Vaccine

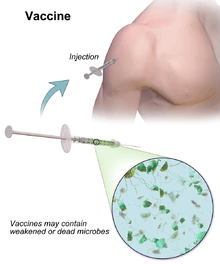

A vaccine is a biological preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious disease. A vaccine typically contains an agent that resembles a disease-causing microorganism and is often made from weakened or killed forms of the microbe, its toxins, or one of its surface proteins. The agent stimulates the body's immune system to recognize the agent as a threat, destroy it, and to further recognize and destroy any of the microorganisms associated with that agent that it may encounter in the future. Vaccines can be prophylactic (to prevent or ameliorate the effects of a future infection by a natural or "wild" pathogen), or therapeutic (to fight a disease that has already occurred, such as cancer).[1][2][3][4]

| Vaccine | |

|---|---|

Jonas Salk in 1955 holds two bottles of a culture used to grow polio vaccines. | |

| MeSH | D014612 |

The administration of vaccines is called vaccination. Vaccination is the most effective method of preventing infectious diseases;[5] widespread immunity due to vaccination is largely responsible for the worldwide eradication of smallpox and the restriction of diseases such as polio, measles, and tetanus from much of the world. The effectiveness of vaccination has been widely studied and verified; for example, vaccines that have proven effective include the influenza vaccine,[6] the HPV vaccine,[7] and the chicken pox vaccine.[8] The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that licensed vaccines are currently available for twenty-five different preventable infections.[9]

The terms vaccine and vaccination are derived from Variolae vaccinae (smallpox of the cow), the term devised by Edward Jenner to denote cowpox. He used it in 1798 in the long title of his Inquiry into the Variolae vaccinae Known as the Cow Pox, in which he described the protective effect of cowpox against smallpox.[10] In 1881, to honor Jenner, Louis Pasteur proposed that the terms should be extended to cover the new protective inoculations then being developed.[11]

Effectiveness

There is overwhelming scientific consensus that vaccines are a very safe and effective way to fight and eradicate infectious diseases.[13][14][15][16] Limitations to their effectiveness, nevertheless, exist.[17] Sometimes, protection fails because of vaccine-related failure such as failures in vaccine attenuation, vaccination regimes or administration or host-related failure due to host's immune system simply does not respond adequately or at all. Lack of response commonly results from genetics, immune status, age, health or nutritional status.[18] It also might fail for genetic reasons if the host's immune system includes no strains of B cells that can generate antibodies suited to reacting effectively and binding to the antigens associated with the pathogen.

Even if the host does develop antibodies, protection might not be adequate; immunity might develop too slowly to be effective in time, the antibodies might not disable the pathogen completely, or there might be multiple strains of the pathogen, not all of which are equally susceptible to the immune reaction. However, even a partial, late, or weak immunity, such as a one resulting from cross-immunity to a strain other than the target strain, may mitigate an infection, resulting in a lower mortality rate, lower morbidity, and faster recovery.

Adjuvants commonly are used to boost immune response, particularly for older people (50–75 years and up), whose immune response to a simple vaccine may have weakened.[19]

The efficacy or performance of the vaccine is dependent on a number of factors:

- the disease itself (for some diseases vaccination performs better than for others)

- the strain of vaccine (some vaccines are specific to, or at least most effective against, particular strains of the disease)[20]

- whether the vaccination schedule has been properly observed.

- idiosyncratic response to vaccination; some individuals are "non-responders" to certain vaccines, meaning that they do not generate antibodies even after being vaccinated correctly.

- assorted factors such as ethnicity, age, or genetic predisposition.

If a vaccinated individual does develop the disease vaccinated against (breakthrough infection), the disease is likely to be less virulent than in unvaccinated victims.[21]

The following are important considerations in the effectiveness of a vaccination program:[22]

- careful modeling to anticipate the effect that an immunization campaign will have on the epidemiology of the disease in the medium to long term

- ongoing surveillance for the relevant disease following introduction of a new vaccine

- maintenance of high immunization rates, even when a disease has become rare.

In 1958, there were 763,094 cases of measles in the United States; 552 deaths resulted.[23][24] After the introduction of new vaccines, the number of cases dropped to fewer than 150 per year (median of 56).[24] In early 2008, there were 64 suspected cases of measles. Fifty-four of those infections were associated with importation from another country, although only 13% were actually acquired outside the United States; 63 of the 64 individuals either had never been vaccinated against measles or were uncertain whether they had been vaccinated.[24]

Vaccines led to the eradication of smallpox, one of the most contagious and deadly diseases in humans.[25] Other diseases such as rubella, polio, measles, mumps, chickenpox, and typhoid are nowhere near as common as they were a hundred years ago thanks to widespread vaccination programs. As long as the vast majority of people are vaccinated, it is much more difficult for an outbreak of disease to occur, let alone spread. This effect is called herd immunity. Polio, which is transmitted only between humans, is targeted by an extensive eradication campaign that has seen endemic polio restricted to only parts of three countries (Afghanistan, Nigeria, and Pakistan).[26] However, the difficulty of reaching all children as well as cultural misunderstandings have caused the anticipated eradication date to be missed several times.

Vaccines also help prevent the development of antibiotic resistance. For example, by greatly reducing the incidence of pneumonia caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, vaccine programs have greatly reduced the prevalence of infections resistant to penicillin or other first-line antibiotics.[27]

The measles vaccine is estimated to prevent 1 million deaths every year.[28]

Adverse effects

Vaccination given during childhood is generally safe.[29] Adverse effects, if any, are generally mild.[30] The rate of side effects depends on the vaccine in question.[30] Some common side effects include fever, pain around the injection site, and muscle aches.[30] Additionally, some individuals may be allergic to ingredients in the vaccine.[31] MMR vaccine is rarely associated with febrile seizures.[29]

Severe side effects are extremely rare.[29] Varicella vaccine is rarely associated with complications in immunodeficient individuals and rotavirus vaccines are moderately associated with intussusception.[29]

At least 19 countries have no-fault compensation programs to provide compensation for those suffering severe adverse effects of vaccination.[32] The United States’ program is known as the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act and the United Kingdom employs the Vaccine Damage Payment.

Types

Vaccines contain dead or inactivated organisms or purified products derived from them.

There are several types of vaccines in use.[33] These represent different strategies used to try to reduce the risk of illness while retaining the ability to induce a beneficial immune response.

Inactivated

Some vaccines contain inactivated, but previously virulent, micro-organisms that have been destroyed with chemicals, heat, or radiation.[34] Examples include the polio vaccine, hepatitis A vaccine, rabies vaccine and some influenza vaccines.[35]

Attenuated

Some vaccines contain live, attenuated microorganisms. Many of these are active viruses that have been cultivated under conditions that disable their virulent properties, or that use closely related but less dangerous organisms to produce a broad immune response. Although most attenuated vaccines are viral, some are bacterial in nature. Examples include the viral diseases yellow fever, measles, mumps, and rubella, and the bacterial disease typhoid. The live Mycobacterium tuberculosis vaccine developed by Calmette and Guérin is not made of a contagious strain but contains a virulently modified strain called "BCG" used to elicit an immune response to the vaccine. The live attenuated vaccine containing strain Yersinia pestis EV is used for plague immunization. Attenuated vaccines have some advantages and disadvantages. They typically provoke more durable immunological responses and are the preferred type for healthy adults. But they may not be safe for use in immunocompromised individuals, and on rare occasions mutate to a virulent form and cause disease.[36]

Toxoid

Toxoid vaccines are made from inactivated toxic compounds that cause illness rather than the micro-organism.[37] Examples of toxoid-based vaccines include tetanus and diphtheria. Toxoid vaccines are known for their efficacy.[35] Not all toxoids are for micro-organisms; for example, Crotalus atrox toxoid is used to vaccinate dogs against rattlesnake bites.[38]

Subunit

Rather than introducing an inactivated or attenuated micro-organism to an immune system (which would constitute a "whole-agent" vaccine), a subunit vaccine uses a fragment of it to create an immune response. Examples include the subunit vaccine against hepatitis B virus that is composed of only the surface proteins of the virus (previously extracted from the blood serum of chronically infected patients, but now produced by recombination of the viral genes into yeast)[39] or as an edible algae vaccine, the virus-like particle (VLP) vaccine against human papillomavirus (HPV) that is composed of the viral major capsid protein,[40] and the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase subunits of the influenza virus.[35] A subunit vaccine is being used for plague immunization.[41]

Conjugate

Certain bacteria have polysaccharide outer coats that are poorly immunogenic. By linking these outer coats to proteins (e.g., toxins), the immune system can be led to recognize the polysaccharide as if it were a protein antigen. This approach is used in the Haemophilus influenzae type B vaccine.[42]

Heterotypic

Also known as heterologous or "Jennerian" vaccines, these are vaccines that are pathogens of other animals that either do not cause disease or cause mild disease in the organism being treated. The classic example is Jenner's use of cowpox to protect against smallpox. A current example is the use of BCG vaccine made from Mycobacterium bovis to protect against human tuberculosis.[43]

Experimental

A number of innovative vaccines are also in development and in use:

- Dendritic cell vaccines combine dendritic cells with antigens in order to present the antigens to the body's white blood cells, thus stimulating an immune reaction. These vaccines have shown some positive preliminary results for treating brain tumors [44] and are also tested in malignant melanoma.[45]

- DNA vaccination – an alternative, experimental approach to vaccination called DNA vaccination, created from an infectious agent's DNA, is under development. The proposed mechanism is the insertion (and expression, enhanced by the use of electroporation, triggering immune system recognition) of viral or bacterial DNA into human or animal cells. Some cells of the immune system that recognize the proteins expressed will mount an attack against these proteins and cells expressing them. Because these cells live for a very long time, if the pathogen that normally expresses these proteins is encountered at a later time, they will be attacked instantly by the immune system. One potential advantage of DNA vaccines is that they are very easy to produce and store. As of 2015, DNA vaccination is still experimental and is not approved for human use.

- Recombinant vector – by combining the physiology of one micro-organism and the DNA of another, immunity can be created against diseases that have complex infection processes. An example is the RVSV-ZEBOV vaccine licensed to Merck that is being used in 2018 to combat ebola in Congo.[46]

- RNA vaccine is a novel type of vaccine which is composed of the nucleic acid RNA, packaged within a vector such as lipid nanoparticles. A number of RNA vaccines are under development to combat the COVID-19 pandemic.

- T-cell receptor peptide vaccines are under development for several diseases using models of Valley Fever, stomatitis, and atopic dermatitis. These peptides have been shown to modulate cytokine production and improve cell-mediated immunity.

- Targeting of identified bacterial proteins that are involved in complement inhibition would neutralize the key bacterial virulence mechanism.[47]

While most vaccines are created using inactivated or attenuated compounds from micro-organisms, synthetic vaccines are composed mainly or wholly of synthetic peptides, carbohydrates, or antigens.

Valence

Vaccines may be monovalent (also called univalent) or multivalent (also called polyvalent). A monovalent vaccine is designed to immunize against a single antigen or single microorganism.[48] A multivalent or polyvalent vaccine is designed to immunize against two or more strains of the same microorganism, or against two or more microorganisms.[49] The valency of a multivalent vaccine may be denoted with a Greek or Latin prefix (e.g., tetravalent or quadrivalent). In certain cases, a monovalent vaccine may be preferable for rapidly developing a strong immune response.[50]

Nomenclature

Various fairly standardized abbreviations for vaccine names have developed, although the standardization is by no means centralized or global. For example, the vaccine names used in the United States have well-established abbreviations that are also widely known and used elsewhere. An extensive list of them provided in a sortable table and freely accessible, is available at a US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention web page.[51] The page explains that "The abbreviations [in] this table (Column 3) were standardized jointly by staff of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, ACIP Work Groups, the editor of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), the editor of Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (the Pink Book), ACIP members, and liaison organizations to the ACIP."[51] Some examples are "DTaP" for diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine, "DT" for diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, and "Td" for tetanus and diphtheria toxoids. At its page on tetanus vaccination,[52] the CDC further explains that "Upper-case letters in these abbreviations denote full-strength doses of diphtheria (D) and tetanus (T) toxoids and pertussis (P) vaccine. Lower-case "d" and "p" denote reduced doses of diphtheria and pertussis used in the adolescent/adult-formulations. The 'a' in DTaP and Tdap stands for 'acellular,' meaning that the pertussis component contains only a part of the pertussis organism."[52] Another list of established vaccine abbreviations is at the CDC's page called "Vaccine Acronyms and Abbreviations", with abbreviations used on U.S. immunization records.[53] The United States Adopted Name system has some conventions for the word order of vaccine names, placing head nouns first and adjectives postpositively. This is why the USAN for "OPV" is "poliovirus vaccine live oral" rather than "oral poliovirus vaccine".

Developing immunity

The immune system recognizes vaccine agents as foreign, destroys them, and "remembers" them. When the virulent version of an agent is encountered, the body recognizes the protein coat on the virus, and thus is prepared to respond, by first neutralizing the target agent before it can enter cells, and secondly by recognizing and destroying infected cells before that agent can multiply to vast numbers.

When two or more vaccines are mixed together in the same formulation, the two vaccines can interfere. This most frequently occurs with live attenuated vaccines, where one of the vaccine components is more robust than the others and suppresses the growth and immune response to the other components. This phenomenon was first noted in the trivalent Sabin polio vaccine, where the amount of serotype 2 virus in the vaccine had to be reduced to stop it from interfering with the "take" of the serotype 1 and 3 viruses in the vaccine.[54] This phenomenon has also been found to be a problem with the dengue vaccines currently being researched, where the DEN-3 serotype was found to predominate and suppress the response to DEN-1, −2 and −4 serotypes.[55]

Adjuvants and preservatives

Vaccines typically contain one or more adjuvants, used to boost the immune response. Tetanus toxoid, for instance, is usually adsorbed onto alum. This presents the antigen in such a way as to produce a greater action than the simple aqueous tetanus toxoid. People who have an adverse reaction to adsorbed tetanus toxoid may be given the simple vaccine when the time comes for a booster.[56]

In the preparation for the 1990 Persian Gulf campaign, whole cell pertussis vaccine was used as an adjuvant for anthrax vaccine. This produces a more rapid immune response than giving only the anthrax vaccine, which is of some benefit if exposure might be imminent.[57]

Vaccines may also contain preservatives to prevent contamination with bacteria or fungi. Until recent years, the preservative thiomersal (A.K.A. Thimerosal in the US and Japan) was used in many vaccines that did not contain live virus. As of 2005, the only childhood vaccine in the U.S. that contains thiomersal in greater than trace amounts is the influenza vaccine,[58] which is currently recommended only for children with certain risk factors.[59] Single-dose influenza vaccines supplied in the UK do not list thiomersal in the ingredients. Preservatives may be used at various stages of production of vaccines, and the most sophisticated methods of measurement might detect traces of them in the finished product, as they may in the environment and population as a whole.[60]

Schedule

In order to provide the best protection, children are recommended to receive vaccinations as soon as their immune systems are sufficiently developed to respond to particular vaccines, with additional "booster" shots often required to achieve "full immunity". This has led to the development of complex vaccination schedules. In the United States, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, which recommends schedule additions for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, recommends routine vaccination of children against[62] hepatitis A, hepatitis B, polio, mumps, measles, rubella, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, HiB, chickenpox, rotavirus, influenza, meningococcal disease and pneumonia.[63] The large number of vaccines and boosters recommended (up to 24 injections by age two) has led to problems with achieving full compliance. In order to combat declining compliance rates, various notification systems have been instituted and a number of combination injections are now marketed (e.g., Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and MMRV vaccine), which provide protection against multiple diseases.

Besides recommendations for infant vaccinations and boosters, many specific vaccines are recommended for other ages or for repeated injections throughout life—most commonly for measles, tetanus, influenza, and pneumonia. Pregnant women are often screened for continued resistance to rubella. The human papillomavirus vaccine is recommended in the U.S. (as of 2011)[64] and UK (as of 2009).[65] Vaccine recommendations for the elderly concentrate on pneumonia and influenza, which are more deadly to that group. In 2006, a vaccine was introduced against shingles, a disease caused by the chickenpox virus, which usually affects the elderly.

History

Prior to the introduction of vaccination with material from cases of cowpox (heterotypic immunisation), smallpox could be prevented by deliberate inoculation of smallpox virus, later referred to as variolation to distinguish it from smallpox vaccination. The earliest hints of the practice of inoculation for smallpox in China come during the 10th century.[66] The Chinese also practiced the oldest documented use of variolation, dating back to the fifteenth century. They implemented a method of "nasal insufflation" administered by blowing powdered smallpox material, usually scabs, up the nostrils. Various insufflation techniques have been recorded throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries within China.[67]:60 Two reports on the Chinese practice of inoculation were received by the Royal Society in London in 1700; one by Dr. Martin Lister who received a report by an employee of the East India Company stationed in China and another by Clopton Havers.[68]

Sometime during the late 1760s whilst serving his apprenticeship as a surgeon/apothecary Edward Jenner learned of the story, common in rural areas, that dairy workers would never have the often-fatal or disfiguring disease smallpox, because they had already contracted cowpox, which has a very mild effect in humans. In 1796, Jenner took pus from the hand of a milkmaid with cowpox, scratched it into the arm of an 8-year-old boy, James Phipps, and six weeks later inoculated (variolated) the boy with smallpox, afterwards observing that he did not catch smallpox.[69][70] Jenner extended his studies and in 1798 reported that his vaccine was safe in children and adults and could be transferred from arm-to-arm reducing reliance on uncertain supplies from infected cows.[10] Since vaccination with cowpox was much safer than smallpox inoculation,[71] the latter, though still widely practiced in England, was banned in 1840.[72]

The second generation of vaccines was introduced in the 1880s by Louis Pasteur who developed vaccines for chicken cholera and anthrax,[11] and from the late nineteenth century vaccines were considered a matter of national prestige, and compulsory vaccination laws were passed.[69]

The twentieth century saw the introduction of several successful vaccines, including those against diphtheria, measles, mumps, and rubella. Major achievements included the development of the polio vaccine in the 1950s and the eradication of smallpox during the 1960s and 1970s. Maurice Hilleman was the most prolific of the developers of the vaccines in the twentieth century. As vaccines became more common, many people began taking them for granted. However, vaccines remain elusive for many important diseases, including herpes simplex, malaria, gonorrhea, and HIV.[69][73]

Vaccines have eliminated naturally occurring smallpox, and nearly eliminated polio, while other diseases, such as typhus, rotavirus, hepatitis A and B and others are well controlled. Conventional vaccines cover a small number of diseases, but are not effective at controlling many other infections.

Whole organism vaccines

First generation vaccines are whole-organism vaccines – either live and weakened, or killed forms.[74] Live, attenuated vaccines, such as smallpox and polio vaccines, are able to induce killer T-cell (TC or CTL) responses, helper T-cell (TH) responses and antibody immunity. However, attenuated forms of a pathogen can convert to a dangerous form and may cause disease in immunocompromised vaccine recipients (such as those with AIDS). While killed vaccines do not have this risk, they cannot generate specific killer T cell responses and may not work at all for some diseases.[74]

Subunit vaccines

Second generation vaccines were developed to reduce the risks from live vaccines. These are subunit vaccines, consisting of specific protein antigens (such as tetanus or diphtheria toxoid) or recombinant protein components (such as the hepatitis B surface antigen). They can generate TH and antibody responses, but not killer T cell responses.

DNA vaccines

DNA vaccines are third generation vaccines. They contain DNA that codes for specific proteins (antigens) from a pathogen. The DNA is injected into the body and taken up by cells, whose normal metabolic processes synthesize proteins based on the genetic code in the plasmid that they have taken up. Because these proteins contain regions of amino acid sequences that are characteristic of bacteria or viruses, they are recognized as foreign and when they are processed by the host cells and displayed on their surface, the immune system is alerted, which then triggers immune responses.[74][75]

Alternatively, the DNA may be encapsulated in protein to facilitate cell entry. If this capsid protein is included in the DNA, the resulting vaccine can combine the potency of a live vaccine without reversion risks. In 1983, Enzo Paoletti and Dennis Panicali at the New York Department of Health devised a strategy to produce recombinant DNA vaccines by using genetic engineering to transform ordinary smallpox vaccine into vaccines that may be able to prevent other diseases.[76] They altered the DNA of cowpox virus by inserting a gene from other viruses (namely Herpes simplex virus, hepatitis B and influenza).[77][78]

In 2016 a DNA vaccine for the Zika virus began testing at the National Institutes of Health. The study was planned to involve up to 120 subjects between 18 and 35. Separately, Inovio Pharmaceuticals and GeneOne Life Science began tests of a different DNA vaccine against Zika in Miami. The NIH vaccine is injected into the upper arm under high pressure. Manufacturing the vaccines in volume remains unsolved.[79]

Clinical trials for DNA vaccines to prevent HIV are underway.[80]

Timeline

Economics of development

One challenge in vaccine development is economic: Many of the diseases most demanding a vaccine, including HIV, malaria and tuberculosis, exist principally in poor countries. Pharmaceutical firms and biotechnology companies have little incentive to develop vaccines for these diseases because there is little revenue potential. Even in more affluent countries, financial returns are usually minimal and the financial and other risks are great.[81]

Most vaccine development to date has relied on "push" funding by government, universities and non-profit organizations.[82] Many vaccines have been highly cost effective and beneficial for public health.[83] The number of vaccines actually administered has risen dramatically in recent decades.[84] This increase, particularly in the number of different vaccines administered to children before entry into schools may be due to government mandates and support, rather than economic incentive.[85]

Patents

The filing of patents on vaccine development processes can also be viewed as an obstacle to the development of new vaccines. Because of the weak protection offered through a patent on the final product, the protection of the innovation regarding vaccines is often made through the patent of processes used in the development of new vaccines as well as the protection of secrecy.[86]

According to the World Health Organization, the biggest barrier to local vaccine production in less developed countries has not been patents, but the substantial financial, infrastructure, and workforce expertise requirements needed for market entry. Vaccines are complex mixtures of biological compounds, and unlike the case of drugs, there are no true generic vaccines. The vaccine produced by a new facility must undergo complete clinical testing for safety and efficacy similar to that undergone by that produced by the original manufacturer. For most vaccines, specific processes have been patented. These can be circumvented by alternative manufacturing methods, but this required R&D infrastructure and a suitably skilled workforce. In the case of a few relatively new vaccines such as the human papillomavirus vaccine, the patents may impose an additional barrier.[87]

Production

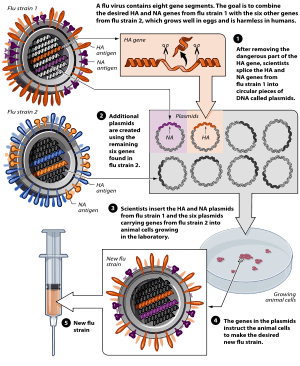

Vaccine production has several stages. First, the antigen itself is generated. Viruses are grown either on primary cells such as chicken eggs (e.g., for influenza) or on continuous cell lines such as cultured human cells (e.g., for hepatitis A).[88] Bacteria are grown in bioreactors (e.g., Haemophilus influenzae type b). Likewise, a recombinant protein derived from the viruses or bacteria can be generated in yeast, bacteria, or cell cultures. After the antigen is generated, it is isolated from the cells used to generate it. A virus may need to be inactivated, possibly with no further purification required. Recombinant proteins need many operations involving ultrafiltration and column chromatography. Finally, the vaccine is formulated by adding adjuvant, stabilizers, and preservatives as needed. The adjuvant enhances the immune response of the antigen, stabilizers increase the storage life, and preservatives allow the use of multidose vials.[89][90] Combination vaccines are harder to develop and produce, because of potential incompatibilities and interactions among the antigens and other ingredients involved.[91]

Vaccine production techniques are evolving. Cultured mammalian cells are expected to become increasingly important, compared to conventional options such as chicken eggs, due to greater productivity and low incidence of problems with contamination. Recombination technology that produces genetically detoxified vaccine is expected to grow in popularity for the production of bacterial vaccines that use toxoids. Combination vaccines are expected to reduce the quantities of antigens they contain, and thereby decrease undesirable interactions, by using pathogen-associated molecular patterns.[91]

In 2010, India produced 60 percent of the world's vaccine worth about $900 million (€670 million).[92]

Excipients

Beside the active vaccine itself, the following excipients and residual manufacturing compounds are present or may be present in vaccine preparations:[93]

- Aluminum salts or gels are added as adjuvants. Adjuvants are added to promote an earlier, more potent response, and more persistent immune response to the vaccine; they allow for a lower vaccine dosage.

- Antibiotics are added to some vaccines to prevent the growth of bacteria during production and storage of the vaccine.

- Egg protein is present in influenza and yellow fever vaccines as they are prepared using chicken eggs. Other proteins may be present.

- Formaldehyde is used to inactivate bacterial products for toxoid vaccines. Formaldehyde is also used to inactivate unwanted viruses and kill bacteria that might contaminate the vaccine during production.

- Monosodium glutamate (MSG) and 2-phenoxyethanol are used as stabilizers in a few vaccines to help the vaccine remain unchanged when the vaccine is exposed to heat, light, acidity, or humidity.

- Thiomersal is a mercury-containing antimicrobial that is added to vials of vaccine that contain more than one dose to prevent contamination and growth of potentially harmful bacteria. Due to the controversy surrounding thiomersal it has been removed from most vaccines except multi-use influenza, where it was reduced to levels so that a single dose contained less than 1 micro-gram of mercury, a level similar to eating 10 g of canned tuna.[94]

Role of preservatives

Many vaccines need preservatives to prevent serious adverse effects such as Staphylococcus infection, which in one 1928 incident killed 12 of 21 children inoculated with a diphtheria vaccine that lacked a preservative.[95] Several preservatives are available, including thiomersal, phenoxyethanol, and formaldehyde. Thiomersal is more effective against bacteria, has a better shelf-life, and improves vaccine stability, potency, and safety; but, in the U.S., the European Union, and a few other affluent countries, it is no longer used as a preservative in childhood vaccines, as a precautionary measure due to its mercury content.[96] Although controversial claims have been made that thiomersal contributes to autism, no convincing scientific evidence supports these claims.[97] Furthermore, a 10–11 year study of 657,461 children found that the MMR vaccine does not cause autism and actually reduced the risk of autism by 7 percent.[98][99]

Fill and finish

The final stage in vaccine manufacture before distribution is fill and finish, which is the process of filling vials with vaccines and packaging them for distribution. Although this is a conceptually simple part of the vaccine manufacture process, it is often a bottleneck in the process of distributing and adminstering vaccines.[100][101][102]

Delivery systems

The development of new delivery systems raises the hope of vaccines that are safer and more efficient to deliver and administer. Lines of research include liposomes and ISCOM (immune stimulating complex).[103]

Notable developments in vaccine delivery technologies have included oral vaccines. Early attempts to apply oral vaccines showed varying degrees of promise, beginning early in the 20th century, at a time when the very possibility of an effective oral antibacterial vaccine was controversial.[104] By the 1930s there was increasing interest in the prophylactic value of an oral typhoid fever vaccine for example.[105]

An oral polio vaccine turned out to be effective when vaccinations were administered by volunteer staff without formal training; the results also demonstrated increased ease and efficiency of administering the vaccines. Effective oral vaccines have many advantages; for example, there is no risk of blood contamination. Vaccines intended for oral administration need not be liquid, and as solids, they commonly are more stable and less prone to damage or to spoilage by freezing in transport and storage.[106] Such stability reduces the need for a "cold chain": the resources required to keep vaccines within a restricted temperature range from the manufacturing stage to the point of administration, which, in turn, may decrease costs of vaccines.

A microneedle approach, which is still in stages of development, uses "pointed projections fabricated into arrays that can create vaccine delivery pathways through the skin".[107]

An experimental needle-free[108] vaccine delivery system is undergoing animal testing.[109][110] A stamp-size patch similar to an adhesive bandage contains about 20,000 microscopic projections per square cm.[111] This dermal administration potentially increases the effectiveness of vaccination, while requiring less vaccine than injection.[112]

Plasmids

The use of plasmids has been validated in preclinical studies as a protective vaccine strategy for cancer and infectious diseases. However, in human studies, this approach has failed to provide clinically relevant benefit. The overall efficacy of plasmid DNA immunization depends on increasing the plasmid's immunogenicity while also correcting for factors involved in the specific activation of immune effector cells.[113]

Veterinary medicine

Vaccinations of animals are used both to prevent their contracting diseases and to prevent transmission of disease to humans.[114] Both animals kept as pets and animals raised as livestock are routinely vaccinated. In some instances, wild populations may be vaccinated. This is sometimes accomplished with vaccine-laced food spread in a disease-prone area and has been used to attempt to control rabies in raccoons.

Where rabies occurs, rabies vaccination of dogs may be required by law. Other canine vaccines include canine distemper, canine parvovirus, infectious canine hepatitis, adenovirus-2, leptospirosis, bordatella, canine parainfluenza virus, and Lyme disease, among others.

Cases of veterinary vaccines used in humans have been documented, whether intentional or accidental, with some cases of resultant illness, most notably with brucellosis.[115] However, the reporting of such cases is rare and very little has been studied about the safety and results of such practices. With the advent of aerosol vaccination in veterinary clinics for companion animals, human exposure to pathogens that are not naturally carried in humans, such as Bordetella bronchiseptica, has likely increased in recent years.[115] In some cases, most notably rabies, the parallel veterinary vaccine against a pathogen may be as much as orders of magnitude more economical than the human one.

DIVA vaccines

DIVA (Differentiation of Infected from Vaccinated Animals), also known as SIVA (Segregation of Infected from Vaccinated Animals), vaccines make it possible to differentiate between infected and vaccinated animals.

DIVA vaccines carry at least one epitope less than the microorganisms circulating in the field. An accompanying diagnostic test that detects antibody against that epitope allows us to actually make that differentiation.

First DIVA vaccines

The first DIVA vaccines (formerly termed marker vaccines and since 1999 coined as DIVA vaccines) and companion diagnostic tests have been developed by J.T. van Oirschot and colleagues at the Central Veterinary Institute in Lelystad, The Netherlands.[116] [117] They found that some existing vaccines against pseudorabies (also termed Aujeszky's disease) had deletions in their viral genome (among which was the gE gene). Monoclonal antibodies were produced against that deletion and selected to develop an ELISA that demonstrated antibodies against gE. In addition, novel genetically engineered gE-negative vaccines were constructed.[118] Along the same lines, DIVA vaccines and companion diagnostic tests against bovine herpesvirus 1 infections have been developed.[117][119]

Use in practice

The DIVA strategy has been applied in various countries and successfully eradicated pseudorabies virus. Swine populations were intensively vaccinated and monitored by the companion diagnostic test and, subsequently, the infected pigs were removed from the population. Bovine herpesvirus 1 DIVA vaccines are also widely used in practice.

Other DIVA vaccines (under development)

Scientists have put and still, are putting much effort in applying the DIVA principle to a wide range of infectious diseases, such as, for example, classical swine fever,[120] avian influenza,[121] Actinobacillus pleuropneumonia[122] and Salmonella infections in pigs.[123]

Trends

Vaccine development has several trends:[124]

- Until recently, most vaccines were aimed at infants and children, but adolescents and adults are increasingly being targeted.[124][125]

- Combinations of vaccines are becoming more common; vaccines containing five or more components are used in many parts of the world.[124]

- New methods of administering vaccines are being developed, such as skin patches, aerosols via inhalation devices, and eating genetically engineered plants.[124]

- Vaccines are being designed to stimulate innate immune responses, as well as adaptive.[124]

- Attempts are being made to develop vaccines to help cure chronic infections, as opposed to preventing disease.[124]

- Vaccines are being developed to defend against bioterrorist attacks such as anthrax, plague, and smallpox.[124]

- Appreciation for sex and pregnancy differences in vaccine responses "might change the strategies used by public health officials".[126]

- Scientists are now trying to develop synthetic vaccines by reconstructing the outside structure of a virus, this will help prevent vaccine resistance.[127]

Principles that govern the immune response can now be used in tailor-made vaccines against many noninfectious human diseases, such as cancers and autoimmune disorders.[128] For example, the experimental vaccine CYT006-AngQb has been investigated as a possible treatment for high blood pressure.[129] Factors that affect the trends of vaccine development include progress in translatory medicine, demographics, regulatory science, political, cultural, and social responses.[130]

Plants as bioreactors for vaccine production

Transgenic plants have been identified as promising expression systems for vaccine production. Complex plants such as tobacco, potato, tomato, and banana can have genes inserted that cause them to produce vaccines usable for humans.[131] Bananas have been developed that produce a human vaccine against hepatitis B.[132] Another example is the expression of a fusion protein in alfalfa transgenic plants for the selective directioning to antigen presenting cells, therefore increasing vaccine potency against Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus (BVDV).[133][134]

See also

- Vaccine cooler

- Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations

- Economics of vaccines

- Flying syringe

- The Horse Named Jim

- Immunization registry

- Immunotherapy

- List of vaccine ingredients

- List of vaccine topics

- Non-specific effect of vaccines

- OPV AIDS hypothesis

- Reverse vaccinology

- TA-CD

- Virosome

- Vaccine failure

- Vaccine hesitancy

- Vaccinov

- Virus-like particle

References

- Melief CJ, van Hall T, Arens R, Ossendorp F, van der Burg SH (September 2015). "Therapeutic cancer vaccines". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 125 (9): 3401–12. doi:10.1172/JCI80009. PMC 4588240. PMID 26214521.

- Bol KF, Aarntzen EH, Pots JM, Olde Nordkamp MA, van de Rakt MW, Scharenborg NM, de Boer AJ, van Oorschot TG, Croockewit SA, Blokx WA, Oyen WJ, Boerman OC, Mus RD, van Rossum MM, van der Graaf CA, Punt CJ, Adema GJ, Figdor CG, de Vries IJ, Schreibelt G (March 2016). "Prophylactic vaccines are potent activators of monocyte-derived dendritic cells and drive effective anti-tumor responses in melanoma patients at the cost of toxicity". Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 65 (3): 327–39. doi:10.1007/s00262-016-1796-7. PMC 4779136. PMID 26861670.

- Brotherton J (2015). "HPV prophylactic vaccines: lessons learned from 10 years experience". Future Virology. 10 (8): 999–1009. doi:10.2217/fvl.15.60.

- Frazer IH (May 2014). "Development and implementation of papillomavirus prophylactic vaccines". Journal of Immunology. 192 (9): 4007–11. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1490012. PMID 24748633.

-

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011). A CDC framework for preventing infectious diseases. Archived 2017-08-29 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 11 September 2012. "Vaccines are our most effective and cost-saving tools for disease prevention, preventing untold suffering and saving tens of thousands of lives and billions of dollars in healthcare costs each year."

- American Medical Association (2000). Vaccines and infectious diseases: putting risk into perspective. Archived 2015-02-05 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 11 September 2012. "Vaccines are the most effective public health tool ever created."

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Vaccine-preventable diseases. Archived 2015-03-13 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 11 September 2012. "Vaccines still provide the most effective, longest-lasting method of preventing infectious diseases in all age groups."

- United States National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). NIAID Biodefense Research Agenda for Category B and C Priority Pathogens. Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 11 September 2012. "Vaccines are the most effective method of protecting the public against infectious diseases."

- Fiore AE, Bridges CB, Cox NJ (2009). Seasonal influenza vaccines. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 333. pp. 43–82. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-92165-3_3. ISBN 978-3-540-92164-6. PMID 19768400.

- Chang Y, Brewer NT, Rinas AC, Schmitt K, Smith JS (July 2009). "Evaluating the impact of human papillomavirus vaccines". Vaccine. 27 (32): 4355–62. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.03.008. PMID 19515467.

- Liesegang TJ (August 2009). "Varicella zoster virus vaccines: effective, but concerns linger". Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology. 44 (4): 379–84. doi:10.3129/i09-126. PMID 19606157.

- World Health Organization, Global Vaccine Action Plan 2011-2020. Archived 2014-04-14 at the Wayback Machine Geneva, 2012.

- Baxby D (January 1999). "Edward Jenner's Inquiry; a bicentenary analysis". Vaccine. 17 (4): 301–7. doi:10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00207-2. PMID 9987167.

- Pasteur L (1881). "Address on the Germ Theory". Lancet. 118 (3024): 271–72. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)35739-8.

- "Measles | Vaccination | CDC". 2018-02-05.

- Orenstein WA, Bernier RH, Dondero TJ, Hinman AR, Marks JS, Bart KJ, Sirotkin B (1985). "Field evaluation of vaccine efficacy". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 63 (6): 1055–68. PMC 2536484. PMID 3879673.

- Jan 11, Hub staff report / Published; 2017 (2017-01-11). "The science is clear: Vaccines are safe, effective, and do not cause autism". The Hub. Retrieved 2019-04-16.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Ellenberg SS, Chen RT (1997). "The complicated task of monitoring vaccine safety". Public Health Reports. 112 (1): 10–20, discussion 21. PMC 1381831. PMID 9018282.

- "Vaccine Safety: The Facts". HealthyChildren.org. Retrieved 2019-04-16.

- Grammatikos AP, Mantadakis E, Falagas ME (June 2009). "Meta-analyses on pediatric infections and vaccines". Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 23 (2): 431–57. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2009.01.008. PMID 19393917.

- Wiedermann, Ursula; Garner-Spitzer, Erika; Wagner, Angelika (January 2016). "Primary vaccine failure to routine vaccines: Why and what to do?". Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 12 (1): 239–243. doi:10.1080/21645515.2015.1093263. PMC 4962729. PMID 26836329.

- Neighmond P (2010-02-07). "Adapting Vaccines For Our Aging Immune Systems". Morning Edition. NPR. Archived from the original on 2013-12-16. Retrieved 2014-01-09.

- Schlegel M, Osterwalder JJ, Galeazzi RL, Vernazza PL (August 1999). "Comparative efficacy of three mumps vaccines during disease outbreak in Eastern Switzerland: cohort study". BMJ. 319 (7206): 352. doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7206.352. PMC 32261. PMID 10435956.

- Préziosi MP, Halloran ME (September 2003). "Effects of pertussis vaccination on disease: vaccine efficacy in reducing clinical severity". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 37 (6): 772–9. doi:10.1086/377270. PMID 12955637.

- Miller, E.; Beverley, P. C. L.; Salisbury, D. M. (2002-07-01). "Vaccine programmes and policies". British Medical Bulletin. 62 (1): 201–211. doi:10.1093/bmb/62.1.201. ISSN 0007-1420. PMID 12176861.

- Orenstein WA, Papania MJ, Wharton ME (May 2004). "Measles elimination in the United States". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 189 Suppl 1 (Suppl 1): S1-3. doi:10.1086/377693. PMID 15106120.

- "Measles--United States, January 1-April 25, 2008". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 57 (18): 494–8. May 2008. PMID 18463608. Archived from the original on October 11, 2017.

- "WHO | Smallpox". WHO. World Health Organization. Retrieved 2019-04-16.

- "WHO South-East Asia Region certified polio-free". WHO. 27 March 2014. Archived from the original on 27 March 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- "19 July 2017 Vaccines promoted as key to stamping out drug-resistant microbes "Immunization can stop resistant infections before they get started, say scientists from industry and academia."". Archived from the original on July 22, 2017.

- Sullivan P (2005-04-13). "Maurice R. Hilleman dies; created vaccines". Wash. Post. Archived from the original on 2012-10-20. Retrieved 2014-01-09.

- Maglione MA, Das L, Raaen L, Smith A, Chari R, Newberry S, Shanman R, Perry T, Goetz MB, Gidengil C (August 2014). "Safety of vaccines used for routine immunization of U.S. children: a systematic review". Pediatrics. 134 (2): 325–37. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-1079. PMID 25086160.

- "Possible Side-effects from Vaccines". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2018-07-12. Archived from the original on 17 March 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- "Seasonal Flu Shot – Seasonal Influenza (Flu)". CDC. 2018-10-02. Archived from the original on 2015-10-01. Retrieved 2017-09-17.

- Looker C, Heath K (2011). "No-fault compensation following adverse events attributed to vaccination: a review of international programmes". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. Word Health Organisation. 89 (5): 371–8. doi:10.2471/BLT.10.081901. PMC 3089384. PMID 21556305.

- "Vaccine Types". National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. 2012-04-03. Archived from the original on 2015-09-05. Retrieved 2015-01-27.

- "Types of Vaccines". Archived from the original on 2017-07-29. Retrieved October 19, 2017.

- "Different Types of Vaccines | History of Vaccines". www.historyofvaccines.org. Retrieved 2019-06-14.

- Sinha JK, Bhattacharya S. A Text Book of Immunology (Google Book Preview). Academic Publishers. p. 318. ISBN 978-81-89781-09-5. Retrieved 2014-01-09.

- "Different Types of Vaccines | History of Vaccines". www.historyofvaccines.org. Retrieved 2019-05-03.

- "Types of Vaccines". coastalcarolinaresearch.com. Retrieved 2019-05-03.

- Philadelphia, The Children's Hospital of (2014-08-18). "A Look at Each Vaccine: Hepatitis B Vaccine". www.chop.edu. Retrieved 2019-06-14.

- "HPV Vaccine | Human Papillomavirus | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2019-05-13. Retrieved 2019-06-14.

- Williamson, E. D.; Eley, S. M.; Griffin, K. F.; Green, M.; Russell, P.; Leary, S. E.; Oyston, P. C.; Easterbrook, T.; Reddin, K. M. (December 1995). "A new improved sub-unit vaccine for plague: the basis of protection". FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology. 12 (3–4): 223–230. doi:10.1111/j.1574-695X.1995.tb00196.x. ISSN 0928-8244. PMID 8745007.

- "Polysaccharide Protein Conjugate Vaccines". www.globalhealthprimer.emory.edu. Retrieved 2019-06-14.

- Scott (April 2004). "Classifying Vaccines" (PDF). BioProcesses International: 14–23. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-12-12. Retrieved 2014-01-09.

- Kim W, Liau LM (January 2010). "Dendritic cell vaccines for brain tumors". Neurosurgery Clinics of North America. 21 (1): 139–57. doi:10.1016/j.nec.2009.09.005. PMC 2810429. PMID 19944973.

- Anguille S, Smits EL, Lion E, van Tendeloo VF, Berneman ZN (June 2014). "Clinical use of dendritic cells for cancer therapy". The Lancet. Oncology. 15 (7): e257-67. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70585-0. PMID 24872109.

- McKenzie, David (26 May 2018). "Fear and failure: How Ebola sparked a global health revolution". CNN. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- Meri S, Jördens M, Jarva H (December 2008). "Microbial complement inhibitors as vaccines". Vaccine. 26 Suppl 8: I113-7. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.11.058. PMID 19388175.

- "Monovalent" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- Polyvalent vaccine at Dorlands Medical Dictionary Archived March 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "Questions And Answers On Monovalent Oral Polio Vaccine Type 1 (mOPV1)'Issued Jointly By WHO and UNICEF'". Pediatric Oncall. 2 (8). 3. What advantages does mOPV1 have over trivalent oral polio vaccine (tOPV)?. 2005-01-08. Archived from the original on 2012-02-29.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Vaccine Names, archived from the original on 2016-05-26, retrieved 2016-05-21.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2018-08-07), Tetanus (Lockjaw) Vaccination, archived from the original on 2016-05-16, retrieved 2016-05-21.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2018-02-02), Vaccine Acronyms and Abbreviations [Abbreviations used on U.S. immunization records], archived from the original on 2017-06-02, retrieved 2017-05-22.

- Sutter RW, Cochi SL, Melnick JL (1999). "Live attenuated polio vaccines". In Plotkin SA, Orenstein WA (eds.). Vaccines. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders. pp. 364–408.

- Kanesa-thasan N, Sun W, Kim-Ahn G, Van Albert S, Putnak JR, King A, Raengsakulsrach B, Christ-Schmidt H, Gilson K, Zahradnik JM, Vaughn DW, Innis BL, Saluzzo JF, Hoke CH (April 2001). "Safety and immunogenicity of attenuated dengue virus vaccines (Aventis Pasteur) in human volunteers". Vaccine. 19 (23–24): 3179–88. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.559.8311. doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(01)00020-2. PMID 11312014.

- Engler, Renata J. M.; Greenwood, John T.; Pittman, Phillip R.; Grabenstein, John D. (2006-08-01). "Immunization to Protect the US Armed Forces: Heritage, Current Practice, and Prospects". Epidemiologic Reviews. 28 (1): 3–26. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxj003. ISSN 0193-936X. PMID 16763072.

- Sox, Harold C.; Liverman, Catharyn T.; Fulco, Carolyn E.; War, Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Health Effects Associated with Exposures During the Gulf (2000). Vaccines. National Academies Press (US).

- "Institute for Vaccine Safety – Thimerosal Table". Archived from the original on 2005-12-10.

- Wharton, Melinda E.; National Vaccine Advisory committee "U.S.A. national vaccine plan" Archived 2016-05-04 at the Wayback Machine

- "Measurements of Non-gaseous air pollutants > Metals". npl.co.uk. National Physics Laboratory. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

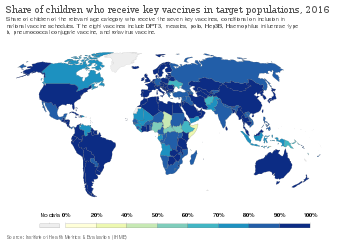

- "Share of children who receive key vaccines in target populations". Our World in Data. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- "ACIP Vaccine Recommendations Home Page". CDC. 2013-11-15. Archived from the original on 2013-12-31. Retrieved 2014-01-10.

- "Vaccine Status Table". Red Book Online. American Academy of Pediatrics. April 26, 2011. Archived from the original on December 27, 2013. Retrieved January 9, 2013.

- "HPV Vaccine Safety". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2013-12-20. Archived from the original on 2009-11-10. Retrieved 2014-01-10.

- "HPV vaccine in the clear". NHS choices. 2009-10-02. Archived from the original on 2014-01-10. Retrieved 2014-01-10.

- Needham, Joseph. (2000). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 6, Biology and Biological Technology, Part 6, Medicine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p.154

- Williams G (2010). Angel of Death. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-27471-6.

- Silverstein AM (2009). A History of Immunology (2nd ed.). Academic Press. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-08-091946-1..

- Stern AM, Markel H (2005). "The history of vaccines and immunization: familiar patterns, unew challenges". Health Affairs. 24 (3): 611–21. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.24.3.611. PMID 15886151.

- Dunn PM (January 1996). "Dr Edward Jenner (1749-1823) of Berkeley, and vaccination against smallpox" (PDF). Archives of Disease in Childhood: Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 74 (1): F77-8. doi:10.1136/fn.74.1.F77. PMC 2528332. PMID 8653442. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-08.

- Van Sant JE (2008). "The Vaccinators: Smallpox, Medical Knowledge, and the 'Opening' of Japan". J Hist Med Allied Sci. 63 (2): 276–79. doi:10.1093/jhmas/jrn014.

- Didgeon JA (May 1963). "Development of Smallpox Vaccine in England in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries". British Medical Journal. 1 (5342): 1367–72. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5342.1367. PMC 2124036. PMID 20789814.

- Baarda BI, Sikora AE (2015). "Proteomics of Neisseria gonorrhoeae: the treasure hunt for countermeasures against an old disease". Frontiers in Microbiology. 6: 1190. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.01190. PMC 4620152. PMID 26579097; Access provided by the University of Pittsburgh.

- Alarcon JB, Waine GW, McManus DP (1999). "DNA Vaccines: Technology and Application as Anti-parasite and Anti-microbial Agents". Advances in Parasitology Volume 42. Advances in Parasitology. 42. pp. 343–410. doi:10.1016/S0065-308X(08)60152-9. ISBN 9780120317424. PMID 10050276.

- Robinson HL, Pertmer TM (2000). DNA vaccines for viral infections: basic studies and applications. Advances in Virus Research. 55. pp. 1–74. doi:10.1016/S0065-3527(00)55001-5. ISBN 9780120398553. PMID 11050940.

- White LO, Gibb E, Newham HC, Richardson MD, Warren RC (July 1979). "Comparison of the growth of virulent and attenuated strains of Candida albicans in the kidneys of normal and cortison-treated mice by chitin assay". Mycopathologia. 67 (3): 173–7. doi:10.1007/bf00470753. PMID 384256.

- Paoletti E, Lipinskas BR, Samsonoff C, Mercer S, Panicali D (January 1984). "Construction of live vaccines using genetically engineered poxviruses: biological activity of vaccinia virus recombinants expressing the hepatitis B virus surface antigen and the herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 81 (1): 193–7. Bibcode:1984PNAS...81..193P. doi:10.1073/pnas.81.1.193. PMC 344637. PMID 6320164.

- US Patent 4722848 - Method for immunizing animals with synthetically modified vaccinia virus

- Regalado, Antonio. "The U.S. government has begun testing its first Zika vaccine in humans". Retrieved 2016-08-06.

- Chen Y, Wang S, Lu S (February 2014). "DNA Immunization for HIV Vaccine Development". Vaccines. 2 (1): 138–59. doi:10.3390/vaccines2010138. PMC 4494200. PMID 26344472.

- Goodman JL (2005-05-04). "Statement by Jesse L. Goodman, M.D., M.P.H. Director Center for Biologics, Evaluation and Research Food and Drug Administration U.S. Department of Health and Human Services on US Influenza Vaccine Supply and Preparations for the Upcoming Influenza Season before Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations Committee on Energy and Commerce United States House of Representatives". Archived from the original on 2008-09-21. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

- Olesen OF, Lonnroth A, Mulligan B (January 2009). "Human vaccine research in the European Union". Vaccine. 27 (5): 640–5. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.11.064. PMC 7115654. PMID 19059446.

- Jit M, Newall AT, Beutels P (April 2013). "Key issues for estimating the impact and cost-effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccination strategies". Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 9 (4): 834–40. doi:10.4161/hv.23637. PMC 3903903. PMID 23357859.

- Newall AT, Reyes JF, Wood JG, McIntyre P, Menzies R, Beutels P (February 2014). "Economic evaluations of implemented vaccination programmes: key methodological challenges in retrospective analyses". Vaccine. 32 (7): 759–65. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.11.067. PMID 24295806.

- Roser, Max; Vanderslott, Samantha (2013-05-10). "Vaccination". Our World in Data.

- Hardman Reis T (2006). "The role of intellectual property in the global challenge for immunization". J World Intellect Prop. 9 (4): 413–25. doi:10.1111/j.1422-2213.2006.00284.x.

- "www.who.int" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-11-23.

- "Three ways to make a vaccine" (infographic). Archived from the original on 2015-12-23. Retrieved 2015-08-05, in Stein, Rob (24 November 2009). "Vaccine system remains antiquated". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017.

- Muzumdar JM, Cline RR (2009). "Vaccine supply, demand, and policy: a primer". Journal of the American Pharmacists Association. 49 (4): e87-99. doi:10.1331/JAPhA.2009.09007. PMC 7185851. PMID 19589753.

- "Components of a vaccine". Archived from the original on 2017-06-13.

- Bae K, Choi J, Jang Y, Ahn S, Hur B (April 2009). "Innovative vaccine production technologies: the evolution and value of vaccine production technologies". Archives of Pharmacal Research. 32 (4): 465–80. doi:10.1007/s12272-009-1400-1. PMID 19407962.

- Staff (15 November 2011). "India produces 60 percent of world's vaccines". Indonesia. Antara. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 2015-08-05.

- CDC (2018-07-12). "Ingredients of Vaccines — Fact Sheet". Archived from the original on December 17, 2009. Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- The mercury levels in the table, unless otherwise indicated, are taken from: Mercury Levels in Commercial Fish and Shellfish (1990-2010) Archived 2015-05-03 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Accessed 8 January 2012.

- "Thimerosal in vaccines". Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2007-09-06. Archived from the original on 2013-01-06. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

- Bigham M, Copes R (2005). "Thiomersal in vaccines: balancing the risk of adverse effects with the risk of vaccine-preventable disease". Drug Safety. 28 (2): 89–101. doi:10.2165/00002018-200528020-00001. PMID 15691220.

- Offit PA (September 2007). "Thimerosal and vaccines--a cautionary tale". The New England Journal of Medicine. 357 (13): 1278–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMp078187. PMID 17898096.

- March 5, Reuters Updated; 2019 (2019-03-05). "Another study, this one of 657k kids, finds MMR vaccine doesn't cause autism | Montreal Gazette". Retrieved 2019-03-13.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Hoffman J (2019-03-05). "One More Time, With Big Data: Measles Vaccine Doesn't Cause Autism". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-03-13.

- "Vaccine Taskforce Aims" (PDF). assets.publishing.service.gov.uk. 6 April 2020. Retrieved 2020-07-26.

- Pagliusi, Sonia; Jarrett, Stephen; Hayman, Benoit; Kreysa, Ulrike; Prasad, Sai D.; Reers, Martin; Hong Thai, Pham; Wu, Ke; Zhang, Youn Tao; Baek, Yeong Ok; Kumar, Anand (July 2020). "Emerging manufacturers engagements in the COVID −19 vaccine research, development and supply". Vaccine. 38 (34): 5418–5423. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.06.022. PMC 7287474. PMID 32600908.

- Miller, Joe; Kuchler, Hannah (2020-04-28). "Drugmakers race to scale up vaccine capacity". www.ft.com. Retrieved 2020-07-26.

- Morein B, Hu KF, Abusugra I (June 2004). "Current status and potential application of ISCOMs in veterinary medicine". Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 56 (10): 1367–82. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2004.02.004. PMID 15191787.

- American Medicine. American-Medicine Publishing Company. 1926.

- South African Institute for Medical Research (1929). Annual report [Jaarverslag]. South African Institute for Medical Research – Suid-Afrikaanse Instituut vir Mediese Navorsing.

- Khan FA (2011-09-20). Biotechnology Fundamentals. CRC Press. p. 270. ISBN 978-1-4398-2009-4.

- Giudice EL, Campbell JD (April 2006). "Needle-free vaccine delivery". Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 58 (1): 68–89. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2005.12.003. PMID 16564111.

- WHO to trial Nanopatch needle-free delivery system| ABC News, 16 Sep 2014| "Needle-free polio vaccine a 'game-changer'". 2014-09-16. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-09-15.

- "Australian scientists develop 'needle-free' vaccination". The Sydney Morning Herald. 18 August 2013. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015.

- "Vaxxas raises $25m to take Brisbane's Nanopatch global". Business Review Weekly. 2015-02-10. Archived from the original on 2015-03-16. Retrieved 2015-03-05.

- "Australian scientists develop 'needle-free' vaccination". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 28 September 2011. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014.

- "Needle-free nanopatch vaccine delivery system". News Medical. 3 August 2011. Archived from the original on 11 May 2012.

- Lowe (2008). "Plasmid DNA as Prophylactic and Therapeutic vaccines for Cancer and Infectious Diseases". Plasmids: Current Research and Future Trends. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-35-6.

- Patel JR, Heldens JG (March 2009). "Immunoprophylaxis against important virus disease of horses, farm animals and birds". Vaccine. 27 (12): 1797–1810. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.12.063. PMC 7130586. PMID 19402200.

- Berkelman RL (August 2003). "Human illness associated with use of veterinary vaccines". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 37 (3): 407–14. doi:10.1086/375595. PMID 12884166.

- van Oirschot JT, Rziha HJ, Moonen PJ, Pol JM, van Zaane D (June 1986). "Differentiation of serum antibodies from pigs vaccinated or infected with Aujeszky's disease virus by a competitive enzyme immunoassay". The Journal of General Virology. 67 ( Pt 6) (6): 1179–82. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-67-6-1179. PMID 3011974.

- van Oirschot JT (August 1999). "Diva vaccines that reduce virus transmission". Journal of Biotechnology. 73 (2–3): 195–205. doi:10.1016/S0168-1656(99)00121-2. PMID 10486928.

- van Oirschot JT, Gielkens AL, Moormann RJ, Berns AJ (June 1990). "Marker vaccines, virus protein-specific antibody assays and the control of Aujeszky's disease". Veterinary Microbiology. 23 (1–4): 85–101. doi:10.1016/0378-1135(90)90139-M. PMID 2169682.

- Kaashoek MJ, Moerman A, Madić J, Rijsewijk FA, Quak J, Gielkens AL, van Oirschot JT (April 1994). "A conventionally attenuated glycoprotein E-negative strain of bovine herpesvirus type 1 is an efficacious and safe vaccine". Vaccine. 12 (5): 439–44. doi:10.1016/0264-410X(94)90122-8. PMID 8023552.

- Hulst MM, Westra DF, Wensvoort G, Moormann RJ (September 1993). "Glycoprotein E1 of hog cholera virus expressed in insect cells protects swine from hog cholera". Journal of Virology. 67 (9): 5435–42. doi:10.1128/JVI.67.9.5435-5442.1993. PMC 237945. PMID 8350404.

- Capua I, Terregino C, Cattoli G, Mutinelli F, Rodriguez JF (February 2003). "Development of a DIVA (Differentiating Infected from Vaccinated Animals) strategy using a vaccine containing a heterologous neuraminidase for the control of avian influenza". Avian Pathology. 32 (1): 47–55. doi:10.1080/0307945021000070714. PMID 12745380.

- Maas A, Meens J, Baltes N, Hennig-Pauka I, Gerlach GF (November 2006). "Development of a DIVA subunit vaccine against Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae infection". Vaccine. 24 (49–50): 7226–37. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.06.047. PMID 17027123.

- Leyman B, Boyen F, Van Parys A, Verbrugghe E, Haesebrouck F, Pasmans F (May 2011). "Salmonella Typhimurium LPS mutations for use in vaccines allowing differentiation of infected and vaccinated pigs". Vaccine. 29 (20): 3679–85. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.03.004. hdl:1854/LU-1201519. PMID 21419163. Archived from the original on 2017-10-28.

- Plotkin SA (April 2005). "Vaccines: past, present and future". Nature Medicine. 11 (4 Suppl): S5-11. doi:10.1038/nm1209. PMC 7095920. PMID 15812490.

- Carlson B (2008). "Adults now drive growth of vaccine market". Gen. Eng. Biotechnol. News. 28 (11). pp. 22–3. Archived from the original on 2014-01-10.

- Klein SL, Jedlicka A, Pekosz A (May 2010). "The Xs and Y of immune responses to viral vaccines". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 10 (5): 338–49. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70049-9. PMC 6467501. PMID 20417416.

- Staff (28 March 2013). "Safer vaccine created without virus". The Japan Times. Agence France-Presse – Jiji Press. Archived from the original on 30 March 2013. Retrieved 2013-03-28.

- Spohn G, Bachmann MF (February 2008). "Exploiting viral properties for the rational design of modern vaccines". Expert Review of Vaccines. 7 (1): 43–54. doi:10.1586/14760584.7.1.43. PMID 18251693.

- Samuelsson O, Herlitz H (March 2008). "Vaccination against high blood pressure: a new strategy". Lancet. 371 (9615): 788–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60355-4. PMID 18328909.

- Poland GA, Jacobson RM, Ovsyannikova IG (May 2009). "Trends affecting the future of vaccine development and delivery: the role of demographics, regulatory science, the anti-vaccine movement, and vaccinomics". Vaccine. 27 (25–26): 3240–4. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.01.069. PMC 2693340. PMID 19200833.

- Sala F, Manuela Rigano M, Barbante A, Basso B, Walmsley AM, Castiglione S (January 2003). "Vaccine antigen production in transgenic plants: strategies, gene constructs and perspectives". Vaccine. 21 (7–8): 803–8. doi:10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00603-5. PMID 12531364.

- Kumar GB, Ganapathi TR, Revathi CJ, Srinivas L, Bapat VA (October 2005). "Expression of hepatitis B surface antigen in transgenic banana plants". Planta. 222 (3): 484–93. doi:10.1007/s00425-005-1556-y. PMID 15918027.

- Ostachuk AI, Chiavenna SM, Gómez C, Pecora A, Pérez-Filgueira MD, Escribano JM, Ardila F, Dus MJ, Santos AW (2009). "Expression of a ScFv–E2T fusion protein in CHO-K1 cells and alfalfa transgenic plants for the selective directioning to antigen presenting cells". Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology. 128 (1): 315. doi:10.1016/j.vetimm.2008.10.224. Archived from the original on 2018-05-01.

- Peréz Aguirreburualde MS, Gómez MC, Ostachuk A, Wolman F, Albanesi G, Pecora A, Odeon A, Ardila F, Escribano JM, Dus Santos MJ, Wigdorovitz A (February 2013). "Efficacy of a BVDV subunit vaccine produced in alfalfa transgenic plants". Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology. 151 (3–4): 315–24. doi:10.1016/j.vetimm.2012.12.004. PMID 23291101.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Vaccines |

- Vaccines and Antisera at Curlie

- WHO Vaccine preventable diseases and immunization

- World Health Organization position papers on vaccines

- The History of Vaccines, from the College of Physicians of Philadelphia

- This website was highlighted by Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News in its "Best of the Web" section in January 2015. See: "The History of Vaccines". Best of the Web. Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News. 35 (2). 15 January 2015. p. 38.

- University of Oxford Vaccinology Programme: a series of short courses in vaccinology