Viroplasm

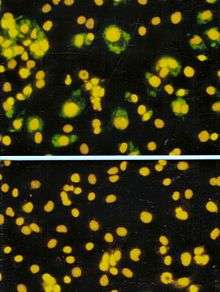

A viroplasm, sometimes called 'virus factory' or 'virus inclusion'.[1] is an inclusion body in a cell where viral replication and assembly occurs. They may be thought of as viral factories in the cell. There are many viroplasms in one infected cell, where they appear dense to electron microscopy. Very little is understood about the mechanism of viroplasm formation.

Definition

A viroplasm is a perinuclear or a cytoplasmic large compartment where viral replication and assembly occurs.[2] The viroplasm formation is caused by the interactions between the virus and the infected cell, where viral products and cell elements are confined.[2]

Groups of viruses that form viroplasms

Viroplasms have been reported in many unrelated groups of Eukaryotic viruses that replicate in cytoplasm, however, viroplasms from plant viruses have not been as studied as viroplasms from animal viruses.[2] Viroplasms have been found in the cauliflower mosaic virus,[3] rotavirus,[4] vaccinia virus[5] and the rice dwarf virus.[6] These appear electron-dense under an electron microscope and are insoluble.[2]

| Baltimore's classification | Family | Species |

| I: dsDNA viruses | Poxviridae Asfarviridae Iridoviridae Mimiviridae |

vaccinia virus[7]

African swine fever virus [8] Herpes simplex virus[2] |

| II: ssDNA viruses | ||

| III: dsRNA viruses | Reoviridae | Avian reovirus[11] |

| IV: (+)ssRNA viruses | Togaviridae Flaviviridae |

Rubella virus[12] |

| V: (−)ssRNA viruses | Rhabdoviridae | Rabies virus[13] |

| VI: ssRNA-RT viruses | Retroviridae | Human immunodeficiency virus[15] |

| VII: dsDNA-RT viruses | Caulimoviridae | Cauliflower mosaic virus [16] |

Structure and formation

Viroplasms are localized in the perinuclear area or in the cytoplasm of infected cells and are formed early in the infection cycle.[2][17] The number and the size of viroplasms depend on the virus, the virus isolate, hosts species, and the stage of the infection.[18] For example, viroplasms of mimivirus have a similar size to the nucleus of its host, the amoeba Acanthamoeba polyphaga.[9]

A virus can induce changes in composition and organization of host cell cytoskeletal and membrane compartments, depending on the step of the viral replication cycle.[1] This process involves a number of complex interactions and signaling events between viral and host cell factors.

Viroplasms are formed early during the infection; in many cases, the cellular rearrangements caused during virus infection lead to the construction of sophisticated inclusions —viroplasms— in the cell where the factory will be assembled. The viroplasm is where components such as replicase enzymes, virus genetic material, and host proteins required for replication concentrate, and thereby increase the efficiency of replication.[1] At the same time, large amounts of ribosomes, protein-synthesis components, protein folding chaperones, and mitochondria are recruited. Some of the membrane components are used for viral replication while some others will be modified to produce viral envelopes, when the viruses are enveloped. The viral replication, protein synthesis and assembly require a considerable amount of energy, provided by large clusters of mitochondria at the periphery of viroplasms. The virus factory is often enclosed by a membrane derived from the rough endoplasmic reticulum or by cytoskeletal elements.[2][17]

In animal cells, virus particles are gathered by the microtubule-dependent aggregation of toxic or misfolded protein near the microtubule organizing center (MTOC), so the viroplasms of animal viruses are generally localized near the MTOC.[2][19] MTOCs are not found in plant cells. Plant viruses induce the rearrangement of membranes structures to form the viroplasm. This is mostly shown for plant RNA viruses.[17]

Functions

Viroplasm is the location within the infected cell where viral replication and assembly take place.[2] Wrapping the viroplasm with a membrane, concentrates the viral components required for the genome replication and the morphogenesis of new virus particles, so it increases the efficiency of the processes.[2] The recruitment of cellular membranes and cytoskeleton to generate virus replication sites can also benefit viruses in other ways. Disruption of cellular membranes can, for example, slow the transport of immunomodulatory proteins to the surface of infected cells and protect against innate and acquired immune responses, and rearrangements to cytoskeleton can facilitate virus release.[1] The viroplasm could also prevent virus degradation by proteases and nucleases.[17]

In the case of the Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV), viroplasms improve the virus transmission by the aphid vector. Viroplasms also control release of virions when the insect stings an infected plant cell or a cell near the infected cells.[16]

Possible co-evolution with the host

Aggregated structures may protect viral functional complexes from the cellular degradation systems. For example, formation of viral factories of the ASFV viroplasm is very similar to the aggresome formation.[2] An aggresome is a perinuclear site where misfolded proteins are transported and stored by the cell components for their destruction. It has been proposed that the viroplasm could be the product of a co-evolution between the virus and its host.[16] It is possible that a cellular response originally designed to reduce the toxicity of misfolded proteins is exploited by cytoplasmic viruses to improve their replication, the virus capsid synthesis, and assembly.[16] Alternatively, the activation of host defense mechanisms may involve sequestration of virus components in aggregates to prevent their dissemination, followed by their neutralisation. For example, viroplasms of mammalian viruses contain certain elements of the cellular degradation machinery which might enable cellular protective mechanisms against viral components.[20] Given the co-evolution of viruses with their host cells, changes in cell structure induced during infection are likely to involve a combination of the two strategies.[2]

Use in diagnostics

Presence of viroplasms is used to diagnose certain viral infections. Understanding the phenomena of virus aggregation and of the cell response to the presence of virus, and whether viroplasms facilitate or inhibit viral replication, may help to develop new therapeutic approaches against virus infections in animal and plant cells.[17]

See also

References

- Netherton C, Moffat K, Brooks E, Wileman T (2007). "A guide to viral inclusions, membrane rearrangements, factories, and viroplasm produced during virus replication". Advances in Virus Research. 70: 101–82. doi:10.1016/S0065-3527(07)70004-0. ISBN 9780123737281. PMC 7112299. PMID 17765705.

- Novoa RR, Calderita G, Arranz R, Fontana J, Granzow H, Risco C (February 2005). "Virus factories: associations of cell organelles for viral replication and morphogenesis". Biology of the Cell. 97 (2): 147–72. doi:10.1042/bc20040058. PMC 7161905. PMID 15656780.

- Xiong C, Muller S, Lebeurier G, Hirth L (1982). "Identification by immunoprecipitation of cauliflower mosaic virus in vitro major translation product with a specific serum against viroplasm protein". The EMBO Journal. 1 (8): 971–6. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01280.x. PMC 553144. PMID 16453427.

- Nilsson M, von Bonsdorff CH, Weclewicz K, Cohen J, Svensson L (March 1998). "Assembly of viroplasm and virus-like particles of rotavirus by a Semliki Forest virus replicon". Virology. 242 (2): 255–65. doi:10.1006/viro.1997.8987. PMID 9514960.

- Szajner P, Weisberg AS, Wolffe EJ, Moss B (July 2001). "Vaccinia virus A30L protein is required for association of viral membranes with dense viroplasm to form immature virions". Journal of Virology. 75 (13): 5752–61. doi:10.1128/JVI.75.13.5752-5761.2001. PMC 114291. PMID 11390577.

- Wei T, Kikuchi A, Suzuki N, Shimizu T, Hagiwara K, Chen H, Omura T (September 2006). "Pns4 of rice dwarf virus is a phosphoprotein, is localized around the viroplasm matrix, and forms minitubules". Archives of Virology. 151 (9): 1701–12. doi:10.1007/s00705-006-0757-4. PMID 16609816.

- Sodeik B, Doms RW, Ericsson M, Hiller G, Machamer CE, van 't Hof W, et al. (May 1993). "Assembly of vaccinia virus: role of the intermediate compartment between the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi stacks". The Journal of Cell Biology. 121 (3): 521–41. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.274.2733. doi:10.1083/jcb.121.3.521. PMC 2119557. PMID 8486734.

- Salas ML, Andrés G (April 2013). "African swine fever virus morphogenesis". Virus Research. 173 (1): 29–41. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2012.09.016. PMID 23059353.

- Suzan-Monti M, La Scola B, Barrassi L, Espinosa L, Raoult D (March 2007). "Ultrastructural characterization of the giant volcano-like virus factory of Acanthamoeba polyphaga Mimivirus". PLOS ONE. 2 (3): e328. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2..328S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000328. PMC 1828621. PMID 17389919.

- Abergel C, Legendre M, Claverie JM (November 2015). "The rapidly expanding universe of giant viruses: Mimivirus, Pandoravirus, Pithovirus and Mollivirus". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 39 (6): 779–96. doi:10.1093/femsre/fuv037. PMID 26391910.

- Tourís-Otero F, Cortez-San Martín M, Martínez-Costas J, Benavente J (August 2004). "Avian reovirus morphogenesis occurs within viral factories and begins with the selective recruitment of sigmaNS and lambdaA to microNS inclusions". Journal of Molecular Biology. 341 (2): 361–74. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2004.06.026. PMID 15276829.

- Fontana J, López-Iglesias C, Tzeng WP, Frey TK, Fernández JJ, Risco C (September 2010). "Three-dimensional structure of Rubella virus factories". Virology. 405 (2): 579–91. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2010.06.043. PMC 7111912. PMID 20655079.

- Lahaye X, Vidy A, Pomier C, Obiang L, Harper F, Gaudin Y, Blondel D (August 2009). "Functional characterization of Negri bodies (NBs) in rabies virus-infected cells: Evidence that NBs are sites of viral transcription and replication". Journal of Virology. 83 (16): 7948–58. doi:10.1128/JVI.00554-09. PMC 2715764. PMID 19494013.

- Evans AB, Peterson KE (August 2019). "Throw out the Map: Neuropathogenesis of the Globally Expanding California Serogroup of Orthobunyaviruses". Viruses. 11 (9): 794. doi:10.3390/v11090794. PMC 6784171. PMID 31470541.

- Karczewski MK, Strebel K (January 1996). "Cytoskeleton association and virion incorporation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif protein". Journal of Virology. 70 (1): 494–507. doi:10.1128/JVI.70.1.494-507.1996. PMC 189838. PMID 8523563.

- Bak A., Gargani D., Macia J-L., Malouvet E., Vernerey M_S., Blanc S. and Drucker, M. Virus factories of Cauliflower mosaic virus are virion reservoirs that engage actively in vector-transmission. 2013 journal of Virology

- Moshe A, Gorovits R (October 2012). "Virus-induced aggregates in infected cells". Viruses. 4 (10): 2218–32. doi:10.3390/v4102218. PMC 3497049. PMID 23202461.

- Shalla TA, Shepherd RJ, Petersen LJ (April 1980). "Comparative cytology of nine isolates of cauliflower mosaic virus". Virology. 102 (2): 381–8. doi:10.1016/0042-6822(80)90105-1. PMID 18631647.

- Wileman T (May 2006). "Aggresomes and autophagy generate sites for virus replication". Science. 312 (5775): 875–8. Bibcode:2006Sci...312..875W. doi:10.1126/science.1126766. PMID 16690857.

- Kopito RR (December 2000). "Aggresomes, inclusion bodies and protein aggregation". Trends in Cell Biology. 10 (12): 524–30. doi:10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01852-3. PMID 11121744.