Paper marbling

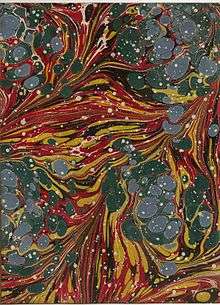

Paper marbling is a method of aqueous surface design, which can produce patterns similar to smooth marble or other kinds of stone. The patterns are the result of color floated on either plain water or a viscous solution known as size, and then carefully transferred to an absorbent surface, such as paper or fabric. Through several centuries, people have applied marbled materials to a variety of surfaces. It is often employed as a writing surface for calligraphy, and especially book covers and endpapers in bookbinding and stationery. Part of its appeal is that each print is a unique monotype.

Procedure

There are several methods for making marbled papers. A shallow tray is filled with water, and various kinds of ink or paint colors are carefully applied to the surface with an ink brush. Various additives or surfactant chemicals are used to help float the colors. A drop of "negative" color made of plain water with the addition of surfactant is used to drive the drop of color into a ring. The process is repeated until the surface of the water is covered with concentric rings. The floating colors are then carefully manipulated either by blowing on them directly or through a straw, fanning the colors, or carefully using a human hair to stir the colors. In the 19th century, the Kyoto-based Japanese suminagashi master Tokutaro Yagi developed an alternative method that employed a split piece of bamboo to gently stir the colors, resulting in concentric spiral designs. A sheet of washi paper is then carefully laid onto the water surface to capture the floating design. The paper, which is often made of kozo (paper mulberry), must be unsized and strong enough to withstand being immersed in water without tearing.

Another method of marbling more familiar to Europeans and Americans is made on the surface of a viscous mucilage, known as size or sizing in English. While this method is often referred to as "Turkish marbling" in English and called ebru in modern Turkish, ethnic Turkic peoples were not the only practitioners of the art, as Persian, Tajiks, and people of Indian origin also made these papers. The use of the term Turkish by Europeans is most likely due to both the fact that many first encountered the art in Istanbul, as well as essentialist references to all Muslims as Turks, much as Europeans were referred to as Firengi in Turkish and Persian, which literally means Frankish.

Historic forms of marbling used both organic and inorganic pigments mixed with water for colors, and sizes were traditionally made from gum tragacanth (Astragalus spp.), gum karaya, guar gum, fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum), fleabane, linseed, and psyllium. Since the late 19th century, a boiled extract of the carrageenan-rich alga known as Irish moss (Chondrus crispus), has been employed for sizing. Today, many marblers use powdered carrageenan extracted from various seaweeds. Another plant-derived mucilage is made from sodium alginate. In recent years, a synthetic size made from hydroxypropyl methylcellulose, a common ingredient in instant wallpaper paste, is often used as a size for floating acrylic and oil paints.

In the size-based method, colors made from pigments are mixed with a surfactant such as ox gall. Sometimes, oil or turpentine may be added to a color, to achieve special effects. The colors are then spattered or dropped onto the size, one color after another until there is a dense pattern of several colors. Straw from the broom corn was used to make a kind of whisk for sprinkling the paint, or horsehair to create a kind of drop-brush. Each successive layer of pigment spreads slightly less than the last, and the colors may require additional surfactant to float and uniformly expand. Once the colors are laid down, various tools and implements such as rakes, combs, and styluses are often used in a series of movements to create more intricate designs.

Paper or cloth is often mordanted beforehand with aluminium sulfate (alum) and gently laid onto the floating colors (although methods such as Turkish ebru and Japanese suminagashi do not require mordanting). The colors are thereby transferred and adhered to the surface of the paper or material. The paper or material is then carefully lifted off the size and hung up to dry. Some marblers gently drag the paper over a rod to draw off the excess size. If necessary, excess bleeding colors and sizing can be rinsed off, and then the paper or fabric is allowed to dry. After the print is made, any color residues remaining on the size are carefully skimmed off of the surface, in order to clear it before starting a new pattern.

Contemporary marblers employ a variety of modern materials, some in place of or in combination with the more traditional ones. A wide variety of colors are used today in place of the historic pigment colors. Plastic broom straw can be used instead of broom corn, as well as bamboo sticks, plastic pipettes, and eye droppers to drop the colors on the surface of the size. Ox gall is still commonly used as a surfactant for watercolors and gouache, but synthetic surfactants are used in conjunction with acrylic, PVA, and oil-based paints.

History in East Asia

An intriguing reference which some think may be a form of marbling is found in a compilation completed in 986 CE entitled 文房四谱 (Wen Fang Si Pu) or "Four Treasures of the Scholar's Study" edited by the 10th century scholar-official 蘇易簡 Su Yijian (957–995 CE). This compilation contains information on inkstick, inkstone, ink brush, and paper in China, which are collectively called the four treasures of the study. The text mentions a kind of decorative paper called 流沙箋 Liu Sha Jian meaning “drifting-sand” or “flowing-sand notepaper" that was made in what is now the region of Sichuan (Su 4: 7a–8a).

This paper was made by dragging a piece of paper through a fermented flour paste mixed with various colors, creating a free and irregular design. A second type was made with a paste prepared from honey locust pods, mixed with croton oil, and thinned with water. Presumably, both black and colored inks were employed. Ginger, possibly in the form of an oil or extract, was used to disperse the colors, or “scatter” them, according to the interpretation given by T.H. Tsien. The colors were said to gather together when a hair-brush was beaten over the design, as dandruff particles was applied to the design by beating a hairbrush over top. The finished designs, which were thought to resemble human figures, clouds, or flying birds, were then transferred to the surface of a sheet of paper. An example of paper decorated with floating ink has never been found in China. Whether or not the above methods employed floating colors remains to be determined (Tsien 94–5).

Su Yijian was an Imperial scholar-official and served as the chief of the Hanlin Academy from about 985–993 CE. He compiled the work from a wide variety of earlier sources and was familiar with the subject, given his profession. Yet it is important to note that it is uncertain how personally acquainted he was with the various methods for making decorative papers that he compiled. He most likely reported information given to him, without having a full understanding of the methods used. His original sources may have predated him by several centuries. Not only is it necessary to identify the original source to attribute a firm date for the information, but also the account remains uncorroborated due to a lack of any surviving physical evidence of marbling in Chinese manuscripts.

In contrast, Suminagashi (墨流し), which means "floating ink" in Japanese, appears to be the earliest form of marbling during the 12th-century Sanjuurokuninshuu (三十六人集), located in Nishihonganji (西本願寺), Kyoto.[2] Author Einen Miura states that the oldest reference to suminagashi papers are in the waka poems of Shigeharu, (825–880 CE), a son of the famed Heian era poet Narihira (Muira 14) in the Kokin Wakashū, but the verse has not been identified and even if found, it may be spurious. Various claims have been made regarding the origins of suminagashi. Some think that may have derived from an early form of ink divination (encromancy). Another theory is that the process may have derived from a form of popular entertainment at the time, in which a freshly painted Sumi painting was immersed into water, and the ink slowly dispersed from the paper and rose to the surface, forming curious designs, but no physical evidence supporting these allegations has ever been identified.

According to legend, Jizemon Hiroba is credited as the inventor of suminagashi. It is said that he felt divinely inspired to make suminagashi paper after he offered spiritual devotions at the Kasuga Shrine in Nara Prefecture. He then wandered the country looking for the best water with which to make his papers. He arrived in Echizen, Fukui Prefecture where he found the water especially conducive to making suminagashi. So he settled there, and his family carried on with the tradition to this day. The Hiroba Family claims to have made this form of marbled paper since 1151 CE for 55 generations (Narita, 14).

History in the Islamic World

The method of floating colors on the surface of mucilaginous sizing is thought to have emerged in the regions of Greater Iran and Central Asia by the late 15th century. It may have first appeared during the end of the Timurid Dynasty, whose final capital was in the city of Herat, located in Afghanistan today. Other sources suggest it emerged during the subsequent Shaybanid dynasty, in the cities of Samarqand or Bukhara, in what is now modern Uzbekistan. Whether or not this method was somehow related to earlier Chinese or Japanese methods mentioned above has never been concretely proven.

The Persianate method, known as kāghaẕ-e abrī (كاغذ ابرى), in Persian or often by the simplified form of abrī (ابرى), is attested in several historical accounts.[4] Annemarie Schimmel translated this term as "clouded paper" in English. While Sami Frashëri claimed in his Kamus-ı Türki, that the term was "more properly derived from the Chagatai word ebre" (ابره); he provided no example of usage to support this assertion. In contrast, most historical Persian, Turkish, and Urdu texts refer to the paper as abrī alone. Today in Turkey, the art is commonly known as ebru, a cognate of the term abri first documented in the 19th century. In modern Iran, it is often called abr-o-bâd (ابرو باد), meaning "cloud and wind".[5]

The art first emerged and evolved during the long 16th century in the Safavid Persia and Ottoman Turkey, as well as Mughal and the Deccan Sultanates in India. Within these regions, various methods emerged in which colors were made to float on the surface of a bath of viscous liquid mucilage or size, made from various plants. These include katheera or kitre- gum tragacanth (Astragalus often used as a binder by apothecaries in making tablets), shambalîleh or methi- fenugreek seed (an ingredient in curry mixtures), and sahlab or salep (the roots of "Orchis mascula", which is commonly used to make a popular beverage).

A pair of leaves bearing rudimentary drop-motifs are considered among the earliest examples of this paper, held in the Kronos Collection. One of the sheets bears an accession notation on the reverse stating "These abris are rare" (یاد داشت این ابریهای نادره است) and adds that it was "among the gifts from Iran" to the royal library of Ghiyath Shah, the ruler of the Malwa Sultanate, dated Hijri year 1 Dhu al-Hijjah 901/11 August 1496 of the Common Era.[6]

Approximately a century later, a variant approach using different tools and including rakes, combs, and other apparatus were used to manipulate both finely prepared mineral and organic pigments, resulting in more elaborate, intricate, and mesmerizing designs. In India, the abri technique was combined with 'aks, masking with resist or stencils, to create a unique and very rare form of miniature painting, attributed to the Deccan plateau region of India and especially the city of Bijapur in particular, during the Adil Shahi dynasty in the 17th century. The topic of marbling in India is understudied and conclusive determinations have yet to be made, especially in light of discoveries made in the last 20 years.

The earliest examples of Ottoman marbled paper may be the margins attached to a cut paper découpage manuscript of the Hâlnâma (حالنامه) by the poet Arifi (popularly known as the Gû-yi Çevgân [Ball and Polo-stick]) completed by Mehmed bin Gazanfer in 1539–40. One early master by the name of Shebek is mentioned posthumously in the earliest Ottoman text on the art known as the Tertîb-i Risâle-yi Ebrî (ترتیبِ رسالۀ ابری, an Arrangement of a Treatise on Ebrî), which based on internal evidence dates to after 1615. Several recipes described in the text are attributed to this master. Another famous 18th-century master by the name of Hatip Mehmed Efendi (died 1773) is accredited with developing motif and perhaps early floral designs, although evidence from Iran and India contradicts some of these claims. Despite this, marbled motifs are commonly referred to as "Hatip" designs today in Turkey.

The current Turkish tradition of ebru dates to the mid-19th century, with a series of masters associated with a branch of the Naqshbandi Sufi order based at what is known as the Özbekler Tekkesi (Lodge of the Uzbeks), located in Sultantepe, near Üsküdar.[7] The founder of this line is accredited to Sadık Effendi (died 1846). While the claim that Sadık Efendi first learned the art in Bukhara and brought it to Istanbul is uncorroborated, he taught it to his sons Edhem and Salıh. Based upon this later practice, many Turkish marblers assert that the art was perpetuated by Sufis for centuries, although clear evidence to support this claim has never been established. "Hezarfen" Edhem Effendi (died 1904) is attributed with developing the art as a kind of cottage industry for the tekke, to supply Istanbul's burgeoning printing industry with the decorative paper. It is said that the papers were tied into bundles and sold by weight. Many of these papers were of the neftli design, made with turpentine, analogous to what is called stormont in English.

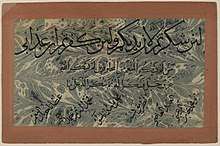

The premier student of Edhem Efendi was Necmeddin Okyay (1885–1976). He was the first to teach the art at the Fine Arts Academy in Istanbul. He is famous for the development of floral styles of marbling, in addition to yazılı ebru a method of writing traditional calligraphy using a gum-resist method in conjunction with ebru. Okyay's premier student was Mustafa Düzgünman (1920–1990), the teacher of many contemporary marblers in Turkey today. He is known for codifying the traditional repertoire of patterns, to which he only added a floral daisy design, in the manner of his teacher.[8]

History in Europe

The oldest paper marbling business in Venice and most of the western world is Legatorial Piazzesi, dating back to the 15th century. [9]

In the 17th century European travelers to the Middle East collected examples of these papers and bound them into alba amicorum, which literally means "books of friendship" in Latin, and is a forerunner of the modern autograph album. Eventually the technique for making the papers reached Europe, where they became a popular covering material not only for book covers and end-papers, but also for lining chests, drawers, and bookshelves. The marbling of the edges of books was also a European adaptation of the art.

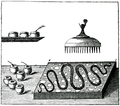

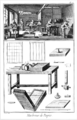

The methods of marbling attracted the curiosity of early scientists during the Renaissance. The earliest published account in Europe was written in Dutch by Gerhard ter Brugghen in his Verlichtery kunst-boeck in Amsterdam in 1616, while the first German account was written by Daniel Schwenter, published posthumously in his Delicæ Physico-Mathematicæ in 1671 (Wolfe, 16). Athanasius Kircher published a Latin account in Ars Magna Lucis et Umbræ in Rome in 1646, which was widely disseminated throughout Europe. A thorough overview of the art with illustrations of marblers at work, and images of the tools of the trade was published in the Encyclopédie of Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert.[10][11][12]

The art became a popular handicraft in the 19th century after the English maker Charles Woolnough published his The Art of Marbling (1853). In it, he describes how he adapted a method of marbling onto book-cloth, which he exhibited at the Crystal Palace Exhibition in 1851. (Wolfe, 79) Further developments in the art were made by Josef Halfer, a bookbinder of German origin, who lived in Budakeszi, in Hungary.[13] Halfer discovered a method for preserving carrageenan, and his methods superseded earlier ones in Europe and the US.

Marbling tray and tools from School of Arts (1750)

Marbling tray and tools from School of Arts (1750) Marblers at work, from l'Encyclopedie of Diderot and d'Alembert

Marblers at work, from l'Encyclopedie of Diderot and d'Alembert An edge marbler and paper finisher with related equipment, from l'Encyclopedie

An edge marbler and paper finisher with related equipment, from l'Encyclopedie

In the 21st century

Marbled paper is still made today, and the method is now applied to fabric and three-dimensional surfaces, as well as paper. Aside from continued traditional applications, artists now explore using the method as a kind of painting technique, and as an element in collage. In the last two decades, marbling has been the subject of international symposia and museum exhibitions. The first International Marblers' Gathering was held in Santa Fe NM in 1989 sponsored by the marbling journal Ink & Gall. Active international groups can be found on social media networks such as Facebook and also the International Marbling Network.

Marbling has been adapted for temporary decoration of hands and faces for events such as festivals. Neon or ultraviolet reactive colours are typically used, and the paint is water-based and non-toxic.[14][15]

Examples

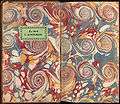

Marbled endpaper from a book bound in the Netherlands or Germany between 1720 and 1770

Marbled endpaper from a book bound in the Netherlands or Germany between 1720 and 1770 Marbled endpaper from a book bound in France around 1735

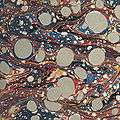

Marbled endpaper from a book bound in France around 1735 Paper marbling from a book bound in England around 1830

Paper marbling from a book bound in England around 1830 Paper marbling from a book bound in England around 1830 (detail)

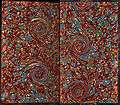

Paper marbling from a book bound in England around 1830 (detail) Marbled endpaper from a book bound in France around 1880

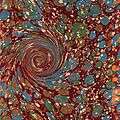

Marbled endpaper from a book bound in France around 1880 Marbled endpaper from a book bound in France around 1880 (detail)

Marbled endpaper from a book bound in France around 1880 (detail).jpg) A combed marbled pattern from the front flyleaf of a binding of The Playmate: A Pleasant Companion for Spare Hours by Joseph Cundall, Printed by Barclay, 1847.

A combed marbled pattern from the front flyleaf of a binding of The Playmate: A Pleasant Companion for Spare Hours by Joseph Cundall, Printed by Barclay, 1847. Combed marbled paper, from the front flyleaf of a binding of Oriental Fragments by Maria Hack, printed in London for Harvey and Dartman, 1828.

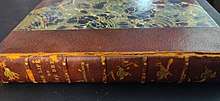

Combed marbled paper, from the front flyleaf of a binding of Oriental Fragments by Maria Hack, printed in London for Harvey and Dartman, 1828. 1912 edition of Dodd, Mead and Company's The Life of the Bee by Maurice Maeterlinck

1912 edition of Dodd, Mead and Company's The Life of the Bee by Maurice Maeterlinck Frontispiece detail of The Life of the Bee

Frontispiece detail of The Life of the Bee

See also

Notes

- "?".

- "suminagashi 墨流し". Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- "Qur'anic verse (14:7) on blue and white marble paper". Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- "ابری.» دائرة المعارف بزرگ اسلامی»". Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- "Parsiblog". Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- Haidar, Navina Najat; Sardar, Marika (13 April 2015). Sultans of Deccan India, 1500–1700: Opulence and Fantasy». ISBN 9780300211108. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- "Art of Ebrû". Archived from the original on 29 November 2007. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- "Ebru Masters". Archived from the original on 29 November 2007. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/travel/things-to-do/shopping-in-venice-unique-venetian-souvenirs-what-to-buy-and-where/marble-paper/ps56932688.cms

- Denis Diderot. Jean le Rond d'Alembert; Robert Morrissey (eds.). "Marbreur de papier". Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, etc., eds. Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond D'Alembert. University of Chicago: ARTFL Encyclopédie Project. Archived from the original on 13 July 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- Diderot, Denis. "Marbreur de papier". Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, etc., eds. Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond D'Alembert. University of Chicago: ARTFL Encyclopédie Project. Archived from the original on 1 July 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- Diderot, Denis. "Marbled paper, (Arts.; English Text)". Encyclopédie... The Encyclopédie of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. hdl:2027/spo.did2222.0001.236.

- "Die Vergangenheit von Budakeszi". Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- Valenti, Lauren (9 September 2016). "The New "Body Marbling" Trend Is Must-See Stuff, People". Marie Claire.

- Scott, Ellen (9 September 2016). "Body Marbling Is the New Festival Trend You're Going to Be Obsessed with". Metro.

References

- Chambers, Ann (1991). Suminagashi: The Japanese Art of Marbling. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-486-24651-5.

- Grunebaum, Gabriele (2003). How to Marbleize Paper. Dover. ISBN 0-486-24651-5.

- Miura, Einen (1991). The Art of Marbled Paper: Marbled Patterns and How to Make Them. Kodansha International. ISBN 4-7700-1548-8.

- Narita, Kiyofusa (1954). Japanese Paper-making. Hokuseido Press.

- Porter, Yves (1994). Painters, Paintings, and Books: An Essay on Indo-Persian Technical Literature, 12–19th Centuries. Manohar: Centre for Human Sciences. ISBN 81-85425-95-7.

- Tsien, Tsuen-hsuin (1985). Paper and Printing. Science and Civilization v. 5. Chemistry and chemical technology: pt. 1. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-521-08690-6.

- Wolfe, Richard J. (1990). Marbled Paper: Its History, Techniques, and Patterns: With Special Reference to the Relationship of Marbling to Bookbinding in Europe and the Western World. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-8188-8.

- Su, Yijian (2008). Wen Fang Si Pu. Shi dai wen yi chu ban she. ISBN 978-7-5387-2380-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paper marbling. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to |

- Digital collection of the Washington University Libraries with many high-resolution images of paper marbling

- The International Marbling Network

- Article about marbled paper by Joel Silver from Fine Books magazine, Nov./Dec. 2005 issue

- About suminagashi and other marbling techniques

- A collection of information on Ebru

- Ebru (compilation of articles) by Cetin Koc.