Styxosaurus

Styxosaurus is a genus of plesiosaur of the family Elasmosauridae. Styxosaurus lived during the Campanian age of the Cretaceous period. Two species are known: S. snowii and S. browni.

| Styxosaurus | |

|---|---|

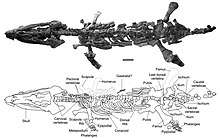

| Fossil neck | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Superorder: | †Sauropterygia |

| Order: | †Plesiosauria |

| Family: | †Elasmosauridae |

| Clade: | †Elasmosaurinae |

| Genus: | †Styxosaurus Welles, 1943 |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Description

Styxosaurus was a large plesiosaur, one of several species of a group collectively called elasmosaurs that appeared in the Late Cretaceous. Elasmosaurs typically have a neck that is at least half the length of the body, and composed of 60-72 vertebrae.

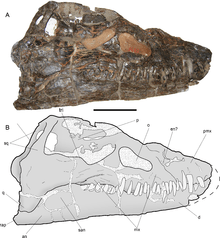

Styxosaurus was around 11 metres (36 ft) long, with about half of the length being composed of its 5.25 metres (17.2 ft) neck.[1] Its sharp teeth were conical and were adapted to puncture and hold rather than to cut; like other plesiosaurs, Styxosaurus swallowed its food whole.[2]

Discovery

The holotype specimen of Styxosaurus snowii was described by S.W. Williston[3][4] from a complete skull and 20 vertebrae.[3]

Another more complete specimen - SDSMT 451 (about 11 metres (36 ft) long) was discovered near Iona, South Dakota, also in the US, in 1945. The specimen was originally described and named Alzadasaurus pembertoni by Welles and Bump (1949) and remained so until it was synonymized with S. snowii by Carpenter.[5] Its chest cavity contained about 250 gastroliths, or "stomach stones". Although it is mounted at the School of Mines as if its head were looking up and out of the water, such a position would be physically impossible.[6]

Styxosaurus is named for the mythological River Styx (Στυξ), which separated the Greek underworld from the world of the living. The -saurus part comes from the Greek sauros (σαυρος), meaning "lizard" or "reptile."

The type specimen was found on Hell Creek in Logan County, Kansas and is the source of the genus name coined by Samuel Paul Welles, who described the genus, in 1943.[7]

Classification

Styxosaurus snowii is from a group called elasmosaurs, and is closely related to Elasmosaurus platyurus, which was found in Kansas, USA, in 1867.[8]

The first Styxosaurus to be described was initially called Cimoliasaurus snowii by S.W. Williston in 1890.[3] The specimen included a complete skull and more than 20 cervical vertebrae ( KUVP 1301) that were found near Hell Creek in western Kansas by Judge E.P. West.[3]

The name was later changed to Elasmosaurus snowii by Williston in 1906[9] and then to Styxosaurus snowii by Welles in 1943.[7]

A second species, Styxosaurus browni, was named by Welles in 1952. Although synonymized with Hydralmosaurus serpentinus in 1999, it has been recently revalidated.[5][10]

The following cladogram shows the placement of Styxosaurus within Elasmosauridae following an analysis by Rodrigo A. Otero, 2016:[11]

| Elasmosauridae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Palaeobiology

While most predators do not use gastroliths for grinding of food, almost all reasonably complete elasmosaur specimens include gastroliths. Although it is possible Styxosaurus may have used the stones as ballast, a Styxosaurus specimen found in the Pierre Shale of western Kansas included ground up fish bones mixed with the gastroliths.[12] In addition, the weight of the gastroliths found in elasmosaur specimens is always much less than 1% of the estimated weight of the living animal.[13]

While crocodiles and some other animals may use gastroliths for ballast today, it appears likely that elasmosaurs used them as a gastric mill. See Henderson (2006) contra Wings (2004).[14]

Styxosaurus, like most other plesiosaurs, probably fed on belemnites, fish (Gillicus, etc.) and squid. With its interlocking teeth, Styxosaurus could grab on to its slippery prey before swallowing it.

References

- O'Gorman, J.P. (2016). "A Small Body Sized Non-Aristonectine Elasmosaurid (Sauropterygia, Plesiosauria) from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia with Comments on the Relationships of the Patagonian and Antarctic Elasmosaurids". Ameghiniana. 53 (3): 245–268. doi:10.5710/AMGH.29.11.2015.2928.

- "National Geiographic "Styxosaurus"". Retrieved 2008-02-21.

- Williston S. W. (1890a). "Structure of the Plesiosaurian Skull". Science. 16 (405): 262. doi:10.1126/science.ns-16.405.262. JSTOR 1766513. PMID 17829759. (text on www.oceansofkansas.com)

- Williston S. W. (1890b). "A New Plesiosaur from the Niobrara Cretaceous of Kansas". Transactions of the Annual Meetings of the Kansas Academy of Science. 12: 174–178. doi:10.2307/3623798. JSTOR 3623798.

- Carpenter, K. 1999. Revision of North American elasmosaurs from the Cretaceous of the western interior. Paludicola 2(2):148-173.

- Everhart, M. J. 2005. Oceans of Kansas - A Natural History of the Western Interior Sea. Indiana University Press.

- Welles, S. P. 1943. Elasmosaurid plesiosaurs with a description of the new material from California and Colorado. University of California Memoirs 13:125-254. figs.1-37., pls.12-29.

- "oceansofkansas.com". Retrieved 2008-02-21.

- Williston S. W. (1906). "North American plesiosaurs: Elasmosaurus, Cimoliasaurus, and Polycotylus". American Journal of Science. Series 4. 21 (123): 221–236. doi:10.2475/ajs.s4-21.123.221.

- Otero RA. (2016) Taxonomic reassessment of Hydralmosaurus as Styxosaurus: new insights on the elasmosaurid neck evolution throughout the Cretaceous. PeerJ 4:e1777 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.1777

- Otero, R. A. (2016). "Taxonomic reassessment of Hydralmosaurus as Styxosaurus: new insights on the elasmosaurid neck evolution throughout the Cretaceous". PeerJ. 4: e1777. doi:10.7717/peerj.1777. PMC 4806632. PMID 27019781.

- Cicimurri, D. J. and M. J. Everhart, 2001. An elasmosaur with stomach contents and gastroliths from the Pierre Shale (late Cretaceous) of Kansas. Kansas Acad. Sci. Trans 104(3-4):129-143.

- Everhart, M. J. 2000. Gastroliths associated with plesiosaur remains in the Sharon Springs Member of the Pierre Shale (Late Cretaceous), western Kansas. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science 103(1-2): 58-69.

- Wings, Oliver (2004): Identification, distribution, and function of gastroliths in dinosaurs and extant birds with emphasis on ostriches (Struthio camelus). Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany, 187 pp. URN: urn:nbn:de:hbz:5N-04626 PDF fulltext Archived 2007-07-16 at Archive.today

Sources

- Everhart, M. J. 2000. Gastroliths associated with plesiosaur remains in the Sharon Springs Member of the Pierre Shale (Late Cretaceous), western Kansas. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science 103(1-2): 58-69.

- Cicimurri, D. J. and M. J. Everhart, 2001. An elasmosaur with stomach contents and gastroliths from the Pierre Shale (late Cretaceous) of Kansas. Kansas Acad. Sci. Trans 104(3-4):129-143.

- Everhart, M. J. 2005a. Oceans of Kansas - A Natural History of the Western Interior Sea. Indiana University Press, 320 pp.

- Everhart, M. J. 2005b. Elasmosaurid remains from the Pierre Shale (Upper Cretaceous) of western Kansas. Possible missing elements of the type specimen of Elasmosaurus platyurus Cope 1868? PalArch 4(3): 19-32.

- Everhart, M. J. 2006. The occurrence of elasmosaurids (Reptilia: Plesiosauria) in the Niobrara Chalk of Western Kansas. Paludicola 5(4):170-183.

- Henderson, J. 2006. Floating point: a computational study of buoyancy, equilibrium, and gastroliths in plesiosaurs. Lethaia 39: 227-244.

- Welles, S. P. 1943. Elasmosaurid plesiosaurs with a description of the new material from California and Colorado. University of California Memoirs 13:125-254. figs.1-37., pls.12-29.

- Welles, S. P. 1952. A review of the North American Cretaceous elasmosaurs. University of California Publications in Geological Sciences 29:46-144. figs. 1-25.

- Welles, S. P. 1962. A new species of elasmosaur from the Aptian of Columbia and a review of the Cretaceous plesiosaurs. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles.

- Welles, S. P. and Bump, J. 1949. Alzadasaurus pembertoni, a new elasmosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of South Dakota. Journal of Paleontology 23(5): 521-535.

- Williston S. W. (1890a). "Structure of the Plesiosaurian Skull". Science. 16 (405): 262. doi:10.1126/science.ns-16.405.262. JSTOR 1766513. PMID 17829759.

- Williston S. W. (1890b). "A New Plesiosaur from the Niobrara Cretaceous of Kansas". Transactions of the Annual Meetings of the Kansas Academy of Science. 12: 174–178. doi:10.2307/3623798. JSTOR 3623798.

- Williston S. W. (1891). "An Interesting Food Habit of the Plesiosaurs". Transactions of the Annual Meetings of the Kansas Academy of Science. 13: 121–122. doi:10.2307/3623988. JSTOR 3623988.

- Williston S. W. (1906). "North American plesiosaurs: Elasmosaurus, Cimoliasaurus, and Polycotylus". American Journal of Science. Series 4. 21 (123): 221–236. doi:10.2475/ajs.s4-21.123.221.

External links

- Styxosaurus at Oceans of Kansas

- Styxosaurus at National Geographic

- Styxosaurus snowii at Sachs Vertebrate Palaeontology Research