Chesham branch

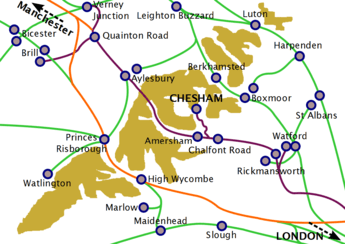

The Chesham branch is a single-track railway branch line in Buckinghamshire, England, owned and operated by the London Underground. It runs from a junction at Chalfont & Latimer station on the Metropolitan line for 3.89 miles (6.26 km) northwest to Chesham. The line was built as part of Edward Watkin's scheme to turn his Metropolitan Railway (MR) into a direct rail route between London and Manchester, and it was envisaged initially that a station outside Chesham would be an intermediate stop on a through route running north to connect with the London and North Western Railway (LNWR). Deteriorating relations between the MR and LNWR led to the MR instead expanding to the northwest via Aylesbury, and the scheme to connect with the LNWR was abandoned. By this time much of the land needed for the section of line as far as Chesham had been bought. As Chesham was at the time the only significant town near the MR's new route, it was decided to build the route only as far as Chesham, and to complete the connection with the LNWR at a future date if it proved desirable. Local residents were unhappy at the proposed station site outside Chesham, and a public subscription raised the necessary additional funds to extend the railway into the centre of the town. The Chesham branch opened in 1889.

| Chesham branch | |

|---|---|

The sharply curved embankment into Chesham station and the entrance to the disused second platform | |

| Overview | |

| Type | Rapid transit |

| System | London Underground |

| Status | Operational |

| Locale | Buckinghamshire, England |

| Termini | Chalfont & Latimer Chesham |

| Stations | 2 |

| Ridership | 427,000 per annum (2009)[1] |

| Operation | |

| Opened | 8 July 1889 |

| Owner | 1889–1933 Metropolitan Railway 1933–1948 London Passenger Transport Board 1948–1963 London Transport Executive 1963–1970 London Transport Board 1970–1984 London Transport Executive 1984–2000 London Regional Transport 2000–present Transport for London |

| Character | Rural rapid transit |

| Depot(s) | Neasden[2] |

| Rolling stock | London Underground S Stock |

| Technical | |

| Line length | 3.89 miles (6.26 km)[3] |

| Number of tracks | 1 |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Electrification | Fourth rail 630 V DC |

While construction of the Chesham line was underway, the Metropolitan Railway was also expanding to the northwest, and in 1892 the extension to Aylesbury and on to Verney Junction opened. Most trains on the branch line were operating as a shuttle service between Chesham and the main line at Little Chalfont rather than as through trains to London. The opening in 1899 of the Great Central Railway at Marylebone station, Edward Watkin's connection between London and Manchester, as well as the highly successful Metro-land campaign encouraging Londoners to move to the rural areas served by the railway, led to an increase in traffic in the area, although the Chesham branch was less affected by development than most other areas served by the railway. In 1933 the Metropolitan Railway was taken into public ownership and became the Metropolitan line of the London Underground. London Underground aimed to concentrate on their core business of passenger transport in London, and saw the rural and freight lines in Buckinghamshire as an expensive anomaly. The day-to-day operation of the Chesham branch was transferred to the London and North Eastern Railway, although London Transport retained control. In 1960 the line was electrified, and from 1962 on was operated by London Underground A Stock trains.

In the 1970s and 1980s decaying infrastructure and the withdrawal of subsidies brought the future of the line into doubt. As one of its last acts the Greater London Council paid for the replacement of two bridges on the line, allowing operations to continue. The centenary of the line in 1989 saw a renewal of interest and an upgrading of the trains between London Marylebone station and Chalfont & Latimer made commuting more practical, and usage of the line stabilised. The introduction of London Underground S Stock in 2010 led to the replacement of the shuttle service with half-hourly through trains to and from London.

Background

The English county of Buckinghamshire is bisected by the Chiltern Hills, which rise sharply and cross the county from northeast to southwest.[4] Although the fertile soil and good drainage of the Chilterns provides ideal conditions for farming, the steep hills historically made travelling difficult. Few sizeable settlements developed in Buckinghamshire, and what roads existed were of poor quality.[4]

The county town of Aylesbury, immediately north of the Chilterns and 37 miles (60 km) from the City of London, was an important agricultural centre. As London grew, the significance of Buckinghamshire as a provider of food increased, particularly following the development of the Aylesbury duck in the 18th century. Large numbers of horses, cattle and Aylesbury ducks were herded along the roads to London's huge livestock market at Smithfield.[5] The strain placed on the roads by bulk livestock movements led to the introduction of a network of high quality toll roads in the area in the 18th century.[5][note 1] The roads crossing the Chilterns followed the valley of the River Misbourne through Amersham or the River Bulbourne through Berkhamsted. These roads greatly improved travel in the area, reducing the journey time from Aylesbury to Oxford or London to a single day.[5]

Between 1793 and 1800 the Grand Junction Canal was built, connecting London to the Midlands. The canal followed the course of the River Bulbourne through the Chilterns, and included a branch to Aylesbury.[5] For the first time the coal and industrial products of northern England and London could be cheaply supplied to Buckinghamshire, and grain and timber from Buckinghamshire's farms could easily be shipped to market.[6] The route taken by the Grand Junction Canal ran through the east of the county, leaving the Chiltern towns of southern Buckinghamshire isolated. When Robert Stephenson's London and Birmingham Railway opened in 1838 it paralleled the route of the canal through Buckinghamshire. Although the short 1839 Aylesbury Railway linked Aylesbury to the London and Birmingham Railway, the rest of central Buckinghamshire remained unconnected to the railway and canal networks.[7]

Early Chesham railway schemes

The Chiltern market town of Chesham /ˈtʃɛsəm/ had historically been an important manufacturing centre. In 1853 the town held three flour mills, three sawmills, three breweries, two paper mills and a silk mill, while of the town's 6,000 inhabitants 30 were recognised as master manufacturers.[7] However, the local economy suffered badly from a lack of connections to the new transport networks. In the 1840s coal cost almost three times more to buy in Chesham than to buy in Berkhamsted,[8][note 3] and it took over 21⁄2 hours for passengers to travel by road from Chesham to the most convenient railway station at Watford.[7]

Between 1845, the height of the railway bubble, and the 1880s numerous schemes were put forward for railways to Chesham. The most significant was an 1845 scheme for an orbital railway bypassing London to connect the railways entering London from the north, west and south; this route was to pass through Chesham.[9][10] The scheme was abandoned,[10] as was an 1853 proposal by railway entrepreneur and former Member of Parliament for Buckingham Harry Verney for a railway line from Watford to Wendover via Rickmansworth and Amersham (around two miles (3 km) from Chesham).[11] Robert Grosvenor, 1st Baron Ebury, whose Watford and Rickmansworth Railway had opened in 1862, proposed extensions from Rickmansworth to Chesham and Aylesbury, but failed to attract funding and abandoned the scheme.[12][13] To the north of Chesham, the London and North Western Railway (LNWR) promoted a railway link between the Great Northern Railway station at Harpenden and the LNWR's station at Boxmoor, which would run on to terminate at Chesham.[14] The LNWR baulked at the cost of the earthworks necessary to reach Chesham and the southern stage of the proposal was abandoned; the line between Harpenden and Boxmoor eventually opened in 1877.[15] (The Harpenden–Boxmoor section was never completed; trains to Boxmoor terminated nearby at Heath Park Halt, and passengers to and from Boxmoor had to complete their journey by horse or horse-drawn bus.[15]) In 1887 a 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) tramway was proposed, which was to run through the streets of Chesham and on to Boxmoor, but the proposal was abandoned owing to a lack of funds and opposition from the operators of toll roads around Boxmoor.[15][16][note 4]

Metropolitan Railway Chiltern schemes

In 1837 Euston railway station opened, the first railway station connecting London with the industrial heartlands of the West Midlands and Lancashire.[17] Railways were banned by a Parliamentary commission from operating in London itself, and thus the station was built on what was then the northern boundary of the city.[18] Other main line termini north of London soon followed at Paddington (1838), Bishopsgate (1840), Fenchurch Street (1841), King's Cross (1852) and St Pancras (1868). All were built outside the built-up area of the city, making them inconvenient to reach.[18][note 5] Charles Pearson (1793–1862) had proposed the idea of an underground railway connecting the City of London with the relatively distant London main line rail termini in around 1840.[19] In 1854 to promote the scheme he commissioned the first ever traffic survey, determining that each day 200,000 walked into the City of London, 44,000 travelled by omnibus, and 26,000 travelled in private carriages.[21] A Parliamentary Commission backed Pearson's proposal over other schemes.[21]

Despite concerns about vibrations causing subsidence of nearby buildings,[22] the problems of compensating the many thousands of people whose homes were destroyed during the digging of the tunnel,[23] and fears that the tunnelling might accidentally break through into Hell,[24][note 6] construction began in 1860.[25] The new railway was built beneath the existing New Road, running from the Great Western Railway's terminus at Paddington to Farringdon and the meat market of Smithfield.[26] On 9 January 1863 the line opened as the Metropolitan Railway (MR), the world's first underground passenger railway.[27] The MR was successful and grew steadily, extending its own services and acquiring other local railways in the areas north and west of London.[28]

In 1872 Edward Watkin (1819–1901) was appointed as the Metropolitan Railway's Chairman.[29] A director of many railway companies, he had a vision of unifying a string of railway companies to create a single route running from Manchester via London to an intended Channel Tunnel and on to France.[30][note 7] In 1873 Watkin entered negotiations to take control of the Aylesbury and Buckingham Railway and a section of the former Buckinghamshire Railway running north from Verney Junction to Buckingham.[34] He planned to extend the MR north from London to Aylesbury to join the existing lines and create a direct route from London to the north of England.[34] He also proposed to extend a short rail branch which ran from the Aylesbury and Buckingham Railway to the small town of Brill, known as the Brill Tramway, southwest to Oxford, and thus create a through route from London to Oxford.[34] Rail services between Oxford and London at this time were poor, and although still an extremely roundabout route, had the scheme been completed it would have formed the shortest route from London to Oxford, Aylesbury, Buckingham and Stratford upon Avon.[35] The Duke of Buckingham, chairman of the Aylesbury and Buckingham Railway and owner of the Brill Tramway, was enthusiastic, and authorisation for the scheme was sought from Parliament. Parliament did not share the enthusiasm of Watkin and the Duke, and in 1875 the Buckinghamshire and Northamptonshire Union Railway Bill was rejected.[35]

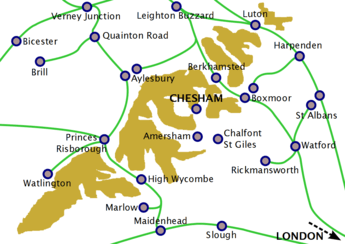

Watkin did, however, obtain consent to extend the MR to Harrow, roughly 12 miles (19 km) northwest of London, an extension which opened in 1880.[36] The Harrow line was further extended to Rickmansworth in 1887.[37] Rickmansworth at this time was a small town with a population of only 1,800; to generate passenger traffic for the new station, a horse bus service between Chesham and Rickmansworth opened on 1 September 1887.[37]

1885 LNWR junction scheme

Watkin continued to harbour ambitions of linking his railway companies in the north and south of England, and while the construction of the Rickmansworth extension was underway planned two possible routes north from Rickmansworth across the Chilterns.[38] One proposal envisaged the MR taking over or reaching agreement with the Aylesbury and Buckingham Railway, building a link between Rickmansworth and Aylesbury, and running over the A&B's line to the north. The A&B had close relations with the Great Western Railway, with whom they shared a station at Aylesbury. Watkin felt it possible that the A&B would reach agreement with the GWR instead and not cooperate with the MR.[38]

In anticipation of the A&B refusing to cooperate, a tentative agreement was reached with the London and North Western Railway, with whom Watkin was on good terms, for the MR to build a route via Chesham to connect to LNWR mainline.[39] This scheme would provide the LNWR with an alternative route into London when necessary, while providing Watkin with his long-sought connection to the north.[38] The land required for an intermediate station near Chalfont St Giles and a line between there and a site outside Chesham was purchased.[38] Agreement was reached with the LNWR that the costs of building the line would be shared equally by the MR and LNWR in return for the LNWR having running rights to Rickmansworth, and an Act of Parliament authorising the extension was obtained in 1885.[40]

After the Act of Parliament had been granted, membership of the board of the LNWR changed, and they abandoned their support for the extension.[40] By this time, the MR had bought most of the land between Rickmansworth and Chesham required for that section of the route.[40]

1888 Aylesbury extension scheme

With relations between the MR and the LNWR deteriorating, Watkin turned his attention to the proposal to link to Aylesbury. Negotiations between the A&B and the GWR had broken down, and Watkin seized an opportunity to agree running rights over the A&B's route north from Aylesbury, taking over the line completely in 1891.[40] In 1888 work began on the extension to Aylesbury.[40]

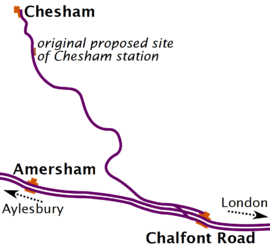

While the route to the LNWR via Chesham had been abandoned, much of the land needed for the section south of Chesham had already been bought. As Chesham, with a population in 1882 of 6,500,[38] was the most significant town in the area through which the MR was building, the MR decided to build the section of line between Chalfont and Chesham as a branch line despite Chesham no longer being on the proposed through route to the north.[40][41] The planned route to the LNWR would have passed to the east of Chesham, and the proposed site of the station was in Millfields, southwest of the town. (Although the extension to the LNWR was abandoned, the MR continued to buy land between Chesham and Tring for some years afterwards, in anticipation of the scheme being revived.[40])

Although work had begun on the Millfields station, including the completion of the station hotel (now the Unicorn pub),[42] the population of Chesham were unhappy at the station being built such a distance from the town.[43] With the extension to meet the LNWR abandoned the railway no longer needed to curve away from the town, and a public subscription raised £2,000 fund a 71-chain (1,562-yd; 1,428 m) extension to a site near the town centre.[44][45] Construction of the branch to Chesham began in late 1887.[40]

Construction and opening

The extensions from Rickmansworth to Aylesbury and Chesham were designed by Charles Liddell and built by contractor James Firbank.[46] Rather than follow the valley of the River Chess, which would have been the most convenient route to Chesham, the route out of Rickmansworth was intentionally built on higher ground to reduce the steep climb over the Chilterns towards Aylesbury,[13][46] and thus rose steadily from Rickmansworth to a hilltop station at Amersham.[47] At Chalfont Road station (renamed Chalfont & Latimer in 1915) the line to Chesham split from the line to Aylesbury. With a total length of 3 miles 56 chains (3 mi 1,232 yd; 5,955 m), the single-track Chesham branch ran alongside the Aylesbury line for a short distance, before curving down the slope of the Chess Valley at a gradient of around 1 in 66.[46] Chalk from the railway's cutting along the Chess Valley was used to build an embankment to bring the railway into the town centre.[46] Bridging the watercress beds of the Chess Valley proved problematic, and the cost of the line exceeded its estimate.[48] Additional costs were incurred by the laying of temporary track in early 1889 to allow the directors of the MR a trial trip along the route.[48]

On 15 May 1889 a demonstration train comprising two carriages and two locomotives ran along the newly completed line from Chesham to Rickmansworth, carrying the subscribers who had funded the extension and representatives of the local authorities and School Boards covering the areas through which the new line ran.[49] (As no Metropolitan Railway train had yet run through to Chesham on the finished line, the train from Chesham to Rickmansworth was drawn by two locomotives belonging to the contractors who had built the line, rather than by MR engines. A third engine ran ahead of the demonstration train to act as a pilot.[50]) A second train carried the directors of the Metropolitan Railway from London to Rickmansworth, collected those passengers who had ridden the demonstration train from Chesham to Rickmansworth, and continued to Chesham.[50]

As the line had not yet formally been approved for opening by the Railway Inspectorate, the MR requested that the local authorities not celebrate the event.[48] However, public interest was high and schools closed for the day. Large crowds gathered around the station and along the line,[48] and a banner reading "Long looked for, come at last" was hung across Chesham station.[50] As the train pulled into Chesham, it was greeted by celebratory gunfire as it drew into the town, and a band at the station played See the Conquering Hero Comes.[50] The party alighted at the newly built Chesham goods depot, which had been decorated as a banqueting hall for the occasion,[50] and an opening ceremony was conducted outside by Edward Watkin and local dignitary and railway financier Ferdinand de Rothschild before the group entered the goods depot for a celebratory meal.[51] Watkin gave a speech recollecting George Stephenson's desire, fifty years earlier, to see the first mainline railway built along the route now being taken by the Metropolitan Railway, joked that he hoped the easy access to London would not lead to the rural nature of the area being displaced by "a sudden influx of cockneys", and spoke of his desire to see the connection northwards to the LNWR completed.[52]

The line was formally inspected by the Railway Inspectorate on 1 July 1889, and the first official service on the line left Chesham for London's Baker Street at 6.55 am on 8 July 1889.[53] Throughout the day large crowds flocked to Chesham station to watch the trains, and the arrival and departure of each train at Chesham was greeted with peals of the bells of St. Mary's Church.[54] Over the course of the day 1,500 passengers travelled on the line, and 4,300 used the line in its first week of operations.[55][note 8]

Following the opening of the line, 17 trains per weekday ran in each direction at intervals of one hour from around 7 am to around 11 pm.[56] The initial trains were drawn by Metropolitan Railway A and B Class locomotives.[53] Most trains stopped at all stations, but a fast trains each morning ran between Chesham and Baker Street, taking 50 minutes from start to finish.[56] On Sundays, trains again ran at hourly intervals, but only 12 trains per day ran and there was a three-hour gap in services in the morning to allow the railway's staff to attend church.[56]

The opening of the railway dramatically ended Chesham's isolation. Commuting to London became possible for the first time, as did affordable excursions to the seaside resorts on the south and east coasts.[55][note 9] The products of the area's industries and farms could for the first time be shipped cheaply to the markets of London, and London newspapers arrived each morning at 7.28 am, in time for delivery.[55]

Stations

The station at Chalfont Road was built with almost all facilities on the up side (the London-bound platform). As Chalfont St Giles, the largest nearby settlement, was on the other side of the tracks, most passengers travelling to and from the station were obliged to take a lengthy detour from the single exit. A footpath across the tracks was added in 1925, but an approach road giving access to the station from the southern side of the railway line was not built until 1933.[57] The station had three platforms; one platform in each direction on the London–Aylesbury line, and a bay platform alongside the up platform for trains to Chesham.[57] A run-around loop was built to allow locomotives reversing in the bay platform always to be at the front of their trains. It was built outside the station, meaning locomotives reversing on the Chesham line were obliged to push their trains out of the station before performing the manoeuvre.[57]

The station was renamed "Chalfont & Latimer" in 1915,[58] although station signage was inconsistent and on absorption by London Transport in 1933 its roundel signs read simply "Chalfont".[59] Increased passenger numbers strained the station's minimal facilities, and it was eventually redeveloped with extended shelters and improved waiting rooms in 1927.[60] The platforms were extended during the electrification works of 1957–60.[61]

The Metropolitan Railway Act 1885 had given Watkin permission to extend the line from Chesham to connect with the LNWR at Tring.[62][63] Thus, although it was the terminus of the line, Chesham station was designed with a revival of the LNWR extension scheme in mind. The small station building was set to one side of the tracks to allow for a possible extension onwards.[48] The station had a single platform, with a run-around loop and turntable alongside, together with a coaling station and water tank.[57][note 10] The station was lit by gas light until 1925; the local gas works, which consumed around 5,000 tons of coal each year,[65] threatened to withdraw their coal traffic from the line if the station were fitted with electric lighting.[60] While Chalfont Road station initially served a sparsely populated rural area (the village of Little Chalfont had not yet grown around the station), Chesham station was busy, and at the time of its opening had a full staff of a stationmaster, two ticket inspectors, two clerks, two porters and two collectors.[56]

Chesham also had extensive goods facilities, particularly for coal; the goods yard was initially equipped with a mobile 5-ton crane, replaced by a fixed 8-ton crane between 1898–1900.[60] The outward transport of watercress, a major local industry, also generated significant traffic.[60] During the electrification of the line in 1957–60 the station was equipped with a bay platform for passenger trains, to allow it to accommodate both through services to and from Baker Street and the Chalfont & Latimer–Chesham shuttle simultaneously.[61] This bay platform was closed on 29 November 1970 and is now a garden.[66]

The Metropolitan Railway's passenger coaches, dating from 1870 and designed for underground use within London, were not fitted with heating until 1895. Consequently, both stations were also equipped with equipment for heating footwarmers, which would be distributed to passengers during cold weather.[67]

Opening of the Aylesbury line

As developments on the line from Chalfont Road to Chesham took place, progress continued on the 16-mile (26 km) cross-Chiltern link between Chalfont and Aylesbury.[64] On 1 September 1892 work was completed as far as a temporary station south of Aylesbury.[56] (The connection with the Aylesbury and Buckingham Railway—absorbed by the Metropolitan Railway in 1891—was completed in late 1893. From 1 January 1894 MR trains used the A&BR's Aylesbury station, and the temporary station was abandoned.[68]) The line to Chesham became a branch line, generally operated by a shuttle service between Chalfont Road and Chesham, although some trains at peak periods continued to run between London and Chesham.[64] The MR had bought a number of Metropolitan Railway C Class locomotives to replace the ageing A and B class engines, but these performed poorly on the London-Aylesbury line and were soon replaced by the Metropolitan Railway D Class. As a consequence, the C class engines were often used on the Chesham shuttle services.[64]

While construction of the Chesham and Aylesbury lines was underway Watkin continued to press for the extension from Chesham to the LNWR, as did prominent manufacturers in Chesham.[63] However, construction of the extensions had left the MR seriously exposed financially, forcing the board to cut dividends in July 1889.[63] At a Special General Meeting on 12 February 1890 matters came to a head. Shareholders endorsed the decision to acquire the Aylesbury and Buckingham Railway and authorised the MR to acquire the moribund Brill Tramway, which connected with the A&BR at Quainton Road station, but blocked the expensive extension beyond Chesham, as well as Watkin's proposed extension to Moreton Pinkney to the north.[63] (Watkin's Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway was refused consent at the time to build south to connect with the MR at Moreton Pinkney, which would have rendered the Moreton Pinkney branch an inevitably loss-making branch line serving a very lightly populated area. Watkin was determined to build this section as a vital segment in his vision of a London–Manchester railway, and proposed that if the MR would not build this section, the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway would build the line themselves and lease it to the MR. The MR board refused to have anything to do with the scheme. Moreton Pinkney was eventually served by Watkin's railway network in 1899 as Culworth railway station on the Great Central Railway.[69])

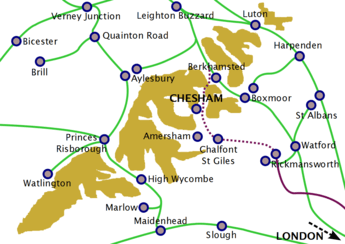

In 1894 Edward Watkin suffered a stroke. Although he nominally remained a director of his railway companies, he resigned all his railway chairmanships and his influence was effectively ended.[70] With the connection at Aylesbury complete, the Metropolitan Railway reached 50 miles (80 km) northwest of London, and his planned route between London and northern England was almost complete. Watkin's Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway continued to build southwards from its southernmost point at Annesley, reaching Quainton Road station on the former A&BR in 1899 and completing the north–south link, the Great Central Railway (GCR),[71][72] in time for Watkin to see his vision completed before his death in 1901.[73]

Relations with the Great Central Railway

After Watkin's retirement from management, relations between the MR and GCR deteriorated rapidly over shared use of Baker Street station and the congested route into London, and soon broke down completely. On 30 July 1898 John Bell, General Manager of the Metropolitan Railway, took control of the Quainton Road signal box himself and refused to allow a GCR train onto MR-owned tracks on the grounds that it was scheduled to take the Great Western rather than the Metropolitan route south of Aylesbury,[74] while on one occasion in 1901 King Edward VII was travelling home after visiting a friend in Wendover; the MR signalman allowed a slow goods train to run in front of the royal train, causing the King to arrive late back in London.[75] The MR management also refused the GCR permission to install points to connect their engine shed at Aylesbury to the railway line, on the grounds that the land for the shed had been bought clandestinely.[75] Eventually a parallel set of tracks was built for the GCR between Harrow and London, running alongside the MR to a separate terminus at Marylebone, a short distance from Baker Street.[76] The GCR continued to share the less-congested section between Quainton Road and Harrow—including Chalfont Road station—with the MR.[76]

With the hostile Metropolitan Railway controlling the GCR's only approach to London through Quainton Road and Aylesbury, GCR General Manager William Pollitt decided to create a link with the Great Western Railway to create a second route into London which bypassed all MR property.[77] In 1899 the Great Western and Great Central Joint Railway began construction of a new line, commonly known as the Alternative Route, to link the GWR's existing station at Princes Risborough to the new Great Central line. The line ran from Princes Risborough north to meet the Great Central at Grendon Underwood, about three miles (5 km) north of Quainton Road, thus bypassing Quainton Road altogether.[71][78] Although formally an independent company, in practice the new line was operated as a part of the Great Central Railway.[79] The new route opened in 1906,[80] and a substantial part of the GCR's traffic to and from London was diverted onto the Alternative Route, damaging the profitability of the MR's railway operations.[81][note 11]

The MR management were horrified at the potential loss of income and restarted negotiations with the GCR, and a 1906 agreement meant that GCR traffic was shared between the old and new routes.[76] Management of the shared route north of Harrow alternated every five years between the MR and GCR. (A proposed link between Marylebone and the sub-surface section of the Metropolitan Railway, which would have allowed GCR trains to run across London via the MR-controlled Thames Tunnel and on to the south coast, was abandoned.[82]) The sharing arrangement meant through trains running from Chesham to Marylebone, as well as the MR terminus at Baker Street, and that the branch was worked by GCR trains as well as the ageing MR rolling stock.[82]

Chesham and Metro-land

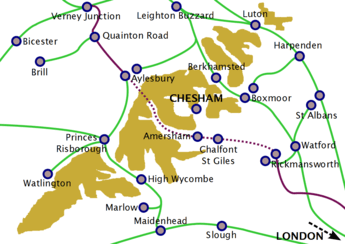

In 1903 Robert Selbie was appointed Secretary of the Metropolitan Railway, working on the electrification of the London sections of the line; by 1905 the route was electrified as far as Harrow, although the sections north of Harrow, including the Chesham branch, continued to be worked by steam power.[83] In 1908 he was appointed General Manager, a position he was to hold until 1930.[83] Selbie realised that Watkin's schemes and the expensive electrification project had left the company with major financial liabilities, and that the MR's core business in central London would come under significant pressure as the use of automobiles increased and as the new Underground Electric Railways of London tube lines improved their services. Selbie set out to reshape the MR as a feeder route for goods and passengers into London.[84]

New branches to Uxbridge, Watford and Stanmore were built, and from 1915 the extremely effective Metro-land advertising campaign began, promoting the lightly developed areas along the MR's routes as ideal for commuting to London.[84][85] Watkin's expansionist schemes had led to the acquisition of huge tracts of near-worthless land in the Buckinghamshire countryside around the MR's routes, as the MR had tried to take control of as much land as possible along every possible route between London and Manchester. With the GCR complete it was no longer necessary for the MR to keep these lands clear for potential railway use, and Selbie began development on a massive scale.[84] By 1939 over 4,600 houses had been built by the MR alone, and entire new towns had grown around the MR's stations between Harrow and Aylesbury. This development not only generated huge amounts of money from property development, but vastly increased use of the railway for passenger and goods traffic.[86] The MR's Baker Street terminus was also redeveloped and a block of 180 luxury apartments known as Chiltern Court was built above the station.[86][87][note 12] With the profits generated, the line was further electrified to Rickmansworth. Again, the Chesham branch was not electrified and remained operated by steam locomotives; the electric locomotives would be uncoupled from their trains at Rickmansworth and a steam locomotive would haul the train to Chesham.[86] By this time, the steam sections of the route were generally worked by the powerful Metropolitan Railway H Class engines, capable of speeds of up to 75 miles per hour (121 km/h).[89]

Selbie also made a conscious effort to attract the wealthy classes to the railway. Stations such as Sandy Lodge (now Moor Park) were built to serve golf courses and hunts along the route, and horse-vans were provided at stations serving hunts and point to points.[88] Two Pullman cars were introduced in 1909 on selected services between the City of London and Chesham, Aylesbury and Verney Junction for the benefit of businessmen travelling to work and theatregoers returning from London.[90][note 13]

Despite the huge population growth in southern Buckinghamshire caused by the railway, Chesham remained relatively unaffected by development. Although there was extensive development in Chesham Bois, roughly halfway between Chesham and Amersham,[92][93] between 1889 and 1925 the population of Chesham itself grew by less than 2,000, and between 1925 and 1935—the peak of the Metro-land boom—by only 225.[94] Between 1921 and 1928 the season ticket revenue from Amersham and Chalfont & Latimer stations rose by 134%; that from Chesham by only 6.7%.[94][note 14] Although the MR owned large tracts of land around Chesham, bought in anticipation of a revival of the LNWR connection scheme, Selbie chose not to build a housing estate on the site, instead selling much of it to the local council.[94] By this time, service on the Chesham branch was of a relatively poor quality. Improvements to the central London section and the prioritisation of the Aylesbury line had led to ageing surplus stock often being used on the Chesham branch, and the partial electrification caused delays at Rickmansworth as steam locomotives were coupled and uncoupled.[94] As the branch was mainly operated as a shuttle service passengers to and from Chesham were obliged to wait at Chalfont & Latimer station. This had been built to serve a lightly populated area, but the Metro-land development had caused a much larger number of users than it had been designed for, and it had few waiting facilities, poor lighting, inadequate shelter, and dirty toilets.[58] As Amersham grew, more and more of the trains which had previously run direct from London to Chesham instead ran to Amersham, causing further crowding as passengers waited for the shuttle service at Chalfont & Latimer.[60] Improving road transport caused an increasing number of commuters to abandon the Chesham line, which in turn prompted the MR to further reduce passenger services.[60]

1909 accidents

Although the short line to Chesham generally had a good safety record, despite its sharp curves and relatively steep gradient, it suffered two significant accidents in this period. On 19 August 1909 the A class engine hauling the 7.53 am train from Chesham broke an axle and derailed outside Chesham. There were no injuries but the track was blocked; a passenger service was maintained by operating shuttle services from each end of the branch to the crash site, where passengers were obliged to walk around the derailed engine to change trains.[95] On 6 November 1909 a backdraught from a locomotive firebox enveloped Robert Prior, the train's driver, in flames.[82] (The type of locomotive is not recorded, but it is likely to have been a Metropolitan Railway D Class, which are known to have had a problem with backdraughts.[82]) The locomotive's fireman managed to drive the train to Chesham, where Prior died from his injuries two days later.[82] An inquest found that Prior had failed to turn on the blower, and a verdict of accidental death was recorded.[82]

London Transport

Robert Selbie had fought vigorously for the independence of the Metropolitan Railway, and had successfully preserved the MR's independence during the grouping of 1923, which had merged almost all of Britain's railways into four companies. However, on 17 May 1930 he died suddenly, and his successors acceded to pressure from the Ministry of Transport to merge with London's other underground railways.[96] On 1 July 1933 the merger brought all of London's underground railways aside from the short Waterloo & City Railway, under public ownership as part of the newly formed London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB). The Metropolitan Railway became the Metropolitan line of the London Underground.[97]

Frank Pick, Managing Director of the Underground Group from 1928 and the Chief Executive of the LPTB, aimed to move the network away from freight services, and to concentrate on the electrification and improvement of the core routes in London.[98] In particular, he saw the lines beyond Aylesbury via Quainton Road to Brill and Verney Junction as having little future as financially viable passenger routes.[99] On 30 November 1935 the last train ran on the Brill Tramway between Brill and Quainton Road,[100] and at the stroke of midnight, the rails connecting the Tramway to the main line were ceremonially severed.[101] The former Aylesbury and Buckingham Railway between Quainton Road and Verney Junction was closed to passengers on 6 July 1936,[102] and London Transport services north of Aylesbury were withdrawn.[102][note 15]

London and North Eastern Railway operation

The route to Aylesbury and the Chesham branch survived Pick's cutbacks to the Metropolitan line, but the former Metropolitan Railway's routes in Buckinghamshire, and in particular the Chesham line, were increasingly regarded as an expensive anomaly by London Transport.[106] After 1937 the operation of all steam services north of Rickmansworth was passed to the London & North Eastern Railway (LNER).[106] The LNER retained Metropolitan Railway E Class locomotives to work the Chesham branch, but other steam services on the former MR were operated by LNER N5 Class locomotives.[107]

The LNER did not want to take full responsibility for the line, and although they provided the services, ownership remained with the LPTB. In 1935 the LPTB, seeking to abandon steam power as much as possible, drew up a scheme to include electrification of the Amersham line as part of the New Works Programme.[107] It was not planned to electrify the Chesham branch; instead, a diesel-powered GWR railcar was borrowed from the GWR for trials on the branch.[107][108] Although the railcar performed well on the curves and slopes of the branch, the railcar had a capacity for only 70 passengers and was only able to haul light amounts of goods.[107] The LPTB commissioned its own, larger, railcar design, but by the end of 1936, it decided instead to electrify the Chesham branch, and the railcar schemes were abandoned.[107][109] The LPTB's plan envisaged electric trains splitting at Chalfont & Latimer, with half of each train continuing to Amersham and half to Chesham.[110]

Although some preparatory work was carried out, the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 brought the electrification north of Rickmansworth to a halt.[111] First class travel was abandoned by the LPTB,[112] along with the Pullman cars,[90] and the line was operated entirely as a shuttle service.[111] In 1940 the Chesham branch was converted to autotrain working, in which the trains could be driven from each end, thus avoiding the time-consuming repositioning of the locomotive.[112][113] LNER C13 Class locomotives were used for this push-pull working, along with two three-car sets of antiquated Ashbury passenger cars dating from 1898.[111]

Nationalisation

On 1 January 1948, almost all railways in Britain—including the London Transport Passenger Board and the London and North Eastern Railway—were nationalised under the Transport Act 1947.[114] The LPTB became the London Transport Executive (LT), and the LNER became a part of British Railways.[114] In the Greater London Plan of 1944 Sir Patrick Abercrombie had strongly recommended a halt to further modern development in Chesham and along the Chess Valley to preserve the sensitive local environment, and there was thus little prospect for growth in passenger numbers on the branch.[115]

For the first decade after nationalisation services to Chesham continued much as before, although the unification of the mainline companies meant a wider variety of locomotives operating services on the branch.[114] For two weeks from 13 October 1952 LT experimented with a three-car lightweight diesel train on the route, but the train used had difficulty negotiating the line's sharp bends and the branch reverted to steam operations.[61][116]

By the mid-1950s, British Railways had begun to operate in regional units, and responsibility for services on the former Great Central routes in the Chilterns was transferred to the London Midland Region. Services on the branch were generally hauled by LMS Ivatt Class locomotives, although passenger trains continued to use the 1898 Ashbury cars.[114] British Railways continued to operate goods services on the branch, although these declined steadily owing to competition from road haulage to the point at which coal deliveries were the only significant business.[117]

By now the pre-war electrification scheme had been revived.[118] In 1957 electrification between Rickmansworth and Amersham and Chesham began.[61] Chalfont & Latimer's platforms were extended and a second platform was opened at Chesham on 3 July 1960 to prevent through operations to and from Baker Street from interfering with the Chesham–Chalfont & Latimer shuttle.[61][119] An electric service using London Underground T Stock began operations between Chesham and Chalfont & Latimer on 16 August 1960, with former MR electric locomotives hauling the through trains to and from London.[66] A steam locomotive was kept on standby in the new second platform at Chesham, in case of a failure of the electric trains.[120] From June 1962 both the T Stock and the locomotive-hauled trains were replaced by the newly introduced London Underground A Stock.[66]

The last scheduled London Transport steam passenger train on the branch left Chesham at 12.11 am on 12 September 1960.[118] 1,917 passengers used the line that day, in comparison with a typical Sunday usage of around 100.[118] Earlier on 11 September descendants of the Chesham residents who had attended Watkin's original meeting to promote the railway, along with 86-year-old Albert Wilcox who had been present at the opening of the line, rode the steam shuttle to Chalfont & Latimer and back, and attended a ceremony in Chesham's Council Chamber.[121] (Although the 12.11 am service from Chesham on 12 September 1960 was the last scheduled London Transport steam service to use the line, a steam train left Marylebone for Chesham each morning at 3.55 am to deliver newspapers, returning as the first passenger train from Chesham at 5.58 am.[122] This journey to Marylebone was open to the public but was unadvertised and did not appear in published timetables.[123] This arrangement continued to be operated by steam locomotive until 18 June 1962.[119]) The Ashbury passenger cars, which by now had each covered around 800,000 miles (1,300,000 km), were retired from service.[118][note 16] The last steam-powered passenger services on the remaining non-electrified section between Amersham and Aylesbury ran on 9 September 1961.[124] The line between Amersham and Aylesbury was handed over to British Rail, leaving Chesham as the westernmost point of the London Underground network.[125] The goods yard at Chesham was closed in 1966,[note 17] and a train hauled by a former GWR 5700 Class locomotive removed the track from the goods yard, the last steam service to use the line.[118] On 17 October 1967 the newspaper train service and its return journey to Marylebone, by this time worked by a British Rail diesel multiple unit, was abandoned, leaving the branch exclusively operated by London Transport trains.[122][note 18]

Closure proposals

Although LT had hoped that the electrification would boost revenue, the Chesham branch generated little income.[66] In a period of recession LT was reluctant to continue subsidising a little-used branch line some distance outside its core area.[66] Fares were drastically increased in 1970, leaving a monthly season ticket from Chesham to Baker Street costing £43 (about £670 in 2020).[126][127] London Transport considered closing the branch, but it survived thanks to subsidies from the Ministry of Transport, Buckinghamshire County Council and the Greater London Council.[128] Sunday services on the branch were abolished as a cost-cutting measure, although this decision was reversed following protests.[129]

In 1982 the future of the Chesham line came into serious question, as it became clear that the two bridges carrying the line into Chesham were deteriorating badly and that, unless the bridges were replaced, the branch could not continue to operate after 1986.[128] By this time rail services in Buckinghamshire had been drastically cut back under the Beeching Axe mass rail closure programme of the 1960s.[130] The last passenger trains north of Aylesbury had run on 5 September 1966,[131][132] The Greater London Council was scheduled for abolition, bringing their subsidy of the Chesham branch to an end.[128] Buckinghamshire County Council was unwilling to pay for replacing the bridges, proposing instead that the station be relocated to the original proposed station site of the 1880s on the south side of the bridges.[128] Safety concerns had led to a speed limit of 15 miles per hour (24 km/h) over the bridges, and the line appeared certain to be closed.[131]

Revival

Although no part of the Chesham branch was in Greater London, the Greater London Council, as one of its last acts, granted £1,180,000 to replace the bridges. New bridges were built alongside the existing bridges to minimise disruption, and were rolled into place on 24 March 1986 and 14 April 1986.[131]

In 1989 the centenary of the branch saw a revival of interest in the line. Over the weekends of 1–2 and 8–9 July special services were run between Watford and Chesham, using two preserved Metropolitan Railway steam locomotives and a former MR electric locomotive.[125][133] The service was a great success, with over 9,000 people travelling on the trains and large numbers of people travelling to the area to watch the trains.[133] The success prompted LT to repeat the Steam on the Met event annually until 2000, although often running to Amersham rather than Chesham.[134]

In the early 1990s the number of passengers using the branch stabilised at about 800 people each weekday.[135] In 2009 the Chesham branch saw 427,000 journeys each year.[1][note 19] The proposal to close the Aylesbury–Marylebone route was dropped, and instead the line was upgraded and equipped with fast British Rail Class 165 trains in the early 1990s. These reduced the travel time between Chalfont & Latimer and Marylebone to 33 minutes, increasing usage of the line as a commuter route.[136] The Chesham branch was proposed as a terminus for the original Crossrail scheme, which would have seen Crossrail trains running from Paddington to serve the stations between Rickmansworth and Aylesbury and the Chesham branch, allowing London Transport to withdraw from Buckinghamshire and cut the Metropolitan line back to serve only the branches to Watford and Uxbridge.[137] The bill proposing the scheme was defeated in Parliament and abandoned in 1995,[136] and the revived scheme authorised by the Crossrail Act 2008 did not include the branches to Aylesbury and Chesham.[138] By this time the little-used Central line branch from Epping to Ongar had closed, with the last services running on 30 September 1994, leaving Chesham—already the westernmost point of the London Underground network since 1961's withdrawal from Aylesbury—as the northernmost point on the London Underground.[139]

By the time London Underground operations were transferred to the newly created Transport for London (TfL) in 2000, the A Stock trains were already 40 years old. The C Stock trains used on the Circle line, Hammersmith & City line and sections of the District line and the D Stock used on the remainder of the District line were also ageing, and no plans were in place for their replacement.[140] Following lengthy and expensive negotiations, an order was placed in 2003 with Bombardier Transportation for a fleet of new trains to take over all operations on the Metropolitan, Hammersmith & City and District lines.[141]

Restoration of full through service

The eight-car configuration of the S Stock design includes open connections between the passenger cars, and thus cannot be split into shorter four-car trains capable of fitting into the bay platform at Chalfont & Latimer station. Consequently, in 2008 TfL announced that the shuttle service was to be abandoned.[142] Instead, the long-standing Metropolitan line service of four trains per hour to and from Amersham was to be reduced to two, with the other two services running as through trains between Aldgate and Chesham.[142] After 118 years of service on 11 December 2010 at 12.37 pm the last Chesham shuttle service left Chesham station. A Stock trains continued to run on the line, providing through services to London, until 29 September 2012 when they were retired and replaced by S8 Stock trains.[143]

Notes and references

Notes

- Historically, the roads of Buckinghamshire had been maintained by their local parishes.[4] The increase in livestock traffic between Aylesbury and London following the development of the Aylesbury duck led to large numbers of people using the road network who did not stop or spend money in the villages along the route, and thus were not contributing directly or indirectly to the maintenance of the roads. Consequently higher quality roads were built on the significant trading routes, maintained by tolls.[5]

- Only significant stations and junctions are marked.

- Coal cost 8d per cwt in Berkhamsted, compared to 1s 2d (22d) per cwt in Chesham.[8]

- The Lowndes family, prominent Chesham landowners, bought a batch of redundant London and Birmingham Railway granite blocks in an effort to encourage construction of the tramway. When the tram scheme was abandoned the blocks were used to support cattle troughs around Chesham. A number of the blocks now serve as benches in Chesham's Lowndes Park.[15]

- The ban on stations in London was firmly enforced, with the exception of Victoria station (1858) and the Snow Hill tunnel of the London, Chatham and Dover Railway (1866).[19] The Snow Hill tunnel (now Thameslink) remains the only main line railway to cross London.[20]

- "The forthcoming end of the world would be hastened by the construction of underground railways burrowing into the infernal regions and thereby disturbing the devil."—from a sermon preached by Dr Cuming at Smithfield, much of which would be destroyed by the building of the Metropolitan Railway, c. 1855[24]

- Authorisation for the Channel Tunnel was gained in both England and France, and work began in 1881.[31] Only 3,896 yards (3,562 m) were dug before the British government ordered a halt to the scheme, owing to concerns about its potential as an invasion route.[32][33]

- In addition to the large number of people using the line on the first day out of curiosity, usage figures for the first week were inflated by a large group of people travelling to a temperance demonstration in London on 9 July. Passenger numbers dropped from 4,300 in the first week to 2,800 in the second.[55]

- Edward Watkin's control of the Southern Railway and the Thames Tunnel made interchange between the Metropolitan Railway routes north of London and the lines south of London to Kent and the English Channel feasible. It was possible to travel from Chesham to Calais and back in a single day.[55]

- The turntable was demanded by the Railway Inspectorate, who were concerned at the potential risks caused by the Metropolitan Railway's early locomotives—which had been designed for underground use and consequently were not fitted with cabs to protect from the weather and had limited visibility to the driver's rear—running bunker-first (e.g., in reverse) along busy rural lines. As the MR expanded in the 19th century, the turntable was relocated so as always to be at the end of the line. Initially installed at Harrow-on-the-Hill station, it was relocated to Rickmansworth and later to Chesham as their respective extensions opened. Improved locomotive designs capable of working safely in either direction, and the fitting of the A and B class trains with protective cabs in 1895,[64] meant that the turntable was little-used by the time the latter two stations opened, and it was removed in 1900.[57]

- Although the diversion of Great Central traffic onto the Alternative Route damaged the Metropolitan Railway's railway income, much of the MR's income came from property development in the areas it served. This division increased in profitability after the opening of the Alternative Route; the housing developments, most of which were situated near the MR's line, increased in value following the reduction in smoke and noise from trains.[81]

- Chiltern Court became one of the most prestigious addresses in London. It was home to, among others, the novelists Arnold Bennett and H. G. Wells.[88] A blue plaque commemorating Wells was added to the building on 8 May 2002.[87] A second block named Chalfont Court was later added to the north of Chiltern Court.[87]

- The Pullman cars, named Mayflower and Galatea, served meals and drinks to passengers.[88] They were also the only vehicles on the Metropolitan Railway and London Underground equipped with toilets.[88] Each carriage carried 19 passengers, who paid a supplement of one shilling to use them.[91] At 60 feet (18 m) long they were the longest rolling stock in use on the Metropolitan Railway system, and the track had to be adjusted in places to allow them to operate.[91] They were withdrawn from service in 1939, and became a timber merchant's office in Hinchley Wood in 1940.[90]

- £4,736 to £11,116 and £4,683 to £4,994, respectively.[94]

- GCR, and later British Rail, passenger trains continued to run on the former A&BR between Aylesbury and Quainton Road until 1963.[103] London Transport services were briefly restored for a short distance north of Aylesbury in 1943 with the extension of the Metropolitan line's London–Aylesbury service to Quainton Road, but this service was once more withdrawn in 1948.[104] The route north from Aylesbury via Quainton Road remains in use by freight trains but has not been served by scheduled passenger trains since 1963.[103][105]

- Four of the six Ashbury cars remain operational on the Bluebell Railway, and a fifth is on display at the London Transport Museum.[118]

- The former goods yard is now the station car park.[118]

- Sources disagree over the withdrawal date of the newspaper train; Foxell (2010) states that it was withdrawn on an unspecified date in 1962,[123] while Mitchell & Smith (2005) give a closure date of 17 October 1967.[122] Photographic evidence confirms that the service was still in operation, worked by a British Rail Class 115, in July 1962.[123]

- 2003: 430,000 journeys; 2004: 429,000 journeys; 2005: 407,000 journeys; 2006: 404,000 journeys; 2007: 432,000 journeys; 2008: 450,000 journeys; 2009: 427,000 journeys. As all journeys on the branch involve Chesham station, the total number of entries and exits at Chesham station can be considered equal to total usage.[1]

References

- "Customer metric: entries and exits 2009: Chesham". London: Transport for London. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- "Key Facts". London: Transport for London. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- "Metropolitan line facts". London: Transport for London. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- Foxell 1996, p. 13.

- Foxell 1996, p. 14.

- Foxell 1996, p. 15.

- Foxell 1996, p. 16.

- Foxell 1996, p. 17.

- Cockman 2006, p. 39.

- Foxell 1996, p. 20.

- Foxell 1996, p. 19.

- Cockman 2006, p. 58.

- Simpson 2004, p. 9.

- Foxell 1996, p. 21.

- Foxell 1996, p. 22.

- Cockman 2006, p. 87.

- Wolmar 2004, p. 13.

- Wolmar 2004, p. 15.

- Wolmar 2004, p. 18.

- Wolmar 2004, p. 63.

- Wolmar 2004, p. 22.

- Wolmar 2004, p. 33.

- Wolmar 2004, p. 29.

- Halliday 2001, p. 7.

- Wolmar 2004, p. 32.

- Foxell 1996, p. 23.

- Wolmar 2004, p. 39.

- Cockman 2006, p. 94.

- Wolmar 2004, p. 76.

- Lee 1935, p. 237.

- Simpson 2003, p. 48.

- Foxell 1996, p. 28.

- Wilson & Spick 1994, pp. 14–21.

- Melton 1984, p. 52.

- Melton 1984, p. 53.

- Foxell 1996, p. 29.

- Foxell 1996, p. 30.

- Foxell 1996, p. 31.

- Simpson 2004, p. 8.

- Foxell 1996, p. 32.

- Simpson 2004, p. 14.

- Foxell 2010, p. 22.

- Simpson 2004, p. 39.

- Foxell 1996, pp. 32–33.

- Oppitz 2000, p. 29.

- Foxell 1996, p. 35.

- Simpson 2004, p. 10.

- Foxell 1996, p. 37.

- Foxell 1996, pp. 37–38.

- Foxell 1996, p. 38.

- Foxell 1996, p. 39.

- Simpson 2004, pp. 39–40.

- Foxell 1996, p. 40.

- Foxell 1996, pp. 40–41.

- Foxell 1996, p. 43.

- Foxell 1996, p. 41.

- Foxell 1996, p. 36.

- Foxell 1996, p. 57.

- Mitchell & Smith 2005, §26.

- Foxell 1996, p. 58.

- Foxell 1996, p. 71.

- Horne 2003, p. 16.

- Cockman 2006, p. 95.

- Foxell 1996, p. 44.

- Mitchell & Smith 2005, §VI.

- Foxell 1996, p. 72.

- Foxell 1996, p. 45.

- Rose, Douglas (1999). The London Underground: A Diagrammatic History (7th ed.). London: Douglas Rose. ISBN 1-85414-219-4.

- Cockman 2006, p. 96.

- Horne 2003, p. 23.

- Melton 1984, p. 71.

- "Great Central Railway: General description of the line and its business". The Economist. London (3521): 316. 18 February 1911.

- Foxell 1996, p. 46.

- Simpson 2004, p. 15.

- Cockman 2006, p. 101.

- Foxell 1996, p. 47.

- Simpson 1985, p. 78.

- "The New Railway System In Middlesex And Bucks". News. The Times (37491). London. 5 September 1904. col D, p. 2. (subscription required)

- Simpson 1985, p. 81.

- Oppitz 2000, p. 11.

- "British Railway Results". The Economist. London (3308): 89. 19 January 1907.

- Foxell 1996, p. 48.

- Foxell 1996, p. 51.

- Foxell 1996, p. 52.

- Cockman 2006, p. 5.

- Foxell 1996, p. 53.

- Horne 2003, p. 37.

- Foxell 1996, p. 54.

- Foxell 1996, p. 55.

- Simpson 2005, p. 22.

- Horne 2003, p. 47.

- Jackson 2006, p. 66.

- Jackson 2006, p. 75.

- Foxell 1996, p. 56.

- Foxell 1996, p. 49.

- Foxell 1996, p. 63.

- Demuth 2003, p. 18.

- Jones 1974, p. 56.

- Foxell 2010, p. 72.

- Melton 1984, p. 74.

- Simpson 1985, p. 84.

- Mitchell & Smith 2006, §iii.

- Mitchell & Smith 2006, §15.

- Simpson 1985, p. 108.

- Moore, Jan (3 May 1990). "All Steamed Up for Grand Gala". Bucks Herald. Aylesbury.

- Foxell 1996, p. 64.

- Foxell 1996, p. 65.

- Foxell 2010, p. 75.

- Foxell 2010, p. 77.

- Horne 2003, p. 63.

- Foxell 1996, p. 66.

- Horne 2003, p. 66.

- Foxell 2010, p. 114.

- Foxell 1996, p. 69.

- Jackson 2006, pp. 130–131.

- Foxell 2010, p. 115.

- Foxell 1996, pp. 69–70.

- Foxell 1996, p. 70.

- Horne 2003, p. 75.

- Foxell 2010, p. 117.

- Simpson 2004, p. 40.

- Mitchell & Smith 2005, §51.

- Foxell 2010, p. 90.

- Oppitz 2000, p. 38.

- Oppitz 2000, p. 39.

- Foxell 1996, pp. 72–73.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Foxell 1996, p. 73.

- Foxell 2010, p. 118.

- Hornby 1999, p. 28.

- Foxell 1996, p. 74.

- Hornby 1999, pp. 28–29.

- Foxell 1996, p. 75.

- Foxell 2010, p. 146.

- Foxell 1996, p. 78.

- Foxell 1996, p. 77.

- Foxell 2010, p. 144.

- "Crossrail Maps". London: Crossrail. Archived from the original on 23 August 2009. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- Bruce & Croome 1996, p. 80.

- Foxell 2010, p. 140.

- Foxell 2010, pp. 140–141.

- Foxell 2010, p. 142.

- "Last Chesham Shuttle Before the Through Trains". Chiltern Voice. Chesham. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

Bibliography

- Bruce, J. Graeme; Croome, Desmond F. (1996). The Twopenny Tube. Harrow Weald: Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-186-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cockman, F. G. (2006). David, Thorpe (ed.). "The Railways of Buckinghamshire from the 1830: An account of those that were not built as well as those which were". Buckinghamshire Papers. Aylesbury: Buckinghamshire Archaeological Society (8). ISBN 0-949003-22-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Demuth, Tim (2003). The Spread of London's Underground. Harrow Weald: Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-266-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Foxell, Clive (1996). Chesham Shuttle (2 ed.). Chesham: Clive Foxell. ISBN 0-9529184-0-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Foxell, Clive (2010). The Metropolitan Line: London's first underground railway. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-5396-5. OCLC 501397186.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Halliday, Stephen (2001). Underground to Everywhere. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-2585-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hornby, Frank (1999). London Commuter Lines: Main lines north of the Thames. A history of the capital's suburban railways in the BR era, 1948–95. 1. Kettering: Silver Link. ISBN 1-85794-115-2. OCLC 43541211.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Horne, Mike (2003). The Metropolitan Line: An illustrated history. Harrow Weald: Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-275-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jackson, Alan (2006). London's Metro-Land. Harrow: Capital History. ISBN 1-85414-300-X. OCLC 144595813.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, Ken (1974). The Wotton Tramway (Brill Branch). Locomotion Papers. Blandford: The Oakwood Press. ISBN 0-85361-149-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, Charles E. (1935). "The Duke of Buckingham's Railways: with special reference to the Brill line". Railway Magazine. 77 (460): 235–241.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Melton, Ian (1984). R. J., Greenaway (ed.). "From Quainton to Brill: A history of the Wotton Tramway". Underground. Hemel Hempstead: The London Underground Railway Society (13). ISSN 0306-8609.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mitchell, Vic; Smith, Keith (2005). Rickmansworth to Aylesbury. Midhurst: Middleton Press. ISBN 1-904474-61-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mitchell, Vic; Smith, Keith (2006). Aylesbury to Rugby. Midhurst: Middleton Press. ISBN 1-904474-91-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oppitz, Leslie (2000). Lost Railways of the Chilterns. Newbury: Countryside Books. ISBN 1-85306-643-5. OCLC 45682620.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Simpson, Bill (1985). The Brill Tramway. Poole: Oxford Publishing. ISBN 0-86093-218-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Simpson, Bill (2003). A History of the Metropolitan Railway. 1. Witney: Lamplight Publications. ISBN 1-899246-07-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Simpson, Bill (2004). A History of the Metropolitan Railway. 2. Witney: Lamplight Publications. ISBN 1-899246-08-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Simpson, Bill (2005). A History of the Metropolitan Railway. 3. Witney: Lamplight Publications. ISBN 1-899246-13-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilson, Jeremy; Spick, Jerome (1994). Eurotunnel: The Illustrated Journey. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-255539-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wolmar, Christian (2004). The Subterranean Railway. London: Atlantic. ISBN 1-84354-023-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Mitchell, Vic; Smith, Keith (2006). Baker Street to Uxbridge & Stanmore. Midhurst: Middleton Press. ISBN 1-904474-90-X. OCLC 171110119.

- Mitchell, Vic; Smith, Keith (2005). Marylebone to Rickmansworth. Midhurst: Middleton Press. ISBN 1-904474-49-7. OCLC 64118587.

- Reed, Albin J. (1997). The Met & G C Joint Line: An Observer's Notes 1948–68 (2001 ed.). Stoke Mandeville: Albin J. Reed. ISBN 0-9536252-4-9.