Dorsland Trek

Dorsland Trek (Thirstland Trek) is the collective name of a series of explorations undertaken by Boer settlers from South Africa towards the end of the 19th century and in the first years of the 20th century, in search of political independence and better living conditions. The participants, Trekboere ("migrating farmers"; the singular is trekboer) from the Orange Free State and Transvaal, are called Dorslandtrekkers or Angola-Boere.[1]

Political background and previous treks

After escaping the rule of the Dutch East India Company in the late 18th century, semi-nomadic settlers at the Cape Colony came into conflict both with the indigenous Xhosa tribes in the east and the British Empire, which had acquired the Cape as a result of the Napoleonic Wars. In 1836, the Boers set off on what became known as the Great Trek, establishing the Orange Free State and Transvaal as independent Boer republics.[2]

There are two theories why the settlers would take off yet again to explore territory further north. One is that in the 1870s, Britain again began the process of annexing the Boer states;[3] the second theory claims that "[t]hey appeared compelled by a desire to trek", with no particular difficulty facing them at their current place.[2]

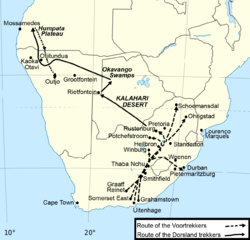

Routes of the trek

The first group of the Dorsland Trek set out on 27 May 1874 under the leadership of Gert Alberts.[4] A number of different groups of farmers, taking different routes, followed the first group. They set off from the areas around Rustenburg,[2] Groot Marico,[5] and Pretoria.[3] The primary destination was the Humpata highlands of south-western Angola. On their journey, the settlers had to traverse Bechuanaland and the vast, arid areas of the Kalahari desert, in what is today the countries of Namibia and Botswana.[6] It was the harsh and dry conditions that they experienced in the Kalahari that gave the trek the name Dorsland Trek which means "Thirstland Trek" in the Afrikaans language.[5] According to one witness, over 3000 trekkers died during the journey.[6] In 1881, sixty families totaling 300 people arrived in Humpata, and were given 200 hectares (490 acres) per family to farm on.[1]

The settlers entered Angola by crossing the Cunene River at Swartbooisdrift. The Portuguese colonial authorities encouraged the Boers to settle on the Huíla Plateau at Humpata where the majority of them remained, while a number of families went further north, settling at different places on the Central Highlands. The various settlements formed one closed community that resisted integration. Also, the settlers' resistance to innovation brought many of them to impoverishment. As a result, in the late 1920s, some began migrating southwards into South-West Africa,[3] while some returned to South Africa.[2][7] They left Angola on ox wagons, taking only what they could load on the wagons.[8] The descendants of the Dorsland trekkers — not fully integrated into Portuguese Angolan society — left Angola in 1975, when the country became independent amid a civil war.

A number of farmers settled in the Otavi – Tsumeb – Grootfontein triangle[3] and in the area around Gobabis. Some took a different route and crossed Kaokoland.[5] On their way southwards they discovered water at Tsauchab and named it Ses Riem, (Six Reins, after the long reins which were part of the ox wagon harness), which reflected the depth of the canyon.[3]

Great Trek from Angola

Not long after the Boers first settled in Angola, problems arose. The Afrikaners taught the local Portuguese settlers cattle breeding and ox-cart driving, as well as superior marksmanship. The relationship between the Portuguese settlers and the Boers was quite cordial, and many Portuguese learned Afrikaans as well. The Portuguese authorities, however, did not approve of the Boers in Angola and never granted them citizenship, did not allow them to have legal ownership of their farms, and did not allow them to open Afrikaans language schools. As early as the mid 1890s, the tensions between the colonial authorities and the Boer settlers was apparent, and was written about at the time by the Swedish explorer Peter Möller.

In 1928 many Boers decided to leave Angola and head south to South-West Africa (then under South African jurisdiction), where settlement was easier and not impeded on by the Portuguese authorities. The repatriation was conducted by the South African government under J. B. M. Hertzog. From August 1928 to February 1929, 1,922 Boers were repatriated to South Africa. 420 trek certificates were issued to families, though only 373 families left Angola at the time. The final Boer families to return to South Africa under this repatriation left Angola in 1931. [9]

After the Great Trek from Angola, many Boers stayed in Angola, and the remaining Afrikaner community erected an obelisk monument in Humpata in July 1957 in honor of the Dorsland Trekkers. By 1958, 58 Boer families remained in Angola, totaling 500 individuals.[10] These Boers remained in Angola until 1975, during the Angolan Civil War, when they fled with many thousands of Portuguese refugees into South West Africa (now called Namibia). Today, an unknown number of Boers live in Angola, as with the end of the civil war, many Portuguese and others have returned to the country.

Historical impact

The Boers were not well received everywhere. As early as 1874, Herero chiefs Maharero, Kambazembi, and Christian Wilhelm Zeraua requested the Cape authorities to intervene with their settlement in Damaraland. As a result, a position of Special Commissioner for Damaraland was created.[11] In the area around Gobabis, Kaiǀkhauan Kaptein Andreas Lambert on behalf of all leaders of Damaraland threatened to harm them if they did not leave.[12]

Remains and commemorations of the Dorsland Trek

- In Kaokoland, several ruins of temporary settlements are still visible, including a Dopper church (Dopper (English: Baptist) is an informal name for the Gereformeerde Kerke) near Kaoko Otavi.[13]

- Outside Swartbooisdrift the Dorsland Trekkers Monument has been erected to commemorate the journey.[13]

- At Cassinga there is a memorial obelisk, erected in 2003, commemorating those who died during the trek.[14]

- At Humpata there is a large obelisk, erected in 1958 commemorating the Trekkers, and there are several graves of the settlers, including that of their leader, Gert Alberts.[13]

- The Dorsland tree in the remote east of Namibia bears a carving "1883", created when the tree was temporary shelter

Notable Dorsland trekkers

References

- Deon Lamprecht (27 January 2015). Tannie Pompie se oorlog: In die Driehoek van die Dood. Tafelberg. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-624-05420-7.

- Joubert, Bruce. "An historical perspective on animal power use in South Africa" (PDF). Animal Traction Network for Eastern and Southern Africa.

- "The Dorsland Trekkers". tourbrief.com. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- "The first group of Dorslandtrekkers (Thirstland trekkers), under leadership of Gert Alberts, leaves Pretoria". South African History Online. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- "The Dorsland Trek 4x4 Route". NamibWeb. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- Dana Snyman (23 September 2013). Onder die radar: Stories uit ons land. Tafelberg. pp. 173–. ISBN 978-0-624-06228-8.

- G. Clarence-Smith: The thirstland trekkers in Angola – Some reflections on a frontier society.

- Mary Rice; Craig Gibson (2001). Heat, Dust, and Dreams: An Exploration of People and Environment in Namibia's Kaokoland and Damaraland. Struik. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-1-86872-632-5.

- Stassen, Nicol. The Boers in Angola, 1928–1975. "Part III." Pretoria: Protea Book House, 2011. 123-25. Print.

- Bender, Gerald J. Angola under the Portuguese: The Myth and the Reality. Berkeley: U of California, 1978. Print.

- Mashuna, Timotheus (2 March 2012). "Kambazembi Wa Kangombe: The Influential and Peace-Loving Herero Chief (1846–1903)". New Era. Archived from the original on 21 February 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Shiremo, Shampapi (14 January 2011). "Captain Andreas Lambert: A brave warrior and a martyr of the Namibian anti-colonial resistance". New Era. Archived from the original on 8 December 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- "Dorsland Gedenkfees" [Thirstland commemoration] (in Afrikaans). Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- Mongudhi, Tileni (12 June 2015). "Cassinga forgotten". The Namibian.

External links

- Wilkinsons World Picture of the Dorsland Trekkers Monument