Tayra

The tayra (Eira barbara) is an omnivorous animal from the weasel family, native to the Americas. It is the only species in the genus Eira.

| Tayra | |

|---|---|

| |

| A male Tayra, Brazil | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Mustelidae |

| Genus: | Eira Hamilton Smith, 1842 |

| Species: | E. barbara |

| Binomial name | |

| Eira barbara | |

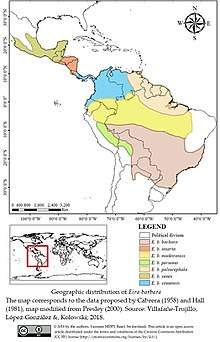

| |

| Tayra range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Mustela barbara Linnaeus, 1758 | |

Tayras are also known as the tolomuco or perico ligero in Central America, motete in Honduras, irara in Brazil, san hol or viejo de monte in the Yucatan Peninsula, and high-woods dog (or historically chien bois) in Trinidad.[2] The genus name Eira is derived from the indigenous name of the animal in Bolivia and Peru, while barbara means "strange" or "foreign".[3]

Description

Tayras are long, slender animals with an appearance similar to that of weasels and martens. They range from 56 to 71 cm (22 to 28 in) in length, not including a 37- to 46-cm-long (15 to 18 in) bushy tail, and weigh 2.7 to 7.0 kg (6.0 to 15.4 lb). Males are larger, and slightly more muscular, than females. They have short, dark brown to black fur which is relatively uniform across the body, limbs, and tail, except for a yellow or orange spot on the chest. The fur on the head and neck is much paler, typically tan or greyish in colour. Albino or yellowish individuals are also known, and are not as rare among tayras as they are among other mustelids.[3]

The feet have toes of unequal length with tips that form a strongly curved line when held together. The claws are short and curved, but strong, being adapted for climbing and running rather than digging. The pads of the feet are hairless, but are surrounded by stiff sensory hairs. The head has small, rounded ears, long whiskers, and black eyes with a blue-green shine. Like most other mustelids, tayras possess anal scent glands, but these are not particularly large, and their secretion is not as pungent as in other species, and is not used in self defence.[3] The species have a unique throat patch that can be used for[4] individual identification.

Range and habitat

Tayras are found across most of South America east of the Andes, except for Uruguay, eastern Brazil, and all but the most northerly parts of Argentina. They are also found across the whole of Central America, in Mexico as far north as southern Veracruz, and on the island of Trinidad.[1] They are generally found in only tropical and subtropical forests, although they may cross grasslands at night to move between forest patches,[5] and they also inhabit cultivated plantations and croplands.[1]

Subspecies

At least seven subspecies are currently recognised:[3]

- E. b. barbara (northern Argentina, Paraguay, western Bolivia and central and southern Brazil)

- E. b. inserta (South Guatemala to central Costa Rica)

- E. b. madeirensis (west Ecuador and northern Brazil)

- E. b. peruana (the eastern Andes in Peru and Bolivia)

- E. b. poliocephala (eastern Venezuela, the Guianas, and northeastern Brazil)

- E. b. senex (central Mexico to northern Honduras)

- E. b. sinuensis (Colombia, western Venezuela, northern Ecuador, and Panama)

Behaviour and diet

Tayras are solitary diurnal animals, although occasionally active during the evening or at night.[5] They are opportunistic omnivores, hunting rodents and other small mammals, as well as birds, lizards, and invertebrates, and climbing trees to get fruit and honey.[3][6] They locate prey primarily by scent, having relatively poor eyesight, and actively chase it once located, rather than stalking or using ambush tactics.[5]

They are expert climbers, using their long tails for balance. On the ground or on large horizontal tree limbs, they use a bounding gallop when moving at high speeds.[7] They can also leap from treetop to treetop when pursued. They generally avoid water, but are capable of swimming across rivers when necessary.[3]

They live in hollow trees, or burrows in the ground. Individual animals maintain relatively large home ranges, with areas up to 24 km2 (9.3 sq mi) having been recorded. They may travel at least 6 km (3.7 mi) in a single night.[3]

An interesting instance of caching has been observed among tayras: a tayra will pick unripe green plantains, which are inedible, and leave them to ripen in a cache, coming back a few days later to consume the softened pulp.[8]

Reproduction

Tayras breed year-round, with the females entering estrus several times each year for 3 to 20 days at a time.[9] Unlike some other mustelids, tayras do not exhibit embryonic diapause, and gestation lasts from 63 to 67 days. The female gives birth to one to three young, which she cares for alone.[3][10]

The young are altricial, being born blind and with closed ears, but are already covered in a full coat of black fur; they weigh about 100 g (3.5 oz) at birth. Their eyes open at 35 to 47 days, and they leave the den shortly thereafter. They begin to take solid food around 70 days of age, and are fully weaned by 100 days. Hunting behaviour begins as early as three months, and the mother initially brings her young wounded or slow prey to practise on as they improve their killing technique. The young are fully grown around 6 months old, and leave their mother to establish their own territory by 10 months.[3]

Conservation

Wild tayra populations are slowly shrinking, especially in Mexico, due to habitat destruction for agricultural purposes. The species is listed as being of least concern.[1]

Gallery

Identified individuals of E. barbara in the Peruvian Amazon

Identified individuals of E. barbara in the Peruvian Amazon Records of E. barbara in the Peruvian Amazon 1 of 2

Records of E. barbara in the Peruvian Amazon 1 of 2 Records of E. barbara in the Peruvian Amazon 2 of 2

Records of E. barbara in the Peruvian Amazon 2 of 2 A tayra from above

A tayra from above

Eira barbara male, Pantanal Brazil

Eira barbara male, Pantanal Brazil

References

- "The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 2018-10-27.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2010-10-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Presley, S.J. (2000). "Eira barbara" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 636: 1–6. doi:10.1644/1545-1410(2000)636<0001:eb>2.0.co;2.

- Villafañe-Trujillo, Álvaro José; López-González, Carlos Alberto; Kolowski, Joseph M. (2018-01-24). "Throat Patch Variation in Tayra (Eira barbara) and the Potential for Individual Identification in the Field". Diversity. 10 (1): 7. doi:10.3390/d10010007.

- Defler, T.R. (1980). "Notes on interactions between tayra (Eira barbara) and the white-fronted capuchin (Cebus albifrons)". Journal of Mammalogy. 61 (1): 156. doi:10.2307/1379979. JSTOR 1379979.

- Galef, B.G.; et al. (1976). "Predation by the tayra (Eira barbara)". Journal of Mammalogy. 57 (4): 760–761. doi:10.2307/1379450. JSTOR 1379450.

- Kavanau, J.L. (1971). "Locomotion and activity phasing of some medium-sized mammals". Journal of Mammalogy. 52 (2): 396–403. doi:10.2307/1378681. JSTOR 1378681.

- Soley, F.G. & Alvarado-Díaz, I. (8 July 2011). "Prospective thinking in a mustelid? Eira barbara (Carnivora) cache unripe fruits to consume them once ripened". Naturwissenschaften. 98 (8): 693–698. Bibcode:2011NW.....98..693S. doi:10.1007/s00114-011-0821-0. PMID 21739130.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Poglayen-Neuwall, I. "Copulatory behavior, gestation and parturition of the tayra." Bull. Br. Mus. (Nat. Hist.) Zool. 7 (1974): 1-140.

- Vaughan, R. (1974). "Breeding the tayra (Eira barbara) at Antelope Zoo, Lincoln". International Zoo Yearbook. 14: 120–122. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1090.1974.tb00791.x.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eira barbara. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Eira |

- Nowak, Ronald M. (2005). Walker's Carnivores of the World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. ISBN 0-8018-8032-7

- Emmons, L.H. (1997). Neotropical Rainforest Mammals, 2nd ed. University of Chicago Press ISBN 0-226-20721-8