Centeōtl

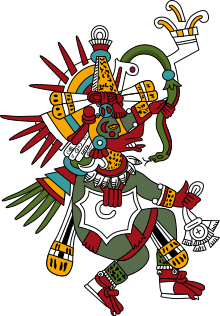

In Aztec mythology, Centeōtl [senˈteoːt͡ɬ] (also known as Centeocihuatl or Cinteotl) is the maize deity. Cintli [ˈsint͡ɬi] means "dried maize still on the cob" and teōtl [ˈteoːt͡ɬ] means "deity".[1] According to the Florentine Codex,[2] Centeotl is the son of the earth goddess, Tlazolteotl and solar deity Piltzintecuhtli, the planet Mercury. Born on the day-sign 1 Xochitl.[3][4] Another myth claims him as the son of the goddess Xochiquetzal.[5] The majority of evidence gathered on Centeotl suggests that he is usually portrayed as a young man (although a debate is still ongoing), with yellow body colouration.[2] Some specialists believe that Centeotl used to be the maize goddess Chicomecōātl. Centeotl was considered one of the most important deities of the Aztec era. There are many common features that are shown in depictions of Centeotl. For example, there often seems to be maize in his headdress. Another striking trait is the black line passing down his eyebrow, through his cheek and finishing at the bottom of his jaw line. These face markings are similarly and frequently used in the late post-classic depictions of the 'foliated' Maya maize god.

Controversy

According to sources Cinteotl is the god of maize and subsistence[6] and Centeotl[7] corresponds to Chicomecoatl,[8] the goddess of agriculture.

Worship

In the Tonalpohualli (a 260-day sacred calendar used by many ancient Mesoamerican cultures), Centeotl is the Lord of the Day for days with number seven and he is the fourth Lord of the Night. In Aztec mythology, maize (which was called Cintli in Nahuatl, the Aztec spoken language) was brought to this world by Quetzalcoatl and it is associated with the group of stars known commonly today as the Pleiades.[9]

At the beginning of the year (most likely around February time), Aztec workers would plant the young maize. These young maize plants potentially were used as symbolism for a pretty goddess, most likely Chicomecōātl, Princess of the Unripe Maize. Chicomecōātl is usually depicted carrying fresh maize in her hands, bare-breasted and sitting down in a modest manner. An interesting conflict exists in that some historians believe Chicomecōātl, otherwise known as 'the hairy one' and Centeotl are the same deity. When the seeds were planted, a ritual dance occurred in order to thank Mother Earth and more specifically Centeotl. These dances became increasingly more prominent as the warmth of the sun brought about great prosperity for the Aztecs in the form of sprouting maize canes. This festival has been compared to the more Western maypole festival due to the similarity of their celebrations (dancing for spring, feasting, etc.)over generalized. These festivals were probably very pleasant for the Aztecs, judging by similar festivals in other civilizations(not an academic comparison). A major custom in Mexico during this festival period was for female Aztecs, regardless of marital status to loosen their ponchos and let down their hair. They would proceed to dance bare-breasted in the maize fields in order to thank Centeotl for his work. Then each female would pick five ears of corn from the field and bring it back in a grand procession while singing and dancing. Women in these processions were the promises of food and life in the Aztec world. Traditionally massive fights would break out as people tried to soak one another in flower pollen or scented maize flour. Also flower petals were thrown in ceremonial fashion over people who were carrying the ears of corn.[10]

Corn was rather essential to Aztec life and thus the importance of Centeotl cannot be overlooked. It can be seen from countless historical sources that a lot of the maize that was cultivated by the Aztecs was used in sacrifices to Gods. Usually at least five newly ripened maize cobs were picked by the older Aztec women. These were then carried on the female's backs after being carefully wrapped up, somewhat like a mother would wrap up a newborn child. Once the cobs reached their destination, usually outside a house, they were placed in a special corn basket and would stay there until the following year. This was meant to represent the resting of the maize spirits until the next harvesting period came around.[10]

These five cobs were also symbols for a seemingly separate goddess.[7] This highly worshipped goddess was known as Lady Chicomecoatl, Seven Serpents.[7] She was the earth spirit and the lady of fertility and life, seen as a kind of mother figure in the Aztec world and was the partner of Centeotl.[10]

_(14803957783).jpg) Photo from The myths of Mexico and Peru published 1902

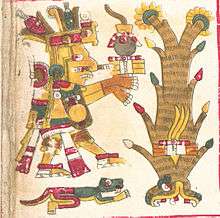

Photo from The myths of Mexico and Peru published 1902 Cinteotl, dieu du maïs, devant le royaume des morts (Codex Fejérváry-Mayer, page 11)

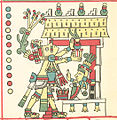

Cinteotl, dieu du maïs, devant le royaume des morts (Codex Fejérváry-Mayer, page 11) Cinteotl, dieu du maïs (Codex Fejérváry-Mayer, page 34)

Cinteotl, dieu du maïs (Codex Fejérváry-Mayer, page 34) Page 13 of the Codex Borbonicus Tlazolteotl, who is portrayed wearing a flayed skin, giving birth to Cinteotl

Page 13 of the Codex Borbonicus Tlazolteotl, who is portrayed wearing a flayed skin, giving birth to Cinteotl from the Codex Rios

from the Codex Rios

See also

- Maya maize god

- Chicomecōātl (Aztec goddess of maize)

References

- Nahuatl Dictionary. (1997). Wired Humanities Project. University of Oregon. Retrieved September 1, 2012, from link

- . Miller, The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya (London: Thames and Hudson, 1993) p62

- Hombres de Maíz. Miguel Angel Asturias p 398

- Codex Vaticanus No. 3773 (Codex Vaticanus B) Eduard Seler p 101

- Markman, Roberta H., Peter T. (1994). The Flayed God: The Mesoamerican Mythological Tradition. Harpercollins. ISBN 0-06-250749-4.

- Cecilio Agustín Robelo (1905). Biblioteca Porrúa. Imprenta del Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Historia y Etnología (ed.). Diccionario de Mitología Nahua (in Spanish). México. pp. 86, 87. ISBN 978-9684327955.

- Cecilio Agustín Robelo (1905). Biblioteca Porrúa. Imprenta del Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Historia y Etnología (ed.). Diccionario de Mitología Nahua (in Spanish). México. pp. 71, 72. ISBN 978-9684327955.

- Cecilio Agustín Robelo (1905). Biblioteca Porrúa. Imprenta del Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Historia y Etnología (ed.). Diccionario de Mitología Nahua (in Spanish). México. pp. 141, 142. ISBN 978-9684327955.

- Centeotl, the Lord of Maize

- C.Burland, The Aztecs: Gods and Fate in Ancient Mexico (London: Orbis, 1980) p39.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Centeotl. |