Transport in Buckinghamshire

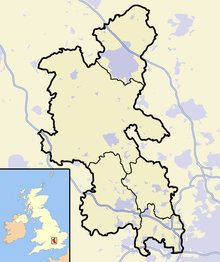

Transport in Buckinghamshire has been shaped by its position within the United Kingdom. Most routes between the UK's two largest cities, London and Birmingham, pass through this county. The county's growing industry (such as in Slough) first brought canals to the area, then railways and then motorways.

Much of Buckinghamshire's transport network can be traced to two ancient roads, the Roman Akeman Street and the Celtic Watling Street. The A41 and A5 roughly follow their paths. In 1838, Buckinghamshire became one of the first counties in England to gain railways, with sections of both the West Coast Main Line[1] and Great Western Main Line[2] opening. These were later followed by other main lines and numerous rural branch lines,[3] many of which closed in the 1930s. The Beeching cuts of the 1960s also closed the Great Central Main Line north of Aylesbury in 1966. The county was also one of the few counties to gain a motorway in the 1950s when the M1 motorway opened its entire section through Buckinghamshire in 1959.[4] Air travel is the only major mode of transport not to have a presence in Buckinghamshire- although Heathrow Airport in Greater London is less than a mile from the southern border of the two counties.

Rail

- This section describes Buckinghamshire as it was prior to 1974.

Origins

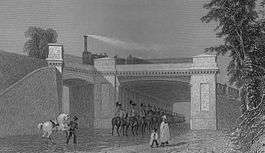

The railway boom of northern England led to the formation of the London and Birmingham Railway (L&BR). In 1833, Robert Stephenson in 1833, planned to meet Joseph Locke's Grand Junction Railway at Birmingham, thus creating a north-south route.[5][6] Though the rail line was initially planned to go through Buckingham, where carriage works would have been built, it was altered to Wolverton due to objections from the Duke of Buckingham. A line to Buckingham would later open in 1850.[7] Construction of the L&BR began in November 1833 and the section from London Euston to Boxmoor in Hertfordshire opened in 1837. The line to Denbigh Hall near Bletchley was completed by the summer of 1838; from there passengers took a stagecoach shuttle to Rugby where the railway continued north.[1] The line through what is now Milton Keynes opened several months later on 17 September 1838.[8][9] Wolverton later became famous as the site of Wolverton railway works which produced rolling stock for over a century—the last new carriage was built there in 1962. The site now houses a supermarket.[9]

At the same time, another railway company, the Great Western Railway (GWR) was formed in 1833, intending to link London with the growing port of Bristol. Isambard Kingdom Brunel was appointed as engineer the same year. Construction began in the mid-1830s.[10] The line from Paddington through Buckinghamshire was opened on 4 June 1838 terminating at Maidenhead Bridge station until Maidenhead Railway Bridge was ready.[11] The line west into Berkshire opened 1 July 1839.[12][13] The line became notable for its use of broad gauge (which was favoured by Brunel) as opposed to standard gauge, which was preferred by most other railway engineers including George and Robert Stephenson. Other railways using standard gauge later met the GWR resulting in the gauge war which the GWR eventually lost. The section through Bucks had a third rail laid on 1 October 1861 allowing both standard and broad gauge trains to run. The broad gauge was removed throughout the country in 1892. The line through Buckinghamshire was quadrupled in late 19th century.[13]

In 1839, a branch line opened from Cheddington on the L&BR to Aylesbury, the county town of Buckinghamshire to transport goods, particularly the Aylesbury Duck, to London.[15] This however required a change at Cheddington, as the line was built connecting north towards Bletchley.[16] The Aylesbury Railway, or Cheddington to Aylesbury Line was independent but operated by the L&BR up to 1846, when the L&BR and two other railway companies merged to form the London and North Western Railway (LNWR). From then onwards, the line was owned by the LNWR.[17]

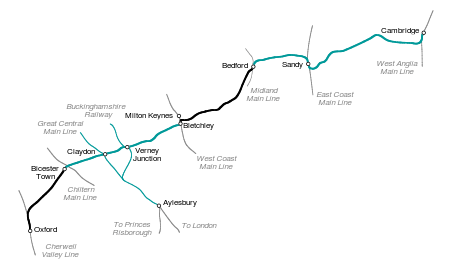

The next line to open was the Bedford and Bletchley Railway on 17 November 1846; it ran from Bedford railway station to the London and Birmingham Railway at Bletchley,[18][19] changing Bletchley from a minor rural backwater to an important junction town. That company merged with the Buckingham and Brackley Junction Railway in 1847 to form the Buckinghamshire Railway, which opened a branch line in 1850 to Banbury. A junction was formed in 1851 at Verney Junction for another new line from there to Oxford,[19] to form what became known as the Varsity Line between Oxford and Cambridge via Bletchley. The Buckinghamshire Railway was worked by the LNWR from July 1851 on, and it was later absorbed by the LNWR in 1879.[20]

In July 1846, the Wycombe Railway was incorporated by an Act of Parliament, allowing the construction of a branch line from Maidenhead, in Berkshire on the GWR to High Wycombe, a major furniture producing town. Construction began in 1852 and was completed two years later in 1854. Building works included a new bridge over the Thames; the Bourne End Railway Bridge was wooden when first built, but replaced by an iron truss bridge in 1895.[21] The line was single track and used the broad-gauge.[22] The Wycombe Railway was extended in 1862 to Thame with another branch from Princes Risborough to Aylesbury in 1863.[A 1][23] The line to Oxford was completed a year later in 1864. The Wycombe Railway was leased to the Great Western Railway, and was bought by the GWR in 1867. The line was converted to standard gauge in 1870.[23]

Two lines serving Windsor in Berkshire opened in 1849- both competing for traffic from the Royalty and tourists. The Windsor, Staines and South Western Railway was authorised in 1847, the Staines to Windsor Line opening its first section from Staines in Surrey to Datchet in Buckinghamshire on 22 August 1848. Due to opposition from both Windsor Castle and Eton College, the line into Windsor was delayed- the line into Windsor & Eton Riverside opened on 1 December 1849.[24] The Windsor, Staines and South Western Railway was absorbed by the London and South Western Railway (LSWR) in 1848.[24] In the same year, 1849, the Slough to Windsor & Eton Line opened from Slough in Buckinghamshire to Windsor & Eton Central again receiving opposition from Eton College. Originally laid as broad-gauge, dual gauge, allowing standard and broad gauge trains to run was laid in 1862.[25] For a brief period between 1883 and 1885, the District Railway ran services between London and Windsor & Eton Central via Ealing Broadway over the GWR tracks from Slough.[26]

The Aylesbury and Buckingham Railway was formed next in August 1860 to build a line between Aylesbury[A 2] and Verney Junction on the LNWR's Varsity Line. It opened in 1868 but trains never ran to Buckingham - even though Verney Junction had a connection to Banbury via Buckingham.[27][28] From 1871, services to Waddesdon Road operated over the Brill Tramway began. Known initially as the Wooton Tramway, it was built primarily for the use of the Third Duke of Buckingham and extended to Brill in 1872, terminating quite a distance from the village itself.[29][30]

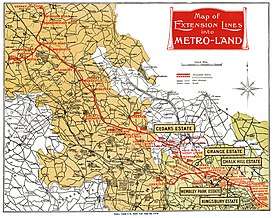

Metroland

The Metropolitan Railway had been the first underground mass-transit railway system in the world when it opened in 1863.[31] In 1868 the Metropolitan and St John's Wood Railway opened a branch from Baker Street to Swiss Cottage, that company being taken over by the Metropolitan Railway in 1879.[31] The line was extended several times from then onwards. The line first entered Buckinghamshire on 8 July 1889 to Chesham[32] but further extension into the Chiltern Hills took place via Amersham in 1892, turning the Chesham route into a branch line.[32] The extension of 1892 terminated at the GWR station in Aylesbury which had opened in 1863.[33]

The Metropolitan Railway was now stretching deep into Buckinghamshire, over land termed Metroland by the Met itself in 1915.[32] In 1891, the Metropolitan had absorbed the Aylesbury & Buckingham Railway which had run from Aylesbury to Verney Junction. On 1 January 1894, the Metropolitan Railway was extended over the A&BR to Verney Junction meeting the LNWR owned Varsity Line which had opened in 1850.[34] The Metropolitan Railway (popularly called the 'Met') thus ran express services from central London to Verney Junction, in the middle of rural Buckinghamshire- a testament to this being that the terminus was so rural that the station was named after the local landowner, Sir Harry Verney.[35] The Met's final extension in Buckinghamshire was over the Brill Tramway which was absorbed on 1 December 1899, almost fifty miles out of central London.[34] Indeed, the extent of the Metropolitan line was so great that for many years the line could not be accommodated into the London Underground Tube map.[36]

The last main line

The next railway which was to weave its way through Buckinghamshire was the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway (MS&LR) which had formed a network of railways in the north of England. In 1897, it changed its name to become the Great Central Railway in anticipation of its London extension.[37] The MS&LR had been a modest company, until Sir Edward Watkin became general manager in 1854.[38] His ambition was to build a rail tunnel under the English Channel in which his trains would run. He was determined to build a line south to London and the South Coast- to do this he became chairman of both the South Eastern Railway which ran between London and Dover and the Metropolitan Railway. Both companies were of use to Watkin as they provided a clear route between Dover and the already existing MS&LR near Nottingham.[38]

The London Extension was planned to European standards and had virtually no sharp corners or steep inclines. There was to be no level crossings- everything was carried above or below the railway.[39] Work began in 1894 still under the MS&LR name. The estimated coast was approximately £3 million and would take four years to complete; the project being in two halves, the southern section running from Rugby in Warwickshire to Quainton Road which was the Metropolitan Railway's junction for Brill and Verney Junction. From there, trains would share tracks with the Met to a new terminus at Marylebone in London.[39] The line officially opened on 9 March 1899, although the first passenger service did not run until 16 March.[38][39][40][41]

Road

Buckinghamshire's road network is still largely composed of single carriageway roads, with a few exceptions. The M40 and M1 motorways both pass through the county on their routes from London to the north, serving High Wycombe and Milton Keynes respectively. The A41 connects Oxfordshire to London through Buckinghamshire. Between Aylesbury and London this road is a grade-separated dual carriageway, essentially a motorway but with more curves and no hard shoulder. Aylesbury is the focal point of Buckinghamshire's road network; the A413, A418, A41 and A4010 roads all converge on the town. However all enter the town as single carriageways and none has a bypass. Consequently, Aylesbury suffers from serious traffic congestion problems during peak hours.

Similarly to Aylesbury, High Wycombe is a nexus of major roads in the southern part of the county. The A4010 from Aylesbury meets the A404 from Amersham as well as the M40 motorway, which passes the town to the south. The A404 continues south beyond the M40 towards Maidenhead.

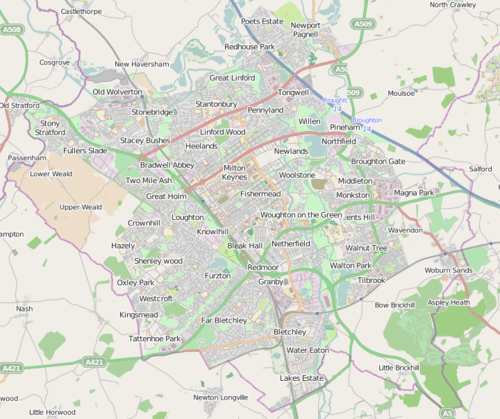

Unlike the other two towns, Milton Keynes, being a new town, has a pre-planned network of roads known as the Milton Keynes grid road system. It is linked to Leighton Buzzard and Aylesbury by the dual carriageway A4146 which opened in September 2007. The single carriageway A508 connects it to Northampton whilst the A421 connects it, via the M1, to Bedford. West of Milton Keynes the A421 meets the A413 in Buckingham, which is also on the A422 road to Banbury.

Buckinghamshire (including Milton Keynes) is served by four motorways, although two are on its borders:

- M40 motorway - cuts through the south of the county serving towns such as High Wycombe and Beaconsfield

- M1 motorway - serves Milton Keynes in the north

- M25 motorway - passes into Bucks but has only one junction (J16-interchange for the M40)

- M4 motorway - passes through the very south of the county with only J7 in Bucks

Also the A41 (former A41 (M)) comes into Buckinghamshire from the east to Aston Clinton.

Four important A roads also enter the county (from north to south):

- A5 - serves Milton Keynes

- A41 - cuts through the centre of the county, serving Aylesbury

- A40 - parallels M40 through south Bucks and continues to central London

- A4 - serves Taplow in the very south

Road travel east–west is good in the county because of the commuter routes leaving London for the rest of the country. There are no major roads that run directly between the south and north of the county (e.g. between High Wycombe and Milton Keynes).

Waterway

The Grand Union Canal runs through the county from Milton Keynes down to Marsworth, passing in and out of Bedfordshire on the way. After this it leaves and enters Hertfordshire. At Marsworth two branches separated, one to Aylesbury and one to Wendover. The Aylesbury branch remains active to this day, whilst the Wendover arm was closed over a century ago. However it is now being restored by a volunteer trust who have reopened it as far as Little Tring. It is presently being restored back to Aston Clinton (see trust website). Another branch which is the subject of restoration efforts is the branch to Buckingham. This left the canal at Cosgrove in Northamptonshire, just north of Milton Keynes. Almost the entire formation is now disused, and the A5 dual carriageway has severed the route.

Notes

- There was no connection to the LNWR station at Aylesbury High Street railway station

- The current GWR Aylesbury station, not the LNWR Aylesbury High Street

References

- "London and Birmingham railway" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 January 2007. Retrieved 31 January 2008.

- "Great Western history, 1835-1892". Retrieved 31 January 2008.

- "Buckinghamshire rail routes". Archived from the original on 15 December 2007. Retrieved 31 January 2008.

- "Motorway Database (M1)". Retrieved 31 January 2008.

-

- Wade-Matthews, Max, ed. (1999). The World's Great Railway Journeys. Oxford: Sebastian Kelly. p. 70. ISBN 1-84081-126-9.

- "London and Birmingham Railway". Retrieved 31 January 2008.

- Simpson, Bill (1994). Banbury to Verney Junction Branch. Banbury, Oxfordshire: Lamplight Publications. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-899246-00-7.

- "London and Birmingham". Archived from the original on 3 March 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2008.

- "A Short History of Wolverton Works". Retrieved 31 January 2008.

- "Great Western history, 1835 - 1892". Retrieved 31 January 2008.

- "Maidenhead Railway Bridge". Retrieved 31 January 2008.

- MacDermot, E T (1927). History of the Great Western Railway, volume I 1833-1863. London: Great Western Railway. p. 92.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "The Story of the G.W.R." Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- Fellows, Reginald B (1976). Railways to Cambridge, actual and proposed. Oleander Press. ISBN 0-902675-62-1.

- "Aylesbury Ducks". Archived from the original on 4 November 2008. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- Cheddington (Map). Google Maps. 2008. Retrieved January 2009. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - Simpson, Bill (1989). The Aylesbury Railway, the First Branch Line, Cheddington ~ Aylesbury. Oxford Publishing Co. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-86093-438-7.

- The World's Greatest Railway Journeys, p. 84.

- Awdry, Christopher (1990). Encyclopedia of British Railway Companies. Sparkford: Patrick Stephens Ltd. p. 63. ISBN 1-85260-049-7.

- "Banbury to Verney Junction (LNWR)". Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- "Bourne End Railway Bridge". Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- "Local History, The Wycombe Railway Company". Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- "The Wycombe Railway". Archived from the original on 23 December 2009. Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- "The Railways at Windsor". The Royal Windsor Web Site. Retrieved 15 July 2007.

- "Windsor Branch workings in the Postwar Years, abstracts from Great Western Railway Journal Volume 4". Retrieved 10 January 2009.

- "Clive's UndergrounD Line Guides, District Line". Retrieved 10 January 2009.

- "Clive's UndergrounD Line Guides, Metropolitan Line". Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- "VERNEY JUNCTION". Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- "QUAINTON ROAD TO BRILL (Wotton Tramway)". Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- Jones, K. (1974). The Wotton Tramway (Brill Branch). Lingfield: Oakwood Press. p. 75. ISBN 0-85361-149-1.

- "Metropolitan line facts". Retrieved 10 January 2009.

- Metro-land' by John Betjeman, BBC Television 1973

- Horne, Mike (2003). The Metropolitan Line: An Illustrated History. Capital Transport Publishing. pp. 96. ISBN 1-85414-275-5.

- Demuth, Tim (2004). The Spread of London's Underground. Harrow: Capital Transport Publishing. p. 11. ISBN 1-85414-277-1.

- "Metropolitan - from Quainton Road to Verney Junction". Retrieved 11 January 2009.

- Garland, Ken (1994). Mr Beck's Underground Map. Harrow: Capital Transport Publishing. ISBN 1-85414-168-6.

- "The Transport Archive Timeline, Key Events from 1897". Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- "History, Great Central Railway". Archived from the original on 21 December 2008. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- "London Extension 1899 - 1969". Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- "The Transport Archive Timeline, Key Events from 1899". Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- "Opening to Grouping - 1899 to 1923". Retrieved 12 January 2009.

Further reading

- Foxell, Clive (2010). The Metropolitan Line. History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-5396-5.