Vojislav Lukačević

Vojislav Lukačević (Serbian Cyrillic: Војислав Лукачевић; 1908 – 14 August 1945) was a Serbian Chetnik commander in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia during World War II. At the outbreak of war, he held the rank of captain of the reserves in the Royal Yugoslav Army.

Vojislav Lukačević | |

|---|---|

Vojislav Lukačević in 1944 | |

| Native name | Војислав Лукачевић |

| Nickname(s) | Voja |

| Born | 1908 Belgrade, Kingdom of Serbia |

| Died | 14 August 1945 (aged 36–37) Belgrade, Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia |

| Place of burial | Unknown |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Army |

| Years of service | –1944 |

| Rank | Major |

| Commands held | Chetnik forces in the Sandžak |

| Battles/wars |

|

When the Axis powers invaded Yugoslavia in April 1941, Lukačević became a leader of Chetniks in the Sandžak region and joined the movement of Draža Mihailović. While the Chetniks were an anti-Axis movement in their long-range goals and did engage in marginal resistance activities for limited periods, they also pursued almost throughout the war a tactical or selective collaboration with the occupation authorities against the Yugoslav Partisans. They engaged in cooperation with the Axis powers to one degree or another by establishing modi vivendi or operating as auxiliary forces under Axis control. Lukačević himself collaborated extensively with the Italians and the Germans in actions against the Yugoslav Partisans until mid-1944.

In January and February 1943, while under the overall command of Major Pavle Đurišić, Captain Lukačević and his Chetniks participated in several massacres of the Muslim population of Bosnia, Herzegovina and the Sandžak. Immediately after this, Lukačević and his Chetniks participated in one of the largest Axis anti-Partisan operations of the war, Case White, where they fought alongside Italian, German and Croatian (NDH) troops. The following November, Lukačević concluded a formal collaboration agreement with the Germans and participated in a further anti-Partisan offensive, Operation Kugelblitz.

In February 1944, Lukačević travelled to London to represent Mihailović at the wedding of King Peter of Yugoslavia. After returning to Yugoslavia in mid-1944, and in anticipation of an Allied landing on the Yugoslav coast, he decided to break with Mihailović and fight the Germans, but this was short-lived, as he was captured by the Partisans a few months later. After the war, he was tried for collaboration and war crimes and sentenced to death. He was executed in August 1945.

Early life

Lukačević was born in 1908 in Belgrade, Kingdom of Serbia to a wealthy banking family.[1] At one point, he was employed by the French civil engineering company Société de Construction des Batignolles.[2] He attained the rank of captain in the reserves of the Royal Yugoslav Army before World War II.[1]

Invasion and occupation

After the outbreak of World War II, the government of Regent Prince Paul of Yugoslavia declared its neutrality.[3] Despite this, and with the aim of securing his southern flank for the pending attack on the Soviet Union, Adolf Hitler began placing heavy pressure on the Kingdom of Yugoslavia to sign the Tripartite Pact and join the Axis. After some delay, the Yugoslav government conditionally signed the Pact on 25 March 1941. Two days later a bloodless coup d'état deposed Prince Paul and declared 17-year-old Prince Peter II of Yugoslavia of age.[4] Following the subsequent German-led invasion of Yugoslavia and the Yugoslav capitulation 11 days later, Lukačević went into hiding in the forests. He soon returned to Belgrade, where he became aware of the activities of Draža Mihailović. He then left the capital with some other officers and soldiers to form a Chetnik detachment in the Novi Pazar area of the Sandžak region.[5] On 16 November 1941 Muslim forces from Novi Pazar and Albanian forces from Kosovo attacked Raška and quickly advanced toward the town. They were commanded by Aćif Hadžiahmetović. The situation for the defenders became very difficult, so Lukačević personally engaged himself in the defence of the town.[6] On 17 November they stopped the advance of Hadžiahmetović's forces and forced them to retreat. On 21 November Lukačević took part in the attack of Chetnik forces on Novi Pazar.[7] In the summer of 1942, Lukačević and his Chetniks fought the Partisans in Herzegovina.[8]

Massacres of Muslims

In December 1942, Chetniks from Montenegro and Sandžak met at a conference in the village of Šahovići near Bijelo Polje. The conference was dominated by Montenegrin Serb Chetnik commander Major Pavle Đurišić and its resolutions expressed extremism and intolerance, as well as an agenda which focused on restoring the pre-war status quo in Yugoslavia implemented in its initial stages by a Chetnik dictatorship. It also laid claim to parts of the territory of Yugoslavia's neighbors.[9] At this conference, Mihailović was represented by his chief of staff, Major Zaharije Ostojić,[10] who had previously been encouraged by Mihailović to wage a campaign of terror against the Muslim population living along the borders of Montenegro and the Sandžak.[11]

The conference decided to destroy the Muslim villages in the Čajniče district of Bosnia. On 3 January 1943, Ostojić issued orders to "cleanse" the Čajniče district of Ustaše-Muslim organisations. According to the historian Radoje Pajović, Ostojić produced a detailed plan which avoided specifying what would be done with the Muslim population of the district. Instead, these instructions were to be given orally to the responsible commanders. Delays in the movement of Chetnik forces into Bosnia to participate in the anti-Partisan Case White offensive alongside the Italians enabled Chetnik Supreme Command to expand the planned "cleansing" operation to include the Pljevlja district in the Sandžak and the Foča district of Bosnia. A combined Chetnik force of 6,000 was assembled, divided into four detachments, each with its own commander. Lukačević commanded a force of 1,600, consisting of Chetniks from Višegrad, Priboj, Nova Varoš, Prijepolje, Pljevlja and Bijelo Polje. His force formed one of the four detachments, and Mihailović ordered that all four detachments be placed under the overall command of Đurišić.[12]

In early February 1943, during their advance northwest into Herzegovina in preparation for their involvement in Case White, the combined Chetnik force massacred large numbers of the Muslim population in the targeted areas. In a report to Mihailović dated 13 February 1943, Đurišić reported that the Chetnik forces under his command had killed about 1,200 Muslim combatants and about 8,000 old people, women, and children, and destroyed all property except for livestock, grain and hay, which they had seized.[13] Đurišić reported that:[14]

The operations were executed exactly according to orders. [...] All the commanders and units carried out their tasks satisfactorily. [...] All Muslim villages in the three above mentioned districts are entirely burnt, so that not one of the houses remained undamaged. All property has been destroyed except cattle, corn and hay. In certain places the collection of fodder and food has been ordered so that we can set up warehouses for reserved food for the units which have remained on the terrain in order to purge it and to search the wooded areas as well as establish and strengthen the organization on the liberated territory. During operations complete annihilation of the Muslim population was undertaken, regardless of sex and age.

— Pavle Đurišić

The orders for the "cleansing" operation stated that the Chetniks should kill all Muslim fighters, communists and Ustaše, but that they should not kill women and children. According to Pajović, these instructions were included to ensure there was no written evidence regarding the killing of non-combatants. On 8 February, one Chetnik commander made a notation on their copy of written orders issued by Đurišić that the detachments had received additional orders to kill all Muslims they encountered. On 10 February, Jovan Jelovac, the commander of the Pljevlja Brigade, who was subordinated to Lukačević, told one of his battalion commanders that he was to kill everyone, in accordance with the orders of their highest commanders.[15] According to the historian Professor Jozo Tomasevich, despite Chetnik claims that this and previous "cleansing actions" were countermeasures against Muslim aggressive activities, all circumstances point to it being Đurišić's partial achievement of Mihailović's previous directive to clear the Sandžak of Muslims.[13]

Case White

Lukačević and his Chetniks were drawn into closer collaboration with the Axis during the second phase of Case White,[16][17] which took place in the Neretva and Rama river valleys in late February 1943[18] and was one of the largest anti-Partisan offensives of the war.[19] Despite the fact that the Chetniks were an anti-Axis movement in their long-range goals[20] and did engage in marginal resistance activities for limited periods,[21] their involvement in Case White is one of the most significant examples of their tactical or selective collaboration with the Axis occupation forces.[20] In this instance, the participating Chetniks received Italian logistic support and included those operating as legalised auxiliary forces under Italian control.[22] During this offensive, between 12,000 and 15,000 Chetniks fought alongside Italian forces,[23] and Lukačević and his Chetniks also fought alongside German and Croatian troops against the Partisans.[24]

In February 1943, during the second phase of Case White, Lukačević and his Chetniks jointly held the town of Konjic on the Neretva river alongside Italian troops.[25] After being reinforced by German and NDH troops and some additional Chetniks, the combined force held the town against concerted attacks by the Partisans over a seven-day period.[25] The first attack was launched by two battalions of the 1st Proletarian Division on 19 February and was followed by repeated attacks by the 3rd Assault Division between 22 and 26 February.[25] Unable to capture the town and its critical bridge across the Neretva, the Partisans eventually crossed the river downstream at Jablanica.[26] Ostojić was aware of Lukačević's collaboration with the Germans and NDH troops at Konjic but, at his trial, Mihailović denied that he himself was aware of it, claiming that Ostojić controlled the communications links and kept the information from him.[27] During the fighting at Konjic, the Germans also supplied Lukačević's troops with ammunition.[28] Both Ostojić and Lukačević were highly critical of what they described as Mihailović's bold but reckless tactics during Case White, indicating that Mihailović was largely responsible for the Chetnik failure to hold the Partisans at the Neretva.[29]

In September 1943, immediately following the Italian capitulation, the Italian Venezia Division, which was garrisoned at Berane, surrendered to the British Special Operations Executive Colonel S.W. "Bill" Bailey and Major Lukačević, but Lukačević and his troops were unable to control the surrendered Italians. Partisan formations arrived in Berane shortly afterward and were able to convince the Italians to join them.[30]

Collaboration with the Germans

In September 1943, United States Lieutenant Colonel Albert B. Seitz and Lieutenant George Musulin parachuted into the Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia,[31] along with British Brigadier Charles Armstrong.[32] In November, Seitz and another American liaison officer, Captain Walter R. Mansfield, conducted a tour of inspection of Chetnik areas, including that of Lukačević. During their tour they witnessed fighting between Chetniks and Partisans. Due to their relative freedom of movement, the Americans assumed that the Chetniks controlled the territory they moved through. However, despite the praise that Seitz expressed for Lukačević, the Chetnik leader was collaborating with the Germans at the same time that he was hosting the visiting Americans.[33]

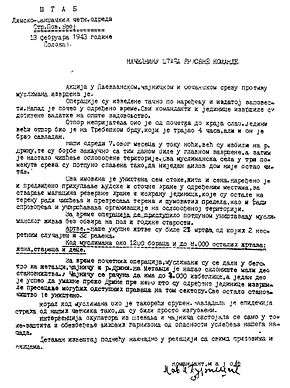

In mid-November 1943, Major Lukačević was the chief of the Chetnik detachments based near Stari Ras, near Novi Pazar in the Sandžak. On 13 November, his representative concluded a formal collaboration agreement (German: Waffenruhe-Verträge) with the representative of the German Military Commander in southeast Europe, General der Infanterie (Lieutenant General) Hans Felber.[34][35] The agreement was signed on 19 November, and covered a large portion of the Sandžak and the Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia, bounded by Bajina Bašta, the Drina river, the Tara river, Bijelo Polje, Rožaje, Kosovska Mitrovica, the Ibar river, Kraljevo, Čačak and Užice.[36] Under the agreement, a special German liaison officer was assigned to Lukačević to advise on tactics, ensure cooperation, and facilitate arms and ammunition supply.[37] British Prime Minister Winston Churchill read the decrypted text of the agreement between Lukačević and Felber, which had a significant influence on the changing attitude of the British towards Mihailović.[38]

In early December 1943, Lukačević's Chetniks participated in Operation Kugelblitz, the first of a series of German operations alongside the 1st Mountain Division, 7th SS Volunteer Mountain Division Prinz Eugen, and parts of the 187th Reserve Division, the 369th (Croatian) Infantry Division and the 24th Bulgarian Division. The Partisans avoided decisive engagement and the operation concluded on 18 December.[39] Also during December, the Higher SS and Police Leader in the Sandžak, SS-Standartenführer Karl von Krempler, posted notices authorising local Serbs to join Lukačević's Chetniks. On 22 December, shortly after the conclusion of Operation Kugelblitz, Oberst (Colonel) Josef Remold issued an order of the day commending Lukačević for his enthusiasm in fighting the Partisans in the Sandžak, and allowed him to keep some of the arms he had captured.[37]

Break with Mihailović

In mid-February 1944, Lukačević, Baćović and another officer accompanied Bailey to the coast south of Dubrovnik and were evacuated from Cavtat by a Royal Navy gunboat. Their passage through German-occupied territory was probably facilitated by Lukačević's accommodation with the Germans. At one point, Lukačević was invited to have a meal with the German garrison commander of a nearby town, but declined the offer. Lukačević and the others then travelled via Cairo to London, where Lukačević represented Mihailović at King Peter's wedding on 20 March 1944.[40] After the British government decided to withdraw support from Mihailović, Lukačević and his Chetnik companions were not allowed to return to Yugoslavia until the British mission to Mihailović headed by Armstrong had been safely evacuated from occupied territory.[41] Lukačević and the others were detained by the British in Bari and thoroughly searched by local authorities, who suspected them of a robbery that had occurred in the Yugoslav consulate in Cairo a short time before. Most of the money, jewelry and uncensored letters that they were carrying were impounded. The men were flown out of Bari on 30 May, and landed on an improvised airfield at Pranjani northwest of Čačak shortly after. Because their landing at Pranjani coincided with Armstrong's departure, Lukačević and Baćović demanded that Armstrong be held as a hostage until their impounded belongings could be returned from Bari. The Chetniks at the airfield refused to keep Armstrong any further, and he was allowed to depart without incident.[42]

In mid-1944, after Mihailović was removed from his post as Minister of the Army, Navy and Air Force as a result of the dismissal of the Purić government by King Peter,[43] Lukačević attempted to independently contact the Allies in Italy in the hope of "reaching an understanding on a common fight against the enemy".[44] When these attempts failed, Lukačević announced in August 1944 that he and other Chetnik commanders in eastern Bosnia, eastern Herzegovina and Sandžak were no longer obeying orders from Mihailović, and were forming an independent resistance movement to fight the occupiers and those collaborating with them.[45] In early September, he issued a proclamation to the people explaining his reasons for attacking the Germans.[45] On 19 October, Lukačević proposed that the Chetniks change their policy to greet the Red Army as liberators and ask to be taken under the command of a Russian general.[46] He also tried to arrange a non-aggression pact with the Partisans.[45] Subsequently, he deployed his 4,500 Chetniks into southern Herzegovina and for several days from 22 September they attacked the 369th (Croatian) Infantry Division and the Trebinje–Dubrovnik railway line, capturing some villages and taking hundreds of prisoners.[47] Mihailović formally relieved Lukačević of his command and asked other Chetnik commanders to act against him.[48] However, the Partisans, concerned Lukačević was trying to link up with a feared British landing on the Adriatic coast, attacked his forces on 25 September, first capturing his stronghold at Bileća and then comprehensively defeating him.[48] With several hundred remaining Chetniks, Lukačević withdrew as far as Foča before returning to the Bileća area in the hope of linking up with small detachments of British troops that had been landed to support Partisan operations. Instead he was captured by the Partisans.[48][49]

Trial and execution

Lukačević, along with other defendants, was tried by a military court in Belgrade between 28 July and 9 August 1945. He was accused of conducting the massacre at Foča, participating in the extermination of the Muslim population, collaboration with the occupying forces and the Serbian puppet government of General Milan Nedić and the commission of crimes against the Partisans. He was found guilty of various offences and executed by firing squad on 14 August 1945.[48]

Footnotes

- Pajović 1987, p. 107.

- Dedijer & Miletić 1990, p. 439.

- Pavlowitch 2008, p. 8.

- Pavlowitch 2008, pp. 10–13.

- Milazzo 1975, p. 15.

- Živković 2011, p. 253.

- Ćuković 1964, pp. 175, 176.

- G-2 (PB) 1944, p. 23.

- Pavlowitch 2008, p. 112.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 171.

- Milazzo 1975, p. 109.

- Pajović 1987, pp. 59–60.

- Tomasevich 1975, pp. 258–259.

- Judah 2000, pp. 120–121.

- Pajović 1987, p. 60.

- Tomasevich 1975, pp. 239–241.

- Milazzo 1975, p. 123.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 240.

- Pavlowitch 2008, p. 152.

- Milazzo 1975, p. 182.

- Milazzo 1975, pp. 103–105.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 233.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 236.

- Tomasevich 1975, pp. 231–243.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 239.

- Tomasevich 1975, pp. 239–243.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 241.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 247.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 250.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 360.

- Hehn 1971, p. 350, official name of the occupied territory.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 373.

- Tomasevich 1975, pp. 374–375.

- Tomasevich 1975, pp. 321–323.

- Roberts 1987, pp. 157 & 337.

- Tomasevich 1975, pp. 324–325.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 331.

- Pavlowitch 2008, p. 198.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 398.

- Roberts 1987, pp. 156–157, 207 & 342.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 309.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 370.

- Tomasevich 1975, pp. 369 & 425.

- Tomasevich 1975, pp. 425–426.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 426.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 395.

- Tomasevich 1975, pp. 426–427.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 427.

- Pavlowitch 2008, p. 232.

References

Books

- Ćuković, Mirko (1964). Sandžak. Nolit-Prosveta.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dedijer, Vladimir; Miletić, Antun (1990). Genocid nad Muslimanima, 1941–1945 (in Serbo-Croatian). Sarajevo: Svjetlost. ISBN 978-8-60101-525-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Judah, Tim (2000). The Serbs: History, Myth and the Destruction of Yugoslavia (2nd ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08507-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Milazzo, Matteo J. (1975). The Chetnik Movement & the Yugoslav Resistance. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-1589-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pajović, Radoje (1987). Pavle Đurišić (in Serbo-Croatian). Zagreb: Centar za informacije i publicitet.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2008). Hitler's New Disorder: The Second World War in Yugoslavia. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-1-85065-895-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Roberts, Walter R. (1987). Tito, Mihailović and the Allies: 1941–1945 (3rd ed.). New Brunswick, NJ: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-0773-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tomasevich, Jozo (1975). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: The Chetniks. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0857-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Journals

- Hehn, Paul N. (1971). "Serbia, Croatia and Germany 1941–1945: Civil War and Revolution in the Balkans". Canadian Slavonic Papers. University of Alberta. 13 (4): 344–373. JSTOR 40866373.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Živković, Milutin (2011). "Dešavanja u Sandžaku od julskog ustanka do kraja 1941 godine" (PDF). Baština (in Serbian). Priština, Leposavić: Institute for Serbian Culture. 31. Retrieved 12 June 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Documents

- G-2 (PB) (1944). "The Četniks: A Survey of Četnik Activity in Yugoslavia, April 1941 – July 1944". Caserta, Italy: Allied Forces Headquarters. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)