Vladivostok

Vladivostok (Russian: Владивосто́к, IPA: [vlədʲɪvɐˈstok] (![]()

Vladivostok Владивосток | |

|---|---|

City[1] | |

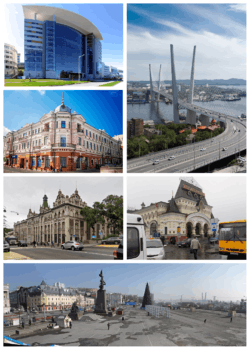

Clockwise from top: view of Vladivostok and the Golden Horn Bay, Russky Bridge, Zolotoy Bridge, Far Eastern Federal University, Square of the Fighters for Soviet Power in the Far East, GUM Department Store, Vladivostok terminus of the Trans-Siberian Railway, Arseniev State Museum, Primorye Oceanarium | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

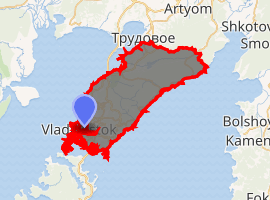

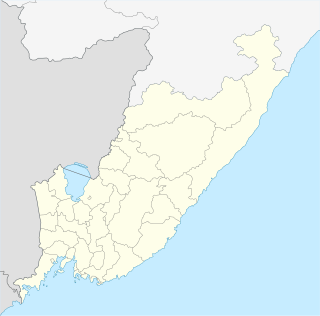

Location of Vladivostok

| |

Vladivostok Location of Vladivostok  Vladivostok Vladivostok (Primorsky Krai) | |

| Coordinates: 43°08′N 131°54′E | |

| Country | Russia |

| Federal subject | Primorsky Krai[1] |

| Founded | 2 July 1860[2] |

| City status since | 22 April 1880 |

| Government | |

| • Body | City Duma |

| • Head | Oleg Gumenyuk[3] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 331.16 km2 (127.86 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 8 m (26 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2018)[5] | 604,901 |

| • Rank | 22nd in 2010 |

| • Subordinated to | Vladivostok City Under Krai Jurisdiction[1] |

| • Capital of | Primorsky Krai[6], Vladivostok City Under Krai Jurisdiction[1] |

| • Urban okrug | Vladivostoksky Urban Okrug[7] |

| • Capital of | Vladivostoksky Urban Okrug[7] |

| Time zone | UTC+10 (MSK+7 |

| Postal code(s)[9] | 690xxx |

| Dialing code(s) | +7 423[10] |

| OKTMO ID | 05701000001 |

| City Day | First Sunday of July |

| Website | www |

Names and etymology

Vladivostok was first named in 1859 along with other features in the Peter the Great Gulf area by Nikolay Muravyov-Amursky. The name was first applied to the bay but, following an expedition by Alexey Shefner in 1860, was later applied to the new settlement.[14]

In Chinese, the city is in a place known since the Qing dynasty as Haishenwai (海參崴, Hǎishēnwǎi), from the Manchu Haišenwai (Manchu: ᡥᠠᡳᡧᡝᠨᠸᡝᡳ; Möllendorff: Haišenwai; Abkai: Haixenwai) or "small seaside village".[15]

In China, Vladivostok is now officially known by the transliteration 符拉迪沃斯托克 (Fúlādíwòsītuōkè), although the historical Chinese name 海参崴 (Hǎishēnwǎi) is still often used in common parlance and outside Mainland China to refer to the city.[16][17] According to the provisions of the Chinese government, all maps published in China have to bracket the city's Chinese name.[18]

The modern-day Japanese name of the city is transliterated as Urajiosutoku (ウラジオストク). Historically, the city was written in Kanji as 浦塩斯徳 and shortened to Urajio ウラジオ; 浦塩.[19]

History

The aboriginals of the territory on which modern Vladivostok is located are the Tungusic-speaking Udege minority, and a sub-minority called the Taz which emerged in the 1890s through members of the indigenous Udege mixing with the nearby Chinese and Hezhe. The region had been at least nominally part of many states, such as the Mohe, Balhae Kingdom, Liao Dynasty, Jīn Dynasty, Yuan Dynasty, Ming Dynasty, Qing Dynasty and various other East Asian dynasties, before Russia annexed Primorsky Krai and the island of Sakhalin by the Treaty of Beijing (1860). Qing China, which had just lost the Opium War with Britain, was unable to defend the region. The Manchu emperors of China, the Qing Dynasty, had banned Han Chinese from most of Manchuria including the Vladivostok area (see Willow Palisade)—it was only visited by illegal gatherers of ginseng and sea cucumbers.

On 20 June 1860 (2 July for Gregorian style), the military supply ship Manchur, under the command of Captain-Lieutenant Alexey K. Shefner, called at the Golden Horn Bay to found an outpost called Vladivostok. Warrant officer Nikolay Komarov, with 28 soldiers and two non-commissioned officers under his command, were brought from Nikolayevsk-on-Amur by ship to construct the first buildings of the future city.

The Manza War in 1868 was the first attempt by Russia to expel the Chinese inhabitants from territory it controlled. Hostilities broke out around Vladivostok when the Russians tried to shut off gold mining operations and expel Chinese workers there.[20] The Chinese resisted a Russian attempt to take Askold Island and in response, two Russian military stations and three Russian towns were attacked by the remaining Chinese.[21]

An elaborate system of fortifications was erected between the early 1870s and the late 1890s. A telegraph line from Vladivostok to Shanghai and Nagasaki was opened in 1871. That same year a commercial port was relocated to Vladivostok from Nikolayevsk-on-Amur. Town status was granted on 22 April 1880. A coat of arms, representing the Siberian tiger, was adopted in March 1883.

The first high school was opened in 1899. The city's economy was given a boost in 1916, with the completion of the Trans-Siberian Railway, which connected Vladivostok to Moscow and Europe.[22]

After the October Revolution, the Bolsheviks took control of Vladivostok and all the Trans-Siberian Railway. During the Russian Civil War, from May 1918,[23] they lost control of the city to the White-allied Czechoslovak Legion,[24] who declared the city to be an Allied protectorate. Vladivostok became the staging point for the Allies' Siberian intervention, a multi-national force including Japan, the United States, and China; China sent forces to protect the local Chinese community after appeals from Chinese merchants.[25] The intervention ended in the wake of the collapse of the White Army and regime in 1919; all Allied forces except the Japanese withdrew by the end of 1920.

In April 1920, the city came under the formal governance of the Far Eastern Republic, a Soviet-backed buffer state between the Soviets and Japan. Vladivostok then became the capital of the Japanese-backed Provisional Priamurye Government, created after a White Army coup in the city in May 1921. The withdrawal of Japanese forces in October 1922 spelt the end of the enclave, with the Red Army under Ieronim Uborevich taking the city on 25 October 1922.

As the main naval base of the Soviet Pacific Fleet, Vladivostok was officially closed to foreigners during the Soviet years. The city hosted the summit at which Leonid Brezhnev and Gerald Ford conducted the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks in 1974. At the time, the two countries decided quantitative limits on nuclear weapons systems and banned the construction of new land-based ICBM launchers.

In 2012, Vladivostok hosted the 24th APEC summit. Leaders from the APEC member countries met at Russky Island, off the coast of Vladivostok.[26] With the summit on Russky Island, the government and private businesses inaugurated resorts, dinner and entertainment facilities, in addition to the renovation and upgrading of Vladivostok International Airport.[27] Two giant cable-stayed bridges were built in preparation for the summit, the Zolotoy Rog bridge over the Zolotoy Rog Bay in the center of the city, and the Russky Island Bridge from the mainland to Russky Island (the longest cable-stayed bridge in the world). The new campus of Far Eastern Federal University was completed on Russky Island in 2012.[28]

In 2020, the city celebrated its foundation. This has prompted backlash among Chinese nationalists who see it as still part of ancestral homeland dated from the Qing dynasty, however unlike China's other territorial disputes, this is totally not reported on Chinese official media.[29]

Geography

The city is located in the southern extremity of Muravyov-Amursky Peninsula, which is about 30 kilometers (19 mi) long and 12 kilometers (7.5 mi) wide.

The highest point is Mount Kholodilnik, 257 meters (843 ft). Eagle's Nest Hill is often called the highest point of the city; but, with a height of only 199 meters (653 ft), or 214 meters (702 ft) according to other sources, it is the highest point of the downtown area, but not of the whole city.

Located in the extreme southeast of Asian Russia, Vladivostok is geographically closer to Anchorage, Alaska and even Darwin, Australia than it is to the nation's capital of Moscow. Vladivostok is also closer to Honolulu, Hawaii than to the western Russian city of Sochi.

Climate

Vladivostok has a monsoon-influenced humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dwb) with warm, humid and rainy summers and cold, dry winters. Owing to the influence of the Siberian High, winters are far colder than a latitude of 43 °N should warrant given its low elevation and coastal location, with a January average of −12.3 °C (9.9 °F). Since the maritime influence is strong in summer, Vladivostok has a relatively cold annual climate for its latitude. Vladivostok's yearly mean of around 5 °C (41 °F) is some ten degrees lower than in cities on the French Riviera on a similar coastal latitude on the other side of Eurasia. Winters in particular are around 20 °C (36 °F) colder than on the mildest coastlines this far north, and are considerably colder than locations on the North American east coast at similar latitudes such as Halifax, Nova Scotia and Portland, Maine.

In winter, temperatures can drop below −20 °C (−4 °F) while mild spells of weather can raise daytime temperatures above freezing. The average monthly precipitation, mainly in the form of snow, is around 18.5 millimeters (0.73 in) from December to March. Snow is common during winter, but individual snowfalls are light, with a maximum snow depth of only 5 centimeters (2.0 in) in January. During winter, clear sunny days are common.

Summers are warm, humid and rainy, due to the East Asian monsoon. The warmest month is August, with an average temperature of +19.8 °C (67.6 °F). Vladivostok receives most of its precipitation during the summer months, and most summer days see some rainfall. Cloudy days are fairly common and because of the frequent rainfall, humidity is high, on average about 90% from June to August.

On average, Vladivostok receives 840 millimeters (33 in) per year, but the driest year was 1943, when 418 millimeters (16.5 in) of precipitation fell, and the wettest was 1974, with 1,272 millimeters (50.1 in) of precipitation. The winter months from December to March are dry, and in some years they have seen no measurable precipitation at all. Extremes range from −31.4 °C (−24.5 °F) in January 1931 to +33.6 °C (92.5 °F) in July 1939.[30]

Climate data for Vladivostok, 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1919–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 5.0 (41.0) |

9.9 (49.8) |

19.4 (66.9) |

27.7 (81.9) |

29.5 (85.1) |

31.8 (89.2) |

33.6 (92.5) |

32.6 (90.7) |

30.0 (86.0) |

23.4 (74.1) |

17.5 (63.5) |

9.4 (48.9) |

33.6 (92.5) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −8.1 (17.4) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

2.2 (36.0) |

9.9 (49.8) |

14.8 (58.6) |

17.8 (64.0) |

21.1 (70.0) |

23.2 (73.8) |

19.8 (67.6) |

12.9 (55.2) |

3.1 (37.6) |

−5.1 (22.8) |

9.0 (48.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −12.3 (9.9) |

−8.4 (16.9) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

5.1 (41.2) |

9.8 (49.6) |

13.6 (56.5) |

17.6 (63.7) |

19.8 (67.6) |

16.0 (60.8) |

8.9 (48.0) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

−9.0 (15.8) |

4.9 (40.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −15.4 (4.3) |

−11.7 (10.9) |

−4.9 (23.2) |

2.0 (35.6) |

6.7 (44.1) |

11.1 (52.0) |

15.6 (60.1) |

17.7 (63.9) |

13.1 (55.6) |

5.9 (42.6) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

−11.9 (10.6) |

2.0 (35.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −31.4 (−24.5) |

−28.9 (−20.0) |

−21.3 (−6.3) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

3.7 (38.7) |

8.7 (47.7) |

10.1 (50.2) |

1.3 (34.3) |

−9.7 (14.5) |

−20.0 (−4.0) |

−28.1 (−18.6) |

−31.4 (−24.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 14 (0.6) |

15 (0.6) |

27 (1.1) |

48 (1.9) |

81 (3.2) |

110 (4.3) |

164 (6.5) |

156 (6.1) |

117 (4.6) |

57 (2.2) |

28 (1.1) |

18 (0.7) |

833 (32.8) |

| Average rainy days | 0.3 | 0.3 | 4 | 13 | 20 | 22 | 22 | 19 | 14 | 12 | 5 | 1 | 133 |

| Average snowy days | 7 | 8 | 11 | 4 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 9 | 47 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 58 | 57 | 60 | 67 | 76 | 87 | 92 | 87 | 77 | 65 | 60 | 60 | 71 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 178 | 184 | 216 | 192 | 199 | 130 | 122 | 149 | 197 | 205 | 168 | 156 | 2,096 |

| Source 1: Погода и Климат[31] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (sun, 1961–1990)[32] | |||||||||||||

| Sea temperature data for Vladivostok | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °C (°F) | -1.2 (29.8) |

-1.6 (29.1) |

-0.9 (30.4) |

2.6 (36.7) |

8.8 (47.8) |

14.2 (57.6) |

19.4 (66.9) |

22.4 (72.3) |

19.4 (66.9) |

13.7 (56.7) |

6.2 (43.2) |

0.7 (33.3) |

8.64 (47.6) |

| Source: [33] | |||||||||||||

Politics

Head of the city of Vladivostok on the principles of unity of command directs the administration of the city of Vladivostok in accordance with federal laws, the laws of the Primorsky Krai, and the charter of the city. The structure of the city administration has the City Council at the top.

The responsibilities of the administration of Vladivostok are:

- Exercise of the powers to address local issues of Vladivostok in accordance with federal laws, normative legal acts of the Duma of Vladivostok, decrees and orders of the head of the city of Vladivostok;

- The development and organization of the concepts, plans and programs for the development of the city, approved by the Duma of Vladivostok;

- Development of the draft budget of the city;

- Ensuring implementation of the budget;

- Control the use of territory and infrastructure of the city;

- Possession, use and disposal of municipal property in the manner specified by decision of the Duma of Vladivostok;

- Other authority in accordance with Article 6 of the Charter, as well as powers delegated by federal law, the laws of the jurisdiction of Primorsky Krai executive and administrative body of the local government of city district.

Legislative authority is vested in the City Council. The new City Council began operations in 2001 and on 21 June, deputies of the Duma of the first convocation of Vladivostok began their work. On 17 December 2007, the Duma of the third convocation began. The deputies consist of 35 elected members, including 18 members chosen by a single constituency, and 17 deputies from single-mandate constituencies.

Administrative and municipal status

Vladivostok is the administrative centre of the krai. Within the framework of administrative divisions, it is, together with five rural localities, incorporated as Vladivostok City Under Krai Jurisdiction—an administrative unit with the status equal to that of the districts.[1] As a municipal division, Vladivostok City Under Krai Jurisdiction is incorporated as Vladivostoksky Urban Okrug.[7]

Demographics

_1.jpg)

.jpg)

The population of the city, according to the 2010 Census, is 592,034,[34] down from 594,701 recorded in the 2002 Census.[13] This is further down from 633,838 recorded in the 1989 Census.[35] Following the 2009 recession the population of the city has continuously increased to 606,653 as of 2016[36] Ethnic Russians make up the majority of the population.

Economy

The city's main industries are shipping, commercial fishing, and the naval base. Fishing accounts for almost four-fifths of Vladivostok's commercial production. Other food production totals 11%.

A very important employer and a major source of revenue for the city's inhabitants is the import of Japanese cars.[37] Besides salesmen, the industry employs repairmen, fitters, import clerks as well as shipping and railway companies.[38] The Vladivostok dealers sell 250,000 cars a year, with 200,000 going to other parts of Russia.[38] Every third worker in the Primorsky Krai has some relation to the automobile import business. In recent years, the Russian government has made attempts to improve the country's own car industry. This has included raising tariffs for imported cars, which has put the car import business in Vladivostok in difficulties. To compensate, Prime Minister Vladimir Putin ordered the car manufacturing company Sollers to move one of its factories from Moscow to Vladivostok. The move was completed in 2009, and the factory now employs about 700 locals. It is planned to produce 13,200 cars in Vladivostok in 2010.[37]

Transportation

The Trans-Siberian Railway was built to connect European Russia with Vladivostok, Russia's most important Pacific Ocean port. Finished in 1905, the rail line ran from Moscow to Vladivostok via several of Russia's main cities. Part of the railroad, known as the Chinese Eastern Line, crossed over into China, passing through Harbin, a major city in Manchuria. Today, Vladivostok serves as the main starting point for the Trans-Siberian portion of the Eurasian Land Bridge.

Vladivostok is the main air hub in the Russian Far East. Vladivostok International Airport (VVO) is the home base of Aurora airline - a Russian Far East air carrier, a subsidiary of Aeroflot. The airline was formed by Aeroflot in 2013 by amalgamating SAT Airlines and Vladivostok Avia. The Vladivostok International Airport was significantly upgraded in 2013 with a new 3500-metre runway capable of accommodating all aircraft types without any restrictions. The Terminal A was built in 2012 with a capacity of 3.5 million passengers per year.

International flights connect Vladivostok with Japan, China, Philippines, North Korea and Vietnam.

It is possible to get to Vladivostok from several of the larger cities in Russia. Regular flights to Seattle, Washington, were available in the 1990s but have been cancelled since. Vladivostok Air was flying to Anchorage, Alaska, from July 2008 to 2013, before its transformation into Aurora airline.

Vladivostok is the starting point of Ussuri Highway (M60) to Khabarovsk, the easternmost part of Trans-Siberian Highway that goes all the way to Moscow and Saint Petersburg via Novosibirsk. The other main highways go east to Nakhodka and south to Khasan.

Urban transportation

On 28 June 1908, Vladivostok's first tram line was started along Svetlanskaya Street, running from the railway station on Lugovaya Street. On 9 October 1912, the first wooden cars manufactured in Belgium entered service. Today, Vladivostok's means of public transportation include trolleybus, bus, tram, train, funicular, and ferryboat. The main urban traffic lines are City Centre—Vtoraya Rechka, City Centre—Pervaya Rechka—3ya Rabochaya—Balyayeva, and City Centre—Lugovaya Street.

Cars of the Vladivostok funicular

Cars of the Vladivostok funicular- Buses in Vladivostok

In 2012, Vladivostok hosted the 24th Summit of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum. In preparation for the event, the infrastructure of the city was renovated and improved. Two giant cable-stayed bridges were constructed in Vladivostok, namely the Zolotoy Rog Bridge over the Golden Horn Bay in the centre of the city, and the Russky Bridge from the mainland to Russky Island, where the summit took place. The latter bridge is the longest cable-stayed bridge in the world.

Port

The port is ice-free all year round (with the help of ice breakers), and in 2002 had a foreign trade turnover worth $275 million.[39] In 2015, a special economic zone has been settled with the free port of Vladivostok.

Education

Vladivostok is home to numerous educational institutions, including five universities:

- Far Eastern Federal University

- Maritime State University

- Far Eastern State Technical Fisheries University

- Vladivostok State University of Economics and Service

- Vladivostok State Medical University (Pacific State Medical University)

The Presidium of the Far Eastern Division of the Russian Academy of Sciences (ДВО РАН) as well as ten of its research institutes are also located in Vladivostok, as is the Pacific Research Institute of Fisheries and Oceanography (Тихоокеанский научно-исследовательский рыбохозяйственный центр or ТИНРО).

Media

Over fifty newspapers and regional editions to Moscow publications are issued in Vladivostok. The largest newspaper of the Primorsky Krai and the whole Russian Far East is Vladivostok News with a circulation of 124,000 copies at the beginning of 1996. Its founder, joint-stock company Vladivostok-News, also issues a weekly English-language newspaper Vladivostok News. The subjects of the publications issued in these newspapers vary from information about Vladivostok and Primorye, to major international events. Newspaper Zolotoy Rog (Golden Horn) gives every detail of economic news. Entertainment materials and cultural news constitute a larger part of Novosti (News) newspaper which is the most popular among Primorye's young people. Also, new online mass media about the Russian Far East for foreigners is the Far East Times. This source invites readers to take part in informational support of R.F.E. for visitors, travellers and businessmen. Vladivostok operates many online news agencies, such as NewsVL.ru, Primamedia, Primorye24 and Vesti-Primorye. From 2012 to 2017 there operates youth online magazine Vladivostok-3000.

As of 2020, there operate nineteen radio stations, including three 24-hour local stations. Radio VBC (FM 101,7 MHz, since 1993) broadcasts classic and modern rock music, oldies and music of 1980s-1990s. Radio Lemma (FM 102,7 MHz, since 1996) broadcasts news, radioshows and various Russian and European-American songs. Vladivostok FM (FM 106,4 MHz, was launched in 2008) broadcasts local news and popular music (Top 40). The State broadcasting company "Vladivostok" broadcasts local news and music programs from 7 to 9, from 12 to 14 and from 18 to 19 on weekdays on the frequency of Radio Rossii (Radio of Russia).

Culture

Theatre

Maxim Gorky Academic Theatre, named after the Russian author Maxim Gorky, was founded in 1931 and is used for drama, musical and children's theatre performances.

In September 2012, a granite statue of the actor Yul Brynner (1920–1985) was inaugurated in Yul Brynner Park, directly in front of the house where he was born at 15 Aleutskaya St.

Museums

The Arsenyev Primorye Museum (Приморский государственный объединенный музей имени В.К. Арсеньева), opened in 1890, is the main museum of the Primorsky Krai. Besides the main facility, it has three branches in Vladivostok itself (including Arsenyev's Memorial House), and five branches elsewhere in the state.[40] Among the items in the museum's collection are the famous 15th-century Yongning Temple Steles from the lower Amur.

Music

The city is home to the Vladivostok Pops Orchestra.

Russian rock band Mumiy Troll hails from Vladivostok and frequently puts on shows there. In addition, the city hosted the "VladiROCKstok" International Music Festival in September 1996. Hosted by the mayor and governor, and organized by two young American expatriates, the festival drew nearly 10,000 people and top-tier musical acts from St. Petersburg (Akvarium and DDT) and Seattle (Supersuckers, Goodness), as well as several leading local bands.

Nowadays there is another annual music festival in Vladivostok, Vladivostok Rocks International Music Festival and Conference (V-ROX). Vladivostok Rocks is a three-day open-air city festival and international conference for the music industry and contemporary cultural management. It offers the opportunity for aspiring artists and producers to gain exposure to new audiences and leading international professionals.[41]

The Russian Opera House houses the State Primorsky Opera and Ballet Theater.[42]

Parks and squares

Parks and squares in Vladivostok include Pokrovskiy Park, Minnyy Gorodok, Detskiy Razvlekatelnyy Park, Park of Sergeya Lazo, Admiralskiy Skver, Skver im. Neveskogo, Nagornyy Park, Skver im. Sukhanova, Fantaziya Park, Skver Rybatskoy Slavy, Skver im. A.I.Shchetininoy.

Pokrovskiy Park

Pokrovskiy Park was once a cemetery. Converted into a park in 1934 but was closed in 1990. Since 1990 the land the park sits on belongs to the Russian Orthodox Church. During the rebuilding of the Orthodox Church, graves were found.

Minny Gorodok

Minny Gorodok is a 91-acre (37 ha) public park. Minny Gorodok means "Mine Borough Park" in English. The park is a former military base that was founded in 1880. The military base was used for storing mines in underground storage. Converted into a park in 1985, Minny Gorodok contains several lakes, ponds, and an ice-skating rink.

Detsky Razvlekatelny Park

Detsky Razvlekatelny Park is a children's amusement park located near the centre of the city. The park contains a carousel, gaming machines, a Ferris wheel, cafés, an aquarium, cinema, and a stadium.

Admiralsky Skver

Admiralsky Skver is a landmark located near the city's centre. The Square is an open space, dominated by the Triumfalnaya Arka. South of the square sits a museum of Soviet submarine S-56.

Pollution

Local ecologists from the Ecocenter organization have claimed that much of Vladivostok's suburbs are polluted and that living in them can be classified as a health hazard. The pollution has a number of causes, according to Ecocenter geo-chemical expert Sergey Shlykov. Vladivostok has about eighty industrial sites, which may not be many compared to Russia's most industrialized areas, but those around the city are particularly environmentally unfriendly, such as shipbuilding and repairing, power stations, printing, fur farming, and mining.

In addition, Vladivostok has a particularly vulnerable geography which compounds the effect of pollution. Winds cannot clear pollution from some of the most densely populated areas around the Pervaya and Vtoraya Rechka as they sit in basins which the winds blow over. In addition, there is little snow in winter and no leaves or grass to catch the dust to make it settle down.[43]

Sports

Vladivostok is home to the football club FC Luch-Energiya Vladivostok, who plays in the Russian First Division, ice hockey club Admiral Vladivostok from the Kontinental Hockey League's Chernyshev Division, and basketball club Spartak Primorye, who plays in the Russian Basketball Super League.

Twin towns - sister cities

Vladivostok is twinned with:[44]

In 2010, arches with the names of each of Vladivostok's twin towns were placed in a park within the city.[45]

From Vladivostok ferry port next to the train station, a ferry of the DBS Cruise Ferry travels regularly to Donghae, South Korea and from there to Sakaiminato on the Japanese main island of Honshu.

Notable people

- Alexandra Biriukova (1895–1967), architect

- Alexey Volkonsky (born 1978), canoeist

- Anna Shchetinina (1908–1999), captain

- Elmar Lohk (1901–1963), architect

- Eugene Kozlovsky (born 1946), writer

- Feliks Gromov (1937–), admiral

- Igor Ansoff (1918–2002), mathematician

- Igor Kunitsyn (born 1981), tennis player

- Igor Tamm (1895–1971), physicist

- Ilya Lagutenko (born 1968), singer

- Ivan Vasiliev (born 1989), ballet dancer

- Kristina Rihanoff (born 1977), dancer

- Ksenia Kahnovich (born 1987), model

- Lev Knyazev (1924–2012), writer

- Liah Greenfeld (born 1954), academic

- Mary Losseff (1907–1972), singer, film actor

- Mikhail Koklyaev (born 1978), strongman

- Natalia Pogonina (born 1985), chess player

- Nikolay Dubinin (1907–1998), biologist

- Peter A. Boodberg (1903–1972), scholar, linguist

- Stanislav Petrov (1939–2017), soldier, averted nuclear war

- Svoy (born 1980), musician

- Swati Reddy (born 1987), Indian actress

- Victor Zotov (1908–1977), botanist

- Vitali Kravtsov (born 1999), ice hockey forward

- Vladimir Arsenyev (1872–1930), explorer

- Vladimir Ossipoff (1907–1998), architect

- Wes Hurley (born 1981), filmmaker

- Yi Dong-hwi (1873–1935), Korean communist

- Yul Brynner (1920–1985), film actor

References

Notes

- Law #161-KZ

- Энциклопедия Города России. Moscow: Большая Российская Энциклопедия. 2003. p. 72. ISBN 5-7107-7399-9.

- "Обвиняемый во взятках мэр Владивостока подал в отставку".

- "Генеральный план Владивостока". Archived from the original on July 10, 2014. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- "26. Численность постоянного населения Российской Федерации по муниципальным образованиям на 1 января 2018 года". Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- "Правительство Приморского края". Официальный сайт Правительства Приморского края.

- Law #179-KZ

- "Об исчислении времени". Официальный интернет-портал правовой информации (in Russian). June 3, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- Почта России. Информационно-вычислительный центр ОАСУ РПО. (Russian Post). Поиск объектов почтовой связи (Postal Objects Search) (in Russian)

- Ростелеком завершил перевод Владивостока на семизначную нумерацию телефонов (in Russian). July 12, 2011. Retrieved November 26, 2016.

- "Vladivostok | History, Population, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- "Город Владивосток". Города России. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

- Russian Federal State Statistics Service (May 21, 2004). "Численность населения России, субъектов Российской Федерации в составе федеральных округов, районов, городских поселений, сельских населённых пунктов – районных центров и сельских населённых пунктов с населением 3 тысячи и более человек" [Population of Russia, Its Federal Districts, Federal Subjects, Districts, Urban Localities, Rural Localities—Administrative Centers, and Rural Localities with Population of Over 3,000] (XLS). Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года [All-Russia Population Census of 2002] (in Russian).

- В. В. Постников. (V. V. Postinkov.) "К осмыслению названия 'Владивосток': историко-политические образы Тихоокеанской России." ("To the comprehension of the name "Vladivostok": historical and political images of the Pacific Russia.") Ойкумена. (Ojkumena.) Vol. 4. July 2010. p. 75. (in Russian)

- “海参崴来自满语,意为‘海边的小渔村’”:阳, 曹. "冰雪黑龙江 圣诞异国游--频道风采". 天津广播网. 天津人民广播电台交通广播. Archived from the original on September 10, 2017. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- "Владивосток все же стал Хайшенвеем". Novostivl.ru. 7 May 2010. Retrieved 20 June 2017. (in Russian)

- Kee, Kwonho (2001). 中共對韓半島外交政策: 從辯證法的角度研究 [Mainland China's foreign policy in the Korean Peninsula: a dialectical analysis] (PDF) (in Chinese). National Sun Yat-sen University. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- 公开地图内容表示若干规定 (in Chinese). Ministry of Land and Resources of the People's Republic of China. January 19, 2006.

- Narangoa 2014, p. 300.

- Joana Breidenbach (2005). Pál Nyíri, Joana Breidenbach (ed.). China inside out: contemporary Chinese nationalism and transnationalism (illustrated ed.). Central European University Press. p. 89. ISBN 963-7326-14-6. Retrieved March 18, 2012.

Probably the first clash between the Russians and Chinese occurred in 1868. It was called the Manza War, Manzovskaia voina. "Manzy" was the Russian name for the Chinese population in those years. In 1868, the local Russian government decided to close down goldfields near Vladivostok, in the Gulf of Peter the Great, where 1,000 Chinese were employed. The Chinese decided that they did not want to go back, and resisted. The first clash occurred when the Chinese were removed from Askold Island,

- Joana Breidenbach (2005). Pál Nyíri, Joana Breidenbach (ed.). China inside out: contemporary Chinese nationalism and transnationalism (illustrated ed.). Central European University Press. p. 90. ISBN 963-7326-14-6. Retrieved March 18, 2012.

in the Gulf of Peter the Great. They organized themselves and raided three Russian villages and two military posts. For the first time, this attempt to drive the Chinese out was unsuccessful.

- "The Russian train experience". Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- PRECLÍK, Vratislav. Masaryk a legie (Masaryk and legions), váz. kniha, 219 str., vydalo nakladatelství Paris Karviná, Žižkova 2379 (734 01 Karviná) ve spolupráci s Masarykovým demokratickým hnutím (Masaryk Democratic Movement, Prague), 2019, ISBN 978-80-87173-47-3, pages 38 - 50, 52 - 102, 124 - 128,140 - 148,184 - 190

- "Czech troops take Russian port of Vladivostok for Allies - 6 July 1918 - HISTORY.com". HISTORY.com. Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- Joana Breidenbach (2005). Pál Nyíri, Joana Breidenbach (ed.). China inside out: contemporary Chinese nationalism and transnationalism (illustrated ed.). Central European University Press. p. 90. ISBN 963-7326-14-6. Retrieved March 18, 2012.

Then there occurred another story which has become traumatic, this one for the Russian nationalist psyche. At the end of the year 1918, after the Russian Revolution, the Chinese merchants in the Russian Far East demanded the Chinese government to send troops for their protection, and Chinese troops were sent to Vladivostok to protect the Chinese community: about 1600 soldiers and 700 support personnel.

- Levy, Clifford J. "Crisis or Not, Russia Will Build a Bridge in the East," New York Times. 20 April 2009.

- "Putin proposes Russky Island venue for APEC-2012". Vladivostok: Vladivostok News. January 31, 2007. Archived from the original on February 15, 2009. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- Williamson, Gail M.; Christie, Juliette (September 18, 2012). "Aging Well in the 21st Century: Challenges and Opportunities". Oxford Handbooks Online: 164–170. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195187243.013.0015. ISBN 9780195187243.

- "Why Russia's Vladivostok celebration prompted a backlash in China". South China Morning Post. July 2, 2020.

- Климат Владивостока [Climate of Vladivostok]. Погода и Климат (Weather and Climate) (in Russian). Retrieved June 19, 2013.

- "Climate Vladivostok". Pogoda.ru.net. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- "VLADIVOSTOK 1961–1990". NOAA. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2011). "Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года. Том 1" [2010 All-Russian Population Census, vol. 1]. Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года [2010 All-Russia Population Census] (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service.

- "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 г. Численность наличного населения союзных и автономных республик, автономных областей и округов, краёв, областей, районов, городских поселений и сёл-райцентров" [All Union Population Census of 1989: Present Population of Union and Autonomous Republics, Autonomous Oblasts and Okrugs, Krais, Oblasts, Districts, Urban Settlements, and Villages Serving as District Administrative Centers]. Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года [All-Union Population Census of 1989] (in Russian). Институт демографии Национального исследовательского университета: Высшая школа экономики [Institute of Demography at the National Research University: Higher School of Economics]. 1989 – via Demoscope Weekly.

- "Город Владивосток". Города России.

- "Putin Is Turning Vladivostok into Russia's Pacific Capital" (PDF). Russia Analytical Digest. Institute of History, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland (82): 9–12. July 12, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 6, 2011.

- Oliphant, Roland (2010). "Ruler of the East: The City of Vladivostok Is a Mixture of Promise and Neglect". Russia Profile.

- Vladivostok Economics Archived May 12, 2013, at the Wayback Machine (Russian) retrieved 18 Sep 2012

- "Музей истории Дальнего Востока имени В.К. Арсеньева". Приморский музей имени Арсеньева. July 6, 2018. Archived from the original on January 21, 2012.

- Ryzik, Melena (August 28, 2013). "East by Far East: Vladivostok Rocks". The New York Times.

- Starrs. "Russian Opera house".

- B. V. Preobrazhensky, A. I. Burago, S. A. Shlykov. Primorye Ecology. Ecological Situation. Contamination of Sea and Water Archived August 18, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Города-побратимы". vlc.ru (in Russian). Vladivostok. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- Во Владивостоке открыт сквер городов-побратимов (In Russian). Retrieved July 19, 2016.

Sources

- Законодательное Собрание Приморского края. Закон №161-КЗ от 14 ноября 2001 г. «Об административно-территориальном устройстве Приморского края», в ред. Закона №673-КЗ от 6 октября 2015 г. «О внесении изменений в Закон Приморского края "Об административно-территориальном устройстве Приморского края"». Вступил в силу со дня официального опубликования. Опубликован: "Красное знамя Приморья", №69 (119), 29 ноября 2001 г. (Legislative Assembly of Primorsky Krai. Law #161-KZ of November 14, 2001 On the Administrative-Territorial Structure of Primorsky Krai, as amended by the Law #673-KZ of October 6, 2015 On Amending the Law of Primorsky Krai "On the Administrative-Territorial Structure of Primorsky Krai". Effective as of the official publication date.).

- Законодательное Собрание Приморского края. Закон №179-КЗ от 6 декабря 2004 г. «О Владивостокском городском округе», в ред. Закона №48-КЗ от 7 июня 2012 г. «О внесении изменений в Закон Приморского края "О Владивостокском городском округе"». Вступил в силу 1 января 2005 г.. Опубликован: "Ведомости Законодательного Собрания Приморского края", №76, 7 декабря 2004 г. (Legislative Assembly of Primorsky Krai. Law #179-KZ of December 6, 2004 On Vladivostoksky Urban Okrug, as amended by the Law #48-KZ of June 7, 2012 On Amending the Law of Primorsky Krai "On Vladivostoksky Urban Okrug". Effective as of January 1, 2005.).

- Faulstich, Edith. M. "The Siberian Sojourn" Yonkers, N.Y. (1972–1977)

- Narangoa, Li (2014). Historical Atlas of Northeast Asia, 1590-2010: Korea, Manchuria, Mongolia, Eastern Siberia. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231160704.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Poznyak, Tatyana Z. 2004. Foreign Citizens in the Cities of the Russian Far East (the second half of the 19th and 20th centuries). Vladivostok: Dalnauka, 2004. 316 p. (ISBN 5-8044-0461-X).

- Stephan, John. 1994. The Far East a History. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1994. 481 p.

- Trofimov, Vladimir et al., 1992, Old Vladivostok. Utro Rossii Vladivostok, ISBN 5-87080-004-8

External links

| Wikinews has news related to: |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Vladivostok. |

- Official website of Vladivostok (in Russian)

- Vladivostok at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Historical Map of Vladivostok (1912), Perry–Castañeda Library Map Collection, University of Texas, Austin.

- Timelapse video of Vladivostok on YouTube (in Russian)