Volga Finns

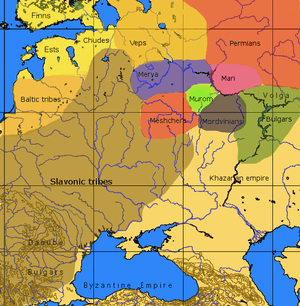

The Volga Finns (sometimes referred to as Eastern Finns)[1] are a historical group of indigenous peoples of Russia living in the vicinity of the Volga, who speak Uralic languages. Their modern representatives are the Mari people, the Erzya and the Moksha Mordvins,[2][3] as well as extinct Merya, Muromian and Meshchera people.[4] The Permians are sometimes also grouped as Volga Finns.

The modern representatives of Volga Finns live in the basins of the Sura and Moksha rivers, as well as (in smaller numbers) in the interfluve between the Volga and the Belaya rivers. The Mari language has two dialects, the Meadow Mari and the Hill Mari.

Traditionally the Mari and the Mordvinic languages (Erzya and Moksha) were considered to form a Volga-Finnic or Volgaic group within the Uralic language family,[5][6][7] accepted by linguists like Robert Austerlitz (1968), Aurélien Sauvageot & Karl Heinrich Menges (1973) and Harald Haarmann (1974), but rejected by others like Björn Collinder (1965) and Robert Thomas Harms (1974).[8] This grouping has also been criticized by Salminen (2002), who suggests it may be simply a geographic, not a phylogenetic, group.[9] Since 2009 the 16th edition of Ethnologue: Languages of the World has adopted a classification grouping Mari and Mordvin languages as separate branches of the Uralic language family.[10]

Terminology

The Volga Finns are not to be confused with the Finns. The term is a back-derivation from the linguistic term "Volga-Finnic", which in turn reflects an older usage of the term "Finnic", applying to most or the whole of the Finno-Permic group, while the group nowadays known as Finnic were referred to as "Baltic-Finnic".

Mari

The Mari or Cheremis (Russian: черемисы, Tatar Çirmeş) have traditionally lived along the Volga and Kama rivers in Russia. The majority of Maris today live in the Mari El Republic, with significant populations in the Tatarstan and Bashkortostan republics. The Mari people consists of three different groups: the Meadow Mari, who live along the left bank of the Volga, the Mountain Mari, who live along the right bank of the Volga, and Eastern Mari, who live in the Bashkortostan republic. In the 2002 Russian census, 604,298 people identified themselves as "Mari," with 18,515 of those specifying that they were Mountain Mari and 56,119 as Eastern Mari. Almost 60% of Mari lived in rural areas.[11]

Merya

The Merya people (Russian: меря; also Merä) inhabited a territory corresponding roughly to the present-day area of the Golden Ring or Zalesye regions of Russia, including the modern-day Moscow, Yaroslavl, Kostroma, Ivanovo, and Vladimir oblasts.

In the 6th century Jordanes mentioned them briefly (as Merens); later the Primary Chronicle described them in more detail. Soviet archaeologists believed that the capital of the Merya was Sarskoe Gorodishche near the bank of the Nero Lake to the south of Rostov. They are thought to have been peacefully assimilated by the East Slavs after their territory became incorporated into Kievan Rus' in the 10th century.[12]

One hypothesis classifies the Merya as a western branch of the Mari people rather than as a separate tribe. Their ethnonyms are basically identical, Merya being a Russian transcription of the Mari self-designation, Мäрӹ (Märӛ).[13]

The unattested Merya language[14] is traditionally assumed to have been a member of the Volga-Finnic group.[12][15] This view has been challenged: Eugene Helimski supposes that the Merya language was closer to the "northwest" group of Finno-Ugric (Balto-Finnic and Sami),[16] and Gábor Bereczki supposes that the Merya language was a part of the Balto-Finnic group.[17]

Some of the inhabitants of several districts of Kostroma and Yaroslavl present themselves as Meryan, although in recent censuses, they were registered as Russians. The modern Merya people have their own websites[18][19] displaying their flag, coat of arms and national anthem,[20] and participate in discussions on the subject in Finno-Ugric networks.

2010 saw the release of the film Ovsyanki (literal translation: 'The Buntings', English title: Silent Souls), based on the novel of the same name,[21] devoted to the imagined life of modern Merya people.

In recent years, a new type of social movement, the so-called "Ethnofuturism of Merya", has emerged. It is distributed in the central regions of Russia, for example, in Moscow, Pereslavl-Zalessky, Kostroma, and Ples. In October 2014, adopted the 50-minute presentation "Merya Language" III Festival of Languages at the University Novgorod. In May 2014 the "New Gallery" in the city of Ivanovo during the "Night of Museums" opened the art project mater "Volga, Sacrum".[22]

Meshchera

The Meshchera (Russian: Мещёра, Meshchyora) lived in the territory between the Oka River and the Klyazma river. It was a land of forests, bogs and lakes. The area is still called the Meshchera Lowlands.

The first Russian written source which mentions them is the Tolkovaya Paleya, from the 13th century. They are also mentioned in several later Russian chronicles from the period before the 16th century. This is in stark contrast to the related tribes Merya and Muroma, which appear to have been assimilated by the East Slavs by the 10th and the 11th centuries. Ivan II, prince of Moscow, wrote in his will, 1358, about the village Meshcherka, which he had bought from the native Meshcherian chieftain Alexander Ukovich. The village appears to have been converted to the Christian Orthodox faith and to have been a vassal of Muscovy.

The Meschiera (along with Mordua, Sibir, and a few other harder-to-interpret groups) are mentioned in the "Province of Russia" on the Venetian Fra Mauro Map (ca. 1450).[23]

Several documents mention the Meshchera concerning the Kazan campaign by Ivan the Terrible in the 16th century. These accounts concern a state of Meshchera (known under a tentative name of Temnikov Meshchera, after its central town of Temnikov) which had been assimilated by the Mordvins and the Tatars. Prince A. M. Kurbsky wrote that the Mordvin language was spoken in the lands of the Meshchera.

In the village of Zhabki (Egorievsk district, Moscow Oblast), Meshchera burial sites were found in 1870. Women's bronze decorations identified as Finno-Ugric were found and dated to the 5th to 8th centuries. Very similar finds soon appeared in the Ryazan Oblast and the Vladimir Oblast, enabling archaeologists to establish what characterized the material culture of the Meshchera. 12 such sites were found from the Moskva River, along the Oka River to the town Kasimov. The general opinion is nowadays, that the Oka-Ryazan culture is identical to that of the Meshchera. The graves of women have yielded objects typical of the Volga Finns, of the 4th to 7th centuries, consisting of rings, jingling pendants, buckles and torcs. A specific feature was round breast plates with a characteristic ornamentation. Some of the graves contained well-preserved copper oxides of the decorations with long black hair locked into small bells into which were woven pendants.

In the Oka River valley, the Meshchera culture appears to have disappeared by the 11th century. In the marshy north, they appear to have stayed and to have been converted into the Orthodox faith. The Meshchera nobility appears to have been converted and assimilated by the 13th century, but the common Meshchera huntsman and fisherman may have kept elements of their language and beliefs for a longer period. In the 16th century, the St Nicholas monastery was founded in Radovitsky in order to convert the remaining Meshchera pagans. The princely family Mestchersky in Russia derives its nobility from having originally been native rulers of some of these Finnic tribes.

The Meshchera language[24] is unattested, and theories on its affiliation remain speculative.[25] Some linguists think that it might have been a dialect of Mordvinic,[12] while Pauli Rahkonen has suggested on the basis of toponymic evidence that it was a Permic or closely related language.[26] Rahkonen's speculation has been criticized by other scientists, such as by the Russian Uralist Vladimir Napolskikh.[27] Nowadays, Mishar Tatar dialect is a Turkic language.

Mordvins

The Mordvins (also Mordva, Mordvinians) remain one of the larger indigenous peoples of Russia. They consist of two major subgroups, the Erzya and Moksha, besides the smaller subgroups of the Qaratay, Teryukhan and Tengushev (or Shoksha) Mordvins who have become fully Russified or Turkified during the 19th to 20th centuries. Less than one third of Mordvins live in the autonomous republic of Mordovia, Russian Federation, in the basin of the Volga River.

The Erzya Mordvins (Erzya: эрзят, Erzyat; also Erzia, Erza), who speak Erzya, and the Moksha Mordvins (Moksha: мокшет, Mokshet), who speak Moksha, are the two major groups. The Qaratay Mordvins live in Kama Tamağı District of Tatarstan, and have shifted to speaking Tatar, albeit with a large proportion of Mordvin vocabulary (substratum). The Teryukhan, living in the Nizhny Novgorod Oblast of Russia, switched to Russian in the 19th century. The Teryukhans recognize the term Mordva as pertaining to themselves, whereas the Qaratay also call themselves Muksha. The Tengushev Mordvins live in southern Mordovia and are a transitional group between Moksha and Erzya. The western Erzyans are also called Shoksha (or Shoksho). They are isolated from the bulk of the Erzyans, and their dialect/language has been influenced by the Mokshan dialects.

Muroma

The Muromians (Old East Slavic: Мурома) lived in the Oka River basin. They are mentioned in the Primary Chronicle. The old town of Murom still bears their name. The Muromians paid tribute to the Rus' princes and, like the neighbouring Merya tribe, were assimilated by the East Slavs in the 11th to 12th century as their territory was incorporated into the Kievan Rus'.[28]

The Muromian language[29] is unattested, but is assumed to have been Uralic, and has frequently been placed in the Volga-Finnic category.[12][30][31] A. K. Matveyev identified the toponymic area upon Lower Oka and Lower Klyazma, which corresponds with Muroma. According to the toponymy, the Muroma language was close to the Merya language.[32]

Permians

The Udmurts, although part of the Permians, the speakers of Permic languages, are sometimes considered to belong in the Volga Finnic group of peoples, because their homeland lies in the northern part of the Volga River basin.[33]

See also

- Baltic Finns

References

- Jaycox, Faith (2005). The Progressive Era. Infobase Publishing. p. 371. ISBN 0-8160-5159-3.

- Abercromby, John (1898) [1898]. Pre- and Proto-historic Finns. D. Nutt/Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 1-4212-5307-0.

- "Finno-Ugric religion: Geographic and cultural background » The Finno-Ugric peoples". Encyclopædia Britannica. 15th edition. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-10.

- Sinor, Denis (1990). The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia. Cambridge University Press. p. 151. ISBN 0-521-24304-1.

- Grenoble, Lenore (2003). Language Policy in the Soviet Union. Springer. pp. PA80. ISBN 978-1-4020-1298-3.

- The Uralic Language Family: Facts, Myths and Statistics; By Angela Marcantonio; p57; ISBN 0-631-23170-6

- Voegelin, C. F.; & Voegelin, F. M. (1977). Classification and index of the world's languages. New York: Elsevier. ISBN 0-444-00155-7.

- Ruhlen, Merritt (1991). A Guide to the World's Languages: Classification. Stanford University Press. p. 68. ISBN 0-8047-1894-6.

- Salminen, Tapani (2002). "Problems in the taxonomy of the Uralic languages in the light of modern comparative studies". Helsinki.fi.

- "Language Family Trees, Uralic". Ethnologue. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- "Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года". Perepis2002.ru.

- Janse, Mark; Sijmen Tol; Vincent Hendriks (2000). Language Death and Language Maintenance. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. A108. ISBN 978-90-272-4752-0.

- Petrov A., KUGARNYA, Marij kalykyn ertymgornyzho, #12 (850), 2006, March, the 24th.

- "Merya". MultiTree. 2009-06-22. Retrieved 2012-07-13.

- Wieczynski, Joseph (1976). The Modern Encyclopedia of Russian and Soviet History. Academic International Press. ISBN 978-0-87569-064-3.

- Helimski, Eugene (2006). "The «Northwestern» group of Finno-Ugric languages and its heritage in the place names and substratum vocabulary of the Russian North". In Nuorluoto, Juhani (ed.). The Slavicization of the Russian North (Slavica Helsingiensia 27) (PDF). Helsinki: Department of Slavonic and Baltic Languages and Literatures. pp. 109–127. ISBN 978-952-10-2852-6.

- Bereczki, Gábor (1996). "Le méria, une language balto-finnoise disparue". In Fernandez, M.M. Jocelyne; Raag, Raimo (eds.). Contacts de languages et de cultures dans l'aire baltique / Contacts of Languages and Cultures in the Baltic Area. Uppsala Multiethnic Papers. pp. 69–76.

- «Meryan Mastor»

- merjamaa.ru

- «National Anthem of Merya» on YouTube

- 13/07/2012+26°C. "Silent Souls (film)". Themoscownews.com. Archived from the original on 2014-03-01. Retrieved 2012-07-13.

- "Ethnofuturism and separatism"

- "Tuti questi populi, çoè nef, alich, marobab, balimata, quier, smaici, meschiera, sibir, cimano, çestan, mordua, cimarcia, sono ne la provincia de rossia"; item 2835 in: Falchetta, Piero (2006), Fra Mauro's World Map, Brepols, pp. 700–701, item 2835, ISBN 2-503-51726-9; also in the list online

- "Meshcherian". MultiTree. 2009-06-22. Retrieved 2012-07-13.

- Aikio, Ante (2012). "An essay on Saami ethnolinguistic prehistory" (PDF). Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne. Helsinki, Finland: Finno-Ugrian Society. 266: 63–117. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- Rahkonen, Pauli (2009), "The Linguistic Background of the Ancient Meshchera Tribe and Principal Areas of Settlement", Finnisch-Ugrische Forschungen, 60, ISSN 0355-1253

- "Вопросы Владимиру Напольских-2. Uralistica". Forum.molgen.org. Retrieved 2012-07-13.

- Uibopuu, Valev; Herbert, Lagman (1988). Finnougrierna och deras språk (in Swedish). Studentlitteratur. ISBN 978-91-44-25411-1.

- "Muromanian". MultiTree. 2009-06-22. Retrieved 2012-07-13.

- Wieczynski, Joseph (1976). The Modern Encyclopedia of Russian and Soviet History. Academic International Press. ISBN 978-0-87569-064-3.

- Taagepera, Rein (1999). The Finno-Ugric Republics and the Russian State. Routledge. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-415-91977-7.

- Матвеев А. К. Мерянская проблема и лингвистическое картографирование // Вопросы языкознания. 2001. № 5.

- Minahan, James (2004). The Former Soviet Union's Diverse Peoples. ABC-CLIO. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-57607-823-5.

- Klima, László (1996). The linguistic affinity of the Volgaic Finno-Ugrians and their Ethnogenesis. Oulu: Societas Historiae Fenno-Ugricae. Retrieved 2014-08-26.

- Aleksey Uvarov, "Étude sur les peuples primitifs de la Russie. Les mériens" (1875).

- Taagepera, Rein (1999). The Finno-Ugric Republics and the Russian State. Routledge. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-415-91977-7.

External links

- The Gateway to the Meshchera

- Meshchera, by Alexei Markov, senior lecturer at the University for Modern humanities

![]()