Visayas

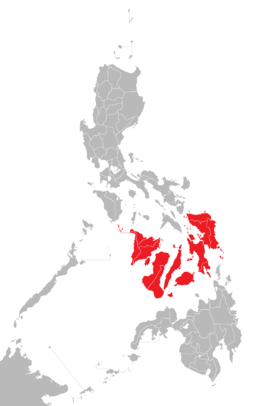

The Visayas (/vɪˈsaɪəz/ vi-SY-əz), or the Visayan Islands[2] (Cebuano: Kabisay-an, locally [kabiˈsajʔan]; Tagalog: Kabisayaan [kabiˈsɐjaʔan]), are one of the three principal geographical divisions of the Philippines, along with Luzon and Mindanao. Located in the central part of the archipelago, it consists of several islands, primarily surrounding the Visayan Sea, although the Visayas are also considered the northeast extremity of the entire Sulu Sea.[3] Its inhabitants are predominantly the Visayan peoples.

Native name:

| |

|---|---|

Location of the Visayas within the Philippines | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Southeast Asia |

| Archipelago | Philippines |

| Major islands | |

| Area | 71,503 km2 (27,607 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 2,465 m (8,087 ft) |

| Highest point | Kanlaon Volcano |

| Administration | |

| Regions | |

| Largest settlement | Cebu City (pop. 922,611) |

| Demographics | |

| Demonym |

|

| Population | 19,373,431 (2015)[1] |

| Pop. density | 292/km2 (756/sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | |

The major islands of the Visayas are Panay, Negros, Cebu, Bohol, Leyte and Samar.[6] The region may also include the provinces of Palawan, Romblon, and Masbate whose populations identify as Visayan and whose languages are more closely related to other Visayan languages than to the major languages of Luzon.

There are three administrative regions in the Visayas: Western Visayas (pop. 7.1 million), Central Visayas (6.8 million) and Eastern Visayas (4.1 million).[7] The Negros Island Region existed from 2015 to 2017, separating Negros Occidental and its capital Bacolod from Western Visayas and Negros Oriental from Central Visayas. The region has been dissolved since.

Etymology

The etymology of Visayas is unknown. The word "Bisaya" was first documented in Spanish sources in reference only to the non-Ati inhabitants of the island of Panay and possibly parts of Negros. They were described by the Spanish as being "white people" with no tattoos. In contrast, the Spaniards called the inhabitants of other Visayan islands as the Pintados ("the painted ones") in reference to their practice of tattooing their entire bodies. It is unlikely that "Bisaya" was used as a collective endonym by the closely related native Visayans prior to the Spanish arrival.

Visayans more specifically refer to themselves by their ethnic groups, like Sugbuanon, Hiligaynon, Karay-a, Waray, Bol-anon, and so on.[8] It was the Spanish who applied the term to the people of the entire Visayas within a few decades after encountering the natives of Panay, apparently based on the erroneous conclusion that the other languages were mere "dialects" of Panay Visayan and that they all belong to the same ethnic group.[8][9][10]

From the 1950s to 1960s, there were common spurious claims by various authors that "Bisaya" is derived from "Sri Vijaya", arguing that the Visayans were either settlers from Sri Vijaya or were subjects of Sri Vijaya. This claim is largely based only on the resemblance of the word "Bisaya" to "Vijaya". But as the linguist Eugene Verstraelen pointed out, "Vijaya" would evolve to become "Bidaya" or "Biraya", not "Bisaya", based on how other Sanskrit-derived loanwords become integrated into Philippine languages.[8][11][12]

Similarly there are claims that it was the name of a folk hero (allegedly "Sri Visaya") or that it originated from the exclamation "Bisai-yah!" ("how beautiful!") by the Sultan of Brunei who was visiting Visayas for the first time. However these claims have all been refuted by linguists and anthropologists as baseless.[8]

The name has also been hypothesized to be related to the Bisaya ethnic group of Borneo, the latter is incidentally recounted in the Maragtas epic as being the source of the settlers in Panay. However evidence for this is still paltry. Even the languages of the Bisaya of Borneo and the Bisaya of the Philippines do not show any special correlation, apart from both belonging to the Austronesian languages.[8]

History

After the defeat of the Magellan expedition at the Battle of Mactan by Lapu-Lapu, King Philip II of Spain sent Miguel López de Legazpi in 1543 and 1565 to colonize the islands for Spain. Subsequently, the Visayas region and many kingdoms began converting to Christianity and adopting western culture. By the 18th and 19th centuries, the effects of colonization on various ethnic groups turned sour and revolutions such as those of Francisco Dagohoy began to emerge.

Various personalities who fought against the Imperial Spanish Colonial Government arose within the archipelago. Among the notable ones are Graciano Lopez Jaena[13] and Martin Delgado from Iloilo, Aniceto Lacson, León Kilat and Diego de la Viña from Negros, Venancio Jakosalem Fernandez from Cebu,[14] and two personalities from Bohol by the name of Tamblot, who led the Tamblot Uprising in 1621 to 1622 and Francisco Dagohoy, the leader of the Bohol Rebellion that lasted from 1744 to 1829.[15] Negros briefly stood as an independent nation in the Visayas in the form of the Cantonal Republic of Negros, before it was absorbed back to the Philippines because of the American takeover of the archipelago.[16]

On 23 May 2005, Palawan (including its highly urbanized capital city of Puerto Princesa) was transferred from Mimaropa (Region IV-B) to Western Visayas (Region VI) under Executive Order No. 429, signed by Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, who was the president at that year.[17] However, Palaweños criticized the move, citing a lack of consultation, with most residents in Puerto Princesa and all Palawan municipalities but one, preferring to stay in Mimaropa (Region IV-B). Consequently, Administrative Order No. 129 was issued on 19 August 2005 that the implementation of E.O. 429 be held in abeyance, pending approval by the president of its Implementation Plan.[18] The Philippine Commission on Elections reported the 2010 Philippine general election results for Palawan as a part of the Region IV-B results.[19] As of 30 June 2011, the abeyance was still in effect, with Palawan and its capital city remaining under Mimaropa (Region IV-B).

On 29 May 2015, the twin provinces of Negros Occidental (including its highly urbanized capital city of Bacolod) and Negros Oriental were joined together to form the Negros Island Region under Executive Order No. 183, signed by President Benigno Aquino III. It separated both, the former province and its capital city from Western Visayas and the latter province from Central Visayas.

On 9 August 2017, President Rodrigo Duterte signed Executive Order No. 38, revoking the Executive Order No. 183 signed by (former) President Benigno Aquino III on 29 May 2015, due to the reason of the lack of funds to fully establish the NIR according to Benjamin Diokno, the Secretary of Budget and Management.

Mythical allusions and hypotheses

Historical documents written in 1907 by Visayan historian Pedro Alcántara Monteclaro in his book Maragtas tell the story of the ten leaders (Datus) who escaped from the tyranny of Rajah Makatunaw from Borneo and came to the islands of Panay. The chiefs and followers were said to be the ancestors (from the collapsing empires of Srivijaya and Majapahit) of the Visayan people. The documents were accepted by Filipino historians and found their way into the history of the Philippines. As a result, the arrival of Bornean tribal groups in the Visayas is celebrated in the festivals of the Ati-Atihan in Kalibo, Aklan and Binirayan in San Jose de Buenavista, Antique. Foreign historians such as William Henry Scott maintains that the book contains a Visayan folk tradition.[20]

A contemporary theory based on a study of genetic markers in present-day populations is that Austronesian peoples from Taiwan populated the larger island of Luzon and headed south to the Visayas and Mindanao, and then to Indonesia and Malaysia, then to Pacific Islands and finally to the island of Madagascar, at the west of the Indian Ocean.[21] The study, though, may not explain inter-island migrations, which are also possible, such as Filipinos migrating to any other Philippine provinces.

Administrative divisions

Administratively, the Visayas is divided into 3 regions, namely Western Visayas, Central Visayas and Eastern Visayas. Each region is headed by a Regional Director who is elected from a pool of governors from the different provinces in each region.

The Visayas is composed of 16 provinces, each headed by a Governor. A governor is elected by popular vote and can serve a maximum of three terms consisting of three years each.

Western Visayas (Region VI)

Western Visayas consists of the islands of Panay and Guimaras and the western half of Negros. The regional center is Iloilo City. Its provinces are:

- Aklan

- Antique

- Capiz

- Guimaras

- Iloilo

- Negros Occidental

Central Visayas (Region VII)

Central Visayas includes the islands of Cebu, Siquijor and Bohol and the eastern half of Negros. The regional center is Cebu City. Its provinces are:

Eastern Visayas (Region VIII)

Eastern Visayas consists of the islands of Leyte, Samar and Biliran. The regional center is Tacloban City. Its provinces are:

Scholars have argued that the region of Mimaropa and the province of Masbate are all part of the Visayas in line with the non-centric view. This is contested by a few politicians in line with the Manila-centric view.[22][23]

Major cities and municipalities

Below is a list of cities and major towns in the Visayas by population.

Language

Languages spoken at home are primarily Visayan languages despite the usual misconception that these are dialects of a single macrolanguage. Major languages include Hiligaynon or Ilonggo in much of Western Visayas, Cebuano in Central Visayas, and Waray in Eastern Visayas. Other dominant languages are Aklanon, Kinaray-a, and Capiznon. Filipino, the 'national language' based on Tagalog, is widely understood but seldom used. English, another official language, is more widely known and is preferred as the second language most especially among urbanized Visayans. For instance, English rather than Tagalog is frequently used in schools, public signs and mass media.

Cebuano vs. Bisaya

Although the word Bisaya has been adapted into the Cebuano terminology for centuries, it should never be equated with the word Cebuano. Even if its origin still has a lot of issues up to the present time, the word Bisaya is commonly used to refer to the inhabitants living in the Visayas region. It is therefore not accurate to exclusively identify Bisaya with Cebuano because that precludes all the other inhabitants of the region. All Cebuanos can be called Bisaya, but not all Bisaya can be called Cebuanos. Furthermore, Bisaya should not be referred to as a language and should never be equated with the Cebuano language, although majority of the Visayan inhabitants speak the Cebuano language. The most commonly used Cebuano term to have a reference to the Visayan group of languages is "Binisaya." It is an adjective that is used to describe also anything that pertains to being Visayan. For example: "binisaya'ng awit" which is translated into English as, "Visayan song."

Notes

- Census of Population (2015). Highlights of the Philippine Population 2015 Census of Population. PSA. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- "Visayan Islands" Merriam-Webster Dictionary. http://www.merriam-webster.com/concise/visayan%20islands

- C.Michael Hogan. 2011. Sulu Sea. Encyclopedia of Earth. Eds. P.Saundry & C.J.Cleveland. Washington DC

- "Executive Order No. 429". President of the Philippines. Archived from the original on 2007-07-07. Retrieved 2009-05-18.

- "Administrative Order No. 129". President of the Philippines. Archived from the original on 2009-07-13. Retrieved 2009-05-18.

- On May 23, 2005, Palawan and Puerto Princesa City were moved to Western Visayas by Executive Order No. 429.[4] However, on August 19, 2005, President Arroyo issued Administrative Order No. 129 to hold the earlier E.O. 429 in abeyance pending a review.[5] As of 2010, Palawan and the highly urbanized city of Puerto Princesa still remain a part of the Mimaropa region.

- "PSA Makati ActiveStats - PSGC Interactive - List of Regions". Philippine Statistics Authority. June 30, 2015. Archived from the original on October 13, 2008. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

- Baumgartner, Joseph (1974). "The Bisaya of Borneo and the Philippines: A New Look at Maragtas". Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society. 2 (3): 167–170. JSTOR 29791138.

- Zorc, David Paul. The Bisayan Dialects of the Philippines: Subgrouping and Reconstruction. Canberra, Australia: Dept. of Linguistics, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University, 1977.

- Cf. Maria Fuentes Gutierez, Las lenguas de Filipinas en la obra de Lorenzo Hervas y Panduro (1735-1809) in Historia cultural de la lengua española en Filipinas: ayer y hoy, Isaac Donoso Jimenez,ed., Madrid: 2012, Editorial Verbum, pp. 163-164.

- Verstraelen, Eugene; Trosdal, Mimi (1974). "Lexical Studies on the Cebuano Language". Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society. 2 (4): 231–237. JSTOR 29791163.

- Verstraelen, Eugene (1973). "Linguistics and Philippine Prehistory". Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society. 1 (3): 167–174. JSTOR 29791077.

- Dr. Robert L. Yoder, FAPC."Graciano López Jaena". Universitat Wien. Retrieved 2013-07-26.

- "Venancio's Leon Kilat". Inquirer.net. Retrieved 2013-07-26.

- "The Dagohoy Rebellion". Watawat.net. Retrieved 2013-07-26.

- WorldStatesmen. "Philippines - Republic of Negros". Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- President of the Philippines (May 23, 2005). "Executive Order No. 429 s. 2005". Official Gazette. Philippine Government.

- President of the Philippines (19 August 2005). "Administrative Order No. 129 s. 2005". Official Gazette. Philippine Government.

- Philippine 2010 Election Results: Region IV-B, Philippine Commission on Elections.

- Scott 1984, pp. 81–103.

- Cristian Capelli; et al. (2001). "A Predominantly Indigenous Paternal Heritage for the Austronesian-Speaking Peoples of Insular Southeast Asia and Oceania" (PDF). American Journal of Human Genetics. 68 (2): 432–443. doi:10.1086/318205. PMC 1235276. PMID 11170891. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-11.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Nene Pimentel gives details on proposal for federalist government".

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7yRvtREhJdI

References

- Scott, William Henry (1984). Prehispanic Source Materials for the study of Philippine History. New Day Publishers. ISBN 978-971-10-0226-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)