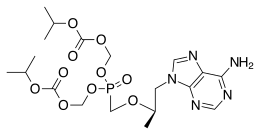

Tenofovir disoproxil

Tenofovir disoproxil, sold under the trade name Viread among others, is a medication used to treat chronic hepatitis B and to prevent and treat HIV/AIDS.[1] It is generally recommended for use with other antiretrovirals.[1] It may be used for prevention of HIV/AIDS among those at high risk before exposure, and after a needlestick injury or other potential exposure.[1] It is sold both by itself and together as emtricitabine/tenofovir and efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir.[1] It does not cure HIV/AIDS or hepatitis B.[1][2] It is available by mouth as a tablet or powder.[1]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌtəˈnoʊfəvɪər ˌdɪsəˈprɑːksəl/ |

| Trade names | Viread, others |

| Other names | Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, Bis(POC)PMPA |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a602018 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth (tablets) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 25% |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.129.993 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C19H30N5O10P |

| Molar mass | 519.448 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

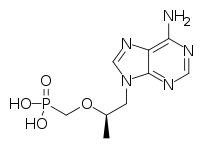

| Other names | 9-(2-Phosphonyl-methoxypropyly)adenine (PMPA) |

| MedlinePlus | a602018 |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | < 1% |

| Elimination half-life | 17 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.129.993 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C9H14N5O4P |

| Molar mass | 287.216 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Common side effects include nausea, rash, diarrhea, headache, pain, depression, and weakness.[1] Severe side effects include high blood lactate and an enlarged liver.[1] There are no absolute contraindications.[1] It is often recommended during pregnancy and appears to be safe.[1] It is a nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor and works by decreasing the ability of the viruses to replicate.[1]

Tenofovir was patented in 1996 and approved for use in the United States in 2001.[3] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[4] It is available as a generic medication as of 2017.[5]

Medical uses

Tenofovir disoproxil is used for HIV-1 infection and chronic hepatitis B treatment. For HIV-1 infection, tenofovir is indicated in combination with other antiretroviral agents for people 2 years of age and older. For chronic hepatitis B patients, tenofovir is indicated for patients 12 years of age and older.[6]

HIV risk reduction

Tenofovir can be used for HIV prevention in people who are at high risk for infection through sexual transmission or injecting drug use. A Cochrane review examined the use of tenofovir for prevention of HIV before exposure and found that both tenofovir alone and the tenofovir/emtricitabine combination decreased the risk of contracting HIV for high risk patients.[7] The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also conducted a study in partnership with the Thailand Ministry of Public Health to ascertain the effectiveness of providing people who inject drugs illicitly with daily doses of tenofovir as a prevention measure. The results revealed a 48.9% reduced incidence of the virus among the group of subjects who received the drug in comparison to the control group who received a placebo.[8]

Adverse effects

Tenofovir disoproxil is generally well tolerated with low discontinuation rates among the HIV and chronic hepatitis B population.[9] There are no contraindications for use of this drug.[6] The most commonly reported side effects due to use of tenofovir disoproxil were dizziness, nausea, and diarrhea.[9] Other adverse effects include depression, sleep disturbances, headache, itching, rash, and fever. The US box warning cautions potential onset of lactic acidosis or liver damage due to use of tenofovir disoproxil.[10]

Long term use of tenofovir disoproxil is associated with nephrotoxicity and bone loss. Presentation of nephrotoxicity can appear as Fanconi syndrome, acute kidney injury, or decline of glomerular filtration rate (GFR).[11] Discontinuation of tenofovir disoproxil can potentially lead to reversal of renal impairment. Nephrotoxicity may be due to proximal tubules accumulation of Tenofovir disoproxil leading to elevated serum concentrations.[9]

Interactions

Tenofovir interacts with didanosine and HIV-1 protease inhibitors. Tenofovir increases didanosine concentrations and can result in adverse effects such as pancreatitis and neuropathy. Tenofovir also interacts with HIV-1 protease inhibitors such as atazanavir, by decreasing atazanavir concentrations while increasing tenofovir concentrations.[6] In addition, since tenofovir is excreted by the kidney, medications that impair renal function can also cause problems.[12]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Tenofovir disoproxil is a nucleotide analog reverse-transcriptase inhibitor (NtRTI).[13] It selectively inhibits viral reverse transcriptase, a crucial enzyme in retroviruses such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), while showing limited inhibition of human enzymes, such as DNA polymerases α, β, and mitochondrial DNA polymerase γ.[6][13] In vivo tenofovir disoproxil fumarate is converted to tenofovir, an acyclic analog of deoxyadenosine 5'-monophosphate (d-AMP). Tenofovir lacks a hydroxyl group in the position corresponding to the 3' carbon of the d-AMP, preventing the formation of the 5′ to 3′ phosphodiester linkage essential for DNA chain elongation.[13] Once incorporated into a growing DNA strand, tenofovir causes premature termination of DNA transcription, preventing viral replication.[13]

Pharmacokinetics

Tenofovir disoproxil is a prodrug that is quickly absorbed from the gut and cleaved to release tenofovir.[6] Inside cells, tenofovir is phosphorylated to tenofovir diphosphate (which is analogous to a triphosphate, as tenofovir itself already has one phosphonate residue), the active compound that inhibits reverse transcriptase via chain termination.[12][13]

In fasting persons, bioavailability is 25%, and highest blood plasma concentrations are reached after one hour.[13] When taken with fatty food, highest plasma concentrations are reached after two hours, and the area under the curve is increased by 40%.[13] It is an inhibitor of cytochrome P450 1A2.[14]

Tenofovir is mainly excreted via the kidneys, both by glomerular filtration and by tubular secretion using the transport proteins OAT1, OAT3 and ABCC4.[12]

History

Tenofovir was initially synthesized by Antonín Holý at the Institute of Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic in Prague. The patent[15] filed by Holý in 1984 makes no mention of the potential use of the compound for the treatment of HIV infection, which had only been discovered one year earlier.

In 1985, De Clercq and Holý described the activity of PMPA against HIV in cell culture.[16] Shortly thereafter, a collaboration with the biotechnology company Gilead Sciences led to the investigation of PMPA's potential as a treatment for HIV infected patients. In 1997 researchers from Gilead and the University of California, San Francisco demonstrated that tenofovir exhibits anti-HIV effects in humans when dosed by subcutaneous injection.[17]

The initial form of tenofovir used in these studies had limited potential for widespread use because it poorly penetrated cells and was not absorbed when given by mouth. Gilead developed a pro-drug version of tenofovir, tenofovir disoproxil. This version of tenofovir is often referred to simply as "tenofovir". In this version of the drug, the two negative charges of the tenofovir phosphonic acid group are masked, thus enhancing oral absorption.

Tenofovir disoproxil was approved in the U.S. in 2001, for the treatment of HIV, and in 2008, for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B.[18][19]

Drug forms

Tenofovir disoproxil can be taken by mouth and is sold under the brand name Viread, among others.[20] Tenofovir disoproxil is a pro-drug form of tenofovir phosphonate, which is liberated intracellularly and converted to tenofovir disphophate.[21] It is marketed by Gilead Sciences (as the fumarate, abbreviated TDF).[22]

Tenofovir disoproxil is also available in pills which combine a number of antiviral drugs into a single dose. Well-known combinations include Atripla (tenofovir disoproxil/emtricitabine/efavirenz), Complera (tenofovir disoproxil/emtricitabine/rilpivirine), Stribild (tenofovir disoproxil/emtricitabine/elvitegravir/cobicistat), and Truvada (tenofovir disoproxil/emtricitabine).[20]

Gilead has created a second pro-drug form of the active drug, tenofovir diphosphate, called tenofovir alafenamide. It differs from tenofovir disoproxil due to its activation in the lymphoid cells. This allows the active metabolites to accumulate in those cells, leading to lower systemic exposure and potential toxicities.[9]

Chemistry

Tenofovir has a melting point of 279 °C (534 °F).[23] Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate is a white to off-white crystalline powder that is soluble in methanol, slightly soluble in water (13.4 mg/ml[24]), and very slightly soluble in dichloromethane.[25]

Detection in body fluids

Tenofovir may be measured in plasma by liquid chromatography. Such testing is useful for monitoring therapy and to prevent drug accumulation and toxicity in people with kidney or liver problems.[26][27][28]

References

- "Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 30 November 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- Martin P, Lau DT, Nguyen MH, Janssen HL, Dieterich DT, Peters MG, Jacobson IM (November 2015). "A Treatment Algorithm for the Management of Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection in the United States: 2015 Update". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 13 (12): 2071–87.e16. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2015.07.007. PMID 26188135.

- Fischer, Janos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 505. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- "Teva Announces Exclusive Launch of a Generic version of Viread in the United States". www.tevapharm.com.

- Gilead Sciences, Inc. Prescribing Information. Archived 2013-02-07 at the Wayback Machine Revised: November 2012.

- Okwundu CI, Uthman OA, Okoromah CA (July 2012). "Antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for preventing HIV in high-risk individuals". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7 (7): CD007189. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007189.pub3. PMID 22786505.

- Emma Bourke (14 June 2013). "Preventive drug could reduce HIV transmission among injecting drug users". The Conversation Australia. The Conversation Media Group. Archived from the original on 1 November 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- Ustianowski A, Arends JE (June 2015). "Tenofovir: What We Have Learnt After 7.5 Million Person-Years of Use". Infectious Diseases and Therapy. 4 (2): 145–57. doi:10.1007/s40121-015-0070-1. PMC 4471058. PMID 26032649.

- "Tenofovir: MedlinePlus Drug Information". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-11-10. Retrieved 2016-11-09.

- Morlat P, Vivot A, Vandenhende MA, Dauchy FA, Asselineau J, Déti E, Gerard Y, Lazaro E, Duffau P, Neau D, Bonnet F, Chêne G (2013-06-12). "Role of traditional risk factors and antiretroviral drugs in the incidence of chronic kidney disease, ANRS CO3 Aquitaine cohort, France, 2004-2012". PLOS One. 8 (6): e66223. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0066223. PMC 3680439. PMID 23776637.

- Haberfeld, H, ed. (2015). Austria-Codex (in German). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag.

- Drugbank: Tenofovir Archived 2015-09-08 at the Wayback Machine

- Pubchem. "Tenofovir disoproxil". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- "Patent US4808716 - 9-(phosponylmethoxyalkyl) adenines, the method of preparation and ... - Google Patents". Archived from the original on 2014-05-09.

- A US 4724233 A, De Clercq, Erik; Antonin Holy & Ivan Rosenberg, "Therapeutical application of phosphonylmethoxyalkyl adenines"

- Deeks SG, Barditch-Crovo P, Lietman PS, Hwang F, Cundy KC, Rooney JF, Hellmann NS, Safrin S, Kahn JO (September 1998). "Safety, pharmacokinetics, and antiretroviral activity of intravenous 9-[2-(R)-(Phosphonomethoxy)propyl]adenine, a novel anti-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) therapy, in HIV-infected adults". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 42 (9): 2380–4. doi:10.1128/aac.42.9.2380. PMC 105837. PMID 9736567.

- FDA letter of approval (regarding treatment of hepatitis B) Archived 2009-02-25 at the Wayback Machine

- FDA Clears Viread for Hepatitis B Archived 2017-09-08 at the Wayback Machine

- "Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products". www.accessdata.fda.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-11-10. Retrieved 2016-11-09.

- Mouton JP, Cohen K, Maartens G (November 2016). "Key toxicity issues with the WHO-recommended first-line antiretroviral therapy regimen". Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology. 9 (11): 1493–1503. doi:10.1080/17512433.2016.1221760. PMID 27498720.

- Emau P, Jiang Y, Agy MB, Tian B, Bekele G, Tsai CC (November 2006). "Post-exposure prophylaxis for SIV revisited: animal model for HIV prevention". AIDS Research and Therapy. 3: 29. doi:10.1186/1742-6405-3-29. PMC 1687192. PMID 17132170.

- Dinnendahl, V; Fricke, U, eds. (2011). Arzneistoff-Profile (in German). 9 (25 ed.). Eschborn, Germany: Govi Pharmazeutischer Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7741-9846-3.

- "AIDSinfo Drug Database: Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate". National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- "Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate" (PDF). World Health Organization. June 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-08-08.

- Delahunty T, Bushman L, Robbins B, Fletcher CV (July 2009). "The simultaneous assay of tenofovir and emtricitabine in plasma using LC/MS/MS and isotopically labeled internal standards". Journal of Chromatography B. 877 (20–21): 1907–14. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.05.029. PMC 2714254. PMID 19493710.

- Kearney BP, Yale K, Shah J, Zhong L, Flaherty JF (2006). "Pharmacokinetics and dosing recommendations of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in hepatic or renal impairment". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 45 (11): 1115–24. doi:10.2165/00003088-200645110-00005. PMID 17048975.

- R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, California, 2008, pp. 1490–1492.

External links

- "Tenofovir disoproxil". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.