Tlazōlteōtl

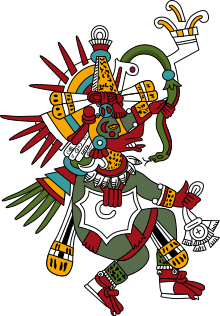

In Aztec mythology, Tlazolteotl (or Tlaçolteotl, Classical Nahuatl: Tlahzolteōtl, pronounced [tɬaʔsoɬˈtéo:tɬ]) is a deity of vice, purification, steam baths, lust, filth, and a patroness of adulterers. She is known by three names, Tlahēlcuāni ("she who eats tlahēlli or filthy excrescence [sin]") and Tlazōlmiquiztli ("the death caused by lust"), and Ixcuina or Ixcuinan (Huastec: Ix Cuinim, Deity of Cotton), the latter of which refers to a quadripartite association of four sister deities.[1][2][3]

Tlazōlteōtl is the deity for the 13th trecena of the sacred 260-day calendar Tōnalpōhualli, the one beginning with the day Ce Ōllin, or First Movement. She is associated with the day sign of the jaguar.[4]

Tlazolteotl played an important role in the confession of wrongdoing through her priests.[5]

Aztec religion

Tlazolteotl may have originally been a Huaxtec deity from the Gulf Coast[6] who would have been assimilated into the Aztec pantheon.

Quadripartite Deities

Under the name of Ixcuinan she was thought to be quadrupartite, composed of four sisters of different ages known by the names Tiyacapan (the first born), Tēicuih (the younger sister, also Tēiuc), Tlahco (the middle sister, also Tlahcoyēhua) and Xōcotzin (the youngest sister). When conceived of as four individual deities, they were called ixcuinammeh or tlazōltēteoh;[2][3] individually, they were deities of luxury.[7]

Sin

Encouragement of Sin

According to Aztec belief, it was Tlazolteotl who inspired vicious desires and who likewise forgave and cleaned away sin.[8] She was also thought to cause disease, especially STDs. It was said that Tlazolteotl and her companions would afflict people with disease if they indulged themselves in forbidden love.[9] The uncleanliness was considered both on a physical and moral level and could be cured by steam bath, a rite of purification, or calling upon the Tlazōltēteoh, the deities of love and desires.[9]

Purification

For the Aztecs there were two main deities thought to preside over purification: Tezcatlipoca, because he was thought to be invisible and omnipresent, therefore seeing everything; and Tlazolteotl, the deity of lechery and unlawful love.[8] It is said that when a man confessed before Tlazolteotl everything was revealed. Purification with Tlazolteotl would be done through a priest. One could only receive the "mercy" once in their life which is why the practice was most common among the elderly.[10]

.jpg)

The priest (tlapouhqui) would be consulted by the penitent and would consult the 260-day ritual calendar (tonalpohualli) to determine the best day and time for the purification to take place. On the day of, he would listen to the sins confessed and then render judgment and penance, ranging from fasts to presentation of offerings and ritual song and dance, depending on the nature and the severity of the sin.[12]

Dirt eating

Tlazōlteōtl was called "Deity of Dirt" (Tlazōlteōtl) and "Eater of Ordure" (Tlahēlcuāni, 'she who eats dirt [sin]') with her dual nature of deity of dirt and also of purification. Sins were symbolized by dirt. Her dirt-eating symbolized the ingestion of the sin and in doing so purified it.[13][14] She was depicted with ochre-colored symbols of divine excrement around her mouth and nose.[14] In the Aztec language the word for sacred, tzin, comes from tzintli, the buttocks, and religious rituals include offerings of "liquid gold" (urine) and "divine excrement", which Klein jocularly translated to English as "holy shit".[14][15] Through this process, she helped create harmony in communities.[14]

Festival

Tlazōlteōtl was one of the primary Aztec deities celebrated in the festival of Ochpaniztli (meaning "sweeping") that was held September 2–21 to recognize the harvest season. The ceremonies conducted during this timeframe included ritual cleaning, sweeping, and repairing, as well as the casting of corn seed, dances, and military ceremonies.[16]

Gallery

The moons represent the cyclical nature of sin and purification, and the animal motifs serve to ground the deity in the earth and indicate fertility.[17]

The moons represent the cyclical nature of sin and purification, and the animal motifs serve to ground the deity in the earth and indicate fertility.[17] Drawing from the Codex Borgia

Drawing from the Codex Borgia Another drawing from the Codex Borgia

Another drawing from the Codex Borgia

See also

Notes

- Soustelle, p. 104, 199

- Sahagun, Florentine codex book 1, p. 23

- Sullivan, p. 12

- Sullivan p. ?

- Sahagun p. 8-9

- Miller & Taube, p. 168

- Sahagun p. 8

- Soustelle, p. 199

- Soustelle, p. 193

- Sahagun p. 11

- Townsend, p. 115

- Sahagun p. 10-11

- Sullivan, Thelma D. (1982). Tlazolteotl-Ixcuina: The Great Spinner and Weaver. p. 15.

- Gonzales, Patrisia (2012). Red Medicine: Traditional Indigenous Rites of Birthing and Healing. pp. 98–99.

Klein reinterprets the ochre color symbols found around the mouth and nose of some Tlazolteotl depictions, as well as painted to represent matter emanating from the buttocks — from connoting 'dirt' to 'divine excrement.' She notes that tlazōlli — interpreted by many academics as Tlazolteotl's root word — is not only excrement or something old or used. Similarly the word for 'venerable' is tzin, which comes from tzintli, the buttocks. Urine as 'liquid gold' and offerings of excrement are examples of 'divine excrement' or, as Klein writes playfully, 'Holy Shit'.

- Klein, Cecelia F. (1993). "Teocuitlatl, 'Divine Excrement': The Significance of 'Holy Shit' in Ancient Mexico". Art Journal. 52 (3): 20–27.

- Townsend, p. 221

- Townsend p. 115

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tlazōlteōtl. |

- Soustelle, J., (1961) The Daily life of the Aztecs, London, WI

- An Illustrated Dictionary of the Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya, by Mary Miller & Karl Taube Publisher: Thames & Hudson (April 1997)

- Bernardino de Sahagun, 1950–1982, Florentine Codex: History of the Things of New Spain, translated and Edited by Arthur J.O. Anderson and Charles Dibble, Monographs of the school of American research, no 14. 13. parts Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press

- Townsend, R.F., (2000) The Aztecs Revised Edition, Thames & Hudson Ltd, London

- Sullivan, T. “Tlazolteotl-Ixcuina: The Great Spinner and Weaver”. The Art and Iconography of late post-Classic Mexico, Ed. Elizabeth Hill Boone. Dumbarton Oaks, Washington DC. pp. 7–37.