106

- A. Boldur, Istoria Basarabiei, Editura Victor Frunza, Bucuresti 1992

- Since Theophanes Confessor and Kedrenos, in : A.D. Xenopol, Istoria Românilor din Dacia Traiană, Nicolae Iorga, Teodor Capidan, C. Giurescu : Istoria Românilor, Petre Ș. Năsturel Studii și Materiale de Istorie Medie, vol. XVI, 1998

- Map of Yugoslavia, file East, sq. B/f, Istituto Geografico de Agostini, Novara, in : Le Million, encyclopédie de tous les pays du monde, vol. IV, ed. Kister, Geneve, Switzerland, 1970, pp. 290-291, and many other maps & old atlases - these names disappear after 1980.

- Mircea Mușat; Ion Ardeleanu (1985). From Ancient Dacia to Modern Romania. Editura Științifică și Enciclopedică.

that in 1550 a foreign writer, the Italian Gromo, called the Banat "Valachia citeriore" (the Wallachia that stands on this side).

- Z. Konečný, F. Mainus, Stopami minulosti: Kapitoly z dějin Moravy a Slezska/Traces of the Past: Chapters from the History of Moravia and Silesia, Brno:Blok,1979

- Silviu Dragomir: "Vlahii din nordul peninsulei Balcanice în evul mediu"; 1959, p. 172

- Marian Wenzel, "Bosnian and Herzegovinian Tombstobes—Who Made Them and Why?" Sudost-Forschungen 21 (1962): 102–143

- Anca & N.S. Tanașoca, Unitate romanică și diversitate balcanică, Editura Fundației Pro, 2004

- Ilona Czamańska; (2015) The Vlachs – several research problems p. 14; BALCANICA POSNANIENSIA XXII/1 IUS VALACHICUM I,

References

- Birgül Demirtaş-Coşkun; Ankara University. Center for Eurasian Strategic Studies (2001). The Vlachs: a forgotten minority in the Balkans. Frank Cass.

- Tanner, Arno (2004). The Forgotten Minorities of Eastern Europe: The History and Today of Selected Ethnic Groups in Five Countries. East-West Books. pp. 203–. ISBN 978-952-91-6808-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Theodor Capidan, Aromânii, dialectul aromân. Studiul lingvistic ("Aromanians, Aromanian dialect, Linguistic Study"), Bucharest, 1932

- Victor A. Friedman, "The Vlah Minority in Macedonia: Language, Identity, Dialectology, and Standardization" in Selected Papers in Slavic, Balkan, and Balkan Studies, ed. Juhani Nuoluoto, et al. Slavica Helsingiensa:21, Helsinki: University of Helsinki. 2001. 26–50. full text Though focussed on the Vlachs of North Macedonia, has in-depth discussion of many topics, including the origins of the Vlachs, their status as a minority in various countries, their political use in various contexts, and so on.

- Asterios I. Koukoudis, The Vlachs: Metropolis and Diaspora, 2003, ISBN 960-7760-86-7

- George Murnu, Istoria românilor din Pind, Vlahia Mare 980–1259 ("History of the Romanians of the Pindus, Greater Vlachia, 980–1259"), Bucharest, 1913

- Ilie Gherghel, Câteva consideraţiuni la cuprinsul noţiunii cuvântului "Vlach". Bucuresti: Convorbiri Literare,(1920).

- Nikola Trifon, Les Aroumains, un peuple qui s'en va (Paris, 2005) ; Cincari, narod koji nestaje (Beograd, 2010)

- Steriu T. Hagigogu, "Romanus şi valachus sau Ce este romanus, roman, român, aromân, valah şi vlah", Bucharest, 1939

- G. Weigand, Die Aromunen, Bd.Α΄-B΄, J. A. Barth (A.Meiner), Leipzig 1895–1894.

- A. Keramopoulos, Ti einai oi koutsovlachoi [What are the Koutsovlachs?], publ 2 University Studio Press, Thessaloniki 2000.

- A.Hâciu, Aromânii, Comerţ. Industrie. Arte. Expasiune. Civiliytie, tip. Cartea Putnei, Focşani 1936.

- Τ. Winnifrith, The Vlachs. The History of a Balkan People, Duckworth 1987

- A. Koukoudis, Oi mitropoleis kai i diaspora ton Vlachon [Major Cities and Diaspora of the Vlachs], publ. University Studio Press, Thessaloniki 1999.

- Th Capidan, Aromânii, Dialectul Aromân, ed2 Εditură Fundaţiei Culturale Aromâne, Bucureşti 2005

Further reading

- Theodor Capidan, Aromânii, dialectul aromân. Studiul lingvistic ("Aromanians, The Aromanian dialect. A Linguistic Study"), Bucharest, 1932

- Gheorghe Bogdan, MEMORY, IDENTITY, TYPOLOGY: AN INTERDISCIPLINARY RECONSTRUCTION OF VLACH ETHNOHISTORY, B.A., University of British Columbia, 1992

- Adina Berciu-Drăghicescu, Aromâni, meglenoromâni, istroromâni : aspecte identitare şi culturale, Editura Universităţii din Bucureşti, 2012, ISBN 978-606-16-0148-6

- Victor A. Friedman, "The Vlah Minority in Macedonia: Language, Identity, Dialectology, and Standardization" in Selected Papers in Slavic, Balkan, and Balkan Studies, ed. Juhani Nuoluoto, et al. Slavica Helsingiensa:21, Helsinki: University of Helsinki. 2001. 26–50. full text Though focussed on the Vlachs of North Macedonia, has in-depth discussion of many topics, including the origins of the Vlachs, their status as a minority in various countries, their political use in various contexts, and so on.

- Asterios I. Koukoudis, The Vlachs: Metropolis and Diaspora, 2003, ISBN 960-7760-86-7

- George Murnu, Istoria românilor din Pind, Vlahia Mare 980–1259 ("History of the Romanians of the Pindus, Greater Vlachia, 980–1259"), Bucharest, 1913

- Nikola Trifon, Les Aroumains, un peuple qui s'en va (Paris, 2005) ; Cincari, narod koji nestaje (Beograd, 2010)

- Steriu T. Hagigogu, "Romanus şi valachus sau Ce este romanus, roman, român, aromân, valah şi vlah", Bucharest, 1939

- Franck Vogel, a photo-essay on the Valchs published by GEO magazine (France), 2010.

- John Kennedy Campbell, 'Honour Family and Patronage' A Study of Institutions and Moral Values in a Greek Mountain Community, Oxford University Press, 1974

- The Watchmen, a documentary film by Alastair Kenneil and Tod Sedgwick (USA) 1971 describes life in the Vlach village of Samarina in Epiros, Northern Greece

External links

| Look up Vlach in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vlachs. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Vlachs. |

- ROMÂNII BALCANICI AROMÂNII—Maria Magiru about Aromanians (in Romanian)

- The Vlach Connection and Further Reflections on Roman History

- Orbis Latinus: Wallachians, Walloons, Welschen

- Vlachs in Greece

- Cultural appropriation of Vlachs' heritage

- French Vlachs Association (in Vlach, EN and FR)

- Studies on the Vlachs, by Asterios Koukoudis

- Vlachs' in Greece (in Greek)

- Consiliul A Tinirlor Armanj, Youth Aromanian community and their Projects (in Vlach, EN and RO)

- Vlach in Serbia, Online Since 1999 (in Vlach, EN and RO)

- Old Wallachia—a short Czech film from 1955 depicting life of Vlachs in Czech Moravia