Caudovirales

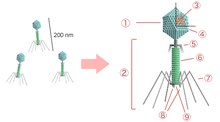

Caudovirales is an order of viruses known as the tailed bacteriophages (cauda is Latin for "tail").[1] Under the Baltimore classification scheme, the Caudovirales are group I viruses as they have double stranded DNA (dsDNA) genomes, which can be anywhere from 18,000 base pairs to 500,000 base pairs in length.[2] The virus particles have a distinct shape; each virion has an icosahedral head that contains the viral genome, and is attached to a flexible tail by a connector protein.[2] The order encompasses a wide range of viruses, many containing genes of similar nucleotide sequence and function. However, some tailed bacteriophage genomes can vary quite significantly in nucleotide sequence, even among the same genus. Due to their characteristic structure and possession of potentially homologous genes, it is believed these bacteriophages possess a common origin.[2]

| Caudovirales | |

|---|---|

| |

| From left to right: Myoviridae, Podoviridae, and Siphoviridae | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Duplodnaviria |

| Kingdom: | Heunggongvirae |

| Phylum: | Uroviricota |

| Class: | Caudoviricetes |

| Order: | Caudovirales |

| Families | |

|

See text | |

There are currently nine families, 44 subfamilies, 671 genera, and 1,967 species in the order. This makes Caudovirales the most populous order among viruses, accounting for approximately 30% of all recognized virus species and nearly half of all virus genera.[3]

Infection

Upon encountering a host bacterium, the tail section of the virion binds to receptors on the cell surface and delivers the DNA into the cell by use of an injectisome-like mechanism (an injectisome is a nanomachine that evolved for the delivery of proteins by type III secretion). The tail section of the virus punches a hole through the bacterial cell wall and plasma membrane and the genome passes down the tail into the cell. Once inside the genes are expressed from transcripts made by the host machinery, using host ribosomes. Typically, the genome is replicated by use of concatemers, in which overlapping segments of DNA are made, and then put together to form the whole genome.[2]

Assembly and maturation

Viral capsid proteins come together to form a precursor prohead, into which the genome enters. Once this has occurred, the prohead undergoes maturation by cleavage of capsid subunits to form an icosahedral phage head with 5-fold symmetry. After the head maturation, the tail is joined in one of two ways: Either the tail is constructed separately, and joined with the connector, or the tail is constructed directly onto the phage head. The tails consist of helix based proteins with 6-fold symmetry. After maturation of virus particles, the cell is lysed by lysins, holins, or a combination of the two.[2]

Taxonomy

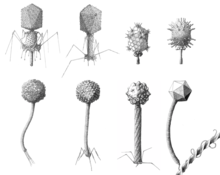

Because of the lack of homology between the amino acid and DNA sequences of these viruses these factors are precluded from being used as taxonomic markers as is common for other organisms, the three families discussed below (Myoviridae, Podoviridae, and Siphoviridae) are defined on the basis of morphology. This classification scheme was originated by Bradley in 1969 and has been extended since.[2]

All viruses in this order have icosahedral or oblate heads but differ in the length and contractile abilities of their tails. The Myoviridae have long tails that are contractile; the Podoviridae have short noncontractile tails; and the Siphoviridae have long noncontractile tails.[4] Siphoviridae constitute the majority of the known tailed viruses.[2][5]

Bradley referred to what is now known as the Myoviridae as type A, Siphoviridae as type B, and the Podoviridae as type C. He also divided his groups on the basis of head morphology: Within group A, A1 have small isometric heads; A2 have prolate heads; and A3 have elongated heads. Within groups B and C, numbers were similarly assigned: B1 and C1 have small isometric heads; B2 and C2 have prolate heads; and B3 and C3 have elongated heads.

In addition the aforementioned three families, a total of nine families and one incertae sedis genus exists in the order:[3]

- Ackermannviridae

- Autographiviridae

- Chaseviridae

- Demerecviridae

- Drexlerviridae

- Herelleviridae

- Myoviridae

- Podoviridae

- Siphoviridae

- Lilyvirus, the unassigned genus

Bacteriophage evolution

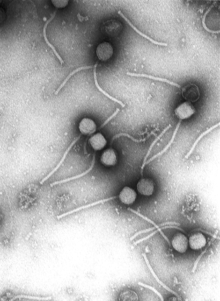

Bacteriophages occur in over 195 bacterial or archaeal genera. They arose repeatedly in different hosts and there are at least 11 separate lines of descent. Over 6300 bacteriophages have been examined in the electron microscope since 1959. Of these, more than 96 percent have tails. Of the tailed phages, about 57 percent have long, noncontractile tails (Siphoviridae). Tailed phages appear to be monophyletic and are the oldest known virus group.[5][6]

References

- Ackermann HW (1998). Tailed bacteriophages: the order caudovirales. Advances in Virus Research. 51. pp. 135–201. doi:10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60785-X. ISBN 9780120398515. PMID 9891587.

- "Double-Stranded DNA Bacteriophages". Boundless. 2017-11-11. Archived from the original on 2013-06-28.

- "Virus Taxonomy: 2019 Release". talk.ictvonline.org. International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- Maniloff, J.; Ackermann, H.W. (1998). "Taxonomy of bacterial viruses: establishment of tailed virus genera and the other Caudovirales". Archives of Virology. 143 (10): 2051–2063. doi:10.1007/s007050050442. PMID 9856093.

- Ackermann, H.W. (2003). "Bacteriophage observations and evolution". Research in Microbiology. 154 (4): 245–251. doi:10.1016/S0923-2508(03)00067-6. PMID 12798228.

- Ackermann, HW; Prangishvili, D (October 2012). "Prokaryote viruses studied by electron microscopy". Archives of Virology. 157 (10): 1843–9. doi:10.1007/s00705-012-1383-y. PMID 22752841.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Caudovirales. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Caudovirales |

- Xu J, Hendrix RW, Duda RL (2004). "Conserved translational frameshift in dsDNA bacteriophage tail assembly genes". Mol. Cell. 16 (1): 11–21. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.006. PMID 15469818.

- Casjens SR (2005). "Comparative genomics and evolution of the tailed-bacteriophages". Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8 (4): 451–8. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2005.06.014. PMID 16019256.