Swimming

Swimming is the self-propulsion of a person through water, usually for recreation, sport, exercise, or survival. Locomotion is achieved through coordinated movement of the limbs, the body, or both. Humans can hold their breath underwater and undertake rudimentary locomotive swimming within weeks of birth, as a survival response.[1]

Swimming is consistently among the top public recreational activities,[2][3][4][5] and in some countries, swimming lessons are a compulsory part of the educational curriculum.[6] As a formalized sport, swimming features in a range of local, national, and international competitions, including every modern Summer Olympics.

Science

.jpg)

Swimming relies on the nearly neutral buoyancy of the human body. On average, the body has a relative density of 0.98 compared to water, which causes the body to float. However, buoyancy varies on the basis of body composition, lung inflation, and the salinity of the water. Higher levels of body fat and saltier water both lower the relative density of the body and increase its buoyancy. See also: Hydrostatic weighing

Since the human body is (slightly) less dense than water, water supports the weight of the body during swimming. As a result, swimming is “low-impact” compared to land activities such as running. The density and viscosity of water also create resistance for objects moving through the water. Swimming strokes use this resistance to create propulsion, but this same resistance also generates drag on the body.

Hydrodynamics is important to stroke technique for swimming faster, and swimmers who want to swim faster or exhaust less try to reduce the drag of the body's motion through the water. To be more hydrodynamic, swimmers can either increase the power of their strokes or reduce water resistance, though power must increase by a factor of three to achieve the same effect as reducing resistance.[7] Efficient swimming by reducing water resistance involves a horizontal water position, rolling the body to reduce the breadth of the body in the water, and extending the arms as far as possible to reduce wave resistance.[7]

Just before plunging into the pool, swimmers may perform exercises such as squatting. Squatting helps in enhancing a swimmer's start by warming up the thigh muscles.[8]

Infant swimming

Human babies demonstrate an innate swimming or diving reflex from newborn until the age of approximately 6 months.[9] Other mammals also demonstrate this phenomenon (see mammalian diving reflex). The diving response involves apnea, reflex bradycardia, and peripheral vasoconstriction; in other words, babies immersed in water spontaneously hold their breath, slow their heart rate, and reduce blood circulation to the extremities (fingers and toes).[9] Because infants are innately able to swim, classes for babies of about 6 months old are offered in many locations. This helps build muscle memory and makes strong swimmers from a young age.

Technique

Swimming can be undertaken using a wide range of styles, known as 'strokes,' and these strokes are used for different purposes, or to distinguish between classes in competitive swimming. It is not necessary to use a defined stroke for propulsion through the water, and untrained swimmers may use a 'doggy paddle' of arm and leg movements, similar to the way four-legged animals swim.

There are four main strokes used in competition and recreation swimming: the front crawl, also known as freestyle, breaststroke, backstroke and butterfly. Competitive swimming in Europe started around 1800, mostly using the breaststroke. In 1873, John Arthur Trudgen introduced the trudgen to Western swimming competitions.[10] Butterfly was developed in the 1930s, and was considered a variant of the breaststroke until accepted as a separate style in 1953.[11] Butterfly is considered the hardest stroke by many people, but it is the most effective for all-around toning and the building of muscles.[12] It also burns the most calories and can be the second fastest stroke if practiced regularly.[12]

Other strokes exist for specific purposes, such as training or rescue, and it is also possible to adapt strokes to avoid using parts of the body, either to isolate certain body parts, such as swimming with arms only or legs only to train them harder, or for use by amputees or those affected by paralysis.

History

Swimming has been recorded since prehistoric times, and the earliest records of swimming date back to Stone Age paintings from around 7,000 years ago. Written references date from 2000 BC. Some of the earliest references include the Epic of Gilgamesh, the Iliad, the Odyssey, the Bible (Ezekiel 47:5, Acts 27:42, Isaiah 25:11), Beowulf, and other sagas.

The coastal tribes living in the volatile Low Countries were known as excellent swimmers by the Romans. Men and horses of the Batavi tribe could cross the Rhine without losing formation, according to Tacitus. Dio Cassius describes one surprise tactic employed by Aulus Plautius against the Celts at the Battle of the Medway:[13]

The [British Celts] thought that Romans would not be able to cross it without a bridge, and consequently bivouacked in rather careless fashion on the opposite bank; but he sent across a detachment of [Batavii], who were accustomed to swim easily in full armour across the most turbulent streams. . . . Thence the Britons retired to the river Thames at a point near where it empties into the ocean and at flood-tide forms a lake. This they easily crossed because they knew where the firm ground and the easy passages in this region were to be found, but the Romans in attempting to follow them were not so successful. However, the [Batavii] swam across again and some others got over by a bridge a little way up-stream, after which they assailed the barbarians from several sides at once and cut down many of them."

In 1538, Nikolaus Wynmann, a Swiss–German professor of languages, wrote the earliest known complete book about swimming, Colymbetes, sive de arte natandi dialogus et festivus et iucundus lectu (The Swimmer, or A Dialogue on the Art of Swimming and Joyful and Pleasant to Read).[14]

Purpose

There are many reasons why people swim, from swimming as a recreational pursuit to swimming as a necessary part of a job or other activity. Swimming may also be used to rehabilitate injuries, especially various cardiovascular and muscle injuries. People may also pursue swimming as a career or field of interest. Some may be gifted and choose to compete professionally and go onto claim fame.

Recreation

Many swimmers swim for recreation, with swimming consistently ranking as one of the physical activities people are most likely to take part in. Recreational swimming can also be used for exercise, relaxation or rehabilitation.[15] The support of the water, and the reduction in impact, make swimming accessible for people who are unable to undertake activities such as running. Swimming is one of the most relaxing activities, water is known to calm us and can help reduce stress.

Health

Swimming is primarily a cardiovascular/aerobic exercise[16] due to the long exercise time, requiring a constant oxygen supply to the muscles, except for short sprints where the muscles work anaerobically. Furthermore, swimming can help tone and strengthen muscles.[17] Swimming allows sufferers of arthritis to exercise affected joints without worsening their symptoms. However, swimmers with arthritis may wish to avoid swimming breaststroke, as improper technique can exacerbate arthritic knee pain.[18] As with most aerobic exercise, swimming reduces the harmful effects of stress. Swimming is also effective in improving health for people with cardiovascular problems and chronic illnesses. It is proven to positively impact the mental health of pregnant women and mothers. Swimming can even improve mood.[19]

Disabled swimmers

As of 2020, the Americans with Disabilities Act requires that swimming pools in the United States be accessible to disabled swimmers.[20]

Elderly swimmers

"Water-based exercise can benefit older adults by improving quality of life and decreasing disability. It also improves or maintains the bone health of post-menopausal women."[21] Swimming is an ideal workout for the elderly, mainly because it presents little risk of injury and is also low impact. Exercise in the water works out all muscle groups, helping with conditions such as muscular dystrophy which is common in seniors.

Sport

Swimming as a sport predominantly involves participants competing to be the fastest over a given distance in a certain period of time. Competitors swim different distances in different levels of competition. For example, swimming has been an Olympic sport since 1896, and the current program includes events from 50 m to 1500 m in length, across all four main strokes and medley. During the season competitive swimmers typically train several times a week, this is in order to preserve fitness as well as promoting overload in training. Furthermore when the cycle of work is completed swimmers go through a stage called taper where intensity is reduce in preparation for racing, during taper power and feel in the water are concentrated.

The sport is governed internationally by the Fédération Internationale de Natation (FINA), and competition pools for FINA events are 25 or 50 meters in length. In the United States, a pool 25 yards in length is commonly used for competition.

Other swimming and water-related sporting disciplines include open water swimming, diving, synchronized swimming, water polo, triathlon, and the modern pentathlon.

Safety

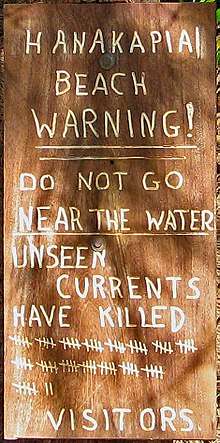

As a popular leisure activity done all over the world, one of the primary risks of swimming is drowning. Drowning may occur from a variety of factors, from swimming fatigue to simply inexperience in the water. From 2005 to 2014, an average of 3,536 fatal unintentional drownings occurred in the United States, approximating 10 deaths a day.[22]

To minimize the risk and prevent potential drownings from occurring, lifeguards are often employed to supervise swimming locations such as pools and beaches. Different lifeguards receive different training depending on the sites that they are employed at; i.e. a waterfront lifeguard receives more rigorous training than a poolside lifeguard. Well-known aquatic training services include the National Lifesaving Society and the Canadian Red Cross, which specialize in training lifeguards in North America.

Occupation

Some occupations require workers to swim, such as abalone and pearl diving, and spearfishing.

Swimming is used to rescue people in the water who are in distress, including exhausted swimmers, non-swimmers who have accidentally entered the water, and others who have come to harm on the water. Lifeguards or volunteer lifesavers are deployed at many pools and beaches worldwide to fulfill this purpose, and they, as well as rescue swimmers, may use specific swimming styles for rescue purposes.

Swimming is also used in marine biology to observe plants and animals in their natural habitat. Other sciences use swimming; for example, Konrad Lorenz swam with geese as part of his studies of animal behavior.

Swimming also has military purposes. Military swimming is usually done by special operation forces, such as Navy SEALs and US Army Special Forces. Swimming is used to approach a location, gather intelligence, engage in sabotage or combat, and subsequently depart. This may also include airborne insertion into water or exiting a submarine while it is submerged. Due to regular exposure to large bodies of water, all recruits in the United States Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard are required to complete basic swimming or water survival training.

Swimming is also a professional sport. Companies sponsor swimmers who have the skills to compete at the international level. Many swimmers compete competitively to represent their home countries in the Olympics. Professional swimmers may also earn a living as entertainers, performing in water ballets.

Risks

There are many risks associated with voluntary or involuntary human presence in water, which may result in death directly or through drowning asphyxiation. Swimming is both the goal of much voluntary presence and the prime means of regaining land in accidental situations.

Most recorded water deaths fall into these categories:

- Panic occurs when an inexperienced swimmer or a nonswimmer becomes mentally overwhelmed by the circumstances of their immersion, leading to sinking and drowning. Occasionally, panic kills through hyperventilation, even in shallow water.

- Exhaustion can make a person unable to sustain efforts to swim or tread water, often leading to death through drowning. An adult with fully developed and extended lungs has generally positive or at least neutral buoyancy, and can float with modest effort when calm and in still water. A small child has negative buoyancy and must make a sustained effort to avoid sinking rapidly.

- Hypothermia, in which a person loses critical core temperature, can lead to unconsciousness or heart failure.

- Dehydration from prolonged exposure to hypertonic salt water—or, less frequently, salt water aspiration syndrome where inhaled salt water creates foam in the lungs that restricts breathing—can cause loss of physical control or kill directly without actual drowning. Hypothermia and dehydration also kill directly, without causing drowning, even when the person wears a life vest.

- Blunt trauma in a fast moving flood or river water can kill a swimmer outright, or lead to their drowning.

Adverse effects of swimming can include:

- Exostosis, an abnormal bony overgrowth narrowing the ear canal due to frequent, long-term splashing or filling of cold water into the ear canal, also known as surfer's ear

- Infection from water-borne bacteria, viruses, or parasites

- Chlorine inhalation (in swimming pools)

- Heart attacks while swimming (the primary cause of sudden death among triathlon participants, occurring at the rate of 1 to 2 per 100,000 participations.[25])

- Adverse encounters with aquatic life:

- Stings from sea lice, jellyfish, fish, seashells, and some species of coral

- Puncture wounds caused by crabs, lobsters, sea urchins, zebra mussels, stingrays, flying fish, sea birds, and debris

- Hemorrhaging bites from fish, marine mammals, and marine reptiles, occasionally resulting from predation

- Venomous bites from sea snakes and certain species of octopus

- Electrocution or mild shock from electric eels and electric rays

Around any pool area, safety equipment is often important,[26] and is a zoning requirement for most residential pools in the United States.[27] Supervision by personnel trained in rescue techniques is required at most competitive swimming meets and public pools.

Lessons

Traditionally, children were considered not able to swim independently until 4 years of age,[28] although now infant swimming lessons are recommended to prevent drowning.[29]

In Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Estonia and Finland, the curriculum for the fifth grade (fourth grade in Estonia) states that all children should learn how to swim as well as how to handle emergencies near water. Most commonly, children are expected to be able to swim 200 metres (660 ft)—of which at least 50 metres (160 ft) on their back – after first falling into deep water and getting their head under water. Even though about 95 percent of Swedish school children know how to swim, drowning remains the third most common cause of death among children.

In both the Netherlands and Belgium swimming lessons under school time (schoolzwemmen, school swimming) are supported by the government. Most schools provide swimming lessons. There is a long tradition of swimming lessons in the Netherlands and Belgium, the Dutch translation for the breaststroke swimming style is even schoolslag (schoolstroke). In France, swimming is a compulsory part of the curriculum for primary schools. Children usually spend one semester per year learning swimming during CP/CE1/CE2/CM1 (1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th grade).

In many places, swimming lessons are provided by local swimming pools, both those run by the local authority and by private leisure companies. Many schools also include swimming lessons into their Physical Education curricula, provided either in the schools' own pool or in the nearest public pool.

In the UK, the "Top-ups scheme" calls for school children who cannot swim by the age of 11 to receive intensive daily lessons. Children who have not reached Great Britain's National Curriculum standard of swimming 25 meters by the time they leave primary school receive a half-hour lesson every day for two weeks during term-time.[30]

In Canada and Mexico there has been a call to include swimming in public school curriculum.[31]

In the United States there is the Infant Swimming Resource (ISR)[32] initiative that provides lessons for infant children, to cope with an emergency where they have fallen into the water. They are taught how to roll-back-to-float (hold their breath underwater, to roll onto their back, to float unassisted, rest and breathe until help arrives).

In Switzerland, swimming lessons for babies are popular, to help them getting used to be in another element. At the competition level, unlike in other countries - such as the Commonwealth countries, swimming teams are not related to educational institutions (high-schools and universities), but rather to cities or regions.

Clothing and equipment

Swimsuits

Standard everyday clothing is usually impractical for swimming and is unsafe under some circumstances. Most cultures today expect swimmers to wear swimsuits.

Men's swimsuits commonly resemble shorts, or briefs. Casual men's swimsuits (for example, boardshorts) are rarely skintight, unlike competitive swimwear, like jammers or diveskins. In most cases, boys and men swim with their upper body exposed, except in countries where custom or law prohibits it in a public setting, or for practical reasons such as sun protection.

Modern women's swimsuits are generally skintight, covering the pubic region and the breasts (See bikini). Women's swimwear may also cover the midriff as well. Women's swimwear is often a fashion statement, and whether it is modest or not is a subject of debate by many groups, religious and secular.

Competitive swimwear is built so that the wearer can swim faster and more efficiently. Modern competitive swimwear is skintight and lightweight. There are many kinds of competitive swimwear for each gender. It is used in aquatic competitions, such as water polo, swim racing, diving, and rowing.

Wetsuits provide both thermal insulation and flotation. Many swimmers lack buoyancy in the leg. The wetsuit reduces density and therefore improves buoyancy while swimming. It provides insulation by absorbing some of the surrounding water, which then heats up when in direct contact with skin. The wetsuit is the usual choice for those who swim in cold water for long periods of time, as it reduces susceptibility to hypothermia.

Some people also choose to wear no clothing while swimming; this is known as skinny dipping. In some European countries public pools have naturist sessions to allow clothes-free swimming and many countries have naturist beaches where one can swim naked. It is legal to swim naked in the sea at all UK beaches. It was common for males to swim naked in a public setting up to the early 20th century. Today, skinny dipping can be a rebellious activity or merely a casual one.

Accessories

- Ear plugs can prevent water from getting in the ears.

- Noseclips can prevent water from getting in the nose. However, this is generally only used for synchronized swimming. Using nose clips in competitive swimming can cause a disadvantage, so many competitive swimmer choose not to use one. It is for this reason that nose clips are primarily used for synchronized swimming and recreational swimming.

- Goggles protect the eyes from chlorinated water, and improve underwater visibility. Tinted goggles protect the eyes from sunlight that reflects from the bottom of the pool.

- Swim caps keep the body streamlined and protect the hair from chlorinated water, though they are not entirely watertight.

- Kickboards are used to keep the upper body afloat while exercising the lower body.

- Pull buoys are used to keep the lower body afloat while exercising the upper body.

- Swimfins are used to elongate the kick and improve technique and speed. Fins also build upper calf muscles.

- Hand paddles are used to increase resistance during arm movements, with the goal of improving technique and power.

- Finger paddles have a similar effect to handle paddles however due to their smaller size create less resistance. They also help with improving a swimmers 'catch' in the water.

- Snorkels are used to help improve and maintain a good head position in the water. They may also be used by some during physical therapy.

- Pool noodles are used to keep the user afloat during the time in the water.

- Safety fencing and equipment is mandatory at public pools and a zoning requirement at most residential pools in the United States.[33]

- Swimming Parachutes are used in competitive training, adding an element of resistance in the water helping athletes to increase power in the strokes central movements.

- Inflatable armbands are swimming aids designed to provide buoyancy for the swimmer which helps the wearer to float.

See also

References

- McGraw, Myrtle B (1939). "Swimming behavior of the human infant". The Journal of Pediatrics. 15 (4): 485–490. doi:10.1016/s0022-3476(39)80003-8.

- Pereira da Costa, Lamartine; Miragaya, Ana (2002). Worldwide Experiences and Trends in Sport for All. Meyer & Meyer Verlag. ISBN 9781841260853.

- Jones, Helen; Millward, Peter; Buraimo, Babtunde (August 2011). Adult participation in sport (PDF). Department for Culture, Media and Sport. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-06-10.

- "Swimming remains England's most popular sport despite free scheme setback". The Daily Telegraph. London. 2010-06-18.

- "America's Swim Team" (PDF). USA Swimming.

- "Swimming Lessons in Educational Curriculum Across the World". Aquamobile. 2015-04-04.

- Laughlin, Terry (1996). Total Immersion. Fireside, New York.

- Swimming Anatomy, Publisher: Human Kinetics, Year: 2010, ISBN 9781450409179, page: 147

- Goksor, E.; Rosengren, L.; Wennergren, G. (2002). "Bradycardic response during submersion in infant swimming". Acta Paediatrica. 91 (3): 307–312. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2002.tb01720.x. PMID 12022304.

- "History of Swimming | Ramona Aquatics". ramonaaquatics.net. Retrieved 2017-02-25.

- Taormina, Sheila (2014-10-01). Swim Speed Strokes for Swimmers and Triathletes: Master Freestyle, Butterfly, Breaststroke and Backstroke for Your Fastest Swimming. VeloPress. ISBN 9781937716608.

- "Best swimming stroke for weight loss | Benefits of the strokes". Just Swim. 2016-11-14. Retrieved 2018-09-18.

- "Cassius Dio — Book 60".

- Escalante, Yolanda; Saavedra, Jose M. (30 May 2012). "Swimming and Aquatic Activities: State of the Art". Journal of Human Kinetics. 32: 5–7. doi:10.2478/v10078-012-0018-4. ISSN 1640-5544. PMC 3590867. PMID 23487594.

- Katz, Jane (2003). Your Water Workout (First ed.). Broadway Books. ISBN 978-0-7679-1482-6.

- Cooper, Kenneth H. (1983) [1968]. Aerobics (revised, reissue ed.). Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0553274479.

- Services, Department of Health & Human. "Swimming - health benefits". Retrieved 2018-09-11.

- "How to Fix and Prevent Breaststroker's Knee". YourSwimLog.com. 2016-09-03. Retrieved 2019-11-16.

- "CDC - Health Benefits of Water-based Exercise - Healthy Swimming & Recreational Water - Healthy Water". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2015-10-01.

- Ahlers, Mike M.; Dunnan, Tory. "Americans with Disabilities Act opens pools to disabled swimmers". cnn.com. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- "Health Benefits of Water-based Exercise". CDC.gov. United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- https://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/water-safety/waterinjuries-factsheet.html

- "Top athlete escaped the GDR using his aquatic talents". Dw-world.de.

- "Chronology of Albanian Immigration to Italy". Ccat.sas.upenn.edu.

- Kevin M. Harris, MD; et al. (2010). "Sudden Death During the Triathlon". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Overview of safety recommendations at swimming pools". Swimmingpool.com. Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- "Division of Code Enforcement and Administration". Dos.ny.gov. 2006-12-14. Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- Injury Prevention Committee (2003). "Swimming lessons for infants and toddlers". Paediatrics & Child Health. 8 (2): 113–114. doi:10.1093/pch/8.2.113. PMC 2791436. PMID 20019931. Archived from the original on 2006-07-12.

- "Drowning Happens Quickly– Learn How to Reduce Your Risk". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 20 August 2014. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- Davies, Catriona (2006-06-14). "Children unable to swim at 11 are given top-up lessons". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 2006-07-12.

- "Federal minister calls for school swim lessons". CTV. 2005-07-18. Archived from the original on 2009-04-12. Retrieved 2006-06-28.

- "Infant Swimming Resource site". Infantswim.com. Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- "Pool safety equipment overview". Swimmingpool.com. Retrieved 2014-04-13.

Bibliography

- Cox, Lynne (2005). Swimming to Antarctica: Tales of a Long-Distance Swimmer. Harvest Books. ISBN 978-0-15-603130-1.

- Maniscalco F., Il nuoto nel mondo greco romano, Naples 1993.

- Mehl H., Antike Schwimmkunst, Munchen 1927.

- Schuster G., Smits W. & Ullal J., Thinkers of the Jungle. Tandem Verlag 2008.

- Sprawson, Charles (2000). Haunts of the Black Masseur - The Swimmer as Hero. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-3539-9.svin

- Tarpinian, Steve (1996). The Essential Swimmer. The Lyons Press. ISBN 978-1-55821-386-9.

External links

| Look up swimming in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Swimmingstrokes.info, Overview of 150 historical and less known swimming-strokes