Thermochemistry

Thermochemistry is the study of the heat energy which is associated with chemical reactions and/or physical transformations. A reaction may release or absorb energy, and a phase change may do the same, such as in melting and boiling. Thermochemistry focuses on these energy changes, particularly on the system's energy exchange with its a surroundings. Thermochemistry is useful in predicting reactant and product quantities throughout the course of a given reaction. In combination with entropy determinations, it is also used to predict whether a reaction is spontaneous or non-spontaneous, favorable or unfavorable.

Endothermic reactions absorb heat, while exothermic reactions release heat. Thermochemistry coalesces the concepts of thermodynamics with the concept of energy in the form of chemical bonds. The subject commonly includes calculations of such quantities as heat capacity, heat of combustion, heat of formation, enthalpy, entropy, free energy, and calories.

History

Thermochemistry rests on two generalizations. Stated in modern terms, they are as follows:[1]

- Lavoisier and Laplace's law (1780): The energy change accompanying any transformation is equal and opposite to energy change accompanying the reverse process.[2]

- Hess' law (1840): The energy change accompanying any transformation is the same whether the process occurs in one step or many.

These statements preceded the first law of thermodynamics (1845) and helped in its formulation.

Lavoisier, Laplace and Hess also investigated specific heat and latent heat, although it was Joseph Black who made the most important contributions to the development of latent energy changes.

Gustav Kirchhoff showed in 1858 that the variation of the heat of reaction is given by the difference in heat capacity between products and reactants: dΔH / dT = ΔCp. Integration of this equation permits the evaluation of the heat of reaction at one temperature from measurements at another temperature.[3][4]

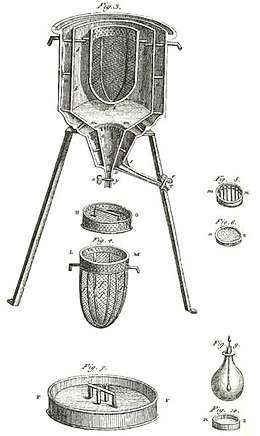

Calorimetry

The measurement of heat changes is performed using calorimetry, usually an enclosed chamber within which the change to be examined occurs. The temperature of the chamber is monitored either using a thermometer or thermocouple, and the temperature plotted against time to give a graph from which fundamental quantities can be calculated. Modern calorimeters are frequently supplied with automatic devices to provide a quick read-out of information, one example being the differential scanning calorimeter (DSC).

Systems

Several thermodynamic definitions are very useful in thermochemistry. A system is the specific portion of the universe that is being studied. Everything outside the system is considered the surroundings or environment. A system may be:

- a (completely) isolated system which can exchange neither energy nor matter with the surroundings, such as an insulated bomb calorimeter

- a thermally isolated system which can exchange mechanical work but not heat or matter, such as an insulated closed piston or balloon

- a mechanically isolated system which can exchange heat but not mechanical work or matter, such as an uninsulated bomb calorimeter

- a closed system which can exchange energy but not matter, such as an uninsulated closed piston or balloon

- an open system which it can exchange both matter and energy with the surroundings,such as a pot of boiling water

Processes

A system undergoes a process when one or more of its properties changes. A process relates to the change of state. An isothermal (same-temperature) process occurs when temperature of the system remains constant. An isobaric (same-pressure) process occurs when the pressure of the system remains constant. A process is adiabatic when no heat exchange occurs.

See also

- Differential scanning calorimetry

- Important publications in thermochemistry

- Isodesmic reaction

- Principle of maximum work

- Reaction Calorimeter

- Thomsen-Berthelot principle

- Julius Thomsen

- Thermodynamic databases for pure substances

- Calorimetry

- Photoelectron photoion coincidence spectroscopy

- Thermodynamics

- Cryochemistry

- Chemical kinetics

References

- Perrot, Pierre (1998). A to Z of Thermodynamics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-856552-6.

- See page 290 of Outlines of Theoretical Chemistry by Frederick Hutton Getman (1918)

- Laidler K.J. and Meiser J.H., "Physical Chemistry" (Benjamin/Cummings 1982), p.62

- Atkins P. and de Paula J., "Atkins' Physical Chemistry" (8th edn, W.H. Freeman 2006), p.56

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 26 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 804–808.