Klaus Störtebeker

"Nikolaus" Storzenbecher or "Klaus" Störtebeker (1360 – supposed 20 October 1401) was reputed to be leader of a group of privateers known as the Victual Brothers (German: Vitalienbrüder). The Victual Brothers (Latin: victualia) were originally hired during a war between Denmark and Sweden to fight the Danish and supply the besieged Swedish capital Stockholm with provisions. After the end of the war, the Victual Brothers continued to capture merchant vessels for their own account and named themselves "Likedeelers" (literally: equal sharers).[1] Recent studies manifest that Störtebeker was not called "Klaus" by prename but "Johann".[2]

Störtebeker | |

|---|---|

Reconstruction of head from skull ascribed to Störtebeker | |

| Born | 1360 Wismar, Hanseatic League (present-day Germany) |

| Died | assumed 20 October 1401 (aged 40–41) assumed Hamburg, present-day Germany |

| Cause of death | execution by beheading |

| Other names | Storzenbecher |

| Occupation | merchant, privateer, violent entrepreneur |

| Years active | assumed 1392–1401 |

Biography

A large number of myths and legends surround the few facts known about Störtebeker's life. His name is both a nickname and a surname, meaning "empty the mug with one gulp" in Low Saxon. The moniker refers to the pirate's supposed ability to empty a four-litre (about 1 US gal) mug of beer in one gulp. At this time, pirates and other fugitives from the law often adopted a colorful nom de guerre.

Born in the Baltic port of Wismar, Störtebeker entered public consciousness around 1398, after the expulsion of the Victual Brothers from the Baltic island of Gotland, where they had set up a stronghold and headquarters in the town of Visby. During the following years, Störtebeker and some of his fellow captains (the most famous of whom were Gödeke Michels, Hennig Wichmann and Magister Wigbold) captured Hanseatic ships, irrespective of their origin.[3]

Störtebeker had a stronghold in Marienhafe, East Frisia, dating from about 1396. He married a daughter of the East Frisian chieftain Keno ten Broke (ca 1310–1376). A tower bearing his name (Störtebekerturm) still exists at the Evangelical Lutheran Marienkirche in Marienhafe.[4] [5]

Legend

According to legend, in 1401, a Hamburgian fleet led by Simon of Utrecht caught up with Störtebeker's force near Heligoland. According to some stories, Störtebeker's ship had been disabled by a traitor who cast molten lead into the links of the chain which controlled the ship's rudder. Störtebeker and his crew were captured and brought to Hamburg, where they were tried for piracy. Legend says that Störtebeker offered a chain of gold long enough to enclose the whole of Hamburg in exchange for his life and freedom. However, Störtebeker and all of his 73 companions were sentenced to death and were beheaded on the Grasbrook. The most famous legend of Störtebeker relates to the execution itself. Störtebeker is said to have asked the mayor of Hamburg to release as many of his companions as he could walk past after being beheaded. Following the granting of this request and the subsequent beheading, Störtebeker's body arose and walked past eleven of his men before the executioner tripped him with an outstretched foot. Nevertheless, the eleven men were executed along with the others. The senate of Hamburg asked the executioner if he was not tired after all this, but he replied he could easily execute the whole of the senate as well. For this, he himself was sentenced to death and executed by the youngest member of the senate.[6]

According to legend, when Störtebeker's ship was found, the masts contained a core of gold (one of gold, one of silver, and one of copper). This was used to create the tip of St. Catherine's church in Hamburg. His famous drinking cup was stored in the town hall of Hamburg, until it was destroyed in the great fire of 1842.[7]

Recent events have suggested it is more likely that Störtebeker and his crew died in 1400. A bill for digging graves for 30 Victual Brothers dated to this year survives in the Hamburg records. This would also suggest the story that Störtebeker was sentenced to death with 70 other privateers is at least misleading; at minimum, he certainly was buried with 30 other men. The year 1400 also excludes the involvement of Simon of Utrecht and the Brindled Cow (Bunte Kuh), since the records show this ship was not completed until 1401. In fact, the Hanseatic fleet that attacked Störtebeker was commanded by Hermann Langhe (also Lange) and Nikolaus Schoke (Nicoalus Schocke), who set sail for Heligoland in August 1400, and the course of the battle is not described by any reliable sources.[8]

Appearance

No authentic portrait of Störtebeker is known. An etching made by Fifteenth century German artist Daniel Hopfer, often erroneously identified as a portrait of Klaus Störtebeker, is actually of Kunz von der Rosen (1470–1519), court jester of Emperor Maximilian I. However, a tentative reconstruction of Störtebeker's appearance has been made using a skull alleged to be his. This skull, displayed at the museum since 1922, was stolen in January 2010.[9] In March 2011 it was found by the police.[10]

Memorials and legacy

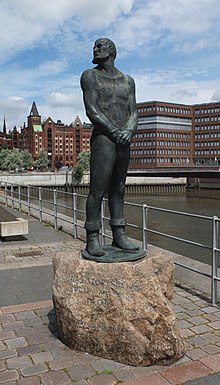

- Statues depicting him stand in a number of Northern German cities, including Hamburg, Verden an der Aller and Marienhafe.[11]

- Störtebeker Festival (Störtebeker Festspiele) is an open-air theatre event, held annually in the town of Ralswiek on the isle of Rügen.[12]

- The term Stoertebekerland has been adopted to promote tourism in East Frisia[13]

Novels and other popular culture

The character of Klaus Störtebeker has appeared in various recent publications including Die Vitalienbrüder: Ein Störtebeker Roman. a German language novel by Willi Bredel (Hinstorff Verlag, 1996, ISBN 978-3-356-00658-2)

Störtebeker was portrayed on television by Ken Duken in Störtebeker, a 2006 miniseries. He was also the subject of a 2007 documentary and of the feature-length movie 12 Paces Without a Head, in the making in 2008.[14][15]

The German brewery Störtebeker Braumanufaktur chose their name as a homage to Störtebeker.

Other sources

- Bents, Harm (2003) Störtebeker. Dichtung und Wahrheit (SKN Druck und Verlag Norden) ISBN 978-3-928327-69-5

- Lornsen, Boy (2005) Klaus Störtebeker (Carlsen Verlag GmbH) (2005) ISBN 978-3-551-35447-1

- Puhle, Matthias (1992) Die Vitalienbruder: Klaus Stortebeker und die Seeräuber der Hansezeit (Campus Verlag) ISBN 978-3-593-34525-3

- Püschel, Klaus; Wiechmann, Ralf; Bräuer, Günter, eds. (2003). Klaus Störtebeker: Ein Mythos wird entschlüsselt. München: Wilhelm Fink. ISBN 978-3-7705-3837-9.[16]

References

- Piraten in Norddeutschland (Birgit Bachmann und Stefan R. Müller) Archived 2013-02-10 at Archive.today

- Hamburger Abendblatt about research and an exhibition questioning the identity

- Die Vitalienbrüder, eine Freie Kompanie im Ostseeraum (kriegsreisende.de)

- Störtebekerturm (Störtebekerland)

- Turmmuseum im Störtebekerturm (Ostfriesland Tourismus)

- Klaus Störtebeker (stoertebekers-teestube.de)

- The big fire - Hamburg 1842 (ksfhh.de)

- Matthias Puhle (1994). Die Vitalienbrüder: Klaus Störtebeker und die Seeräuber der Hansezeit (in German) (2nd ed.). Frankfurt am Main: Campus Verlag. ISBN 978-3-593-34525-3.

- "Hamburg Searching for Plundered Pirate Skull". Spiegel Online International. January 21, 2010. Retrieved 2010-01-21.

- "Polizei stellt gestohlenen Störtebeker-Schädel sicher". Hamburger Abendblatt. March 17, 2011.

- "Das Störtebeker-Denkmal in Marienhafe (Touristinformation Brookmerland)". Archived from the original on 2016-03-24. Retrieved 2015-03-11.

- "Störtebeker Freilichtspiele (Touristinformation Brookmerland)". Archived from the original on 2017-09-14. Retrieved 2015-03-11.

- Stoertebekerland Official Website

- Störtebeker (moviepilot)

- Nicholas Kulish (November 6, 2008). "Germans revive a legendary pirate". NY Times.

- Herrmann, Bernd (2005). "Reviewed Work(s): Klaus Störtebeker. Ein Mythos wird entschlüsselt by R. Wiechmann, G.Bräuer and K. Püschel". Anthropologischer Anzeiger. 63 (2): 239. JSTOR 29542662.