Log driving

Log driving is a means of moving logs (sawn tree trunks) from a forest to sawmills and pulp mills downstream using the current of a river. It was the main transportation method of the early logging industry in Europe and North America.[1]

History

When the first sawmills were established, they were usually small water powered facilities located near the source of timber, which might be converted to grist mills after farming became established when the forests had been cleared. Later, bigger circular sawmills were developed in the lower reaches of a river, with the logs floated down to them by log drivers.[2] In the broader, slower stretches of a river, the logs might be bound together into timber rafts.[3] In the smaller, wilder stretches of a river, rafts couldn't get through, so masses of individual logs were driven down the river like huge herds of cattle. "Log floating" in Sweden (timmerflottning) had begun by the 16th century, and 17th century in Finland (tukinuitto).[4] The total length of timber-floating routes in Finland was 40,000km.[4]

The log drive was one step in a larger process of lumber-making in remote places. In a location with snowy winters, the yearly process typically began in autumn when a small team of men hauled tools upstream into the timbered area, chopped out a clearing, and constructed crude buildings for a logging camp.[5] In the winter when things froze, a larger crew moved into the camp and proceeded to cut trees, cutting the trunks into 5-metre (16 ft) lengths, and hauling the logs with oxen or horses over iced trails to the riverbank. There the logs were decked onto "rollways." In spring when snow thawed and water levels rose, the logs were rolled into the river, and the drive commenced.[6]

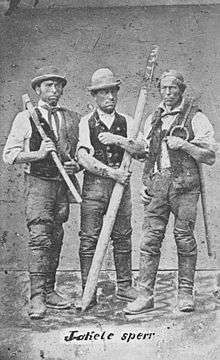

To ensure that logs drifted freely along the river, men called "log drivers" or "river pigs" were needed to guide the logs. The drivers typically divided into two groups. The more experienced and nimble men comprised the "jam" crew or "beat" crew. They watched the spots where logs were likely to jam, and when a jam started, tried to get to it quickly and dislodge the key logs before many logs stacked up. If they didn't, the river would keep piling on more logs, forming a partial dam which could raise the water level.[7] Millions of board feet of lumber could back up for miles upriver, requiring weeks to break up, with some timber lost if it was shoved far enough into the shallows.[8] When the jam crew saw a jam begin, they rushed to it and tried to break it up, using peaveys and possibly dynamite. This job required some understanding of physics, strong muscles, and extreme agility. The jam crew was an exceedingly dangerous occupation, with the drivers standing on the moving logs and running from one to another. Many drivers lost their lives by falling and being crushed by the logs.[7]

Each crew was accompanied by an experienced boss often selected for his fighting skills to control the strong and reckless men of his team. The overall drive was controlled by the "walking boss" who moved from place to place to coordinate the various teams to keep logs moving past problem spots. Stalling a drive near a saloon often created a cascade of drunken personnel problems.[9]

A larger group of less experienced men brought up the rear, pushing along the straggler logs that were stuck on the banks and in trees. They spent more time wading in icy water than balancing on moving logs. They were called the "rear crew." Other men worked with them from the bank, pushing logs away with pike poles. Others worked with horses and oxen to pull in the logs that had strayed furthest out into the flats.[7]

Bateaux ferried log drivers using pike poles to dislodge stranded logs while maneuvering with the log drive.[10] A wannigan was a kitchen built on a raft which followed the drivers down the river.[7] The wannigan served four meals a day[11] to fuel the men working in cold water. It also provided tents and blankets for the night if no better accommodations were available.[7] A commissary wagon carrying clothing, plug tobacco and patent medicines for purchase by the log drivers was also called a wangan. The logging company wangan train, called a Mary Anne, was a caravan of wagons pulled by four- or six-horse teams where roads followed the river to transport the tents, blankets, food, stoves, and tools needed by the log drivers.[12]

For log drives, the ideal river would have been straight and uniform, with sharp banks and a predictable flow of water. Wild rivers were not that, so men cut away the fallen trees that would snag logs, dynamited troublesome rocks, and built up the banks in places. To control the flow of water, they built "flash dams" or "driving dams" on smaller streams, so they could release water to push the logs down when they wanted.[13]

Each timber firm had its own mark which was placed on the logs, called an "end mark". Obliterating or altering a timber mark was a crime.[14] At the mill the logs were captured by a log boom, and the logs were sorted for ownership before being sawn.[7]

Log drives were often in conflict with navigation, as logs would sometimes fill the entire river and make boat travel dangerous or impossible.[15]

Floating logs down a river worked well for the most desirable pine timber, because it floated well. But hardwoods were more dense, and weren't buoyant enough to be easily driven, and some pines weren't near drivable streams. Log driving became increasingly unnecessary with the development of railroads and the use of trucks on logging roads. However, the practice survived in some remote locations where such infrastructure did not exist. Most log driving in the US and Canada ended with changes in environmental legislation in the 1970s. Some places, like the Catalan Pyrenees, still retain the practice as a popular holiday celebration once a year.

In Sweden legal exemptions for log driving were eliminated in 1983. "The last float in southern Sweden was in the 1960s, with the floating era in the rest of the country ending completely with the last log drive in the Klarälven river in 1991."[4]

Popular culture

- The figure of speech "High and Dry" describes an unsuccessful log drive. Maximum river flows typically coincided with the runoff from snowmelt, and was sometimes augmented by water released from flash dams. If logs were started downriver when there was not enough water to move them all the way to the sawmill, the investment made in cutting that timber might be stranded high and dry in shallows along the stream for a year until the next spring snowmelt.[16]

- The phrase "Come Hell or High Water", used when one is determined to get something accomplished no matter how hard or whatever difficulties one may face, originated in the race to get logs into the brooks and streams so that they could reach the rivers while the water was high enough to float the drive.[17]

- The contemporary logrolling contest, Birling, is a demonstration of skills originally devised by log drivers.[10]

- Inclusive description of a complex assortment as "the whole Mary Anne" derives from the colorful characters of wangan caravans which periodically transformed quiet rural communities with the excitement of a passing log drive.

- In Canada, "The Log Driver's Waltz" is a popular folk song which boast about a log driver's dancing skills.

- The version of the Canadian one-dollar bank note issued in 1974 and withdrawn in 1989 featured a view of the Ottawa River with log driving taking place in the foreground and Parliament Hill rising in the background. This banknote was part of the fourth series of banknotes released by the Bank of Canada entitled "Scenes of Canada". The logs depicted in this bank note may have been destined for a half dozen pulp, paper and sawmills near the Chaudière Falls immediately upstream from Parliament Hill, or for other mills further downstream.

- An Englishman may have observed loggers loitering in Bangor, Maine when he reported in 1801: "His habits in the forest and the [river] voyage all break up the system of persevering industry and substitute one of alternate toil and indolence, hardship and debauch; and in the alteration, indolence and debauch will inevitably be indulged in the greatest possible proportion."[18]

- In the first chapter of The Cider House Rules (1985), John Irving briefly describes a 1930s log drive.

- Harry Brandelius’ 1950s Swedish song Flottarkärlek tells the story of a young log driver.[4]

- Teuvo Pakkala’s 1899 Finnish play Tukkijoella started the so-called ‘log driver romantics’ phase, resulting in several movies and books about log drivers’ lives.[4]

- The song Breakfast in Hell by Slaid Cleaves tells the tale of the death of Sandy Grey, a driver in Ontario.[19]

- In the first four chapters of John Irving's novel Last Night in Twisted River (2009), the hard and dangerous life of log drivers in New Hampshire is described in detail.

Sources

- Holbrook, Stewart H. (1961). Yankee Loggers. International Paper Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Notes

- "Manistee National Forest (N.F.), Pere Marquette Wild and Scenic River (WSR), Proposed, Environmental Impact Statement". Manistee National Forest. December 31, 1976. p. 62. Retrieved September 29, 2019.

- Holbrook 1961, pp. 42-43.

- Rosholt, Malcolm (1980). The Wisconsin Logging Book - 1839-1939 (PDF). Rosholt, Wisconsin: Rosholt House. p. 190. ISBN 0-910417-05-9.

- Kari, Serafia (September 2019). "Taming the rivers: log driving in Sweden and Finland". Europeana (CC By-SA). Retrieved 2019-09-28.

- Rosholt, Malcolm (1982). Lumbermen on the Chippewa - The Camp (PDF). Rosholt, Wisconsin: Rosholt House. p. 8. ISBN 0-910417-00-8.

- Rosholt, Malcolm (1982). Lumbermen on the Chippewa (PDF). Rosholt, Wisconsin: Rosholt House. p. 23. ISBN 0-910417-00-8.

- Rosholt, Malcolm (1982). Lumbermen on the Chippewa - The Drive (PDF). Rosholt, Wisconsin: Rosholt House. pp. 63–64. ISBN 0-910417-00-8.

- Rosholt, Malcolm (1980). The Wisconsin Logging Book - 1839-1939 (PDF). Rosholt, Wisconsin: Rosholt House. p. 182. ISBN 0-910417-05-9.

- Holbrook 1961, pp. 53-56,64,66,72.

- Holbrook 1961, p. 119.

- "Log Drives (and River Pigs)". Forest History Center. Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved 2012-04-07.

- Holbrook 1961, p. 65.

- Vogel, John N. (1982–1983). "The Round Lake logging dam: a survivor of Wisconsin's log-driving days". Wisconsin Magazine of History. 66 (3): 176. Retrieved 2011-09-22.

- Rosholt, Malcolm (1982). Lumbermen on the Chippewa - End Marks and Bark Marks (PDF). Rosholt, Wisconsin: Rosholt House. pp. 91–95. ISBN 0-910417-00-8.

- Wheeler, Scott (September 2002). The History of Logging in Vermont's Northeast Kingdom. The Kingdom Historical.

- Holbrook 1961, p. 66.

- Bob Howells. Back Roads of New England, Gulf Publishing Company, 1995.

- Holbrook 1961, p. 18.

- "Baring, "Breakfast in Hell" - Maine Folklife Center - University of Maine". Maine Folklife Center. Retrieved 2019-12-01.

External links

- "Thrills Of The Spring Log Drive", February 1931, Popular Mechanics large article on a log drive in Quebec, Canada

- "The Wisconsin Logging Book 1839-1939" by Malcolm Rosholt is readable, has many old photos, and is available online.

- "Lumbermen on the Chippewa", also by Rosholt, has more of the same.