Rye House, Hertfordshire

Rye House near Hoddesdon in Hertfordshire is a former fortified manor house, located in what is now the Lee Valley Regional Park. The gatehouse is the only surviving part of the structure and is a Grade I listed building.[2] The house gave its name to the Rye House Plot, an assassination attempt of 1683 that was a violent consequence of the Exclusion Crisis in British politics at the end of the 1670s.

| Rye House, Hertfordshire | |

|---|---|

The gatehouse of Rye House (2009)[1], the only surviving part of the manor house | |

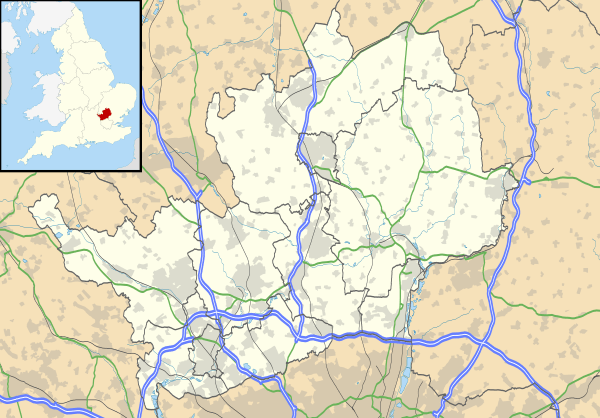

Location in Hertfordshire | |

| General information | |

| Location | Lee Valley Park |

| Coordinates | 51.7711°N 0.007°E |

| Construction started | c.1443 |

History

The ownership of Rye House was very stable over four centuries; but the fabric gradually ran down, and the buildings diminished.

Foundation

Andres Pedersen, a Danish soldier who took part in the Hundred Years' War, was denizenised in England in 1433, becoming Sir Andrew Ogard.[3] In 1443 he was allowed to impark part of the manor of Rye, the area then called the Isle of Rye, in the parish of Stanstead Abbots, and was given licence to crenellate what became Rye House.[4] Over 50 types of moulded brick were used in its construction.[5]

Early Modern period

In 1517 William Parr was living at Rye House;[6] it was the main family home for the Parrs, Catherine Parr and Anne Parr also, after their father's death, until 1531.[7][8] It passed in 1577 to Joyce Frankland from her husband William.[9] The Frankland family sold it to the Baeshe family, in 1619.[4]

It was later the setting of the Rye House Plot. In 1683, when the putative plot was actively being discussed, it was occupied by Richard Rumbold, one of the conspirators.[10] It was bought by the Fieldes family in 1676,[11] in the person of the Hertford MP Edmund Feilde (or Field).[12]

From the 19th century

By 1834 Rye House had become a workhouse. Subsequently (William) Henry Teale developed it into a tourist attraction,[13] buying the House and 50 acres in 1864.[4] There were a maze and a bowling green, among other features.[14] An affray there in 1885 between Catholic excursionists and Orangemen led to a question in the House of Commons.[15] In 1911 it was described as a hotel. For many years the Great Bed of Ware was on display.[16]

The moat was put to uses including growing water cress.[14][17] The part that had been filled in was excavated in the 1980s.[11]

Geography

The local geography played a significant part in the history of the House. At Hoddesdon the River Stort runs into the River Lea, and the area was often flooded. The lord of the manor of Rye maintained a bridge over the Lea, and a causeway. The causeway became part of the coaching road via Bishop's Stortford into East Anglia.[4]

Engraving from 1777, showing the gatehouse brickwork before restoration. By 1795 some of this brickwork had gone.[12]

Engraving from 1777, showing the gatehouse brickwork before restoration. By 1795 some of this brickwork had gone.[12] View from the road (1777 engraving), facing south-west

View from the road (1777 engraving), facing south-west Rye House, 1823 engraving. The long building was a barn and malting-house, then used as a workhouse

Rye House, 1823 engraving. The long building was a barn and malting-house, then used as a workhouse Poster from around 1880, advertising excursions to Rye House from London terminuses

Poster from around 1880, advertising excursions to Rye House from London terminuses Engraving by Edmund Hort New from an 1897 edition of The Compleat Angler

Engraving by Edmund Hort New from an 1897 edition of The Compleat Angler

References

- Elevation by T. P. Smith.

- British Listed Buildings, Rye House Gatehouse, Stanstead Abbots.

- Dorothy J. Clayton, The Administration of the County Palatine of Chester, 1442–1485 (1990), p. 64; Google Books.

- "William Henry Page, 'Parishes: Stanstead Abbots', A History of the County of Hertford: volume 3 (1912), pp. 366–373". Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- Anthony Emery, Discovering Medieval Houses (2008), p. 78; Google Books.

- James, Susan E. "Parr, William". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21405. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Janel Mueller, Katherine Parr: Complete Works and Correspondence (2011), p. 5; Google Books.

- Porter, Linda (2010). Katherine the Queen: The remarkable life of Katherine Parr. Macmillan. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-230-71039-9.

- Wright, Stephen. "Frankland, Joyce". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/10084. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Clifton, Robin. "Rumbold, Richard". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/24269. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Anthony Emery, Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300–1500: East Anglia, Central England, and Wales (2000), pp. 289–91; Google Books.

- R. T. Andrews, The Rye House and its Plot, p. 146, in Percy Cross Standing (editor), Memorials of Old Hertfordshire (1905);archive.org.

- Pastscape, Rye House. Archived 5 September 2012 at Archive.today

- Edward Walford, Greater London: a narrative of its history, its people and its places, vol. 1 (1894), p. 563;archive.org.

- Hansard HC Deb 20 July 1885 vol 299 cc1194-5.

- Karl Baedeker (Firm), London and its Environs; handbook for travellers (1911), p. 417; archive.org.

- "Oh! It really is a wery pretty garden/And Rye'ouse from the cock-loft could be seen/where the chickweed man undresses/to bathe 'mong the water cresses/If it wasn't for the 'ouses in between.." Music Hall song of the late 19th century, sung by Gus Elen