Sandžak Muslim militia

The Sandžak Muslim militia[a] was established in Sandžak and eastern Herzegovina in Axis occupied Yugoslavia between April or June and August 1941 during World War II. It was under control of the Independent State of Croatia until September 1941, when Italian forces gradually put it under their command and established additional units not only in Sandžak, but in eastern Herzegovina as well. After the capitulation of Italy in September 1943 it was put under German control, while some of its units were merged with three battalions of Albanian collaborationist troops to establish the "SS Polizei-Selbstschutz-Regiment Sandschak" under command of the senior Waffen SS officer Karl von Krempler.

| Sandžak Muslim militia | |

|---|---|

| Active | April or June 1941–1945 |

| Allegiance |

|

| Branch | Infantry |

| Type | Militia |

| Size | 8,000–12,000 (April 1943)

|

| Engagements | World War II in Yugoslavia

|

| Commanders | |

| Brodarevo detachment | Husein Rovčanin[2] |

| Hisardžik detachment | Sulejman Pačariz |

| Pljevlja detachment | Mustafa Zuković[3] |

| Sjenica detachment | Hasan Zvizdić |

| Bijelo Polje detachment | Ćazim Sijarić, Galjan Lukač |

| Petnjica detachment | Osman Rastoder[4] |

| Insignia | |

| Identification symbol | |

The Sandžak Muslim militia had around 2,000 men in standing forces and additional auxiliary forces on local level. Its notable commanders include Hasan Zvizdić, Husein Rovčanin, Sulejman Pačariz, Ćazim Sijarić, Selim Juković, Biko Drešević, Ćamil Hasanagić and Galjan Lukač.[6][7]

It was one of three armed groups, besides the Chetniks and Yugoslav Partisans, that operated in Sandžak during the Second World War and engaged in violent internecine fight.[8] Moslem militia participated in the suppression of the Uprising in Montenegro, committing numerous crimes against Serbs of Montenegro.[9] After the suppression of the uprising this militia continued to fight against Yugoslav Partisans, but some of its units also carried on with attacks on Serbs in Sandžak and eastern Herzegovina. According to German and Croatian sources, the size of Muslim militia in April 1943 was between 8,000 and 12,000 men.[10]

Background

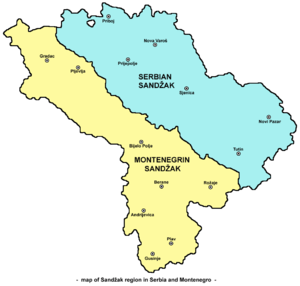

The Sandžak is a mountainous region that lies along the border between modern-day Serbia and Montenegro. A significant Muslim minority has formed part of the population of the region since the Ottoman Empire annexation of the Serbian Despotate in 1459. A history of hatred, frequent harassment and occasional violence directed towards the Sandžak Muslims by their Serb neighbors meant that they had generally maintained a system of mutual protection to keep watch over their communities and property.[11] Prior to the Congress of Berlin in 1878, the Sandžak had been joined to Bosnia and Herzegovina under Ottoman rule.[12]

Between 1929 and 1941, the Sandžak had been part of the Zeta Banovina (province) of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, whose boundaries, like those of five of the other eight banovina, were gerrymandered to ensure a Serb majority which would protect the interests of the Serbian ruling elite of Yugoslavia.[13] In the 1931 census, the counties of Bijelo Polje, Deževa, Mileševa, Nova Varos, Pljevlja, Priboj, Sjenica, and Štavica had a combined population of 204,068, with 43 per cent (87,939) being Sandžak Muslims with a small number of Albanians, and 56.5 per cent (115,260) being Orthodox Serbs or Montenegrins.[14]

Initial reactions to the invasion

In April 1941, Germany and its Axis allies invaded and occupied Yugoslavia.[15] German troops from the 8th and 11th Panzer Divisions entered the Sandžak on 16 April, and had occupied the whole region by 19 April. In all cases the county officials and gendarmes surrendered peacefully, but there were no demonstrations of support for the Germans until they arrived in each community.[16] In Sjenica, Nova Varos, Priboj, Prijepolje and Bijelo Polje the streets were deserted when the Germans arrived, with shops closed and most people staying inside their homes.[17]

In Novi Pazar parts of the community prepared a welcome for the Germans when they became aware of their approach from Raška. When the Germans arrived in town on 17 April, German flags bearing the swastika were being flown, and the troops were met by a welcoming committee who greeted them with a short speech. The welcoming committee included the inter-war mayor of the town, Aćif Hadžiahmetović, as well as Stjepan Fišer, Ahmet Daca, and Ejup Ljajić.[18] In Pljevlja some elements of the community, including the county and municipal mayors, met the Germans at the outskirts of the town and held a reception to welcome them.[19]

In Prijepolje, a meeting of prominent Serb and Muslim men was called before the Germans arrived, and during which the Serb Sreten Vukosavljević urged Serbs and Muslims to maintain good relations and treat the occupation as temporary. Only the mayor met the Germans when they arrived in town. The Germans withdrew to Pljevlja for a few days, and patrols each consisting of one Serb and one Muslim maintained law and order.[20]

On 19 April, the Germans called a meeting of Muslim notables from Novi Pazar, Sjenica, and Tutin. The meeting was held the following day in Kosovska Mitrovica, and also included representatives of the Muslim and Albanian communities of Kosovska Mitrovica, Vučitrn, Podujevo, Pristina, Peć, Istok and Drenica. The 60 delegates at the meeting were addressed by the commander of the German 60th Infantry Division Generalleutnant Friedrich-Georg Eberhardt, who told the assembly that the Germans had liberated the Albanians from the Serbs, and that he was now inviting the Albanians to take over the administration of the Kosovo region. He also said that during his division's advance from Skopje (the capital of modern-day Macedonia) to Kosovska Mitrovica they had seen that the Serb Chetniks had killed 3,000 Albanians. He stated that the Kosovo region would be part of the German-occupied territory of Serbia, under a German-dominated government in Belgrade. This statement was received in stony silence. Eberhardt then told the group that all Serbs in the Kosovo area would eventually be resettled in Serbia, and Kosovo would then contain only Albanians, Muslims and Catholics. The meeting then discussed the situation, and decided that the former Yugoslav structures and authorities in the region would be disarmed and dismantled, and that all Serb officials would be dismissed.[21]

As soon as the Sandžak Muslim leaders returned to their communities from the meeting in Kosovska Mitrovica, they installed members of their inner circles in the towns of Novi Pazar, Sjenica, and Tutin, including the town guard, courts, tax administration and postal services. This was then extended to Muslim villages in those districts. In Bijelo Polje and Pljevlja, the pre-war district and municipal mayors remained in place. Štavica district was transferred to Italian-controlled Albania.[22]

After a few days, rumours surfaced in Prijepolje that Serb Chetniks were approaching the town, and the Muslim population prepared to arm themselves in self-defence. An munition accident occurred at a meeting called to distribute weapons, and four were killed and more wounded. The Germans soon arrived to investigate, and were convinced by pro-German Muslims that Serbs had intentionally caused the explosion. They rounded up non-Muslims, as well as at least one Muslim communist, and lined them up against a wall. Other Muslims intervened to save them, telling the Germans the explosion was caused by negligence, not the Serbs.[20] The Germans only disarmed the Yugoslav gendarmerie in Tutin and nearby Crkvine. In all other centres they allowed the gendarmes to retain their weapons.[16]

Throughout the Sandžak, the communists successfully convinced a portion of the population not to surrender their weapons to the Germans as they had been ordered, but their efforts were opposed by pro-German elements of the community who encouraged the handing-in of arms. The Germans initially allowed officers of the defeated Yugoslav Army to return to their homes, so long as they reported regularly to the local garrison. This was intended to ensure that the officers were able to be easily located and interned.[23]

Partition of Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia was soon partitioned. Some Yugoslav territory was annexed by its Axis neighbors, Hungary, Bulgaria and Italy. The Italians also occupied Montenegro with the intention of setting up a vassal state, and the borders of this territory included most of the Sandžak. The Germans engineered and supported the creation of the Ustaše-led puppet state, the Independent State of Croatia (Croatian: Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, NDH), which roughly comprised most of the pre-war Banovina Croatia, along with rest of present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina and some adjacent territory. The Italians, Hungarians and Bulgarians occupied other parts of Yugoslavian territory.[24]

Germany did not annex any Yugoslav territory, but occupied northern parts of present-day Slovenia and stationed occupation troops in the northern half of the NDH.[25] The remaining territory, which consisted of Serbia proper, the northern part of Kosovo (around Kosovska Mitrovica), and the Banat was occupied by the Germans and placed under the administration of a German military government.[26]

The struggle over the Sandžak

German-Italian demarcation line

The demarcation line between areas of German and Italian responsibility through occupied Yugoslavia was determined at a meeting of the German and Italian foreign ministers in Vienna on 21–22 April 1941. Two days later, Adolf Hitler set the initial boundary (known as the Vienna Line) through the Sandžak along the line Priboj-Novi Pazar, with both those towns falling on the German side of the line.[27] The Germans were not quick to hand over parts of the region to the Italians, maintaining their occupation troops throughout the Sandžak, and initially only allowing the Italians to garrison Bijelo Polje. They were not confident in the ability of the Italians to secure the region, and did not want to rely on Serb collaborationists, at least initially. While they were able to establish co-operation with local Muslim authorities in Novi Pazar and Tutin, matters were not so straightforward in other towns of the region. Key German interests in the Sandžak included mineral exploitation and the important route towards Greece through the Ibar valley.[28]

NDH designs on the Sandžak

Ustaše ideologists considered the Sandžak to be an integral part of NDH,[29] and they wanted to occupy cities in Montenegro and the Sandžak, thereby establishing a common border with Bulgaria.[30]

On 29 April, a platoon of Ustaše troops arrived in Prijepolje, where they were welcomed by local Muslims. The platoon commander gave a short speech and addressed a meeting at a school, declaring that the Sandžak had been annexed to the NDH, and telling all the local officials they must swear an oath to their new country. Part of the platoon was stationed at the railway station at Uvac near Sjenica, and part was sent to Priboj.[31]

The aspirations of the Ustaše were given additional impetus by the Sandžak Muslims, who sent a letter to the Poglavnik (leader) of the NDH, Ante Pavelić on 30 April 1941. The letter, sent via Sarajevo, stated that the Sandžak was both economically and historically part of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and asked that the Sandžak be incorporated into the NDH. It also asked that Pavelić send a detachment of Ustaše militia to every district of the Sandžak, stating that such action had the full support of the Germans.[32][33] The letter was signed "on behalf of the districts of the Sandžak" without specifying which districts were represented, although of the 38 signatories, Pljevlja and Prijepolje supplied ten each, six were from Sjenica, there were five each from Priboj and Bijelo Polje, and two from Nova Varoš. There were no signatories from Novi Pazar or Tutin. During the period immediately after the invasion, there were several opposing currents among the Muslims of the Sandžak. Some wanted to join the NDH, others wanted to join the Italian protectorate of Albania, a group wanted to ally themselves with the pro-German Hadžiahmetović in Novi Pazar, and yet others wanted to work with the separatist Montenegrin "Greens". This divergence of views was reflected in a meeting at Bijelo Polje, which favoured joining the NDH, although a significant minority supported aligning themselves with Hadžiahmetović.[34] In the eastern part of the Sandžak, there were also significant numbers of Albanians, who were agitating for the enlargement of neighboring Albania to include large areas of the Sandžak.[35]

NDH gendarmerie moves in

On 3 May 1941, a battalion of the NDH gendarmerie began to deploy into the Sandžak from Sarajevo. For propaganda purposes, they wore the Muslim fez instead of their usual headgear. Over the following two days, the battalion established itself in Priboj, Prijepolje, Pljevlja and Nova Varos, with companies based at Uvac, Priboj, Prijepolje and Nova Varos. The NDH gendarmes disarmed all Serb gendarmes, and brought in several key people from Bosnia, who were appointed as district chiefs and as leaders of the Ustaše Youth organisation. On 5 May, a company arrived at Pljevlja and demanded that the Germans immediately hand over the town to them. The Germans refused as they were preparing to handover to the Italians, who were due to take over the town three days later.[36] At Nova Varos, the NDH gendarmes had a cool reception, the Ustaše district commissioner being a man brought in from Višegrad in eastern Bosnia. On 10 May, the Italians ordered the NDH gendarmes out of Pljevlja and dismantled the Ustaše administration in the town, as they were concerned about the NDH push to annex the Sandžak. By this time, combined German and NDH garrisons were in place in Priboj, Prijepolje and Nova Varos, and Bijelo Polje and Pljevlja were under strictly Italian control. The Germans controlled Sjenica, Tutin and Novi Pazar.[31]

German troop withdrawal

Before withdrawing their troops from the Sandžak to prepare for the pending invasion of the Soviet Union, the Germans wanted to quickly establish collaborationist control over the area. The NDH government saw this development as benefiting their aspiration to annex the Sandžak.[32] On 10 May, a large group of Muslims from Nova Varoš wrote to Hakija Hadžić, Ustaše commissioner for Bosnia, requesting that he establish an administration in that town, stating that while Muslims made up 70 per cent of the municipal population, the town was surrounded by Serb villages, whose populace they feared.[37]

Changes to the Vienna Line

In mid-May, the Sandžak portion of the Vienna Line was modified, with the border following the line Priboj-Nova Varoš-Sjenica-Novi Pazar, all of which fell on the north (German) side of the line.[38] On 15 May, a delegation of Muslims from the Sandžak arrived in Zagreb and handed a petition to Pavelić asking that the whole Sandžak be annexed by the NDH. They referred to themselves as "Croatian Muslims" and stated that they were seeking to avoid the partition of the Sandžak between various powers.[39] There were further changes to the Vienna Line on 21 May, when the Italians took over the communities of Rudo (in the NDH), Priboj, Nova Varoš, Sjenica and Duga Poljana,[38] but Novi Pazar remained in German hands.[40]

On 20 May, German motorised troops were withdrawn from Prijepolje, Nova Varos and Priboj and were replaced by two companies of infantry.[41] Bijelo Polje was garrisoned by a company of Italian infantry.[18] When they arrived in town, the Italians were met by a group of both Serb and Muslim "Greens". Through clumsy statements about the friendship between Italians and Montenegrins, without mentioning Muslims, the Italians offended these Muslims, who shifted their support to an alliance with the NDH.[41]

Despite the forming of a German-Italian commission in November 1941 to review the line through the Sandžak, no further changes occurred until the Italian surrender in early September 1943. Given their interests, neither the NDH government nor the Sandžak Muslims were happy with these arrangements.[42]

Pro-NDH coup in Sjenica

On 13 June, in the absence of a German garrison in Sjenica, pro-NDH Muslims overthrew the pro-Albanian administration, and wrote to Slavko Kvaternik, the NDH Minister of the Armed Forces asking that he immediately send NDH troops to garrison the town. They also sent a delegation to Prijepolje, asking the commander of the NDH garrison to send troops. He led a platoon of soldiers and a team of gendarmes who established themselves in the town, meeting with the small German garrison. In July, Duga Poljana was transferred to Deževa County, and was then controlled from Novi Pazar rather than Sjenica.[43]

Formation of armed groups

The pro-NDH and pro-Albanian factions within the Muslim population of the Sandžak began to organise armed groups, and this contributed to a deterioration in the relationship between Serbs and Muslims. Some Muslims even demanded that all the Serbs that had been settled in the region since World War I be expelled. Serbs reacted strongly to this demand, with their leaders in Pljevlja stating that any attempts at such evictions would be opposed by armed force.[44]

Establishment of the Muslim militia

As soon as Yugoslav resistance ended, the Sandžak Muslims strengthened their collective security arrangements by the gathering of volunteers armed with abandoned Royal Yugoslav Army weapons.[11] In the period between 29 April and 8 May 1941, Ustaše forces executed their order to capture Sandžak.[45] Between April[46] or June[47] and August 1941 they established Moslem Ustaše militia in the Sandžak, with strongholds in Brodarevo, Komaran, Hisardžik and parts of Novi Pazar, Štavički and Sjenica.[47]

On 15 May 1941 a group of Muslims from Pljevlja, Bijelo Polje and Prijepolje wrote to Pavelic and expressed the loyalty to NDH allegedly in the name of all Muslims of Sandjak.[48]

This way, besides German and Italian forces, Ustaše forces were established on the territory of Sandžak.[49] The Germans placed the town of Novi Pazar under the control of the Albanian nationalist Balli Kombëtar supporter Aćif Hadžiahmetović.[50]

On the territory of Sandžak there were many detachments of Moslem militia. All of them fought against Yugoslav Partisans in the all period of the existence of this militia. Moslem militia had standing forces of around 2,000 men who received salary and occasionally mobilized forces that were not paid. There were also auxiliary units organized in seven detachments on the municipality level.[51]

Uprising in Montenegro

The Sandžak Muslim militia participated in the suppression of the Uprising in Montenegro,[52] committing numerous crimes against Serbs of Montenegro and Montenegrins.[9] The militia was ordered to attack Serb and Montenegrin villages.[53] On 19 July Moslem militia participated in attack on Serb villages on the right bank of river Lim.[54] Units of Moslem militia from Sjenica and Korita opened additional front-line against insurgents after they captured Bijelo Polje on 20 July 1941.[55] On 17 August 1941, the militia killed 11 villagers in Slatina village near Brodarevo.[56] A detachment of Muslim militia from Bihor commanded by Rastoder attacked insurgents toward Berane.[57] Muslim militia from Pljevlja helped Italians to burn and plunder the insurgents' houses during the Italian reprisals after the Battle of Pljevlja.[58]

Italian administration

Because of the unstable situation in Montenegro, the Ustaše remained in Sandžak only until the beginning of September 1941.[59] When the Ustaše were forced to leave Sandžak, Muslims who were allied with them and their Moslem militia[60] were left alone, and they allied themselves with the occupying Italian forces.[61] In eastern parts of Sandžak, Muslim militia collaborated with German and Albanian forces.[62]

In autumn 1941 the Italians appointed Osman Rastoder as a commander of the Muslim militia detachment in upper Bihor with its seat in Petnjica.[4] The detachment of militia in Gostun was commanded by Selim Juković.[63]At the end of September 1941, the militia from Tutin participated in the attack on Ibarski Kolašin, predominantly populated by Serbs.[64] In Sjenica a wealthy Muslim whole-trader Hasan Zvizdić became a city governor who armed many local Muslims and organized them as militia.[65] In mid November 1941 Chetnik unit of 40 men went to Kosatica trying to disarm Muslim militia commanded by Sulejman Pačariz. Militiamen refused to surrender their arms and in subsequent struggle two of them were killed while one Chetnik was wounded. To revenge death of his two men, Muslim militia under command of Pačariz attacked part of Kosatica populated by Serbs and captured, brutally tortured and killed seven Serbs from Kosatica.[66]

Commanders of Muslim militia (including Osman Rastoder, Sulejman Pačariz, Ćazim Sijarić and Husein Rovčanin) participated in a conference in village of Godijeva,[67] and agreed to attack Serb villages near Sjenica and other parts of Sandžak.[68] On 31 March 1942, Chetnik leader Pavle Đurišić met with Rastoder and offered him a peace agreement between Muslims and Orthodox people. Rastoder refused the proposed agreement.[58]

At the beginning of February 1942 detachments of Muslim militia from Sjenica, Prijepolje, Brodarevo and Komaran, together with Chetniks under command of Pavle Đurišić and Italian forces were planned to attack Partisans who were retreating through Sandžak after their defeat in Užice. When Pačariz realized that Partisans managed to defeat Chetniks, he did not dare to attack Partisans, but decided to move his forces to Sjenica to help Zvizdić in case Partisans decide to attack the town again.[69]

When Italian forces recaptured Čajniče (modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina) in April 1942, they established a detachment of Moslem militia of about 1,500 men and supplied part of them with arms.[70] The Moslem militia in Jabuka (near Foča) was commanded by Husin-beg Cengić.[71] Moslem militia in Bijelo Polje was founded by Ćazim Sijarić, Vehbo Bučan and Galjan Lukač.[72] In April 1942 Italians established a battalion of Moslem militia in Metaljka, near Čajniče, composed of about 500 Muslims from villages near Pljevlja and Čajniče. A little later a command post of Moslem militia was established in Bukovica, near Pljevlja. It was commanded by Latif Moćević whose units attacked and killed local Serbs since the end of May 1942.[73] In Goražde and Foča, in retaliation for killings of Serbs by the Moslem militia, Chetniks killed around 5,000 Muslim men, women and children at the end of 1941 and in 1942.[74]

The Prijepolje Conference was organized on 7 and 8 September and attended by the political and religious representatives of the both Christian and Muslim population of Sandžak, including the representatives of their armed forces. They all agreed on the resolution to resolve any disputes peacefully, to allow all refugees to return to their homes and to provide them help in food and other necessities. This agreement was not respected. Chetnik headquarter continued to receive reports about Muslim attacks on Serb population.[75] In December 1942 around 3,000 Muslims attacked Serbian village Buđevo and several surrounding villages near Sjenica, burned Serb houses and killed Serb civilians.[76] According to Chetnik sources, Muslims were preparing to expel Serbs who lived on the territory at the right bank of Lim, Pljevlja, Čajniče and Foča.[77] Montenegrin Chetniks commanded by Pavle Đurišić pursued raids of revenge against Muslims in Sandžak, many being innocent villagers, with original motive to settle account with Moslem militias.[76][78][79] On 7 January 1943 unit commanded by Ćazim Sijarić distinguished itself during attack of Chetniks led by Pavle Đurišić who burned many Muslim villages near Bijelo Polje.[80] On 10 January 1943, Đurišić reported that Chetniks under his command had burned down 33 Muslim villages in Bijelo Polje, killed 400 members of the Moslem militia, and had also killed about 1,000 Muslim women and children. Chetniks had 14 killed and 26 wounded men.[81] After subsequent attack of Chetniks from Sandžak and Bosnia on Bukovica (village near Pljevlja), they fought against Moslem militia and, according to the report of Pavle Đurišić, killed around 1,200 combatants and 8,000 civilians.[82][83] In period February — June 1943 Muslim militia and Albanian forces burned almost all Serb villages in Tutin, Sjenica, Prijepolje and Novi Pazar and killed many people.[84] According to the historian, Professor Jozo Tomasevich, all the circumstances of these "cleansing actions" carried out by Chetniks against Muslims in the Sandžak were a partial implementation of the directive issued to Đurišić by Mihailović in December 1941, which had ordered the cleansing of the Muslim population from the Sandžak.[85] In July 1943 Draža Mihajlović proposed to leaders of Muslim militia to agree to cooperate with Chetniks to fight against communists. In August 1943 Chetnik representative and Muslim leaders of Deževo met in village Pilareta and agreed to cease all hostilities between armed Muslim forces and Chetniks and to cooperate to fight against Partisans. All Chetniks' units in Sandžak were ordered not to confront with Muslims.[86]

Many commanders of Muslim militia gathered their people and publicly expressed their opinion that Chetniks are better than Partisans who they considered as robbers. Political leaders of Sandžak Muslims (Aćif Hadžiahmetović) and Albanians (Xhafer Deva) agreed that Sandžak should be annexed by the Independent State of Croatia or divided between Croatia and Albania.[84]

German administration

After the capitulation of Italy in early September 1943, Chetniks attacked and captured many Italian garrisons in Sandžak. On 11 and 12 September 1943 Chetniks tried to capture Prijepolje, but German forces supported by Muslim militia forced them to retreat with heavy casualties.[87]

During the German administration of Sandžak, after the capitulation of Italy, every detachment of the Moslem militia was obliged to provide a certain number of men for German military units.[88] Commanders of Muslim militia chose the most capable young soldiers and send them to Novi Pazar to be trained by the SS troops. Some of them were sent to Eastern Front.[89] When German forces took control over Pljevlja from Italians, they armed around 400 members of Moslem militia.[90] In Sjenica the German commanded Moslem militia killed 50 Chetniks.[91] Hasan Zvizdić equipped them with new, German, uniforms, allowing them to keep fez.[92]

Following his appointment to the post of Höhere SS-und Polizeiführer Sandschak (Higher SS and Police Leader Sandžak) in September 1943, Karl von Krempler came to be known as the "Sanjak Prince" after his relatively successful formation of the "SS Polizei-Selbstschutz-Regiment Sandschak" (or Self-Defense Regiment “Sandschak”, Serbian: Легија Фон Кремплер). He went to the Sandžak in October and took over the local volunteer militia of around 5,000 anti-communist, anti-Serb Muslim men headquartered in Sjenica. This formation was sometimes thereafter called the Kampfgruppe Krempler or more derisively the "Muselmanengruppe von Krempler". This military unit was created by joining the three battalions of Albanian collaborationist troops with some units of Moslem militia.[93] As the senior Waffen SS officer Karl von Krempler appointed a token local Muslim named Hafiz Sulejman Pačariz as the formal commander of the unit, but as the key military trainer and contact person with German arms and munitions, remained effectively in control.[94] In Bijelo Polje Moslem militia had two detachments. One was commanded by Ćazim Sijarić and the other was under command of Galjan Lukač. Both of them were subordinated to Krempler.[95] In November 1943 Germans ordered Muslims and Chetniks in Sandžak to cease their hostilities and to cooperate united under the German command. On 15 November he ordered to Sijarić to establish communication with local Chetnik detachments and together with them and detachment of Muslim militia commanded by Galijan, to attack communist forces in Bijelo Polje. Sijarić followed German orders.[96] At the end of December 1943, Rovčanin was in command of the Muslim militia in the Sandžak.[97] On 3 February 1944 the units of the Muslim militia under command of Mula Jakup and also Biko Drešević, Sinan Salković and Faik Bahtijarević attacked villages around Kolašin. They were supported by Balli Kombëtar forces from Drenica.[98] At the beginning of April 1944 the Muslim militia participated in the battle against Partisans near Ivanjica, together with German, Chetnik and Nedic's forces.[99]

In September 1944 Tito proclaimed general amnesty, allowing collaborators to switch sides, and almost all older members of militia deserted.[100] On 22 September 1944 the Moslem militia surrendered Pljevlja to Partisans without resistance.[101] After being defeated by Partisans during their attack on Sjenica on 14 October, Pačariz and his Regiment left Sandžak and went to Sarajevo in November 1944 where "SS Polizei-Selbstschutz-Regiment Sandschak" was put under the command of Ustaše General Maks Luburić.[100]

Aftermath

Sulejman Pačariz was captured near Banja Luka in 1945, put on trial and found guilty for massacres of civilians. He was executed as war criminal.[102]

See also

Annotations

Footnotes

- Redžić 2002, p. 475.

- Vojnoistorijski institut 1956, p. 399.

- Islamska Zajednica 2007, p. 57.

- Bojović 1985, p. 245.

- Tucaković 1995, p. 301.

- Bojović & Šibalić 1979, p. 382.

- Geršković 1948, p. 216.

- Morrison 2009, p. 116.

- Zlatibor Conference 1971, p. 122.

- Gledović 1986, p. 80.

- Muñoz 2001, p. 283.

- Banac 1988, p. 101.

- Tomasevich 2001, pp. 26–27.

- Banac 1988, p. 100.

- Tomasevich 2001, p. 61.

- Ćuković 1964, p. 46.

- Ćuković 1964, pp. 47–48.

- Ćuković 1964, p. 47.

- Ćuković 1964, pp. 48–49.

- Ćuković 1964, p. 48.

- Ćuković 1964, pp. 58–60.

- Ćuković 1964, pp. 59–60.

- Ćuković 1964, pp. 49–50.

- Tomasevich 2001, pp. 61–64.

- Tomasevich 2001, p. 83.

- Kroener, Müller & Umbreit 2000, p. 94.

- Janjetović 2012, p. 102.

- Ćuković 1964, pp. 50–51.

- Goldstein 2008, p. 239.

- Bulajić 2006, p. 52.

- Ćuković 1964, p. 56.

- Đurović 1964, p. 14.

- Tepić 1998, p. 347.

- Ćuković 1964, pp. 52–53.

- Ćuković 1964, p. 54.

- Ćuković 1964, pp. 57–58.

- Ćuković 1964, p. 52.

- Janjetović 2012, pp. 102–103.

- Ćuković 1964, pp. 53–54.

- Mojzes 2011, p. 94.

- Ćuković 1964, p. 53.

- Janjetović 2012, p. 103.

- Ćuković 1964, pp. 70–71.

- Ćuković 1964, p. 55.

- Zlatibor Conference 1971, p. 465.

- Politika NIN 1990, p. 19.

- Gledović, Drulović & S̆alipurović 1970, p. 13.

- Knežević 1969, p. 63.

- Đurović 1964, p. 23.

- International Crisis Group & 8 April 2005, p. 5.

- Đuković 1982, p. 223.

- Kuprešanin 1982, p. 35.

- Ćuković 1964, p. 237.

- Zlatibor Conference 1971, p. 121.

- Montenegrin Institute for History 1961, p. 247.

- Đurović 1964, p. 30.

- Božović & Vavić 1991, p. 194.

- Lakić 2009, p. 371.

- Jovanović 1984, p. 35.

- Zlatibor Conference 1971, p. 123.

- Ćuković 1964, p. x.

- Gledović 1986, p. 38.

- Veruović 1969, p. 210.

- Božović & Vavić 1991, p. 440.

- Djurašinović-Kostja 1961, p. 279.

- Radaković 1981, pp. 662–663.

- Pajović 1977, p. 245.

- Redžić 2002, p. 61.

- Ćuković 1964, p. 247.

- Dedijer & Miletić 1990, p. 364.

- Islamska Zajednica 2007, p. 56.

- Ćuković 1964, p. 136.

- Vasović 2009, p. 36.

- Dedijer & Miletić 1990, p. 265.

- Vasović 2009, p. 47.

- Redžić 2002, p. 60.

- Pajović 1977, p. 57.

- Sedlar 2007, p. 163.

- Lampe 2000, p. 215.

- Fijuljanin 2010, p. 110.

- Dedijer & Miletić 1990, p. 383.

- Dedijer & Miletić 1990, p. 401.

- Hamović 1994, p. 85.

- Gledović 1986, p. 50.

- Tomasevich 1975, pp. 258–259.

- Ćuković 1964, p. 421.

- Ćuković 1964, p. 875.

- Ćuković 1964, p. 460.

- Radaković 1981, pp. 660–661.

- Đuković 1982, p. 214.

- Military History Gazette 1989, p. 343.

- Stanković 1983, p. 399.

- Glišić 1970, p. 215.

- DeZeng 1996, pp. 3–14.

- Ćuković 1964, p. 276.

- Ćuković 1964, p. 446.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 400.

- Božović & Vavić 1991, p. 388.

- Colić 1988, p. 188.

- Muñoz 2001, p. 295.

- Lakić 1963, p. 416.

- Vojnoistorijski institut 1956, p. 32.

- Pantelić 1988, Bojović & Šibalić 1979, Borković 1976, Institut za istoriju radničkog pokreta Srbije 1972

- Bojović 1985, Bojović & Šibalić 1979, Geršković 1948

References

Books

- Banac, Ivo (1988). With Stalin Against Tito: Cominformist Splits in Yugoslav Communism. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-2186-1.

- Bojović, Jovan R.; Šibalić, Mijuško (1979). Durmitorska partizanska republika: materijali sa naučnog skupa održanog u Žabljaku 24, 25 i 26, avgusta 1977. godine [The Durmitor Partisan Republic: Materials from the Scientific Conference held in Zabljak, 24, 25 and 26 August 1977] (in Serbo-Croatian). Titograd, Yugoslavia: Historical Institute of the Socialist Republic of Montenegro.

- Bojović, Jovan R. (1985). Prelomni događaji narodnooslobodilaćkog rata u Crnoj Gori 1943. godine: zbornik radova sa naućnog skupa održanog 19. i 20. XII 1983 (in Serbo-Croatian). Titograd, Yugoslavia: Historical Institute of the Socialist Republic of Montenegro.

- Borković, Milan (1976). Србија у рату и револуцији 1941-1945. Srpska književna zadruga.

- Božović, Branislav; Vavić, Milorad (1991). Surova vremena na Kosovu i Metohiji: kvislinzi i kolaboracija u drugom svetskom ratu. Institut za savremenu istoriju.

- Bulajić, Milan (2006). Jasenovac-1945-2005/06: 60/61.-godišnjica herojskog proboja zatočenika 22. aprila 1945 : dani sećanja na žrtve genocida nad jermenskim, grčkim, srpskim, jevrejskim i romskim narodima. Pešić i sinovi. ISBN 978-86-7540-069-1.

- Cohen, Lenard J.; Dragović-Soso, Jasna (2008). State Collapse in South-Eastern Europe: New Perspectives on Yugoslavia's Disintegration. Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-460-6.

- Colić, Mladenko (1988). Pregled operacija na jugoslovenskom ratištu 1941–1945. Vojnoistorijski Institut.

- Ćuković, Mirko (1964). Sandžak: Na osnovu sakupljenog i obrađenog materijala knjigu napisao Mirko Ćuković. Nolit.

- Dedijer, Vladimir; Miletić, Antun (1990). Genocid nad Muslimanima, 1941–1945. Svjetlost.

- Djurašinović-Kostja, Vojin (1961). Stazama proleterskim. Prosveta.

- Đuković, Isidor (1982). Prva šumadijska brigada. Narodna knjiga.

- Đurović, Milinko (1964). Ustanak naroda Jugolavije, 1941: zbornik. Pišu učesnici. Vojno delo.

- Fijuljanin, Muhedin (2010). Sandžački Bošnjaci: monografija. Centar za Bošnjačke Studije. ISBN 978-86-85599-14-9.

- Geršković, Leon (1948). Dokumenti o razvoju narodne vlasti: priručnik za izučavanje istorije narodne vlasti na fakultetima, školama i kursevima [Documents about the Development of People's Power: Manual for Studying the History of the People's Government at Universities, Schools and Courses] (in Serbo-Croatian). Prosveta.

- Gledović, Bogdan; Drulović, Čedo; S̆alipurović, Vukoman (1970). Treća proleterska sandžačka brigada: zbornik sećanja. Vojnoizdavački zavod.

- Gledović, Bogdan (1986). Četvrta sandžačka NOU brigada [Fourth Sandžak Brigade NOU] (in Serbo-Croatian). Vojnoizdav. i Novin. Centar.

- Glišić, Venceslav (1970). Teror i zločini nacističke Nemačke u Srbiji 1941–1944. Rad.

- Goldstein, Ivo (2008). Hrvatska: 1918–2008 [Croatia: 1918–2008] (in Croatian). EPH.

- Hamović, Miloš (1994). Izbjeglištvo u Bosni i Hercegovini: 1941–1945. Filip Višnjić.

- Историски записи [Historical Records]. Titograd, Yugoslavia: Historical Institute of the Socialist Republic of Montenegro. 1961.

- Jovanović, Batrić (1984). Trinaesto julski ustanak. NIO "Pobjeda," OOUR Izdavačko-publicistička djelatnost.

- Knežević, Danilo (1969). Prilog u krvi: Pljevlja 1941–1945. Opštinski odbor SUBNOR.

- Kroener, Bernard R.; Müller, Rolf-Dieter; Umbreit, Hans, eds. (2000). Germany and the Second World War, Volume 5: Organization and Mobilization of the German Sphere of Power. Part I. Wartime Administration, Economy, and Manpower Resources 1939-1941. 5. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822887-5.

- Kuprešanin, Veljko (1982). Revolucionarni likovi Beograda. Istorijski arhiv grada.

- Lakić, Zoran (1963). Narodnooslobodilačka borba u Crnoj Gori, 1941–1945: hronologija događaja.

- Lakić, Zoran (2009). Istorija Pljevalja. Opština Pljevalja.

- Lampe, John R. (28 March 2000). Yugoslavia as History: Twice There Was a Country. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77401-7.

- Jovan Marjanović; Venceslav Glišić; Milan Borković, eds. (1972). NOR i revolucija u Srbiji, 1941-1945: naučni skup posvećen 30-godišnjici ustanka, održan na Zlatiboru 25-26 septembra 1971. Institut za istoriju radničkog pokreta Srbije.

- Mojzes, Paul (2011). Balkan Genocides: Holocaust and Ethnic Cleansing in the 20th Century. Plymouth: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers.

- Morrison, Kenneth (2008). Political and Religious Conflict in the Sandzak. Conflict Studies Research Centre. ISBN 978-1-905962-45-7.

- Morrison, Kenneth (2009). Montenegro: a modern history. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-710-8.

- Muñoz, Antonio J. (2001). The East Came West: Muslim, Hindu and Buddhist Volunteers in the German Armed Forces, 1941–1945. New York, New York: Axis Europa Books. ISBN 978-1-891227-39-4.

- Pajović, Radoje (1977). Pavle Đurišić (in Serbo-Croatian). Zagreb, Yugoslavia: Centar za informacije i publicitet. ISBN 978-86-7125-006-1.

- Pantelić, Ivan (1988). Руковођење народноослободилачком борбом и револуцијом у Србији 1941-1945. Belgrade: Vojnoizdavački i novinski centar.

- Radaković, Petko (1981). "Muslimanska milicija u službi okupatora". Užička Republika, Zapisi i sećanja – I (in Serbian). Užice: Muzej ustanka 1941.

- Redžić, Vučeta (2002). Građanski rat u Crnoj Gori: Dešavanja od sredine 1942. godine do sredine 1945. godine. Stupovi.

- Sedlar, Jean W. (1 September 2007). The Axis empire in southeast Europe, 1939–1945. Booklocker.com. ISBN 978-1-60145-297-9.

- Stanković, Milivoje (1983). Prvi šumadijski partizanski odred. Narodna knjiga.

- Tepić, Ibrahim (1998). Bosna i Hercegovina od najstarijih vremena do kraja Drugog svjetskog rata. Bosanski kulturni centar.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (1975). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: The Chetniks. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0857-9.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: Occupation and Collaboration. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3615-2.

- Tucaković, Šemso (1995). Srpski zločini nad Bošnjacima-muslimanima: 1941–1945. El-Kalem i OKO.

- Vasović, Milorad S. (2009). Istorija Pljevlja. Opština Pljevlja. ISBN 978-9940-512-03-3.

- Veruović, Milorad (1969). Polimska viđenja. Savez udruženja boraca narodnooslobodilačkog rata.

Journals, papers and newspapers

- DeZeng, H.L. (1996). "The Moslem Militia and Legion of the Sandjak". Axis Europa Magazine. 2/3 (9).

- Vojno-istoriski glasnik [Military History Gazette]. 1989.

- Politika NIN. Politika. 1990.

- Janjetović, Zoran (2012). "Borders of the German occupation zone in Serbia 1941–1944" (PDF). Journal of the Geographical Institute Jovan Cvijic. Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts. 62 (2): 93–115. doi:10.2298/IJGI1202093J.

- "Serbia's Sandzak: Still Forgotten" (PDF). Crisis Group Europe Report. International Crisis Group. 8 April 2005. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- "Glasnik Rijaseta Islamske zajednice u Bosni i Hercegovini" [Bulletin of the Islamic Community Library in Bosnia and Herzegovina] (in Bosnian). Islamic Community in Bosnia and Herzegovina. 2007. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "МУСЛИМАНСКА МИЛИЦИЈА У СЛУЖБИ ОКУПАТОРА" [Muslim Militia Serving the Occupier] (PDF). Zbornik dokumenata i podataka o narodnooslobodilačkom ratu jugoslovenskih naroda [Collection of Documents and Data of the National Liberation War of the Yugoslav Peoples] (in Serbo-Croatian). Belgrade, Yugoslavia: Vojnoistorijski institut. 1956. pp. 660–663.

- NOR i revolucija u Srbiji, 1941–1945: naučni skup posvećen 30-godišnjici ustanka, održan na Zlatiboru 25–26 septembra 1971 [NOR and Revolution in Serbia, 1941–1945: Scientific Conference devoted to the 30th Anniversary of the Uprising, Zlatibor 25–26 September 1971] (in Serbo-Croatian). Institut za istoriju radničkog pokreta Srbije. 1972.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Moslem Militia. |