Tewkesbury Abbey

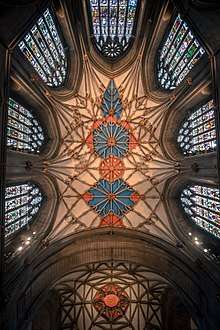

The Abbey Church of St Mary the Virgin, Tewkesbury, (commonly known as Tewkesbury Abbey), in the English county of Gloucestershire, is a parish church and a former Benedictine monastery. It is one of the finest examples of Norman architecture in Britain, and has probably the largest Romanesque crossing tower in Europe.

| Parish Church of St Mary the Virgin | |

|---|---|

Tewkesbury Abbey | |

| |

| 51°59′25″N 2°9′38″W | |

| Country | England, United Kingdom |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Churchmanship | High church / Modern Catholic |

| Website | www.tewkesburyabbey.org.uk |

| History | |

| Dedication | St Mary the Virgin |

| Administration | |

| Parish | Tewkesbury |

| Diocese | Gloucester |

| Province | Canterbury |

| Clergy | |

| Vicar(s) | The Revd Canon Paul Williams |

| Laity | |

| Organist/Director of music | Carleton Etherington |

| Organist(s) | Simon Bell |

| Churchwarden(s) | Peter Smail, Nicola Hawley, John Parkes |

Tewkesbury had been a centre for worship since the 7th century, becoming a priory in the 10th. The present building was started in the early 12th century. It was unsuccessfully used as a sanctuary in the Wars of the Roses. After the Dissolution of the Monasteries it became the parish church for the town. George Gilbert Scott led Restoration in the late 19th century. The church and churchyard within the abbey precincts includes tombs and memorials to many of the aristocracy of the area.

Services have been high church but now include Parish Eucharist, choral Mass and Evensong. These are accompanied by one of the church's three organs and choirs. There is a ring of twelve bells, hung for change ringing.

History

The Chronicle of Tewkesbury records that the first Christian worship was brought to the area by Theoc, a missionary from Northumbria, who built his cell in the mid-7th century near a gravel spit where the Severn and Avon rivers join together. The cell was succeeded by a monastery in 715,[2] but nothing remaining of it has been identified.

In the 10th century the religious foundation at Tewkesbury became a priory subordinate to the Benedictine Cranborne Abbey in Dorset.[3] In 1087, William the Conqueror gave the manor of Tewkesbury to his cousin, Robert Fitzhamon, who, with Giraldus, Abbot of Cranborne,[4] founded the present abbey in 1092.[5] Building of the present Abbey church did not start until 1102,[2] employing Caen stone imported from Normandy and floated up the Severn.[6]

Robert Fitzhamon was wounded at Falaise in Normandy in 1105 and died two years later, but his son-in-law, Robert FitzRoy, the natural son of Henry I who was made Earl of Gloucester, continued to fund the building work. The Abbey's greatest single later patron was Lady Eleanor le Despenser, last of the De Clare heirs of FitzRoy.[7] In the High Middle Ages, Tewkesbury became one of the richest abbeys of England.

After the Battle of Tewkesbury in the Wars of the Roses on 4 May 1471, some of the defeated Lancastrians sought sanctuary in the abbey.[8] The victorious Yorkists, led by King Edward IV, forced their way into the abbey; the resulting bloodshed caused the building to be closed for a month until it could be purified and re-consecrated.

At the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the last abbot, John Wakeman, surrendered the abbey to the commissioners of King Henry VIII on 9 January 1539. Perhaps because of his cooperation with the proceedings, he was awarded an annuity of 400 marks and was ordained as the first Bishop of Gloucester in September 1541.[9] Meanwhile, the people of Tewkesbury saved the abbey from destruction. Insisting that it was their parish church which they had the right to keep, they bought it from the Crown for the value of its bells and lead roof which would have been salvaged and melted down, leaving the structure a roofless ruin.[10] The price came to £453.

The bells merited their own free-standing belltower, an unusual feature in English sites. After the Dissolution, the bell-tower was used as the gaol for the borough until it was demolished in the late 18th century.[11]

The central stone tower was originally topped with a wooden spire, which collapsed in 1559 and was never rebuilt. Restoration undertaken in the late 19th century under Sir George Gilbert Scott was reopened on 23 September 1879.[12] Work continued under the direction of his son John Oldrid Scott until 1910 and included the rood screen of 1892.[13]

Flood waters from the nearby River Severn reached inside the Abbey during severe floods in 1760, and again on 23 July 2007.[14]

Construction time-line

- 23 October 1121 – the choir consecrated

- 1150 – tower and nave completed

- 1178 – large fire necessitated some rebuilding

- ~1235 – Chapel of St Nicholas built

- ~1300 – Chapel of St. James built

- 1321–1335 – choir rebuilt with radiating chantry chapels

- 1349–59 – tower and nave vaults rebuilt; the lierne vaults of the nave replacing wooden roofing

- 1400–1410 – cloisters rebuilt

- 1438 – Chapel of Isabel (Countess of Warwick) built

- 1471 – Battle of Tewkesbury; bloodshed within church so great that it is closed for purification

- 1520 – Guesten house completed (later became the vicar)

The building

The church itself is one of the finest Norman buildings in England.[15] Its massive crossing tower is noted in Pevsner's Buildings of England to be "probably the largest and finest Romanesque example in England"[16]. Fourteen of England's cathedrals are of smaller dimensions, while only Westminster Abbey contains more medieval church monuments.[17]

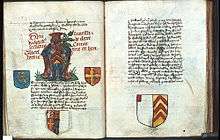

Notable monuments

Notable church monuments surviving in Tewkesbury Abbey include:

- 1107 – when the abbey's founder Robert Fitzhamon died in 1107, he was buried in the chapter house while his son-in-law Robert FitzRoy, Earl of Gloucester (an illegitimate son of King Henry I), continued building the abbey

- 1375 – Edward Despenser, Lord of the Manor of Tewkesbury, is remembered today chiefly for the effigy on his monument, which shows him in full colour kneeling on top of the canopy of his chantry, facing toward the high altar

- 1395 – Robert Fitzhamon's remains were moved into a new chapel built as his tomb

- 1471 – a brass plate on the floor in the centre of the sanctuary marks the grave of Edward of Westminster, Prince of Wales, the son of King Henry VI and end of the Lancastrian line, who was killed in the Battle of Tewkesbury – the only Prince of Wales ever to die in battle. He was aged only 17 at his death.

- 1478 – the bones of George, Duke of Clarence (brother of Edward IV and Richard III), and his wife Isabel (daughter of "Warwick, the Kingmaker") are housed behind a glass window in a wall of their inaccessible burial vault behind the high altar

- 1539 – the cadaver monument which Abbot Wakeman had erected for himself is only a cenotaph because he was not buried there

- Also buried in the abbey are several members of the Despenser, de Clare and Beauchamp families, all of whom were generous benefactors of the abbey. Such members include Henry de Beauchamp, 1st Duke of Warwick, and his wife, Cecily Neville, Duchess of Warwick, sister of "Warwick, the Kingmaker".

Other burials

|

|

The Three Organs

- The Abbey's 17th-century organ – known as the Milton Organ – was originally made for Magdalen College, Oxford, by Robert Dallam. After the English Civil War it was removed to the chapel of Hampton Court Palace, where the poet Milton may have played it.[18] It came to Tewkesbury in 1737. Since then, it has undergone several major rebuilds. A specification of the organ can be found on the National Pipe Organ Register.[19]

- In the North Transept is the stupendous Grove Organ, built by the short-lived partnership of Michell & Thynne in 1885: .

- The third organ in the Abbey is the Elliott chamber organ of 1812, mounted on a movable platform: .

List of organists

|

|

The bells

The bells at the Abbey were overhauled in 1962. The ring is now made up of twelve bells, hung for change ringing, cast in 1962, by John Taylor & Co of Loughborough.[30] The inscriptions of the old 5th and 10th bells are copied in facsimile onto the new bells. The bells have modern cast iron headstocks and all run on self-aligning ball bearings. They are hung in the north-east corner of the tower, and the ringing chamber is partitioned off from the rest of the tower. A semitone bell[30][31] was added (Flat 6th) also cast by Taylor of Loughborough in 1991, this is numbered 5a making the total 13 available to campanologists.

The Old Clock Bells are the old 6th (Abraham Rudhall II, 1725), the old 7th (Abraham Rudhall I, 1696), the old 8th (Abraham Rudhall I, 1696) and the old 11th (Abraham Rudhall I, 1717). In St Dunstan's Chapel, at the east end of the Abbey, is a small disused bell inscribed T. MEARS FECT. 1837.

The Abbey bells are rung from 10:15am to 11:00am every Sunday except the first Sunday of the month (a quarter peal). There is also ringing for Evensong from 4:00pm to 5:00pm, except on the third Sunday (a quarter peal) and most fifth Sundays. Practice takes place each Thursday from 7:30pm to 9:00pm.[30]

Churchyard

The churchyard contains war graves of two World War II Royal Air Force personnel.[32]

Abbey precincts

The market town of Tewkesbury developed to the north of the abbey precincts, of which vestiges remain in the layout of the streets and a few buildings: the Abbot's gatehouse, the Almonry barn, the Abbey Mill, Abbey House, the present vicarage and some half-timbered dwellings in Church Street. The Abbey now sits partly isolated in lawns, like a cathedral in its cathedral close, for the area surrounding the Abbey is protected from development by the Abbey Lawn Trust, originally funded by a United States benefactor in 1962.[33]

Abbots

- Gerald of Avranches (1102[34]–1109).[35][36] Previously served as Abbot of Cranborne, when Tewkesbury was a dependent cell. Gerald was made Abbot when the abbey was transferred to Tewkesbury by William Rufus and Robert Fitz Haimon. He also previously served as chaplain to Hugh, Earl of Chester[37]

- Robert (1109–1123)[35]

- Benedict (1124–1137) Previously served as Prior of Tewkesbury[35]

- Roger (1137–1161)[35]

- Fromund (1162–1178)[35]

- Robert (1182–1183)[35][36]

- The Bishop of St. David's held the priory for three years (1183–1186)[35]

- Alan of Tewkesbury, (1186–1202).[38] His tomb is in the south ambulatory of the choir

- Walter (1202–1213). Previously served as the Sacrist at Tewkesbury[35]

- Hugh or Henry (1212–1215). Previously served as Prior of Tewkesbury[35]

- Peter of Worcester (1216–1232)[39]

- Robert (1232–1254). Previously served as Prior of Tewkesbury.[39] A tomb thought to be his is in the south ambulatory

- Thomas de Stoke or Stokes (1255–1276). Previously served as Prior of St James' Priory, Bristol[36][39]

- Richard of Norton (1276–1282)[36][39]

- Thomas of Kempsey, Kemeseye, or Kemes (1282–1328)[36][39]

- John de Cotes (1330–1347). Previously served as Prior of Tewkesbury[39][40]

- Thomas de Leghe (1347–1361)[36][39]

- Thomas de Chesterton (1361–1389)[41]

- Thomas Parker (1389–1420)[41]

- William de Bristol, or de Bristow (1425–1442)[41]

- John de Abingdon (1444–1452)[41]

- John Galeys, Gales, or Galys (1452–1468)[41]

- John Streynesham, or Streynsham (1468–1480)[41]

- Richard Cheltenham, or Cheltynham (1480–1509)[41]

- Henry Beely, Beauley, Beley, or Beoly (1509–1534)[41]

- John Wyche alias John Wakeman (1534–1540). Last Abbot before the surrender of the monastery on 9 January 1540. Appointed Bishop of Gloucester in September 1541[42]

Choirs

The Abbey possesses, in effect, two choirs. The Abbey Choir sings at Sunday services, with children (boys and girls) and adults in the morning, and adults in the evening. Schola Cantorum is a professional choir of men and boys based at Dean Close Preparatory School and sings at weekday Evensongs as well as occasional masses and concerts. The Abbey School Tewkesbury, which educated, trained and provided choristers to sing the service of Evensong from its foundation in 1973 by Miles Amherst, closed in 2006; the choir was then re-housed at Dean Close School, Cheltenham, and renamed the Tewkesbury Abbey Schola Cantorum.

Worship

For the most part, worship at the Abbey has been emphatically High Anglican. However, in more recent times there has been an acknowledgement of the value of less solemn worship, and this is reflected in the two congregational services offered on Sunday mornings. The first of these (at 9.15am) is a Parish Eucharist, with modern language and an informal atmosphere; a parish breakfast is typically served after this service. The main Sung Eucharist at 11am is solemn and formal, including a choral Mass; traditional language is used throughout, and most parts of the service are indeed sung, including the Collect and Gospel reading. Choral Evensong is sung on Sunday evenings, and also on Monday, Tuesday, Thursday and Friday during the week. A said Eucharist also takes place every day of the week, at varying times, and alternating between traditional and modern language. Each summer since 1969 (with the exception of 2007 when the town was hit by floods) the Abbey has played host to Musica Deo Sacra, a festival combining music and liturgy. Photography in the Abbey is restricted.[43]

References

- Otherwise: Gules, a cross engrailed or

- Dugdale, William (1693). Monasticon Anglicanum, or, The history of the ancient abbies, and other monasteries, hospitals, cathedral and collegiate churches in England and Wales. With divers French, Irish, and Scotch monasteries formerly relating to England. Translated by Wright, James. London: Sam Keble and Hon Rhodes. pp. 15. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- "The priories of Cranborne and Horton". British History Online. Archived from the original on 18 August 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- Page, William. "'Houses of Benedictine monks: The priories of Cranbourne and Horton', in A History of the County of Dorset: Volume 2". British History Online. Victoria County History. Archived from the original on 18 June 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- Page, William. "Houses of Benedictine monks: The abbey of Tewkesbury in A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 2". British History Online. Victoria County History. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- "The misericords and history of Tewkesbury Abbey,". Misericords. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- Stober, Karen (2016). "Female Patrons of Late Medieval English Monasteries". Medieval Prosopography. 31: 115–136.

- "Battle of Tewkesbury (1471)". Battlefields of Britain Trust. Archived from the original on 29 August 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

-

- "The Bells of Tewkesbury Abbey". Tewksbury History Society. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- "The borough of Tewkesbury: Churches Pages 154-165 A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 8". British History Online. Victoria County History. Archived from the original on 9 December 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- "Religious Intelligence". The Cornishman (64). 2 October 1879. p. 8.

- David Verey and Alan Brooks. The Buildings of England Gloucestershire 2: The Vale and the Forest of Dean. Yale University Press. pp. 712–730.

- "Tewkesbury Abbey, Gloucestershire". UK Southwest. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- McAleer, J. Philip (1983). "The Romanesque Choir of Tewkesbury Abbey and the Problem of a "Colossal Order"". The Art Bulletin. 65 (4): 535–558. doi:10.2307/3050367.

- David Verey and Alan Brooks. The Buildings of England Gloucestershire 2: The Vale and the Forest of Dean. Yale University Press. p. 713.

- "Row on row". Church Monuments Society. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- Harper, John (May 1986). "The Organ of Magdalen College, Oxford. 1: The Historical Background of Earlier Organs, 1481–1985". The Musical Times, Vol. 127, No. 1718. Musical Times Publications Ltd.: 293–296. JSTOR 965479. (accessed via JSTOR, subscription required)

- "The National Pipe Organ Register - NPOR". www.npor.org.uk.

- The Ecclesiologist, Stevenson, 1855

- Kelly's Directory of Gloucestershire, 1879, p. 766

- Kelly's Directory of Gloucestershire, 1885, p. 600

- Kelly's Directory of Gloucestershire, 1897, p.328

- Who's who in Music; first post-War edition, 1949–50. Shaw Publishing

- "Obituary of Michael Howard". The Independent. London. 17 January 2002. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "Michael Peterson, organist". London: BBC. 8 October 2006. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- Shaw, Watkins (1991) The Succession of Organists of the Chapel Royal and the Cathedrals of England and Wales from c. 1538. Oxford: Clarendon Press ISBN 0-19-816175-1

- Who's who in Music. Shaw Publishing Ltd. First Post War Edition. 1949–50

- family archive Chorleys of Tewkesbury

- "Tewkesbury Abbey Bells". www.ringing.demon.co.uk. Archived from the original on 7 February 2006. Retrieved 4 March 2006.

- "History of Tewkesbury Abbey Abbey website". Archived from the original on 11 January 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- "CWGC Cemetery Report, details from casualty record". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 13 March 2007. Retrieved 4 March 2006.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link).

- Henry Laurd, ed. "Annales de Theokesberia" in Annales Monastici, 5 volumes (London: 1864-9) 1:44. "MCII: Hic primum in novum monasterium ingressi sumus" - "1102 A.D.: This was the first year we entered the new monastery".

- David Knowles, et al, The Heads of Religious Houses, England and Wales: Volume 1, 940-1216, revised edition (Cambridge, U.K.: 2001) pp. 73, 255-256.

- William Page, Victoria County History of Gloucester, Volume II (London: 1907) pp. 62-65.

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online (ODNB), "Robert Fitz Haimon" by Judith A. Green.

- ODNB, "Alan of Tewkesbury" by A. J. Duggan.

- David M. Smith, and Vera London, eds. The Heads of Religious Houses, England and Wales: Volume II, 1216-1377, (London: 2001) pp. 73-74.

- James Bennett, The History of Tewkesbury (London: 1830) p. 118.

- David M. Smith, ed. The Heads of Religious Houses, England and Wales: Volume III, 1377-1540, (Cambridge, U.K.: 2008) pp. 73-74.

- Archived 24 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine John Le Neve, et al., Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1541-1857: Volume 8, Bristol, Gloucester, Oxford and Peterborough Dioceses (London: 1996) p. 40.

- Note: Photography is permitted in the Abbey but requires purchase of a day permit. Photography is not permitted, however, during services or within the sanctuary of the altar and is not permitted for publication or commercial gain without written permission of the vicar or churchwardens. See: "Discover Tewkesbury Abbey" pamphlet and Tewkesbury Abbey Camera/Video Permit

- Morris, Richard K. & Shoesmith, Ron (editors) (2003) Tewkesbury Abbey: history, art and architecture. Almeley: Logaston Press ISBN 1-904396-03-8

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tewkesbury Abbey. |