St Mary's Church, Watford

St Mary's Watford is a Church of England church in Watford, Hertfordshire, in the United Kingdom. It is situated in the town centre on Watford High Street, approximately 25 kilometres (16 mi) outside London. St Mary's is the parish church of Watford and is part of the Anglican Diocese of St Albans. Thought to be at least 800 years old, the church contains burials of a number of local nobility and some noteworthy monumental sculpture of the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras.

| St Mary's Watford | |

|---|---|

View of St Mary's from the East | |

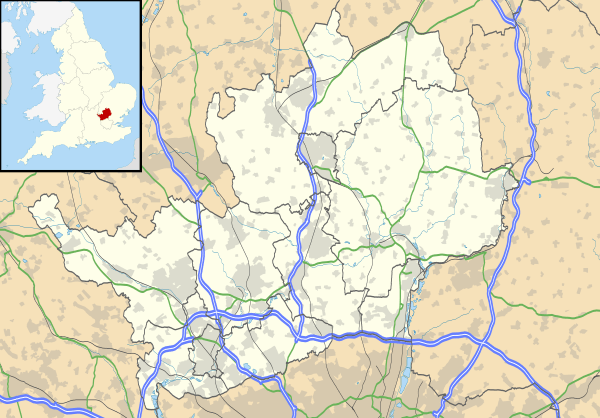

St Mary's Watford Location of St Mary's | |

| 51.654563°N 0.395923°W | |

| OS grid reference | TQ1196 |

| Location | Church Street, Watford WD18 0EG |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Churchmanship | Evangelical |

| Website | stmaryswatford.org |

| History | |

| Founded | 1100 or later |

| Events | 1871 renovated |

| Architecture | |

| Heritage designation | Grade I listed |

| Style | Early English Gothic |

| Specifications | |

| Spire height | 33 metres (108 ft) (including 'spike') |

| Bells | 10 (1704, 1919 & 1946) |

| Tenor bell weight | 1,237 kilograms (2,727 lb) |

| Administration | |

| Parish | Watford |

| Diocese | Diocese of St Albans |

| Province | Province of Canterbury |

| Clergy | |

| Vicar(s) | Rev. Tony Rindl |

History

No documentary records exist of the origins of Watford Parish Church; the earliest parish records do not begin until 1539,[1] but the church is understood to be considerably older. The building seen today is mainly 15th century in origin, although the oldest parts of the fabric are estimated to date from around 1230. During renovations in 1871, church restorers discovered that 12th-century stonework had been incorporated into the later medieval building, and in the hardcore of the tower walls, the basin of a 12th-century baptismal font had been discarded. The presence of masonry from this era suggests that St Mary's Church was probably established at around the same time that the charter was granted for Watford Market to the Lord of the Manor at Cashio, an Abbott of St Albans Abbey. The precise date that this licence was awarded is not known; historians estimate that it was during the reign of either King Henry I (1100-1135) or King Henry II (1154–1189).[2][3]

Among the past vicars of St Mary's was William Capel, son of William Capell, 3rd Earl of Essex and noted amateur cricketer.

On 18 July 1909, King Edward VII attended a service of worship during a visit to the Earl of Clarendon at the Grove. He entered the church through the door to the Essex Chapel, which is now known as the Edward VII door.[4]

The patron of the church was the Earl of Essex.[5]

Architecture & Memorials

Constructed in stone and faced in flint, the church has a broad clock tower at the west end typical for Hertfordshire, topped with crenelations. The six-bay nave is flanked by north and south aisles lined with octagonal piers, above which runs a clerestory. The nave is topped by a timber roof with the beams resting on carved angels. Seen from the outside, St Mary's is for the most part a 15th-century building; the tower, outer walls of the aisles, clerstory, nave roof and south chancel chapel all date from this period. The chancel forms the older part of the church, the chancel arch and double piscina having been dated as 13th century.[6][7]

Sometime in the late 13th century, a chapel was added to the south aisle. Dedicated to St Katherine, this chapel was built by John Heydon (d.1400) of The Grove Estate in Watford, and was hence known as the Heydon Chapel. By the time the church was being recorded by the historian John Edwin Cussans in his History of Hertfordshire (1880), the Heydon Chapel was in use as an organ chamber. Carved into one of the pillars which separate the chapel from the chancel was a coat of arms which Robert Clutterbuck identified as the family arms of the Heydons.[1]

The pulpit dates from 1714, the work of by Richard Bull. The church contains a number of marble monuments to local townspeople, dating from the 17th and 18th centuries. Of particular note is a white marble tablet in the Choristers' Vestry to the memory of Robert Clutterbuck, the author of a History of Hertfordshire. In a vault beneath are also interred many of the Clutterbuck family.

Restoration works

The church interior was restored in 1848, and the church underwent a major restoration in 1871, led by the architect John Thomas Christopher; plans were also considered at this time for alterations to the church by the architect Sir George Gilbert Scott.[8] During Christopher's refurbishment works the exterior plaster was removed and refaced with knapped flint, battlements were added to the tower, the south aisle walls were rebuilt, new roofs were built, and alterations were made to the 15th-century south chapel. Interior fittings introduced at this time included an ornate stone font carved by James Forsyth and a stone reredos carved by E Renversey. Stained glass by the glassmakers firm Heaton, Butler and Bayne was installed.[7] The oak box pews installed at this time were especially noted as a fine example of carved ornamentation in the Decorated Gothic style with tracery heads and foliate spandrels.[9]

A further restoration project was undertaken in 1987, including repairs to the roof and organ.[6][8] In 1979 a new octagonal church hall was constructed on the south side of the church.[10]

21st-century refurbishment

A refurbishment scheme for the church interior was announced in 2014, which involved laying new flooring, installing internal plate glass screens, and the removal of George Gilbert Scott's oak pews to replace them with modern upholstered chairs.[11] The controversial scheme was approved by the Church of England consistory court but was opposed by conservationists; heritage bodies such as the Victorian Society and Historic England, along with Watford Borough Council, objected to the plans.[12]

The refurbishment work was carried out from late 2017 to March 2019. The box pews were taken out and the decorated end panels were reused for interior panelling. During removal of the old floor, 13 hidden burial vaults were uncovered which had to be documented and conserved prior to installation of the underfloor heating and new stone floor.[13]

Nave

Among the memorials which survived the Victorian restoration is a large monumental brass to Hugh de Holes (d.1415) and his wife; de Holes is depicted wearing the judicial robes of a judge. A white marble tablet, on the south wall of the nave, is dedicated to the memory of Jane Bell, wife of John Bell, Esq. Its unusually long epitaph was written by Dr. Samuel Johnson. There are many other minor monuments, including a marble memorial to Anne Derne (d.1790), daughter of John Carpender, by J. Golde of High Holborn.[7]

The organ was installed in 1935 and is the work of organ builders J. W. Walker & Sons Ltd.[10]

St Mary's is now a Grade I listed building.[8]

The Essex Chapel

St Mary's Watford was the parish church to the nearby Cassiobury Estate and served as a burial place for the nobility of Watford. The north chancel chapel is known as the Essex Chapel, or the Morison Chapel, containing the burials of the Earls of Essex, along with the tombs of Morison and Capel families. This chapel was founded in 1595 by Bridget, Dowager Countess of Bedford and widow of Sir Richard Morison, and Francis Russell, 2nd Earl of Bedford and is noted for its outstanding monuments. Two table tombs originally stood in the middle of the chapel, one for Countess Bridget (who died in 1600) and one for Lady Dame Elizabeth Russell (died 1611), the wife of William Lord Russell; these tombs were removed in 1907 to the Bedford family chapel in the Church of St Michael, Chenies, Buckinghamshire. In 1916 the chapel was restored by Adele, Dowager Countess of Essex, in memory of her husband, George Capell, 7th Earl of Essex.[14][15]

The most striking memorials in the chapel are two large wall monuments executed by the sculptor Nicholas Stone, described by Pevsner as "the chief glory of Watford Church".[7] On one side is the tomb of the politician Sir Charles Morison (1549-1599), son of Dowager Countess Bridget, which features a reclining effigy of Sir Charles in white marble, depicted with a Van Dyke beard and wearing armour and a large Elizabethan ruff round his neck. Morrison is surrounded by an ornate canopy of twin segmental arches supported by two pillars of coloured marble, the family coat of arms, and at either end figures of his son and daughter kneel under sculpted fabric baldacchinos. A long Latin inscription describes his numerous virtues and states that he was the founder of the chapel.[7][16][17]

Opposite this is the tomb of his son, Sir Charles Morrison, 1st Baronet, who died in 1628, designed in a similar style with semi-reclining figures of Sir Charles and his wife Mary sculpted in marble. Sir Charles is depicted wearing armour, resting on his elbow, with a skull under his hand, raised above the recumbent figure of his wife; she represented reclining on a cushion, wearing a richly embroidered dress of the period and ruff. The figures are enclosed in a four-poster canopy and below them at either end are the kneeling figures of a youth, a boy and a young lady kneeling. The Latin inscription at the bottom describe how their daughter, Elizabeth, married Arthur Capell, 1st Baron Capell of Hadham (in 1627).[7][16][17]

Among the other memorials in the chapel is a mural monument to George Capell-Coningsby, 5th Earl of Essex (1757–1839), which bears a finely sculpted coat of arms;[18] a memorial to Harriet, daughter of the 5th Earl, who died in 1837, aged 29; a simple marble memorial to Arthur Algernon Capell, 6th Earl of Essex (1803-1892); a memorial to his son, Arthur de Vere Capell, Viscount Malden (1826–1879); a memorial to Caroline Janetta, wife of the 6th Earl and daughter of the Duke of St. Albans (died 1862); and a brass tablet to Randolph, second son of Janetta and the 6th Earl of Essex, who served in the naval brigade in the Crimean War at the Battle of Inkerman and the Siege of Sebastopol, and died at Rio de Janeiro, in 1857, aged 25, "much lamented, soon after he had reached that place."[16] Also buried here is Lady Mary Capell (1722–1782), the daughter of William Capell, 3rd Earl of Essex and wife of the Royal Navy officer John Forbes.

A smaller wall monument depicting a female figure kneeling between two marble pillars has been identified as that of Lady Dorothy Morrison (d.1618), wife of Sir Charles Morrison the elder.[7][16][17]

The Churchyard

A number of heritage-listed 18th and 19th-century neoclassical chest tombs can be found in St Mary's churchyard. They contain the burials of several notable Watford townsfolk who were influential in the development of the town as an industrial centre. Among these tombs is that of a ship's captain of the East India Company, James Dundas; the tomb of John Dyson, who founded the Watford brewery which was later to become Benskins Brewery; the tomb of Elizabeth and Ralph Morrison, who died in 1772 and 1780 respectively (no known relation to the Morrisons of Cassiobury House); the Clutterbuck Tomb, marking the burials of the Clutterbuck family, a large Hertfordshire family whose descendants included Robert Clutterbuck, the noted historian who wrote the 1815 county history The History and Antiquities of the County of Hertford; and the grave of George Edward Doney (d. 1809), a freed slave from Virginia who had originally been taken from the Gambia as an infant and who, after emancipation, had been employed as a domestic servant at Cassiobury House by the 5th Earl of Essex.[19][20]

An unusual legend surrounds a grave known as the Fig Tree Tomb; the unknown person buried here was said to have been a convinced atheist who, according to the story, had stated on their deathbed that if there is a God, a fig tree should grow out of their heart. After their death in the early 1800s, a fig tree did indeed grow out of this tomb for many years, breaking through the stone until it was killed by the severe winter of 1962/63.[21]

Location

St Mary's lies on Watford High Street, opposite the Watford Intu shopping Centre and approximately 0.2 miles (320 m) from Watford High Street railway station.

References

- McGhan (1981). Genealogies of Virginia families : from Tyler's quarterly historical and genealogical magazine. Baltimore: Genealogical Pub. Co. p. 177. ISBN 9780806309477. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- Slater & Goose, p.281

- Slater & Goose, p.278

- Cooper - "The King Enters St Mary's Church"

- Commissioners appointed to consider the state of the established Church (1835). Liber ecclesiasticus. An authentic statement of the revenues of the Established Church, compiled from the report of the Commissioners. p. 211. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- Historic England. "Church of St Mary (1101120)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- Pevesner, p.385

- "Nationally Listed Buildings in Watford". Watford Borough Council. p. 17.

- Tracy, Charles (31 August 2015). "St Mary's Church, Watford, Hertfordshire - The nave and chancel timber furniture: A significance assessment" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 May 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- "St Mary's Watford History and Bells" (PDF). St Mary's Watford. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- Blok, Frans (30 June 2014). "Refurbishing St. Mary's Church - 3Develop beeldblog / image blog". 3Develop. Archived from the original on 19 May 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- Lennon, Matthew. "Controversial church facelift plans given green light despite objections from conservation groups". Watford Observer. Archived from the original on 26 July 2017. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- "St Mary's Church Watford". Premier Construction News. 15 November 2019. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- Rabbitts, Paul; Priestley, Sarah (2014). Cassiobury: The Ancient Seat of the Earls. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 9781445638805. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- Slater & Goose, p.284

- "Watford in 1880". Hertfordshire Genealogy. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- Hall, S.C.; Jewitt, Llewellyn (1871). "Cassiobury". The Art Journal. London: Virtue. 10: 256. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- "Watford (St Mary)". A Topographical Dictionary of England, Volume 4. London: Samuel Lewis. 1835. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- "Guide to St Mary's Tombs" (PDF). Watford Museum. Watford Borough Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 December 2014. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- "The Tombs". Watford Junction. Watford Museum. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- Cooper - "The Fig Tree Tomb"

Bibliography

- Slater, Terry; Goose, Nigel (2008). A county of small towns : the development of Hertfordshire's urban landscape to 1800. Hatfield: Univ. of Hertfordshire Press. p. 281. ISBN 9781905313440. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; revised by Cherry, Bridget (2002). "Watford - Churches". The Buildings of England: Hertfordshire (2nd ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 385. ISBN 9780300096118. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- Cooper, John (2013). Watford Through Time. Amberley. ISBN 9781445632032. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

External links

![]()