Nikolay Muravyov-Amursky

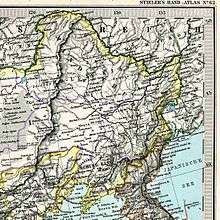

Nikolay Nikolayevich Muravyov-Amursky (also spelled as Nikolai Nikolaevich Muraviev-Amurskiy; Russian: Никола́й Никола́евич Муравьёв-Аму́рский; August 23 [O.S. August 11] 1809 – November 30 [O.S. November 18] 1881) was a Russian general, statesman and diplomat, who played a major role in the expansion of the Russian Empire into the Amur River basin and to the shores of the Sea of Japan.

Nikolay Muravyov-Amursky | |

|---|---|

Nikolay Muravyov-Amursky (1863); portrait by Konstantin Makovsky | |

| Born | August 23, 1809 St. Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Died | November 30, 1881 (aged 72) Paris, France |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Imperial Russian Army |

| Years of service | 1827–1861 |

| Rank | General of the Infantry |

| Battles/wars | Caucasian War Russo-Turkish War (1828–1829) November Uprising Crimean War |

| Awards | Order of St. George Order of St. Vladimir |

The surname Muravyov has also been transcribed as Muravyev or Murav'ev.[1]

Early life and career

Nikolay Muravyov was born in St. Petersburg. He graduated from the Page Corps in 1827. He participated in the Siege of Varna in the Russo-Turkish War in 1828–1829, and later in suppression of the November Uprising in Poland in 1831. Due to health reasons, he retired from the military in 1833 and returned home to manage his father's estate. However, he returned to active duty in 1838, as General Golovin's aide-de-camp, to serve in the Caucasus region. During one of the campaigns against the mountain people Muravyov was wounded.

In 1840, Muravyov was assigned to command one of the sections of the Black Sea coast defense lines, during which time he participated in the suppression of the Ubykh people.

Muravyov was promoted in rank to major-general in 1841, but had to permanently retire from the military due to illness. He transferred to the Ministry of Internal Affairs and was appointed as an acting military and civil governor of Tula province in 1846. Eager in his willingness to improve the province's state of affairs, he proposed to establish the governorate agricultural society. Muravyov was the first governor to propose Tsar Nicholas I to abolish serfdom; a motion signed by nine local land-owners. While the tsar did nothing about the petition, from then on he always referred to Muravyov as a "liberal" and a "democrat".

Government of East Siberia

On September 5, 1847, Muravyov was appointed the governor-general of Irkutsk and Yeniseysk (Eastern Siberia). His appointment was a subject of much controversy, as it was unusual for a person of his age (only 38 at the time) to be put in charge of such a vast territory. Contrary to the views of Karl Nesselrode, the Russian Foreign Minister, Muravyov was personally instructed by Tsar Nicholas I to press for an advantage against China.[2] Muravyov's first action as governor-general was to put end to the embezzlement of public funds. He also mandated the study of the Russian language in schools for native Siberian and Far Eastern peoples. He pursued the exploration and settlement of the territories north of the Amur River, often utilizing the help of political exiles. Many of his actions were aimed to expand commerce in the Far Eastern region. Seeing religion as a powerful form of control over the local population, he favored the building of new Christian churches and promoted local religious beliefs such as shamanism and Buddhism.

After the 1689 Treaty of Nerchinsk, Russia lost the right to navigate the Amur River. Muravyov insisted on conducting an aggressive policy with China despite strong resistance from St. Petersburg officials, who feared a breakdown in relations between the two countries. Nevertheless, because the lower reaches of the Amur River were, in fact, being claimed by the Russians, several expeditions organized by Gennady Nevelskoy had been approved by the government. In 1851–1853, several expeditions were sent to the Amur Liman and Sakhalin, with Russian settlements being established in those areas.

On January 11 1854 [O.S. December 31, 1853], Tsar Nicholas I authorized Muravyov to carry the negotiations with the Chinese regarding establishing a border along the Amur River and to transport troops to the Amur's estuary. In 1854–1858, Muravyov assisted Gennady Nevelskoy in achieving that goal. The first expedition took place in May 1854. A fleet of 77 barges and rafts, led by the steamship Argun, sailed down to the Amur's estuary. Due to the Crimean War, a portion of the fleet was then sent to Kamchatka's Avacha Bay, where a series of artillery batteries was established to defend the peninsula. The batteries played a major role in defending the city of Petropavlovsk (see Siege of Petropavlovsk), which was attacked by the English and French forces.

The 1855's expedition transported the first Russian settlers to the Amur's estuary. Muravyov started negotiations with the Chinese about that time.

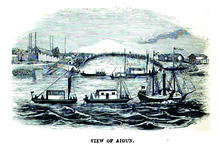

Treaty of Aigun

During the last expedition of 1858, Muravyov concluded the Treaty of Aigun with the Qing official Yishan. The Chinese were initially against setting any kinds of boundaries along the Amur River, preferring the status quo of keeping the adjacent territories under joint control of Russia and China. Muravyov, however, was able to persuade the Chinese that Russia's intentions were peaceful and constructive. The Treaty of Aigun effectively recognized the Amur River as the boundary between Russia and Qing Empire and granted Russia free access to the Pacific Ocean. For this, Muravyov was granted the title of Count Amursky (i.e., "of the Amur River"). According to an article by the Russian novelist Vladimir Barayev,[3] the signing of the treaty was celebrated by grandiose illumination in Peking and festivities in major Siberian cities.[4] The new territories acquired by Russia included Priamurye and most of the territories of modern Primorsky and Khabarovsk krais (territories).

The Treaty of Aigun was confirmed and expanded by the provisions of the Beijing Treaty of 1860, which granted Russia right to the Ussuri krai and southern parts of Primorye.

As a governor general of Eastern Siberia, Muravyov-Amursky made numerous attempts to settle the shores of the Amur River. These attempts were mostly unsuccessful as very few people wanted to move to the Amur voluntarily. Muravyov had to transfer several Baikal Cossacks detachments to populate the area. Also unsuccessful were attempts to organize steamboat transportation on the Amur and to build a postal road.

As the main objection of the St. Petersburg officials against taking over the left bank of the Amur was lack of people to defend the new territories, Muravyov-Amursky successfully petitioned to free Nerchinsk peasants from mandatory works in the ore mines. With these people, a 12,000 corps of Amur Cossacks was formed and used to settle some of the lands, the military core being the Cossacks transferred from the Transbaikalia.

Muravyov-Amursky retired from his post of governor general in 1861 after his proposal to divide Eastern Siberia into two separate governorates general was declined. He was appointed as a member of the State Council. In 1868, he moved to Paris, France, where he lived until his death in 1881, visiting Russia only occasionally to participate in the State Council meetings.

Memory

_front.jpg)

In 1891, a bronze statue of Muravyov was erected on one of the Amur River's cliffs near Khabarovsk. In 1929, it was taken off and replaced with a statue of Lenin, which stood there until 1989. The Muravyov-Amursky memorial was restored in 1993.

In 1992, the remains of Muravyov-Amursky were brought from Paris to be re-buried in the central part of Vladivostok, which stands on the Muravyov-Amursky Peninsula, named after this statesman. In 2012 a bronze statue of the governor was installed over the tomb, overlooking the Zolotoy Rog bay, which he visited in 1850s.

The Khabarovsk monument—along with the Khabarovsk Bridge over the Amur River—is depicted on the 5000 ruble banknote issued by the Central Bank of the Russian Federation on July 31, 2006.

Notes and references

- E.g., in Paine, S. C. M. (1996), Imperial rivals: China, Russia, and their disputed frontier, M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 1-56324-724-0

- Edgar Franz, Philipp Franz von Siebold and Russian Policy and Action on Opening Japan to the West in the Middle of the Nineteenth Century, Munich: Iudicum 2005

- Владимир Бараев представляет новый роман «Гонец Чингисхана» (Vladimir Barayev presents his new novel, Ghengis Khan's messenger)

- Vladimir Barayev, "Николай Николаевич Муравьёв-Амурский" (Nikolay Nikolayevich Muravyov-Amursky). Алфавит (Alfavit) newspaper, No. 30, 2000 (in Russian)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nikolay Muravyov-Amursky. |

See also

Further reading

- Bassin, Mark. "Inventing Siberia: visions of the Russian East in the early nineteenth century." American Historical Review 96.3 (1991): 763-794. online

- Bassin, Mark. Imperial visions: nationalist imagination and geographical expansion in the Russian Far East, 1840–1865 (Cambridge University Press, 1999).

- Gibson, James R. "The Significance of Siberia to Tsarist Russia." Canadian Slavonic Papers 14.3 (1972): 442-453.

![]()

|title= (help)