Bamburgh Castle

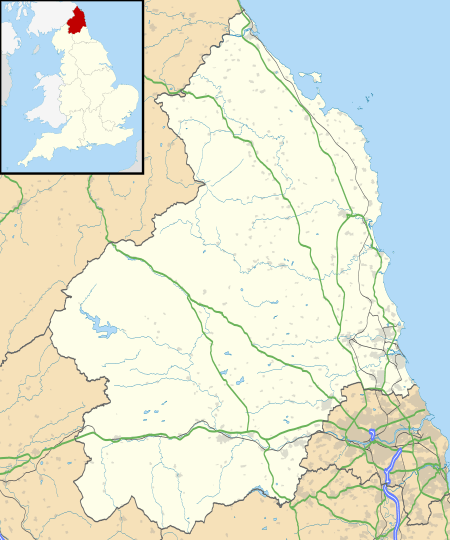

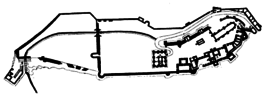

Bamburgh Castle is a castle on the northeast coast of England, by the village of Bamburgh in Northumberland. It is a Grade I listed building.[2]

| Bamburgh Castle | |

|---|---|

| Bamburgh, Northumberland | |

Bamburgh Castle from the northeast | |

Bamburgh Castle | |

| Coordinates | 55.608°N 1.709°W |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Armstrong family |

| Open to the public | Yes |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Designated | 4 January 1952 |

| Reference no. | 1280155[1] |

| Site history | |

| Built | 11th century |

The site was originally the location of a Celtic Brittonic fort known as Din Guarie and may have been the capital of the kingdom of Bernicia from its foundation in c. 420 to 547. After passing between the Britons and the Anglo-Saxons three times, the fort came under Anglo-Saxon control in 590. The fort was destroyed by Vikings in 993, and the Normans later built a new castle on the site, which forms the core of the present one. After a revolt in 1095 supported by the castle's owner, it became the property of the English monarch.

In the 17th century, financial difficulties led to the castle deteriorating, but it was restored by various owners during the 18th and 19th centuries. It was finally bought by the Victorian era industrialist William Armstrong, who completed its restoration. The castle still belongs to the Armstrong family and is open to the public.

History

Medieval history

Built on a dolerite outcrop, the location was previously home to a fort of the indigenous Celtic Britons known as Din Guarie[3] and may have been the capital of the kingdom of Bernicia, the realm of the Gododdin people,[4] from the realm's foundation in c. 420 until 547, the year of the first written reference to the castle. In that year the citadel was captured by the Anglo-Saxon ruler Ida of Bernicia (Beornice) and became Ida's seat.[5]

The castle was briefly retaken by the Britons from his son Hussa during the war of 590 before being retaken later the same year.[6] In c. 600, Hussa's successor Æthelfrith passed it on to his wife Bebba, from whom the early name Bebbanburh was derived.[7] Vikings destroyed the original fortification in 993.[8]

The Normans built a new castle on the site, which forms the core of the present one. William II unsuccessfully besieged it in 1095 during a revolt supported by its owner, Robert de Mowbray, Earl of Northumbria. After Robert was captured, his wife continued the defence until coerced to surrender by the king's threat to blind her husband.[9]

Bamburgh then became the property of the reigning English monarch. Henry II probably built the keep as it was complete by 1164.[10] Following the Siege of Acre in 1191, and as a reward for his service, King Richard I appointed Sir John Forster the first Governor of Bamburgh Castle.[11] Following the defeat of the Scots at the Battle of Neville's Cross in 1346, King David II was held prisoner at Bamburgh Castle.[9]

During the civil wars at the end of King John's reign, the castle was under the control of Philip of Oldcoates.[12] In 1464 during the Wars of the Roses, it became the first castle in England to be defeated by artillery, at the end of a nine-month siege by Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, the "Kingmaker", on behalf of the Yorkists.[13]

Modern history

The Forster family of Northumberland continued to provide the Crown with successive governors of the castle until the Crown granted ownership (or a lease according to some sources) of the church and the castle to another Sir John Forster in the mid 1500s, after the Dissolution of the Monasteries.[14][15] The family retained ownership until Sir William Forster (d. 1700) was posthumously declared bankrupt, and his estates, including the castle, were sold to Lord Crew, Bishop of Durham (husband of his sister Dorothy) under an Act of Parliament to settle the debts in 1704.[10]

Crewe placed the castle in the hands of a board of trustees chaired by Thomas Sharp, the Archdeacon of Northumberland. Following the death of Thomas Sharp, leadership of the board of trustees passed to John Sharp (Thomas Sharp's son) who refurbished the castle keep and court rooms[16] and established a hospital on the site.[17] In 1894, the castle was bought by the Victorian industrialist William Armstrong, who completed the restoration.[18]

During the Second World War, pillboxes were established in the sand dunes to protect the castle and surrounding area from German invasion[19] and, in 1944, a Royal Navy corvette was named HMS Bamborough Castle after the castle.[20] The castle still remains in the ownership of the Armstrong family.[18]

After the War, the castle became a Grade I Listed property. The description included this comment about the status of the building in 1952 and its history:[21]

Castle, divided into apartments. C12; ruinous when acquired by Lord Crewe in 1704 and made habitable after his death by Dr. Sharpe ... Acquired by Lord Armstrong, who had extensive restoration and rebuilding of high quality by C.J. Ferguson, 1894-1904. Squared sandstone and ashlar.

Location

About 9 miles (14 km) to the south on a point of coastal land is the ancient fortress of Dunstanburgh Castle and about 5 miles (8 km) to the north is Lindisfarne Castle on Holy Island. Inland about 16 miles (26 km) to the south is Alnwick Castle, the home of the Duke of Northumberland.[22]

Environmental factors

Air quality levels at Bamburgh Castle are excellent due to the absence of industrial sources in the region. Sound levels near the north–south road passing by Bamburgh Castle are in the range of 59 to 63 dBA in the daytime (Northumberland Sound Mapping Study, Northumberland, England, June 2003). Nearby are breeding colonies of Arctic and common terns on the inner Farne Islands, and of Atlantic puffin, European shag and razorbill on Staple Island.[23]

Archaeology at Bamburgh

Archaeological excavations were started in the 1960s by Brian Hope-Taylor, who discovered the gold plaque known as the Bamburgh Beast as well as the Bamburgh Sword.[24] Since 1996, the Bamburgh Research Project has been investigating the archaeology and history of the Castle and Bamburgh area. The project has concentrated on the fortress site and the early medieval burial ground at the Bowl Hole, to the south of the castle.[25]

During excavations at the Bowl Hole between 1998 and 2007, the remains of 110 individuals from the 7th and 8th century were discovered in that graveyard. Finally, in 2016, they were moved into the crypt of St Aidan's Church, Bamburgh; the crypt can be viewed by visitors through a small gate.[26]

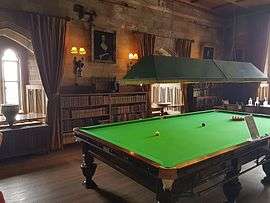

Armstrong and Aviation Artefacts Museum

The castle's laundry rooms feature the Armstrong and Aviation Artefacts Museum, with exhibits about Victorian industrialist William Armstrong and Armstrong Whitworth, the manufacturing company he founded. Displays include engines, artillery and weaponry, and aviation artefacts from two world wars.[27]

In popular culture

Selected literary appearances

The castle features in the ballad The Laidly Worm of Spindleston Heugh written in circa 1270.[28] Late medieval British author Thomas Malory identified Bamburgh Castle with Joyous Gard, the mythical castle home of Sir Launcelot in Arthurian legend.[29] In literature, Bamburgh, under its Saxon name Bebbanburg, is the home of Uhtred, the main character in Bernard Cornwell's The Saxon Stories. It features either as a significant location or as the inspiration for the protagonist in all books in the series, starting with The Last Kingdom, and the sequels The Pale Horseman, The Lords of the North, Sword Song, The Burning Land, Death of Kings, The Pagan Lord, The Empty Throne, Warriors of the Storm, The Flame Bearer and War of the Wolf.[30] The castle also features in the 2018 racing video game Forza Horizon 4, where it can be purchased by the player as one of their homes.[31]

Selected film appearances

In addition to appearances as itself, Bamburgh Castle has been used as a filming location for a number of television and film projects:

- 1927: Huntingtower[32]

- 1949: A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court[33]

- 1961: El Cid[34]

- 1964: Becket[35]

- 1971: The Devils[36]

- 1971: Macbeth[37]

- 1971: Mary, Queen of Scots[38]

- 1982: Ivanhoe[34]

- 1984–86: Robin of Sherwood[39]

- 1998: Elizabeth[34]

- 2011: Channel 4's Time Team dig at Bamburgh Castle[40]

- 2015: Macbeth (film)[41]

See also

References

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1280155)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1280155)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 5 December 2007.

- "Bernaccia (Bryneich / Berneich)". The History Files. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- 'An English empire: Bede and the early Anglo-Saxon kings' by N. J. Higham, Manchester University Press ND, 1995, ISBN 0-7190-4423-5, ISBN 978-0-7190-4423-6

- The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, entry for 547.

- Hope-Taylor, pp. 292-293

- Nennius. "Historia Brittonum, 8th century". Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- "Vikings invade Bamburgh Castle". Northumberland Gazette. 4 June 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- "Bamburgh Castle". Castles, forts and battles. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- "Bamburgh Castle". Historic England. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- "Sir John Forster". Find a grave. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- Todd, John M. (2004). "Oldcoates , Sir Philip of (d. 1220)" ((subscription or UK public library membership required)). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/27983. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Rickard, J (2013). "Siege of Bamburgh Castle, June-July 1464". History of War. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- Skulldugerous John Forster

- St Aidan Bamburgh History and Heritage

- "The Bamburgh Charities". Lord Crewe's Charities. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- "The Hidden Hospital: Bamburgh Castle Infirmary and Dispensary". History Today. 11 August 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- "Bamburgh Castle". William Armstrong. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- "Tidal surge uncovers wartime structure at Bamburgh beach". Evening Chronicle. 11 December 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- "HMS Bamburgh Castle". Naval History. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- BAMBURGH CASTLE

- Historic England. "Alnwick Castle (1371308)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 29 November 2007.

- "Staple Island". Farne Islands. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- "Rare sword had 7th Century bling". BBC News. 20 June 2006. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- "Welcome". Bamburgh Research Project. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- "Bamburgh crypt project celebrates area's heritage". Church Times. 29 November 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "Armstrong and Aviation Artefacts Museum". Bamburgh Castle. Archived from the original on 25 March 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- Westwood, Jennifer. "BBC Radio 4 Land Lines - Bamburgh". www.englandinparticular. BBC. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- Black, Joseph (2016). The Broadview Anthology of British Literature: Concise Volume A - Third Edition. Broadview. p. 536. ISBN 978-1554813124.

- "Cornwell's incredible link with Bamburgh". The Journal. 4 October 2005. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- Chandler, Sam (28 September 2018). "All house locations in Forza Horizon 4". Shacknews. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- Huntingtower on IMDb

- "A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court". Times Higher Education. 6 July 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- "A castle fit for a celluloid Queen". The Independent. 25 October 1998. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- "Becket at Bamburgh (1963)". Yorkshire Film Archive. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- "The Devils". Movie Locations. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- "Macbeth". Movie Locations. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- "Mary Queen of Scots". Movie Locations. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- "Newcastle's Castle Keep to pay tribute to 1980s Robin of Sherwood TV series". The Chronicle. 5 September 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- Kirton, Joanne; Young, Graeme (2017). "Excavations at Bamburgh: New Revelations in Light of Recent Investigations at the Core of the Castle Complex". Archaeological Journal. 174: 146–210. doi:10.1080/00665983.2016.1229941.

- "Hollywood stars filming Macbeth at Bamburgh Castle". The Journal. 27 February 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

Sources

- Hope-Taylor, Brian (1977). Yeavering: an Anglo-British centre of early Northumbria. Stationery Office Books. ISBN 978-0116705525.

Further reading

- Dodds, Glen Lyndon (1999). Historic Sites of Northumberland & Newcastle upon Tyne. Albion Press. pp. 33–39. ISBN 978-0952512219.

- Fry, Plantagenet Somerset (1980). The David & Charles Book of Castles. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. pp. 182–183. ISBN 978-0-7153-7976-9.

- Young, Graeme (2003). Bamburgh Castle: The Archaeology of the Fortress of Bamburgh AD 500 to AD 1500. Bamburgh Research Project. ISBN 978-0954648008.