Tynemouth Castle and Priory

Tynemouth Castle is located on a rocky headland (known as Pen Bal Crag), overlooking Tynemouth Pier. The moated castle-towers, gatehouse and keep are combined with the ruins of the Benedictine priory where early kings of Northumbria were buried. The coat of arms of the town of Tynemouth still includes three crowns commemorating the tradition that the Priory had been the burial place for three kings.

| Tynemouth Castle and Priory | |

|---|---|

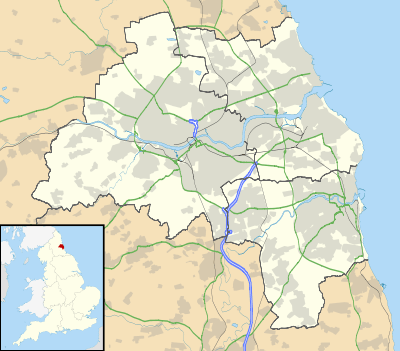

| Tynemouth, Tyne and Wear, England | |

Tynemouth Castle from the west | |

Tynemouth Castle and Priory | |

| Coordinates | 55.0175°N 1.4189°W |

| Type | Enclosure castle |

| Site information | |

| Owner | English Heritage |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Site history | |

| Built | 13–14th century |

| Materials | Stone |

Origins of the Priory

Little is known of the early history of the site. Some Roman stones have been found there, but there is no definite evidence that it was occupied by the Romans. The Priory was founded early in the 7th century, perhaps by Edwin of Northumbria. In 651 Oswin, king of Deira was murdered by the soldiers of King Oswiu of Bernicia, and subsequently his body was brought to Tynemouth for burial.[1] He became St Oswin and his burial place became a shrine visited by pilgrims. He was the first of the three kings buried at Tynemouth.

In 792 Osred II, who had been king of Northumbria from 789 to 790 and then deposed, was murdered. He also was buried at Tynemouth Priory.[1] Osred was the second of the three kings buried at Tynemouth. The third king to be buried at Tynemouth was Malcolm III, king of Scotland, who was killed at the Battle of Alnwick in 1093.[1] (This is the same Malcolm who appears in Shakespeare's Macbeth.) The king's body was sent north for reburial, in the reign of his son Alexander I, at Dunfermline Abbey, or possibly Iona.

Attacks by the Danes

In 800 the Danes plundered Tynemouth Priory,[1] and afterwards the monks strengthened the fortifications sufficiently to prevent the Danes from succeeding when they attacked again in 832. However, in 865 the church and monastery were destroyed by the Danes. At the same time, the nuns of St Hilda, who had come there for safety, were massacred. The priory was again plundered by the Danes in 870. The priory was destroyed by the Danes in 875.[1] The small parish church of St Mary remained.

Norman rule

Earl Tostig made Tynemouth his fortress during the reign of Edward the Confessor. By that time, the priory had been abandoned and the burial place of St Oswin had been forgotten. According to legend, St Oswin appeared in a vision to Edmund, a novice, who was living there as a hermit. The saint showed Edmund where his body lay and so the tomb was re-discovered in 1065. Tostig was killed at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066 and so was not able to re-found the monastery as he had intended.

In 1074 Waltheof II, Earl of Northumbria, last of the Anglo-Saxon earls, granted the church to the monks of Jarrow together with the body of St Oswin (Oswine of Deira), which was transferred to that site for a while. In 1090 Robert de Mowbray, Earl of Northumberland decided to re-found Tynemouth Priory, but he was in dispute with William de St-Calais, the Bishop of Durham and so placed the priory under the jurisdiction of the priory of St Albans. Monks were sent from St Albans in 1090 to colonise the new monastery. However, when the abbot of St Albans visited in 1093, Prior Thurgot of Durham met him and prevented the usurpation of the rights of Durham.

In 1091, seamen from William II's ships plundered Tynemouth and one victim appealed to St. Oswin, whose shrine was in the priory, and the next day the ships were all lost on the rocks of Coquet Island in fair weather. Thereafter, William Rufus held St. Oswin in great reverence.

In 1093 Malcolm III of Scotland invaded England and was killed at Alnwick by Robert de Mowbray. Malcolm's body was buried at Tynemouth Priory for a time, but it is believed that he was subsequently reburied in Dunfermline Abbey, in Scotland. In 1095 Robert de Mowbray took refuge in Tynemouth Castle after rebelling against William II. William besieged the castle and captured it after two months. Mowbray escaped to Bamburgh Castle, but subsequently returned to Tynemouth. The castle was re-taken and Mowbray was dragged from there and imprisoned for life for treason. In 1110 a new church was completed on the site.

The castle

It is believed that at the time of Robert Mowbray's capture in 1095 there was a castle on the site consisting of earthen ramparts and a wooden stockade. In 1296 the prior of Tynemouth was granted royal permission to surround the monastery with walls of stone, which he did. In 1390 a gatehouse and barbican were added on the landward side of the castle. Much remains of the priory structure as well as the castle gatehouse and walls which are 3200 feet (975 m) in length. The promontory was originally completely enclosed by a curtain wall and towers, but the north and east walls fell into the sea, and most of the south wall was demolished; the west wall, the gatehouse and a section of the south wall (with original wall walk) remain in good condition.

Edward II

In 1312 King Edward II took refuge in Tynemouth Castle together with his favourite Piers Gaveston, before fleeing by sea to Scarborough Castle. These events were dramatised by Christopher Marlowe in his play Edward II, published in 1594. Act 2 Scene 2 of the play is set 'Before Tynemouth Castle'; Act 2 Scene 3 is set 'Near Tynemouth Castle'; and Act 2 Scene 4 is set 'In Tynemouth Castle'.

Tynemouth Priory was also the resting place of Edward's illegitimate son Adam FitzRoy. FitzRoy accompanied his father in the Scottish campaigns of 1322, and died shortly afterwards on 18 September 1322, of unknown causes, and was buried at Tynemouth Priory on 30 September 1322; his father paid for a silk cloth with gold thread to be placed over his body.[2]

Reformation

In 1538 the monastery of Tynemouth was suppressed when Robert Blakeney was the last prior of Tynemouth. At that time, apart from the prior, there were fifteen monks and three novices in residence. The priory and its attached lands were taken over by King Henry VIII who granted them to Sir Thomas Hilton. The monastic buildings were dismantled leaving only the church and the Prior's house. The castle, however, remained in royal hands. New artillery fortifications were built from 1545 onwards, with the advice of Sir Richard Lee and the Italian military engineers Gian Tommaso Scala and Antonio da Bergamo. The medieval castle walls were updated with new gunports.[3] The castle was the birthplace of Henry Percy, 9th Earl of Northumberland in 1564, during the period when his father, the 8th Earl, was guardian of the castle.

In May 1594 George Selby and Thomas Power, lieutenant of Tynemouth Castle, captured two fugitives from the court of Anne of Denmark who had stolen some of her jewels. Power kept Jacob Kroger, a German goldsmith, and Guillaume Martyn, a French stableman, as prisoners at Tynemouth for five weeks until they were returned to Edinburgh for summary trial and execution.[4]

Subsequent history

Parish church

The church remained in use as a parish church until 1668 when a new church was built nearby. The ruins of the church can still be seen. Beneath them is a small (18 feet by 12 feet) chapel, the Oratory of St Mary or Percy Chapel. Its notable decorative features include a painted ceiling with numerous coats of arms and other symbols, stained-glass side windows, and a small rose window in the east wall, above the altar.

Lighthouse

For some time a navigation light, in the form of a coal-fired brazier, had been maintained on top of one of the turrets at the east end of the Priory church. It is not known when this practice began, but a source of 1582 refers to: "the kepinge of a continuall light in the night season at the easte ende of the churche of Tinmouthe castle ... for the more safegarde of such shippes as should passe by that coast".[5] As Governor of Tynemouth Castle, Henry Percy, 8th Earl of Northumberland is recorded as having responsibility for the light's maintenance; and he and his successors in that office were entitled to receive dues from passing ships in return.

In 1559, however, the stairs leading to the top of the turret collapsed, preventing the fire from being lit.[5] In 1665, therefore, the then Governor (Colonel Villiers) had a purpose-built lighthouse erected on the headland (within the castle walls, using stone taken from the priory); it was rebuilt in 1775.[6] Like its predecessor, the lighthouse was initially coal-fired, but in 1802 an oil-fired argand light was installed and by 1871 it displayed a revolving red light. In 1841 William Fowke (a descendant of Villiers and his successor as Governor) sold the lighthouse to Trinity House, London.[6] It remained in operation until 1895, when it was replaced by St. Mary's Lighthouse in Whitley Bay to the north. Tynemouth Castle Lighthouse was subsequently demolished, in 1898.[7]

Coastal defence and Coastguard station

At the end of the 19th century the castle was used as a barracks with several new buildings being added. Many of these were removed after a fire in 1936. The castle played a role during World War I and World War II[8] when it was used as a coastal defence installation covering the mouth of the river Tyne. The restored sections of the coastal defence emplacements are open to the public. These include a guardroom and the main armoury, where visitors can see how munitions were safely handled and protected.

More recently the site has hosted the modern buildings of Her Majesty's Coastguard; however the new coastguard station, built in 1980 and opened by Prince Charles, was closed in 2001.[9]

Present-day

Tynemouth Castle and Priory is now managed by English Heritage, which charges an admission fee.

In 2002, it doubled as a castle for a tourist advert for the Isle of Mull.

Governors [10]

- –1491 Sir Robert Lilburn[11]

- 1491– William de Norton [11]

- 1553– Henry Percy, 8th Earl of Northumberland

- 1561–1583 Sir Henry Percy, 8th Earl of Northumberland (reappointed)

- c.1647 Sir Arthur Haselrig (Governor of Newcastle and Tynemouth) [11]

- Colonel Henry Lilburne (Deputy Governor) (killed 1648)

- c.1655 John Topping (Deputy Governor)

- 1660– William Cavendish, 1st Duke of Newcastle

- c.1662– Colonel Edward Villiers (died 1689)

- c.1687–1707 Henry Villiers (died 1707)

- 1708–1710 Thomas Meredyth

- 1710–1750 Algernon Seymour, Earl of Hertford (died 1750)

- 1750–1771 Lt-Gen Sir Andrew Agnew, 5th Baronet

- 1771–1778 Lt-Gen Hon. Alex Mackay

- 1778–1796 Lt-Gen Lord Adam Gordon

- 1796–1809 General Charles Rainsford

- 1809–c.1820 David Douglas Wemyss [12]

Lieutenant Governors

- 1722–1753 Henry Villiers (died 1753) [11]

- 1753–1763 Lt-Gen Thomas Lacey

- 1763–1797 Lt-Col Spencer Cowper

- 1797–1799 Lt-Col Alexander Hope

- 1799–1821 Col. Charles Crawford

- 1821–1826 Lt-Gen James Hay

- 1826–1848 Lt-Gen William Thomas

Panorama

References

- "Priors, Kings and Soldiers". northtyneside.gov.uk. North Tyneside Council. 1 July 1999. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- F.D. Blackley, 'Adam, the bastard son of Edward II', Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research, xxxvii (1964), pp. 76–7.

- Colvin, Howard, ed., The History of the King's Works, vol. 4 part 2, (1982), 682–688.

- HMC 6th Report (Northumberland) (London, 1877), p. 232.

- "Tynemouth beacon". Tyne and Wear SiteLines (Historic Environment Record). Newcastle City Council. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- "Tynemouth lighthouse". Tyne and Wear SiteLines. Newcastle City Council. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- Jones, Robin (2014). Lighthouses of the North East Coast. Wellington, Somerset: Halsgrove.

- https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1015519

- "ENGLAND | North coastguard station closes". BBC News. 28 September 2001. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- Gibson, William. The History of the Monastery Founded at Tynemouth, in the Diocese ..., Volume 2. p. 125.

- "The Castle of Tynemouth-A Tale" (PDF). Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- "No. 16261". The London Gazette. 27 May 1809. p. 760.

Further reading

- Dodds, G.L., "Historic Sites of Northumberland & Newcastle upon Tyne", 2000, Albion Press, ISBN 0-9525122-1-1.