Timeline of plague

Key developments

| Time period | Key developments |

|---|---|

| 3500–3000 BC (circa) | In 2018 a Swedish tomb was excavated and discovered to harbor evidence of Yersinia pestis within the interred human remains. The estimated date of this individual's death is correlated to a period of European history known as the Neolithic decline; the presence of plague in the remains is evidence for the plague as a potential cause of this event.[1][2][3] |

| 541–750 (circa) | The first plague pandemic spreads from Egypt to the Mediterranean (starting with the Plague of Justinian) and Northwestern Europe.[4] |

| 1346–1840 | The second plague pandemic spreads from China (questionable) to the Mediterranean and Europe.[4] The Black Death of 1346–1353 is considered to be unparalleled in human history.[5][6] From 1347 to 1665, the Black Death is responsible for about a million of deaths in Europe.[7] |

| 1866–1960s | The third plague pandemic, which originated in China, results in about 2.2 million deaths.[7] The plague spread to India and killed a total of 22.5 million people under the British rule. Haffkine develops the first vaccine against bubonic plague.[8] Antibiotic drugs are developed in the 1940s which dramatically reduce the death rate from plague.[9] |

| 1950–2000 | Plague cases are massively reduced during the second half of the 20th century. However, outbreaks would still occur, especially in developing countries. Between 1954 and 1997, human plague is reported in 38 countries, making the disease a remerging threat to human health.[7] Also, between 1987 and 2001, 36,876 confirmed cases of plague with 2,847 deaths are reported to the World Health Organization.[10] |

| Recent years | In the 21st century, fewer than 200 people die of the plague worldwide each year, mainly due to lack of treatment.[11] Plague is considered to be endemic in 26 countries around the world, with most cases found in remote areas of Africa.[12] The three most endemic countries are Madagascar, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Peru.[13] |

Graphs of modern outbreaks

Cases of human plague for the period 1994–2003 in countries that reported at least 100 confirmed or suspected cases. Case-fatality rates in % are represented on the left vertical.[14]

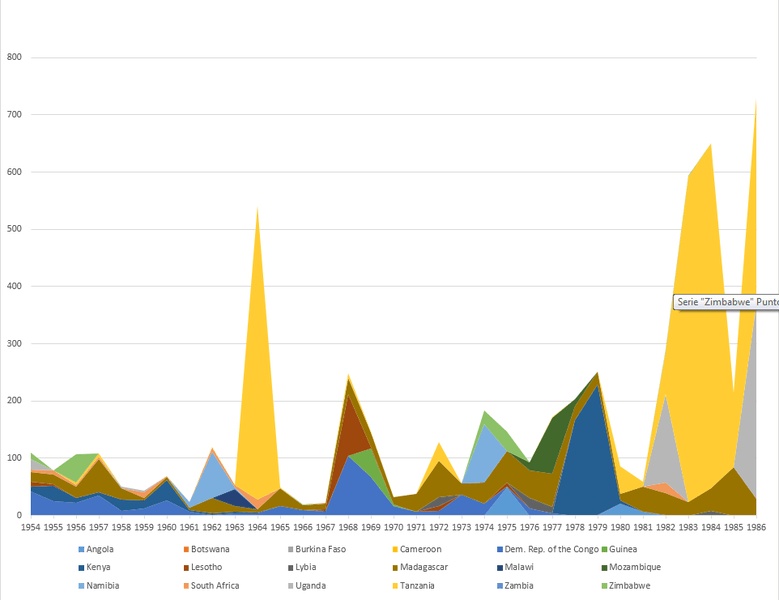

Cases of human plague for the period 1994–2003 in countries that reported at least 100 confirmed or suspected cases. Case-fatality rates in % are represented on the left vertical.[14] Plague cases reported in Africa to the World Health Organization for the period 1954–1986. Cumulative.[15]

Plague cases reported in Africa to the World Health Organization for the period 1954–1986. Cumulative.[15] Plague cases reported in Americas to the World Health Organization for the period 1954–1986. Cumulative.[15]

Plague cases reported in Americas to the World Health Organization for the period 1954–1986. Cumulative.[15] Plague cases reported in Asia to the World Health Organizations for the period 1954–1986. Cumulative.[15]

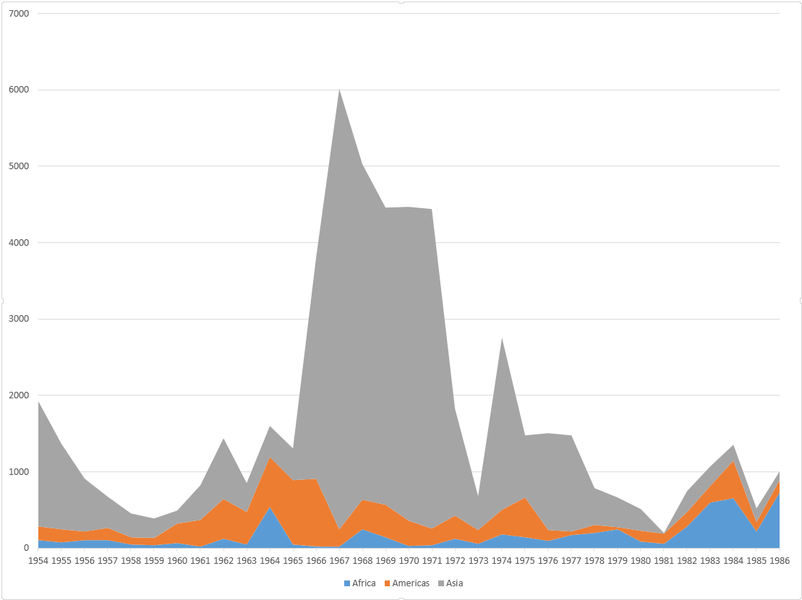

Plague cases reported in Asia to the World Health Organizations for the period 1954–1986. Cumulative.[15] Plague cases reported to the World Health Organization by continent. Cumulative.[15]

Plague cases reported to the World Health Organization by continent. Cumulative.[15]

Full timeline

| Year/Period | Event type | Event | Present-day geographic location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 430 BC | Epidemic | Plague of Athens devastates the city's population. The outbreak originated in Ethiopia and spread to the Mediterranean region through Egypt and Libya.[16] | Greece, Mediterranean basin |

| 224 BC | Plague infection is first recorded in China.[17] | China | |

| 165–180 AD | Epidemic | Antonine Plague, also known as the plague of Galen, the Greek physician living in the Roman Empire who described it. It is suspected to have been smallpox or measles. The total deaths have been estimated at five million and the disease killed as much as one-third of the population in some areas and devastated the Roman army. | Iraq, Italy, France, Germany |

| 250–270 AD | Epidemic | Plague of Cyprian breaks out in Rome. It is estimated to kill about 5000 people a day.[16] | Italy |

| 540 AD | Epidemic | Plague epidemic originates in Ethiopia spreads to Pelusium in Egypt.[18] | Ethiopia, Egypt |

| 541–542 AD | Epidemic | The Plague of Justinian, considered the first recorded pandemic, breaks out and develops as an extended epidemic in the Mediterranean basin. According to some, frequent outbreaks over the next two hundred years would eventually kill an estimated 25 million people.[7][19] This number has recently been disputed.[20] | Mediterranean Basin |

| 542 AD | Epidemic | The plague arrives in Constantinople (now Istanbul). By spring of 542, about 5,000 deaths per day in the city are calculated, although some estimates vary to 10,000 per day. The epidemic would go on to kill over a third of the city's population.[18] | Turkey |

| 543 AD | Epidemic | After passing from Italy to Syria, Palestine, and Iraq, plague reaches Iran.[10] | Iran |

| 627 AD | Epidemic | A large epidemic of plague breaks out in Ctesiphon, the capital of the Sasanian Empire, killing more than 100,000 people.[10] | Iran |

| 1334 | Epidemic | The second plague pandemic breaks out in China (questionable). Widely known as the "Black Death" or the Great Plague, it is regarded as one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, resulting in the deaths of an estimated 75 to 200 million people in Eurasia.[19][6] | Eurasia |

| 1338–1339 | Bubonic plague is reported in central Asia.[21] | ||

| 1345 | Plague occurs in southern Russia, around the lower Volga River basin.[22][23] | Russia | |

| 1346 | Epidemic | Bubonic plague breaks out in India (questionable).[21] | China, India |

| 1347 | Epidemic | The plague spreads to Constantinople, a major port city. It also infects the Black Sea port of Kaffa down from southern Russia.[23][21] | Turkey, Ukraine |

| 1347 | Epidemic | Italian traders bring the plague in rat-infested ships from Constantinople to Sicily, which becomes the first place in Europe to suffer the Black death epidemic. The same year, Venice is also hit.[11] | Italy |

| 1347–1350 | Medical development | During the 1347–1350 outbreak, doctors are completely unable to prevent or cure the plague. Some of the cures they try include cooked onions, ten-year-old treacle, arsenic, crushed emeralds, sitting in the sewers, sitting in a room between two enormous fires, fumigating the house with herbs, trying to stop God punishing the sick for their sin. Flagellants would go on processions whipping themselves.[24] | Europe |

| 1348 | Medical development | Italian writer Giovanni Boccaccio in his book Decameron writes a description of symptoms of the plague.[18] | Italy |

| 1348–1350 | Epidemic | The Black Death arrives at Melcombe Regis in the south of England. Over the next year, the plague spreads into Northern England, Wales and Ireland. By 1350, the plague reaches Scotland. The estimated death toll for the British Isles is calculated at 3.2 million.[25] | United Kingdom, Ireland |

| 1349 | Genocide | Black Death Jewish persecutions. A rumor rises claiming that Jews are responsible for the plague as an attempt to kill Christians and dominate the world. Supported by a widely distributed report of the trial of Jews who supposedly had poisoned wells in Switzerland, the rumor spreads quickly. As a result, a wave of pogroms against Jews breaks out. Christians start to attack Jews in their communities, burning their homes, and murder them with clubs and axes. In the Strasbourg massacre, it is estimated that people locked up and burned 900 Jews alive. Finally, Pope Clement VI issues a religious order to stop the violence against the Jews, claiming that the plague is "the result of an angry God striking at the Christian people for their sins."[11] | France, Switzerland |

| 1351 | Epidemic | Black Death epidemic reaches Russia, attacking Novgorod and reaching Pskov, before being temporarily suppressed by the Russian winter.[5] | Russia |

| 1352 | Epidemic | The plague reaches Moscow.[5] | Russia |

| 1361–1364 | Medical development | During an outbreak, doctors learn how to help the patient recover by bursting the buboes.[24] | |

| 1374 | Epidemic | Black Death epidemic re-emerges in Europe. In Venice, various public health controls such as isolating victims from healthy people and preventing ships with disease from landing at port are instituted.[18] | Europe |

| 1377 | Program launch | The Republic of Ragusa establishes a landing station for vessels far from the city and harbour in which travellers suspected to have the plague must spend thirty days, to see whether they became ill and died or whether they remained healthy and could leave.[18] | Croatia |

| 1403 | After finding thirty days isolation to be too short, Venice dictates that travellers from the Levant in the eastern Mediterranean be isolated in a hospital for forty days, the quarantena or quaranta giorni, from which the term quarantine is derived.[18] | Italy | |

| 1582–1583 | Epidemic | A new outbreak of bubonic plague occurs, in the Canary Islands, mainly affecting the city of San Cristóbal de La Laguna on the island of Tenerife. Between 5,000 and 9,000 people die, a considerable number considering that the population of the island at the time was less than 20,000 inhabitants.[26][27][28] | Spain |

| 1629–1631 | Epidemic | The Italian plague of 1629–1631 develops as a series of outbreaks of bubonic plague. About 280,000 people are estimated to be killed in Lombardy and other territories of Northern Italy.[29] The Italian plague is estimated to have claimed between 35 and 69 percent of the local population.[17] | Italy |

| 1637 | Epidemic | Plague breaks out in Andalusia, killing about 20,000 people in less than four months.[30] | Spain |

| 1647–1652 | Epidemic | Plague ravages Spain. About 30,000 die in Valencia. The great Plague of Seville breaks out.[30] | Spain |

| 1665–1666 | Epidemic | Great Plague of London. 100,000 people are killed within 18 months.[31] | United Kingdom |

| 1679 | Epidemic | The Great Plague of Vienna kills at least 76,000 people.[32] | Austria |

| 1720 | Epidemic | The Great Plague of Marseille kills more than 100,000 people in the French city of Marseille. | Marseille, France |

| 1722 | Publication | Daniel Defoe publishes A Journal of the Plague Year, a fictional account of the Great Plague of London in 1665. This novel is often read as non-fiction.[33] | United Kingdom |

| 1738 | Epidemic | Great Plague of 1738 kills at least 36,000 people.[34] | Romania, Hungary, Ukraine, Serbia, Croatia, Austria |

| 1772–1850 | Epidemic | The human plague is reported intermittently in the Chinese province of Yunnan, where the third plague pandemic would begin in the 1860s.[7][35] | China |

| 1867 | Epidemic | The plague spreads from Yunnan Province to Beihai on the Chinese coastline.[7] | China |

| 1869 | Epidemic | The plague is observed in Taiwan.[7] | Taiwan |

| 1894 | Epidemic | The plague spreads to Guangdong and results in the death of about 70,000 people.[36][7] | China |

| 1894 | Scientific development | Working independently, both French bacteriologist Alexandre Yersin and Japanese bacteriologist Shibasaburo Kitasato isolate the bacterium that causes bubonic plague. Yersin discovers that rodents are the mode of infection. The bacterium is named yersinia pestis after Yersin.[7][18] | |

| 1896–1897 | Medical development | Russian bacteriologist Waldemar Haffkine successfully protects rabbits against an inoculation of virulent plague microbes, by treating them previously with a subcutaneous injection of a culture of the microbes in broth. The first vaccine for bubonic plague is developed. The rabbits treated in this way become immune to plague. In the next year, Haffkine causes himself to be inoculated with a similar preparation, thus proving in his own person the harmlessness of the fluid. This is considered the first vaccine against bubonic plague.[8] | India (Bombay) |

| 1899 | Epidemic | Plague is first introduced in Latin America in Paraguay, followed by Brazil and Argentina in the same year.[12] | Paraguay, Brazil, Argentina |

| 1901 | Epidemic | Plague infection is first reported in Uruguay.[12] | Uruguay |

| 1902 | Epidemic | Plague infection is first reported in Mexico.[12] | Mexico |

| 1903 | Epidemic | Plague infection is first reported in Chile and Peru.[12] | Chile, Peru |

| 1905 | Epidemic | Plague infection is first reported in Panama.[12] | Panama |

| 1908 | Epidemic | Plague infection is first reported in Ecuador and Venezuela.[12] | Ecuador, Venezuela |

| 1910 | Epidemic | Manchurian plague breaks out, killing about 60,000 people over the course of a year.[37] | China |

| 1912 | Epidemic | Plague infection is first reported in Cuba and Puerto Rico.[12] | Cuba, Puerto Rico |

| 1921 | Epidemic | Plague infection is first reported in Bolivia.[12] | Bolivia |

| 1924–1925 | Epidemic | Plague breaks out in Los Angeles. 32 people get infected and only 2 survive. It is the last rat-borne epidemic occurring in the United States.[38] | United States |

| 1928 | Medical development | Antibiotics developed | United Kingdom |

| 1947 | Publication | French novelist Albert Camus publishes The Plague, a novel about a fictional outbreak of plague in Oran, Algeria. The book helps to show the effects the plague has on a populace.[39] | France |

| 1994 | Epidemic | Plague in India. The country experiences a large outbreak of pneumonic plague after 30 years with no reports of the disease. 693 suspected bubonic or pneumonic plague cases are reported.[10][40] | India |

| 1995–1998 | Epidemic | From 1995 to 1998, annual outbreaks of plague were witnessed in Mahajanga, Madagascar.[41] | Madagascar |

| 2003 | Epidemic | An outbreak of plague is reported in Algeria, in an area considered plague-free for 50 years.[10] | Algeria |

| 2006 | Epidemic | In June 2006, one hundred deaths resulting from pneumonic plague were reported in Ituri district of the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Control of the plague was proving difficult due to the ongoing conflict.[42] | Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| 2009 | Infection | Plague is reported in Libya, after 25 years without a case of the disease.[10] | Libya |

| 2014 | Scientific development | Researchers at Duke University School of Medicine and Duke-NUS Medical School Singapore find the Yersinia pestis bacteria to hitchhike on immune cells in the lymph nodes and eventually ride into the lungs and the blood stream, thus spreading bubonic plague effectively to others. | Singapore |

| 2014–2018 | Epidemic | Outbreaks in Madagascar | Madagascar |

gollark: !time <@677461592178163712>

gollark: !time

gollark: is basically chromium now

gollark: Your use of chrome and your complaininining about Firefø»«.

gollark: You are just a silly triangle.

References

- "Britain's prehistoric catastrophe revealed: How 90% of the neolithic population vanished in just 300 years". independent.co.uk. 2018-02-21. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- "Ancient, Unknown Strain of Plague Found in 5,000-Year-Old Tomb in Sweden". livescience.com. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- Leitch, Carmen. "The Plague May Have led to the Decline of Neolithic Settlements". labroots.com. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- Byrne, Joseph Patrick (2012). Encyclopedia of the Black Death. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. xxi. ISBN 978-1598842531.

- "The Black Death: The Greatest Catastrophe Ever". historytoday.com. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- Wade, Nicholas (31 October 2010), Europe's Plagues Came From China, Study Finds, The New York Times, retrieved 12 May 2020

- Xu, Lei; Liu, Qiyong; Stige, Leif Chr.; Ben Ar, Tamara; Fang, Xiye; Chan, Kung-Sik; Wang, Shuchun; Stenseth, Nils Chr.; Zhang, Zhibin (2011). "Nonlinear effect of climate on plague during the third pandemic in China". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (25): 10214–10219. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10810214X. doi:10.1073/pnas.1019486108. PMC 3121851. PMID 21646523.

- Hawgood, Barbara J (2007). "Waldemar Mordecai Haffkine, CIE (1860–1930): prophylactic vaccination against cholera and bubonic plague in British India" (PDF). jameslindlibrary.org. 15: 9–19. doi:10.1258/j.jmb.2007.05-59. PMID 17356724. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- "Achievements in Public Health, 1900–1999: Control of Infectious Diseases". cdc.gov. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- Shahraki, Abdolrazagh Hashemi; Carniel, Elizabeth; Mostafavi, Ehsan (2016). "Plague in Iran: its history and current status". Epidemiology and Health. 38: e2016033. doi:10.4178/epih.e2016033. PMC 5037359. PMID 27457063.

- "The 'Black Death': A Catastrophe in Medieval Europe". Constitutional Rights Foundation. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- Schneider, Maria Cristina; Najera, Patricia; Aldighieri, Sylvain; Galan, Deise I.; Bertherat, Eric; Ruiz, Alfonso; Dumit, Elsy; Gabastou, Jean Marc; Espinal, Marcos A. (2014). "Where Does Human Plague Still Persist in Latin America?". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 8 (2): e2680. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002680. PMC 3916238. PMID 24516682.

- "Plague". WHO. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- Butler, Thomas (2009). "Plague into the 21st Century". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 49 (5): 736–742. doi:10.1086/604718. PMID 19606935. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- "WHO Report on Global Surveillance of Epidemic-prone Infectious Disease" (PDF). WHO. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- Kercheval, Howard. "One of the big-league diseases of all time". United Press International. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- "Epidemics of the Past". infoplease.com. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- Frith, John. "The History of Plague – Part 1. The Three Great Pandemics". Journal of Military and Veterans' Health. ISSN 1839-2733. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- "History". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- Mordechai, Lee; Eisenberg, Merle; Newfield, Timothy P.; Izdebski, Adam; Kay, Janet E.; Poinar, Hendrik (2019-12-02). "The Justinianic Plague: An inconsequential pandemic?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (51): 25546–25554. doi:10.1073/pnas.1903797116. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6926030. PMID 31792176.

- "The Black Plague: The Least You Need to Know". web.cn.edu. Carson-Newman University. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- Mansbach, Richard W.; Taylor, Kirsten L. (2013-06-17). Introduction to Global Politics. ISBN 9781136517389. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- Schmid, Boris V.; Büntgen, Ulf; Easterday, W. Ryan; Ginzler, Christian; Walløe, Lars; Bramanti, Barbara; Stenseth, Nils Chr. (2015). "Climate-driven introduction of the Black Death and successive plague reintroductions into Europe". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (10): 3020–3025. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.3020S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1412887112. PMC 4364181. PMID 25713390.

- "The Black Death". BBC. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- "Course of the Black Death". BBC. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- La Peste. El cuarto jinete

- Las epidemias de la Historia: la peste en La Laguna (1582-1583)

- La terrible epidemia de peste en La Laguna en 1582

- Kohn, George C. (2007). Encyclopedia of Plague and Pestilence: From Ancient Times to the Present. ISBN 9781438129235. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- Kohn, George C. (2007). Encyclopedia of Plague and Pestilence: From Ancient Times to the Present. ISBN 9781438129235. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- "The Great Plague of London, 1665". Contagion, Historical Views of Diseases and Epidemics. Harvard University. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- Porter, Stephen (2009). The Great Plague. ISBN 9781848680876. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- "A Journal of the Plague Year". Oxford University Press. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- "Demographic Changes". oszk.hu. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- Davis, Lee Allyn (2010-06-23). Natural Disasters. ISBN 9781438118789. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- Wu, Lien-teh; Chun, J. W. H.; Pollitzer, R.; Wu, C. Y. (1936). Plague: a Manual for Medical and Public Health Workers. Shanghai. OCLC 11584901.

- TEH, WU LIEN; CHUN, J. W. H.; POLLITZER., R. (1923). "Clinical Observations upon the Manchurian Plague Epidemic, 1920-21". Manchurian Plague Prevention Service, China. 21 (3): 289–306. PMC 2167336. PMID 20474781.

- Kellogg, W. H. (1935). "The Plague Situation". American Journal of Public Health and the Nation's Health. 25 (3): 319–322. doi:10.2105/ajph.25.3.319. PMC 1559064. PMID 18014177.

- "Albert Camus' The Plague: a story for our, and all, times". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- cdc.gov. "International Notes Update: Human Plague -- India, 1994". Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- Boisier, Pascal; Rahalison, Lila; Rasolomaharo, Monique; Ratsitorahina, Maherisoa; Mahafaly, Mahafaly; Razafimahefa, Maminirana; Duplantier, Jean-Marc; Ratsifasoamanana, Lala; Chanteau, Suzanne (2002). "Epidemiologic Features of Four Successive Annual Outbreaks of Bubonic Plague in Mahajanga, Madagascar". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 8 (3): 311–16. doi:10.3201/eid0803.010250. PMC 2732468. PMID 11927030.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Congo 'plague' leaves 100 dead". BBC News. June 14, 2006. Retrieved December 15, 2006.

This article is issued from Wikipedia. The text is licensed under Creative Commons - Attribution - Sharealike. Additional terms may apply for the media files.