Orange Free State

The Orange Free State (Dutch: Oranje Vrijstaat,[lower-alpha 1] Afrikaans: Oranje-Vrystaat,[lower-alpha 2] abbreviated as OVS[2]) was an independent Boer sovereign republic in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeated and surrendered to the British Empire at the end of the Second Boer War in 1902. It is the historical precursor to the present-day Free State province.[3]

Orange Free State | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1854–1902 | |||||||||

Anthem: Vrystaatse Volkslied | |||||||||

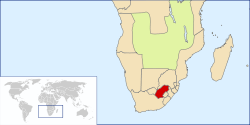

Location of the Orange Free State c. 1890 | |||||||||

| Capital | Bloemfontein | ||||||||

| Common languages | Dutch (official), Afrikaans, English, Sesotho, Setswana | ||||||||

| Religion | Dutch Reformed Dutch Reformed dissenters | ||||||||

| Government | Republic | ||||||||

| State President | |||||||||

• 1854–1855 | Josias P Hoffman | ||||||||

• 1855–1859 | J N Boshoff | ||||||||

• 1860–1863 | Marthinus Wessel Pretorius1 | ||||||||

• 1864–1888 | Jan H Brand | ||||||||

• 1889–1895 | Francis William Reitz | ||||||||

• 1896–1902 | Marthinus Theunis Steyn | ||||||||

• 30 to 31 May 1902 | Christiaan de Wet | ||||||||

| Legislature | Volksraad | ||||||||

| Historical era | 19th century | ||||||||

• Republic founded | 17 February 1854 | ||||||||

| 16 December 1838 | |||||||||

• Start of 2nd Boer War | 11 October 1899 | ||||||||

| 31 May 1902 | |||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1875[1] | 181,299 km2 (70,000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1875[1] | 100,000 | ||||||||

| Currency | Orange Free State pound | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

1 Also State President of the Republic of Transvaal | |||||||||

Extending between the Orange and Vaal rivers, its borders were determined by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in 1848 when the region was proclaimed as the Orange River Sovereignty, with a British Resident based in Bloemfontein.[4] Bloemfontein and the southern parts of the Sovereignty had previously been settled by Griqua and by Trekboere from the Cape Colony.

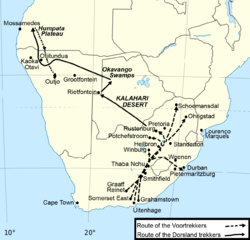

The Voortrekker Republic of Natalia, founded in 1837, administered the northern part of the territory through a landdrost based at Winburg. This northern area was later in federation with the Republic of Potchefstroom which eventually formed part of the South African Republic (Transvaal).[4]

Following the granting of sovereignty to the Transvaal Republic, the British recognised the independence of the Orange River Sovereignty and the country officially became independent as the Orange Free State on 23 February 1854, with the signing of the Orange River Convention. The new republic incorporated the Orange River Sovereignty and continued the traditions of the Winburg-Potchefstroom Republic.[4]

The Orange Free State developed into a politically and economically successful republic and for the most part enjoyed good relationships with its neighbours. It was annexed as the Orange River Colony in 1900. It ceased to exist as an independent Boer republic on 31 May 1902 with the signing of the Treaty of Vereeniging at the conclusion of the Second Boer War. Following a period of direct rule by the British, it attained self-government in 1907 and joined the Union of South Africa in 1910 as the Orange Free State Province, along with the Cape Province, Natal, and the Transvaal.[4] In 1961, the Union of South Africa became the Republic of South Africa.[3]

The republic's name derives partly from the Orange River, which in turn was named in honour of the Dutch ruling family, the House of Orange, by the Dutch explorer Robert Jacob Gordon.[5] The official language in the Orange Free State was Dutch.[4]

History

Before the Voortrekkers

Europeans first visited the country north of the Orange River towards the close of the 18th century. One of the most notable visitors was the Dutch explorer Robert Jacob Gordon, who mapped the region and gave the Orange River its name.[6] At that time, the population was sparse. The majority of the inhabitants appear to have been members of the Sotho people (colonial form Basuto), but in the valleys of the Orange and Vaal were Korana and other Khoikhoi, and in the Drakensberg and on the western border lived numbers of Bushmen. Early in the 19th century Griqua established themselves north of the Orange.

Boer immigration

In 1824 farmers of Dutch, French Huguenot and German descent known as Voortrekkers (later named Boers by the English) emerged from the Cape Colony, seeking pasture for their flocks and to escape British governmental oversight, settling in the country. Up to this time the few Europeans who had crossed the Orange had come mainly as hunters or as missionaries. These early migrants were followed in 1836 by the first parties of the Great Trek. These emigrants left the Cape Colony for various reasons, but all shared the desire for independence from British authority. The leader of the first large party, Hendrik Potgieter, concluded an agreement with Makwana, the chief of the Bataung tribe of Batswana, ceding to the farmers the country between the Vet and Vaal rivers.[4] When Boer families first reached the area they discovered that the country had been devastated, in the northern parts by the chief Mzilikazi and his Matabele in what was known as the Mfecane, and also by the Difaqane, in which three tribes roamed across the land attacking settled groups, absorbing them and their resources until they collapsed because of their sheer size. Consequently, large areas were depopulated.[4] The Boers soon came into collision with Mzilikazi's raiding parties, which attacked Boer hunters who crossed the Vaal River. Reprisals followed, and in November 1837 the Boers decisively defeated Mzilikazi, who thereupon fled northward[4] and eventually established himself on the site of the future Bulawayo in Zimbabwe.

In the meantime another party of Cape Dutch emigrants had settled at Thaba Nchu, where the Wesleyans had a mission station for the Barolong. These Barolong had trekked from their original home under their chief, Moroka II, first south-westwards to the Langberg, and then eastwards to Thaba Nchu. The emigrants were treated with great kindness by Moroka, and with the Barolong the Boers maintained uniformly friendly relations after they defeated Mzilikazi. In December 1836 the emigrants beyond the Orange drew up in general assembly an elementary republican form of government. After the defeat of Mzilikazi the town of Winburg (so named by the Boers in commemoration of their victory) was founded, a Volksraad elected, and Piet Retief, one of the ablest of the Voortrekkers, chosen “governor and commandant-general”. The emigrants already numbered some 500 men, besides women and children and many servants. Dissensions speedily arose among the emigrants, whose numbers were constantly added to, and Retief, Potgieter and other leaders crossed the Drakensberg and entered Natal. Those that remained were divided into several parties.[7]

British rule

Meanwhile, a new power had arisen along the upper Orange and in the valley of the Caledon. Moshoeshoe, a minor Basotho chief, had welded together a number of scattered and broken clans which had sought refuge in that mountainous region after fleeing from Mzilikazi, and had formed the Basotho nation which acknowledged him as king. In 1833 he had welcomed as workers among his people a band of French Protestant missionaries, and as the Boer immigrants began to settle in his neighborhood he decided to seek support from the British at the Cape. At that time the British government was not prepared to exercise control over the immigrants. Acting upon the advice of Dr John Philip, the superintendent of the London Missionary Society’s stations in South Africa, a treaty was concluded in 1843 with Moshoeshoe, placing him under British protection. A similar treaty was made with the Griqua chief Adam Kok III. By these treaties, which recognised native sovereignty over large areas on which Boer farmers were settled, the British sought to keep a check on the Boers and to protect both the natives and Cape Colony. The effect was to precipitate collisions between all three parties.[7]

The year in which the treaty with Moshoeshoe was made, several large parties of Boers recrossed the Drakensberg into the country north of the Orange, refusing to remain in Natal when the British annexed the newly formed Boer republic of Natalia to form the Colony of Natal. During their stay in Natal the Boers inflicted a severe defeat on the Zulus under Dingane in the Battle of Blood River in December 1838, which, following on the flight of Mzilikazi, greatly strengthened the position of Moshoeshoe, whose power became a menace to that of the Boer farmers. Trouble first arose, however, between the Boers and the Griqua in the Philippolis district. Some of the Boer farmers in this district, unlike their fellows dwelling farther north, were willing to accept British rule. This fact induced Mr Justice Menzies, one of the judges of Cape Colony then on circuit at Colesberg, to cross the Orange and proclaim the country British territory in October 1842. The proclamation was disallowed by the governor, Sir George Napier, who, nevertheless, maintained that the Boer farmers remained British subjects. After this episode the British negotiated their treaties with Adam Kok III and Moshoeshoe.[7]

The treaties gave great offence to the Boers, who refused to acknowledge the sovereignty of the native chiefs. The majority of the Boer farmers in Kok's territory sent a deputation to the British commissioner in Natal, Henry Cloete, asking for equal treatment with the Griquas, and expressing the desire to come under British protection under such terms. Shortly afterwards hostilities between the farmers and the Griqua broke out. British troops moved up to support the Griquas, and after a skirmish at Zwartkopjes (2 May 1845) a new arrangement was made between Kok and Peregrine Maitland, then governor of Cape Colony, virtually placing the administration of his territory in the hands of a British resident, a post filled in 1846 by Captain Henry Douglas Warden. The place purchased by Captain (afterwards Major) Warden as the seat of his court was known as Bloemfontein, and it subsequently became the capital of the whole country.[7] Bloemfontein lay to the south of the region settled by Voortrekkers.

Boer governance

The Volksraad at Winburg during this period continued to claim jurisdiction over the Boers living between the Orange and the Vaal and was in federation with the Volksraad at Potchefstroom, which made a similar claim upon the Great Boers living north of the Vaal. In 1846 Major Warden occupied Winburg for a short time, and the relations between the Boers and the British were in a continual state of tension. Many of the farmers deserted Winburg for the Transvaal. Sir Harry Smith became governor of the Cape at the end of 1847. He recognised the failure of the attempt to govern on the lines of the treaties with the Griquas and Basotho, and on 3 February 1848 he issued a proclamation declaring British sovereignty over the country between the Orange and the Vaal eastward to the Drakensberg. Sir Harry Smith's popularity among the Boers gained for his policy considerable support, but the republican party, at whose head was Andries Pretorius, did not submit without a struggle. They were, however, defeated by Sir Harry Smith in the Battle of Boomplaats on 29 August 1848. Thereupon Pretorius, with those most bitterly opposed to British rule, retreated across the Vaal.[7]

Orange River Sovereignty

In March 1849 Major Warden was succeeded at Bloemfontein as civil commissioner by Mr C. U. Stuart, but he remained the British resident until July 1852. A nominated legislative council was created, a high court established and other steps taken for the orderly government of the country, which was officially styled the Orange River Sovereignty. In October 1849 Moshoeshoe was induced to sign a new arrangement considerably curtailing the boundaries of the Basotho reserve. The frontier towards the Sovereignty was thereafter known as the Warden line. A little later the reserves of other chieftains were precisely defined.[7]

The British Resident had, however, no force sufficient to maintain his authority, and Moshoeshoe and all the neighboring clans became involved in hostilities with one another and with the Europeans. In 1851 Moshoeshoe joined the republican party in the Sovereignty in an invitation to Pretorius to recross the Vaal. The intervention of Pretorius resulted in the Sand River Convention of 1852, which acknowledged the independence of the Transvaal but left the status of the Sovereignty untouched. The British government (under the first Russell administration), which had reluctantly agreed to the annexation of the country, had, however, already repented its decision and had resolved to abandon the Sovereignty. Lord Henry Grey, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, in a dispatch to Sir Harry Smith dated 21 October 1851, declared, "The ultimate abandonment of the Orange Sovereignty should be a settled point in our policy."[7]

A meeting of representatives of all European inhabitants of the Sovereignty, elected on manhood suffrage, held at Bloemfontein in June 1852, nevertheless declared in favour of the retention of British rule. At the close of that year a settlement was at length concluded with Moshoeshoe, which left, perhaps, that chief in a stronger position than he had hitherto been. There had been ministerial changes in England and the Aberdeen ministry, then in power, adhered to the determination to withdraw from the Sovereignty. Sir George Russell Clerk was sent out in 1853 as special commissioner "for the settling and adjusting of the affairs" of the Sovereignty, and in August of that year he summoned a meeting of delegates to determine upon a form of self-government.[7]

At that time there were some 15,000 Europeans in the country, many of them recent immigrants from Cape Colony. There were among them numbers of farmers and tradesmen of British descent. The majority of the whites still wished for the continuance of British rule provided that it was effective and the country guarded against its enemies. The representations of their delegates, who drew up a proposed constitution retaining British control, were unavailing. Sir George Clerk announced that, as the elected delegates were unwilling to take steps to form an independent government, he would enter into negotiations with other persons. " And then," wrote George McCall Theal, "was seen forced the strange spectacle of an English commissioner addressing men who wished to be free of British control as the friendly and well-disposed inhabitants, while for those who desired to remain British subjects and who claimed that protection to which they believed themselves entitled he had no sympathising word."[8] While the elected delegates sent two members to England to try and induce the government to alter their decision, Sir George Clerk speedily came to terms with a committee formed by the republican party and presided over by Mr J. H. Hoffman. Even before this committee met a royal proclamation had been signed (30 January 1854) "abandoning and renouncing all dominion" in the Sovereignty.[7]

The Orange River Convention, recognising the independence of the country, was signed at Bloemfontein on 23 February by Sir George Clerk and the republican committee, and in March the Boer government assumed office and the republican flag was hoisted. Five days later the representatives of the elected delegates had an interview in London with the colonial secretary, the Duke of Newcastle, who informed them that it was now too late to discuss the question of the retention of British rule. The colonial secretary added that it was impossible for England to supply troops to constantly advancing outposts, "especially as Cape Town and the port of Table Bay were all she really required in South Africa." In withdrawing from the Sovereignty the British government declared that it had "no alliance with any native chief or tribes to the northward of the Orange River with the exception of the Griqua chief Captain Adam Kok [III]". Kok was not formidable in a military sense, nor could he prevent individual Griquas from alienating their lands. Eventually, in 1861, he sold his sovereign rights to the Free State for £4000 and moved with his followers to the district later known as Griqualand East.[7]

On the abandonment of British rule, representatives of the people were elected and met at Bloemfontein on 28 March 1854, and between then and 18 April were engaged in framing a constitution. The country was declared a republic and named the Orange Free State. All persons of European blood possessing a six months' residential qualification were to be granted full burgher rights. The sole legislative authority was vested in a single popularly elected chamber of the Volksraad. Executive authority was entrusted to a president elected by the burghers from a list submitted by the Volksraad. The president was to be assisted by an executive council, was to hold office for five years and was eligible for re-election. The constitution was subsequently modified but remained of a liberal character. A residence of five years in the country was required before aliens could become naturalised. The first president was Josias Philip Hoffman, but he was accused of being too complaisant towards Moshoeshoe and resigned, being succeeded in 1855 by Jacobus Nicolaas Boshoff, one of the voortrekkers, who had previously taken an active part in the affairs of the Natalia Republic.[7]

Conflict with the South African Republic

Distracted among themselves, with the formidable Basotho power on their southern and eastern flank, the troubles of the infant state were speedily added to by the action of the Transvaal Boers of the South African Republic. Marthinus Pretorius, who had succeeded to his father's position as commandant general of Potchefstroom, wished to bring about a confederation between the two Boer states. Peaceful overtures from Pretorius were declined, and some of his partisans in the Free State were accused of treason in February 1857. Thereupon Pretorius, aided by Paul Kruger, conducted a raid into the Free State territory. On learning of the invasion President Jacobus Nicolaas Boshoff proclaimed martial law throughout the country. The majority of the burghers rallied to his support, and on 25 May the two opposing forces faced one another on the banks of the Rhenoster. President Boshoff not only got together some 800 men within the Free State, but he received offers of support from Commandant Stephanus Schoeman, the Transvaal leader in the Zoutpansberg district and from Commandant Joubert of Lydenburg. Pretorius and Kruger, realising that they would have to sustain attack from both north and south, abandoned their enterprise. Their force, too, only amounted to some three hundred. Kruger came to Boshoff's camp with a flag of truce, the "army" of Pretorius returned north and on 2 June a treaty of peace was signed, each state acknowledging the absolute independence of the other.[7]

The conduct of Pretorius was stigmatised as "blameworthy." Several of the malcontents in the Free State who had joined Pretorius permanently settled in the Transvaal, and other Free Staters who had been guilty of high treason were arrested and punished. This experience did not, however, heal the party strife within the Free State. In consequence of the dissensions among the burghers President Boshoff tendered his resignation in February 1858, but was for a time induced to remain in office. The difficulties of the state were at that time so great that the Volksraad in December 1858 passed a resolution in favor of confederation with the Cape Colony. This proposition received the strong support of Sir George Grey, then governor of Cape Colony, but his view did not commend itself to the British government, and was not adopted.[7]

In the same year, the disputes between the Basotho and the Boers culminated in open war. Both parties laid claims to land beyond the Warden line, and each party had taken possession of what it could, the Basotho being also expert cattle-lifters. In the war the advantage rested with the Basotho; thereupon the Free State appealed to Sir George Grey, who induced Moshoeshoe to come to terms. On 15 October 1858, a treaty was signed defining the new boundary. The peace was nominal only, while the burghers were also involved in disputes with other tribes. Mr. Boshoff again tendered his resignation in February 1859 and retired to Natal. Many of the burghers would have at this time welcomed union with the Transvaal, but learning from Sir George Grey that such a union would nullify the conventions of 1852 and 1854 and necessitate the reconsideration of Great Britain's policy towards the native tribes north of the Orange and Vaal rivers, the project was dropped. Commandant Marthinus Wessel Pretorius was, however, elected president in place of Mr Boshoff. Though unable to effect a durable peace with the Basotho, or to realise his ambition for the creation of one powerful Boer republic, Pretorius saw the Free State begin to grow in strength. The fertile district of Bethulie as well as Adam Kok's territory was acquired, and there was a considerable increase in the Boer population. The burghers generally, however, had little confidence in their elected rulers and little desire for taxes to be levied. Wearied like Mr Boshoff, and more interested in affairs in the Transvaal than in those of the Free State, Pretorius resigned the presidency in 1863.[7]

After an interval of seven months, Johannes Brand, an advocate at the Cape bar, was elected president. He assumed office in February 1864. His election proved a turning-point in the history of the country, which, under his guidance, became peaceful and prosperous. But before peace could be established an end had to be made of the difficulties with the Basothos. Moshoeshoe continued to menace the Free State border. Attempts at accommodation made by the governor of Cape Colony, Sir Philip Wodehouse, failed, and war between the Free State and Moshoeshoe was renewed in 1865. The Boers gained considerable successes, and this induced Moshoeshoe to sue for peace. The terms exacted were, however, too harsh for a nation yet unbroken to accept permanently. A treaty was signed at Thaba Bosiu in April 1866, but war again broke out in 1867, and the Free State attracted to its side a large number of adventurers from all parts of South Africa. The burghers thus reinforced gained at length a decisive victory over their great antagonist, every stronghold in Basutoland save Thaba Bosiu being stormed. Moshoeshoe now turned to Sir Philip Wodehouse for preservation. His call was heeded, and in 1868 he and his country were taken under British protection. Thus the thirty years' strife between the Basothos and the Boers came to an end. The intervention of the governor of Cape Colony led to the conclusion of the treaty of Aliwal North (12 February 1869), which defined the borders between the Orange Free State and Basutoland. The country lying to the north of the Orange River and west of the Caledon River, formerly a part of Basutoland, was ceded to the Free State, and became known as the Conquered Territory.[7]

A year after the addition of the Conquered Territory to the state another boundary dispute was settled by the arbitration of Robert William Keate, lieutenant-governor of Natal. By the Sand River Convention, independence had been granted to the Boers living "north of the Vaal", and the dispute turned on the question as to what stream constituted the true upper course of that river. Mr Keate decided on 19 February 1870 against the Free State view and fixed the Klip River as the dividing line, the Transvaal thus securing the Wakkerstroom and adjacent districts.[7]

Diamonds discovered

The Basutoland difficulties were no sooner arranged than the Free Staters found themselves confronted with a serious difficulty on their western border. In the years 1870–1871 a large number of foreign diggers had settled on the diamond fields near the junction of the Vaal and Orange rivers, which were situated in part on land claimed by the Griqua chief Nicholas Waterboer and by the Free State.[7]

The Free State established a temporary government over the diamond fields, but the administration of this body was satisfactory neither to the Free State nor to the diggers. At this juncture Waterboer offered to place the territory under the administration of Queen Victoria. The offer was accepted, and on 27 October 1871 the district, together with some adjacent territory to which the Transvaal had laid claim, was proclaimed, under the name of Griqualand West, British territory. Waterboer's claims were based on the treaty concluded by his father with the British in 1834, and on various arrangements with the Kok chiefs; the Free State based its claim on its purchase of Adam Kok's sovereign rights and on long occupation. The difference between proprietorship and sovereignty was confused or ignored. That Waterboer exercised no authority in the disputed district was admitted. When the British annexation took place a party in the Volksraad wished to go to war with Britain, but the counsels of President Johannes Brand prevailed. The Free State, however, did not abandon its claims. The matter involved no little irritation between the parties concerned until July 1876. It was then disposed of by Henry Herbert, 4th Earl of Carnarvon, at that time Secretary of State for the Colonies, who granted to the Free State a £90,000 payment "in full satisfaction of all claims which it considers it may possess to Griqualand West." Lord Carnarvon declined to entertain the proposal made by Mr Brand that the territory should be given up by Great Britain.[7] In the opinion of historian George McCall Theal, the annexation of Griqualand West was probably in the best interests of the Free State. "There was," he stated, "no alternative from British sovereignty other than an independent diamond field republic."[8]

At this time, largely owing to the struggle with the Basothos, the Free State Boers, like their Transvaal neighbors, had drifted into financial straits. A paper currency had been instituted, and the notes, known as "bluebacks", soon dropped to less than half their nominal value. Commerce was largely carried on by barter, and many cases of bankruptcy occurred in the state. The influx of British and other immigrants to the diamond fields, in the early 1870s, restored public credit and individual prosperity to the Boers of the Free State. The diamond fields offered a ready market for stock and other agricultural produce. Money flowed into the pockets of the farmers. Public credit was restored. "Bluebacks" recovered par value, and were called in and redeemed by the government. Valuable diamond mines were also discovered within the Free State, of which the one at Jagersfontein was the richest. Capital from Kimberley and London was soon provided with which to work them.[7]

Peaceful relations with neighbours

The relations between the British and the Free State, after the question of the boundary was settled, remained perfectly amicable down to the outbreak of the Second Boer War in 1899. From 1870 onward the history of the state was one of quiet, steady progress. At the time of the first annexation of the Transvaal the Free State declined Lord Carnarvon's invitation to federate with the other South African communities. In 1880, when a rising of the Boers in the Transvaal was threatening, President Brand showed every desire to avert the conflict. He suggested that Sir Henry de Villiers, Chief Justice of Cape Colony, should be sent into the Transvaal to endeavour to gauge the true state of affairs in that country. This suggestion was not acted upon, but when war broke out in the Transvaal, Brand declined to take any part in the struggle. In spite of the neutral attitude taken by their government a number of the Free State Boers, living in the northern part of the country, went to the Transvaal and joined their brethren then in arms against the British. This fact was not allowed to influence the friendly relations between the Free State and Great Britain. In 1888 Sir Johannes Brand died.[7]

During the period of Brand's presidency a great change, both political and economic, had come over South Africa. The renewal of the policy of British expansion had been answered by the formation of the Afrikaner Bond, which represented the aspirations of the Afrikaner people, and had active branches in the Free State. This alteration in the political outlook was accompanied, and in part occasioned, by economic changes of great significance. The development of the diamond mines and of the gold and coal industries — of which Brand saw the beginning — had far-reaching consequences, bringing the Boer republics into contact with the new industrial era. The Free Staters, under Brand's rule, had shown considerable ability to adapt their policy to meet the altered situation. In 1889 an agreement made between the Free State and the Cape Colony government, whereby the latter was empowered to extend, at its own cost, its railway system to Bloemfontein. The Free State retained the right to purchase this extension at cost, a right it exercised after the Jameson Raid.[7]

Having accepted the assistance of the Cape government in constructing its railway, the state also in 1889 entered into a Customs Union Convention with them. The convention was the outcome of a conference held at Cape Town in 1888, at which delegates from Natal, the Free State and the Cape Colony attended. Natal at this time had not seen its way to entering the Customs Union, but did so at a later date.[7]

Renewal of hostilities

In January 1889 Francis William Reitz was elected president of the Free State. Reitz had no sooner got into office than a meeting was arranged with Paul Kruger, president of the South African Republic, at which various terms were discussed and decided upon regarding an agreement dealing with the railways, terms of a treaty of amity and commerce, and what was called a political treaty. The political treaty referred in general terms to a federal union between the South African Republic and the Orange Free State, and bound each of them to help the other, whenever the independence of either should be assailed or threatened from without, unless the state so called upon for assistance should be able to show the injustice of the cause of quarrel in which the other state had engaged. While thus committed to an alliance with its northern neighbour no change was made in internal administration. The Free State, in fact, from its geographical position reaped the benefits without incurring the anxieties consequent on the settlement of a large Uitlander population on the Witwatersrand. The state, however, became increasingly identified with the reactionary party in the South African Republic.

In 1895 the Volksraad passed a resolution, in which they declared their readiness to entertain a proposition from the South African Republic in favour of some form of federal union. In the same year Reitz retired from the presidency of the Orange Free State. The 1896 presidential election to succeed him was won by M. T. Steyn, a judge of the High Court, who took office in February 1896. In 1896 President Steyn visited Pretoria, where he received an ovation as the probable future president of the two Republics. A further offensive and defensive alliance between the two Republics was then entered into, under which the Orange Free State took up arms on the outbreak of hostilities between the British and the South African Republic in October 1899.[7]

In 1897 President Kruger, bent on still further cementing the union with the Orange Free State, had visited Bloemfontein. It was on this occasion that Kruger, referring to the London Convention, spoke of Queen Victoria as a kwaaje Vrouw (angry woman), an expression which caused a good deal of offence in England at the time, but which, in the phraseology of the Boers, was not meant by President Kruger as insulting.[7]

In December 1897 the Free State revised its constitution in reference to the franchise law, and the period of residence necessary to obtain naturalization was reduced from five to three years. The oath of allegiance to the state was alone required, and no renunciation of nationality was insisted upon. In 1898 the Free State also acquiesced in the new convention arranged with regard to the Customs Union between the Cape Colony, Natal, Basutoland and the Bechuanaland Protectorate. But events were moving rapidly in the Transvaal, and matters had proceeded too far for the Free State to turn back. In May 1899 President Steyn suggested the conference at Bloemfontein between President Kruger and Sir Alfred Milner, but this act was too late. The Free Staters were practically bound to the South African Republic, under the offensive and defensive alliance, in case hostilities arose with Great Britain.[7]

The Free State began to expel British subjects in 1899, and the first act of the Second Boer War was committed by Free State Boers, who, on 11 October 1899, seized a train upon the border belonging to Natal. For President Steyn and the Free State of 1899, neutrality was impossible. A resolution was passed by the volksraad on 27 September declaring that the state would observe its obligations to the Transvaal whatever might happen.[7]

After the surrender of Piet Cronjé in the Battle of Paardeberg on 27 February 1900, Bloemfontein was occupied by the British troops under Lord Roberts from 13 March onward, and on 28 May a proclamation was issued annexing the Free State to the British dominions under the title of Orange River Colony. For nearly two years longer the burghers kept the field under Christiaan de Wet and other leaders, but by the articles of peace signed on 31 May 1902 British sovereignty was acknowledged.[7]

Politics

Divisions

The country was divided into the following districts:[9]

- Bloemfontein district: Bloemfontein, Reddersburg, Brandfort, Bethany, Edenburg

- Caledon River district: Smithfield

- Winburg district: Winburg, Ventersburg

- Harrismith district: Harrismith, Frankfort

- Kroonstad district: Kroonstad, Heilbron

- Boshof district: Boshof

- Jacobsdal district: Jacobsdal

- Philippolis district: Philippolis

- Bethulie district: Bethulie

- Bethlehem district: Bethlehem

- Rouxville district: Rouxville

- Lady Brand district: Lady Brand, Ficksburg

- Pniel district: Pniel

Demographics

An estimate in 1875: White: 75,000; Native and Colored: 25,000.[1] The first census, carried out in 1880, found that 'Europeans' made up 45.7% of the population.[10] Bloemfontein, the capital, had 2,567 inhabitants.[11] The 1890 census, which was reportedly not very accurate, found a population of 207,503.[12]

In 1904 the colonial census was taken. The population was 387.315, of whom 225.101 (58.11%) were blacks, 142.679 (36.84%) were whites, 19.282 (4.98%) were coloreds and 253 (0.07%) were Indians. The largest cities were Bloemfontein (33.883) (whites - 15.501 or 45.74%), Harrismith (8.300) (whites - 4.817 or 58.03%), Kroonstad (7.191) (whites - 3.708 or 51.56%).

In 1911 population was 528.174, of whom 325.824 (61.68%) were blacks, 175.189 (33.16%) were whites, 26.554 (5.02%) were coloreds and 607 (0.11%) were Indians. The capital, Bloemfontein, had a population of 26.925.

See also

Notes

- Dutch pronunciation: [oːˈrɑɲə ˈvrɛistaːt]

- Afrikaans pronunciation: [ʊəˈraɲə ˈfrɛɪstɑːt]

References

- Sketch of the Orange Free State of South Africa. Bloemfontein: Orange Free State. Commission at the International Exhibition, Philadelphia, 1876. 1876. p. 10. Archived from the original on 29 May 2016.

- "What does OVS stand for?". Acronym Finder. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- "Free State". Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 November 2009. Archived from the original on 14 March 2017.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- "Introduction to the Orange River basin". Department of Water and Sanitation, South Africa. Archived from the original on 14 March 2017. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- "About". Robert Jacob Gordon. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

-

- G. McCall Theal, History of South Africa since 1795 [up to 1872], vols. ii., iii. and iv. (1908 ed.), quoted in Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Sketch of the Orange Free State of South Africa. Bloemfontein: Orange Free State. Commission at the International Exhibition, Philadelphia, 1876. 1876. pp. 5–6. Archived from the original on 29 May 2016.

- Christopher, Anthony J. (June 2010). "A South African Domesday Book: the first Union census of 1911". South African Geographical Journal. 92 (1): 22–34. doi:10.1080/03736245.2010.483882.

- "The first census in the Orange Free State is held". South Africa History. Archived from the original on 30 January 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- Orange Free State Republic, South Africa. Rand, McNally & Co., Printers. 1893. p. 5. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

![]()

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |