Taranaki

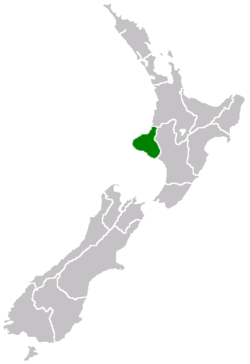

Taranaki is a region in the west of New Zealand's North Island. It is named after its main geographical feature, the stratovolcano of Mount Taranaki, also known as Mount Egmont.

Taranaki | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Country | New Zealand |

| Island | North Island |

| Seat | Stratford |

| Territorial authorities | List

|

| Government | |

| • Chairperson | David MacLeod |

| Area | |

| • Region | 7,257 km2 (2,802 sq mi) |

| Population (June 2019)[1] | |

| • Region | 122,700 |

| • Density | 17/km2 (44/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+12 (NZST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+13 (NZDT) |

| ISO 3166 code | NZ-TKI |

| HDI (2017) | 0.930[2] very high · 3rd |

| Website | www |

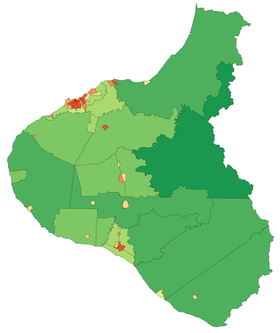

The main centre is the city of New Plymouth. The New Plymouth District is home to more than 65 per cent of the population of Taranaki.[3][4] New Plymouth is in North Taranaki along with Inglewood and Waitara. South Taranaki towns include Hāwera, Stratford, Eltham, and Opunake.

Since 2005, Taranaki has used the promotional brand "Like no other".[5]

Geography

Taranaki is on the west coast of the North Island, surrounding the volcanic peak of Mount Taranaki. The region covers an area of 7258 km². Its large bays north-west and south-west of Cape Egmont are North Taranaki Bight and South Taranaki Bight.

Mount Taranaki or Mount Egmont, the second highest mountain in the North Island, is the dominant geographical feature of the region. A Māori legend says that Taranaki previously lived with the Tongariro, Ngauruhoe and Ruapehu mountains of the central North Island but fled to its current location after a battle with Tongariro. A near-perfect cone, it last erupted in the mid-18th century. The mountain and its immediate surrounds form Egmont National Park.

Māori had called the mountain Taranaki for many centuries, and Captain James Cook gave it the English name of Egmont after the Earl of Egmont, the recently retired First Lord of the Admiralty who had encouraged his expedition. The mountain has two alternative official names, "Mount Taranaki" and "Mount Egmont".[6]

The region is exceptionally fertile thanks to generous rainfall and rich volcanic soil. Dairy farming predominates, with Fonterra's Whareroa milk factory just outside of Hāwera producing the largest volume of dairy ingredients from a single factory anywhere in the world.[7] There are also oil and gas deposits in the region, both on- and off-shore. The Maui gas field off the south-west coast has provided most of New Zealand's gas supply and once supported two methanol plants, (one formerly a synthetic-petrol plant called the Gas-To-Gasoline plant) at Motunui. Fuel and fertiliser is also produced at a well complex at Kapuni and a number of smaller land-based oilfields. With the Maui field nearing depletion, new offshore resources have been developed: the Kupe field, 30 km south of Hāwera and the Pohokura gas field, 4.5 km north of Waitara.[8]

The way the land mass projects into the Tasman Sea with northerly, westerly and southerly exposures, results in many excellent surfing and windsurfing locations, some of them considered world-class.

Demography

Taranaki has a population of 122,700 as of Statistics New Zealand's June 2019, 2.5 percent of New Zealand's population. It is the tenth most populous region of New Zealand.[1]

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1991 | 107,124 | — |

| 1996 | 106,590 | −0.10% |

| 2001 | 102,858 | −0.71% |

| 2006 | 104,127 | +0.25% |

| 2013 | 109,608 | +0.74% |

| 2018 | 117,561 | +1.41% |

| Source: [9][10] | ||

Taranaki Region had a population of 117,561 at the 2018 New Zealand census, an increase of 7,953 people (7.3%) since the 2013 census, and an increase of 13,434 people (12.9%) since the 2006 census. There were 45,249 households. There were 58,251 males and 59,310 females, giving a sex ratio of 0.98 males per female. Of the total population, 24,666 people (21.0%) were aged up to 15 years, 19,992 (17.0%) were 15 to 29, 52,464 (44.6%) were 30 to 64, and 20,436 (17.4%) were 65 or older. Figures may not add up to the total due to rounding.

Of those at least 15 years old, 13,776 (14.8%) people had a bachelor or higher degree, and 21,690 (23.3%) people had no formal qualifications. The median income was $29,900. The employment status of those at least 15 was that 44,673 (48.1%) people were employed full-time, 14,133 (15.2%) were part-time, and 3,681 (4.0%) were unemployed.[9]

Urban areas

Just under half the residents live in New Plymouth, with Hāwera being the next most populous town in the region.

| Urban area | Population (June 2019)[1] |

% of region |

|---|---|---|

| New Plymouth | 55,300 | 45.1% |

| Hāwera | 9,810 | 8.0% |

| Waitara | 7,040 | 5.7% |

| Stratford | 5,740 | 4.7% |

| Inglewood | 3,640 | 3.0% |

| Eltham | 1,970 | 1.6% |

| Opunake | 1,360 | 1.1% |

| Patea | 1,160 | 0.9% |

Culture and identity

| Largest groups of overseas-born residents[11] | |

| Nationality | Population (2013) |

|---|---|

| 5,328 | |

| 1,560 | |

| 939 | |

| 624 | |

| 579 | |

| 483 | |

| 480 | |

| 441 | |

| 351 | |

| 210 | |

The region has had a strong Māori presence for centuries. The local iwi (tribes) include Ngāti Mutunga, Ngāti Maru, Ngāti Ruanui, Taranaki, Te Āti Awa, Nga Rauru, Ngāruahinerangi and Ngāti Tama.

Ethnicities in the 2018 census were 84.8% European/Pākehā, 19.8% Māori, 2.1% Pacific peoples, 4.5% Asian, and 2.0% other ethnicities. People may identify with more than one ethnicity.

The percentage of people born overseas was 13.6, compared with 27.1% nationally.

Although some people objected to giving their religion, 51.7% had no religion, 36.0% were Christian, and 4.1% had other religions.[9]

History

The area became home to a number of Māori tribes from the 13th century. From about 1823 the Māori began having contact with European whalers as well as traders who arrived by schooner to buy flax.[12] In March 1828 Richard "Dicky" Barrett (1807–47) set up a trading post at Ngamotu (present-day New Plymouth).[13] Barrett and his companions, who were armed with muskets and cannon, were welcomed by the Āti Awa tribe for assisting in their continuing wars with Waikato Māori.[13] Following a bloody encounter at Ngamotu in 1832, most of the 2000 Āti Awa [13] living near Ngamotu, as well as Barrett, migrated south to the Kapiti region and Marlborough.

In late 1839 Barrett returned to Taranaki to act as a purchasing agent for the New Zealand Company, which had already begun on-selling the land to prospective settlers in England with the expectation of securing its title. Barrett claimed to have negotiated the purchase of an area extending from Mokau to Cape Egmont, and inland to the upper reaches of the Whanganui River including Mt Taranaki. A later deed of sale included New Plymouth and all the coastal lands of North Taranaki, including Waitara.

European settlement at New Plymouth began with the arrival of the William Bryan in March 1841. European expansion beyond New Plymouth, however, was prevented by Māori opposition to selling their land, a sentiment that deepened as links strengthened with the King Movement. Tension over land ownership continued to mount, leading to the outbreak of war at Waitara in March 1860. Although the pressure for the sale of the Waitara block resulted from the colonists' hunger for land in Taranaki, the greater issue fuelling the conflict was the Government's desire to impose British administration, law and civilisation on the Māori.[14]

The war was fought by more than 3,500 imperial troops brought in from Australia as well as volunteer soldiers and militia against Māori forces that fluctuated from a few hundred and to 1,500.[15] Total losses among the imperial, volunteer, and militia troops are estimated to have been 238, while Māori casualties totalled about 200.

An uneasy truce was negotiated a year later, only to be broken in April 1863 as tensions over land occupation boiled over again. A total of 5,000 troops fought in the Second Taranaki War against about 1,500 men, women and children. The style of warfare differed markedly from that of the 1860-61 conflict as the army systematically took possession of Māori land by driving off the inhabitants, adopting a "scorched earth" strategy of laying waste to the villages and cultivations of Māori, whether warlike or otherwise. As the troops advanced, the Government built an expanding line of redoubts, behind which settlers built homes and developed farms. The effect was a creeping confiscation of almost a million acres (4,000 km²) of land.[16]

The present main highway on the inland side of Mount Taranaki follows the path taken by the colonial forces under Major General Trevor Chute as they marched, with great difficulty, from Patea to New Plymouth in 1866.

Armed Māori resistance continued in South Taranaki until early 1869, led by the warrior Titokowaru, who reclaimed land almost as far south as Wanganui. A decade later, spiritual leader Te Whiti o Rongomai, based at Parihaka, launched a campaign of passive resistance against government land confiscation, which culminated in a raid by colonial troops on 5 November 1881.

The confiscations, subsequently acknowledged by the New Zealand Government as unjust and illegal,[17] began in 1865 and soon included the entire Taranaki district. Towns including Normanby, Hāwera and Carlyle (Patea) were established on land confiscated as military settlements.[18] The release of a Waitangi Tribunal report on the situation in 1996 led to some debate on the matter. In a speech to a group of psychologists, Associate Minister of Māori Affairs Tariana Turia compared the suppression of Taranaki Māori to the Holocaust, provoking a vigorous reaction[19] around New Zealand, with Prime Minister Helen Clark among those voicing criticism.

Economy

The subnational gross domestic product (GDP) of Manawatū-Whanganui was estimated at NZ$8.90 billion in the year to March 2019, 2.9% of New Zealand's national GDP. The regional GDP per capita was estimated at $73,029 in the same period, the second-highest in New Zealand (behind Wellington). In the year to March 2018, primary industries contributed $2.62 billion (30.0%) to the regional GDP, goods-producing industries contributed $2.13 billion (24.3%), service industries contributed $3.25 billion (37.1%), and taxes and duties contributed $750 million (8.6%).[20]

The main contributors to Taranaki's economy are dairy farming and hydrocarbon exploration.

Governance

Provincial government

From 1853 the Taranaki region was governed as the Taranaki Province (initially known as the New Plymouth Province) until the abolition of New Zealand provinces in 1876. The leading office was that of the superintendent.

The following is a list of superintendents of the Province of Taranaki during this time:

| Superintendent | Term |

|---|---|

| Charles Brown | 1853–1857 |

| George Cutfield | 1857–1861 |

| Charles Brown | 1861–1865 |

| Henry Robert Richmond | 1865–1869 |

| Frederic Carrington | 1869–1876 |

Taranaki Regional Council

The Taranaki Regional Council was formed as part of major nationwide local government reforms in November 1989, for the purpose of integrated catchment management. The regional council was the successor to the Taranaki Catchment Board, the Taranaki United Council, the Taranaki Harbours Board, and 16 small special-purpose local bodies that were abolished under the Local Government Amendment Act (No 3) 1988. The Council's headquarters were established in the central location of Stratford to "provide a good compromise in respect of overcoming traditional south vs north Taranaki community of interest conflicts" (Taranaki Regional Council, 2001 p. 6).

Chairmen

- Ross Allen (1989–2001)

- David Walter (2001–2007)

- David MacLeod (2007–present)

Motion picture location

Taranaki's landscape and the mountain's supposed resemblance to Mount Fuji led it to be selected as the location for The Last Samurai, a motion picture set in 19th-century Japan. The movie starred Tom Cruise.

Sports teams

Notable sports teams from Taranaki include:

- Port Taranaki Bulls - Mitre 10 Cup Rugby Union Team

- Team Taranaki - Central Premier League Football Team

- Taranaki Mountainairs - NBL Basketball Team

Notable people

- Sir Harry Atkinson – Premier of New Zealand and Colonial Treasurer

- Sir Peter Buck (Te Rangi Hīroa) of Ngāti Mutunga – Māori scholar, politician, military leader, health administrator, anthropologist, museum director, born in Urenui

- Sir Māui Wiremu Pita Naera Pōmare of Ngāti Mutunga - politician, Minister of Health

- Frederic Carrington – surveyor and father of New Plymouth

- William Douglas Cook – founder of Eastwoodhill Arboretum, Ngatapa, Gisborne and of Pukeiti, world-famous rhododendron garden, New Plymouth.

- Wiremu Kīngi – Māori Chief of Te Āti Awa, leader in the First Taranaki War

- William Malone – First World War officer

- Len Lye – artist, filmmaker born in Christchurch, collection only housed in New Plymouth

- Michael Smither – artist

- Ronald Syme – scholar of ancient history

- Te Whiti o Rongomai – spiritual leader of Parihaka and pioneer of peaceful protest strategies[21]

Sports people

- All Blacks: Beauden Barrett, Scott Barrett, Jordie Barrett, Grant Fox, Luke McAlister, Kayla McAlister, Graham Mourie, Conrad Smith, Carl Hayman

- Rugby League: Gavin Hill, Issac Luke, Curtis Rona, Howie Tamati

- Michael Campbell – golfer

- Paige Hareb – professional surfer

- Peter Snell – Gold medal winning athlete, born in Opunake

See also

- First Taranaki War

- Second Taranaki War

- Titokowaru's War

- New Zealand land confiscations

- Taranaki Rugby Football Union

- TSB Bank (New Zealand) – formerly Taranaki Savings Bank

- Water quality in Taranaki

References

- "Subnational Population Estimates: At 30 June 2019". Statistics New Zealand. 22 October 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- 2013 Census QuickStats about a place : Taranaki Region

- 2013 Census QuickStats about a place : New Plymouth District

- Harvey, Helen (5 October 2017). "'Taranaki Like No Other' trademark dispute resolved". Taranaki Daily News.

- "What is the difference between alternative naming and dual naming?". Archived from the original on 24 May 2010. Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- "Fonterra - Whareroa". www.fonterra.com. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- "Pohokura gas field". Todd Energy. Archived from the original on 26 May 2010.

- "Statistical area 1 dataset for 2018 Census". Statistics New Zealand. March 2020. Taranaki Region (07). 2018 Census place summary: Taranaki Region

- "2001 Census: Regional summary". archive.stats.govt.nz. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- "Birthplace (detailed), for the census usually resident population count, 2001, 2006, and 2013 (RC, TA) – NZ.Stat". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- Puke Ariki Museum essay Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Angela Caughey (1998). The Interpreter: The Biography of Richard "Dicky" Barrett. David Bateman Ltd. ISBN 1-86953-346-1.

- Belich, James (1986). The New Zealand Wars and the Victorian Interpretation of Racial Conflict (1st ed.). Auckland: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-011162-X.

- Michael King (2003). The Penguin History of New Zealand. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-301867-1.

- The Taranaki Report: Kaupapa Tuatahi by the Waitangi Tribunal, 1996 Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Ngati Awa Raupatu Report, chapter 10, Waitangi Tribunal, 1999.

- B. Wells, The History of Taranaki, 1878, Chapter 25.

- "A Taranaki Holocaust?" (2000) Downloadable Radio New Zealand broadcast Archived 10 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Regional gross domestic product: Year ended March 2019 | Stats NZ". www.stats.govt.nz. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- "'Te Whiti o Rongomai'". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

Further reading

- Tullett, J.S. (1981). The Industrious Heart: A History of New Plymouth. New Plymouth District Council.

- Belich, James (1988). The New Zealand Wars. Penguin.

- Scott, Dick (1998). Ask That Mountain. Reed. ISBN 0-7900-0190-X.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Taranaki. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Taranaki Region. |